An anonymous evaluation of the Dartmouth experience in relation to fifty years of living that followed it

The true history of a college consistsin the detailed and intimate experiencesof its students and the resulting changes intheir equipment for living. These experiences and changes are not adequately depicted by the list of a man's grades in theregistrar's office, nor by the list of his extracurricular achievements in the collegeannual.

Each individual is unique. No individual makes contacts with the whole college.He lives in a certain room, lie takes certain courses with certain professors, and,through more or less accidental contacts,he makes certain friends and shares in certain recreations. The sum of these contacts is different for each individual. Theeffect of these contacts varies with theheredity and previous experience of theindividual. The man himself does nothave a clear idea of the process as it goeson, since he is absorbed in momentary successes or failures that often have little importance in the long run. Perhaps theclearest picture emerges some decades later,when the man can see his college experience as a whole in relation to his latersuccesses and failures, and when his observation of other men's lives enables himto make comparisons.

What follows is one man's attempt totell what Dartmouth meant to him. Tothat extent, it is a tiny contribution to thehistory of the College.

WHEN I entered Dartmouth at the turn of the century, I had to go to the gym for a physical exam. One assistant took my measurements and called them off to another, who recorded them on a chart. "Neck eleven," said the measurer; "eleven," said the recorder. So they continued, making a permanent record of my meagre physique. At length they came to a space for "general muscular development."

"Slight?"

"We-el-l - "

"Call the chief!"

The chief was called. He approached with a bouncing stride, his muscles rippling through his gym suit. "Muscular development?" he said, glancing at my nude form. A shocked look crossed his face. "Zero!" he snapped, and strode away.

I had long known that I was physically inferior. A series of illnesses had robbed me of a normal boyhood. I never learned to play baseball or football. My boyhood home was in sight of a great river, but I never joined the muckers who dropped their clothes on the bank and learned to swim in the river. Since I was an only child, as well as a sickly one, it is not surprising that my parents over-protected me in various ways. Both my grandfathers were farmers, but I was never sent to spend the summer on either farm, or even left there for a few days without my parents. Summer camps were still unheard of. In fact I had never been separated from my parents for more than a couple of days at a time until I went to college.

My physical inferiority was a handicap in my relations with other boys. Unable to fight, I had to rely on passive resistance or flight. I sometimes tossed off a stinging sarcasm, but that only made matters worse. Since I did my lessons well and my teachers did not conceal their approval, I was branded as "teacher's pet." I became a natural butt tor bullies. The physical director's "Zero!" was only the most recent of the many insults I had endured. Still, I resented it, because I had ridden a bicycle quite a lot for four or five years, and I thought that at least my legs were not too bad.

I suppose many of my classmates were timid and lonely in the first weeks of our freshman year, but I am sure I was among the most timid and most lonely. A great majority had friends from their home towns in our class or among the upper-classmen. But I knew no one at all, because I had chosen Dartmouth instead of the urban college that was most popular in my home town. My health had been improving through my grammar school years, and during high school I was never absent because of anything worse than an ordinary cold. But my parents and I had got in the habit of regarding my health as a problem, and we felt that a country college would be better for me than a city college.

There was another thing that turned me towards Dartmouth - the beauty of the surrounding country. One summer my parents and I had spent two weeks in Bethlehem, New Hampshire, and I fell in love with the New England mountains. We enjoyed seeing and photographing the mountains from different distances and directions, under different conditions of noonday and evening light, of mist, cloud-shad-ows and sunshine.

Our most thrilling experience was the ascent of Mount Washington by the cog railway. "Chugga-chugga, chugga-chugga, chugga-chugga," went the engine. The air got colder and thinner, and the trees in the valley below looked smaller and smaller. When we reached the top, we scrambled about over the irregular rocks that cover the summit. Clouds were around us and below us. For the first time I fully realized that clouds are not wads of cotton, but merely fog at a high altitude. As the clouds shifted, gaps appeared between them, revealing bits of sunlit landscape far below and far away. We opened our box lunch and ate it in the damp and chilly air. Since then I have always associated the exhilaration of being on a mountain top with the odor of hard-boiled eggs.

I was not only without friends in the college when I entered but I was not adept at making friends. Dale Carnegie had not Yet written his classic on How to MakeFriends and Influence People, and if he had I would have been too shy to apply his methods. I was more at home in the classroom or with books than with people. I had some close friends in high school but was not a very good mixer. Once I was among eight finalists in a public speaking contest. A friend and I helped each other rehearse for it. I corrected many rough spots in his delivery, but it was he who won the prize. He had the competitive temperament that I lacked, and a warmth and forcefulness that I could not match. I was distressed by cuss-words and blushed at four-letter words. Of course I did not drink or smoke.

In spite o£ these handicaps and inhibitions, my boyhood had been a happy one. I was happy in my home. My parents were gentle but firm people. They over-protected me, but I do not think they spoiled me. My mother spanked me promptly when I needed it, and was never so weak as to say, "Just wait till your father comes home and he'll fix you." My father contributed to my education in many ways. His reports of his daily experiences gave me glimpses of the practical realities of business, law and politics. On Sunday after noon walks with him I developed an interest in birds that has lasted the rest of my life. My mother started me in music, and that also became a permanent interest. I took to books without urging. Irving's Alhambra introduced me to a magic world. When I was fourteen, a friend of my father gave me an anthology of English poetry, and I was entranced by Shelley's "Cloud and "Skylark." In my teens I developed an interest in architecture, and drew from the public library, one after another, a series of little volumes that described the cathedrals of England and the legends that cluster around them. I was happy in the classroom and liked almost everything that I was asked to learn. Being happy at home and in the classroom far outweighed the humiliations previously mentioned.

MANY things about the Dartmouth of my time would seem strange to undergraduates of more recent decades. There were no autos, no radios, no movies. There were no skis, no Outing Club, no Winter Carnival. There was no Selective Process. If you passed the entrance exams you were admitted, with no nonsense about personality, an alumnus father or geographical distribution. As we had never heard of Freud, we all considered ourselves reasonable beings, competent to manage our own lives, and none of us expected to land on an analyst's couch. There had been no big war for a long time, and none was expected. We had no thought that war could ever affect us personally. We all firmly expected to die in bed of natural causes. Since no one had a correct idea of what the twentieth century would be like, how could our elders be expected to prepare us for it?

Then, as now, athletics and fraternities dominated the college scene, and I was not prepared for a place in either. I was not even prepared to shine in such minor activities as dramatics, debating or the glee club. That I was well prepared for classroom work was not a social advantage. The captain of the football team stood at the apex of the social system, and the less you resembled a football captain, the lower your social status was. The gregarious and competitive spirit was dominant. How was an introvert like me to get along in such an extrovert college? I did not see my problem in those terms, as I had never heard of introversion or extroversion, and I knew next to nothing about Dartmouth or any other college. I looked forward to college with an awed but eager expectation of something, I knew not what.

I spent my freshman year in a private lodging house. In that way I escaped most of the horseplay and hazing to which freshmen were subjected. There were two sophomores in the house who made themselves disagreeable, especially by their talk about VD, but by the aid of passive resistance I survived their occasional perse-by two men who became my closest friends.

Tom and Dick had grow up together in a small town on the coast of Maine. Tom was short and stocky. His clear eyes were merry or serious as occasion warranted. He worked hard at his studies and at the jobs that helped him pay his tuition. In the summer he worked for his father, who was a boat-builder. When he relaxed he was completely relaxed, and I could always relax in his presence. He had no quarrel with the way the world is run, and had a quiet confidence that he could meet any problem that came along. Dick was the opposite of Tom in many ways. He was slender, agile and tireless in hiking or climbing. He was a lover of Thoreau and a hater of authority. He eagerly studied the things that suited his tastes, but he rebelled at uncongenial required courses. Being a rebel and a dreamer, he was less at ease in the world than Tom. They were alike, however, in their love of the woods and fields, and that was some of the things that drew me to them. One walk led to another, and our friendship grew.

My debt to a few close friends in high school and again in college is enormous. They kept me from drawing into my shell, and showed me how precious the friendly association with people more extroverted than myself could be.

After my year in a private house I spent the three remaining years in a dormitory. This enabled me to mingle freely and casually with a greater variety of students,, and the number of my friends gradually increased. I even became an officer in one of the departmental clubs, and sometimes, presided at meetings when other officers, were absent.

My chief social relaxation was of the most blameless sort imaginable. Already in my freshman year some friends had introduced me to a Sunday evening gathering at another lodging house. The landlady, her daughters, and five or six students enjoyed singing fine old hymns or popular songs like "Nita, Juanita and "I've been Workin' on the Railroad." I enjoyed the presence of girls in the group, but none of them ever made my heart skip a beat.

Kinsey was still in diapers or kilts, and even i£ he had been old enough to begin his inquiries he would not have learned much from me or my friends. The village of Hanover offered few temptations, as it consisted solely of families of the faculty and the tradesmen and boarding-house keepers who made money from the students. In general the daughters of the village were carefully supervised. Since temptations were scarce in Hanover, some of the more extreme extroverts went in search of them elsewhere. Standard procedure was for a group to hire a rig from the livery stable and drive five miles to a neighboring town for an evening of alcohol and sex. The horse could be trusted to find his way back to the stable, however drunk the driver. The horse and buggy age thus had at least one advantage over the age of autos.

Such expeditions were psychologically impossible for an introvert like me. I could no more have accepted an invitation to join one than I could have jumped from a third-story window. And I was never invited. Once, to be sure, a gang invaded my room at two or three a.m., after reeling into the dormitory on their return from such a foray. They teased me by telling me what a lot of good it would do me to join their next expedition, and hilariously described the situations they would thrust me into. But that was not a serious invitation, and they never mentioned it after they sobered up.

FOR many students the classroom, laboratory and library were necessary evils, but I sincerely liked most of my studies and was deeply enthusiastic about foreign languages and literatures. I found endless fascination in words and the ways of combining them, but I found the thoughts and feelings of great men revealed in their words still more absorbing. For me the study of literature was like ex- ploring a marvelous palace. Door after door was opened to me, and each chamber seemed more magnificent than the preceding one. To be sure, there was drudgery in acquiring vocabulary and syntax and historical backgrounds - as if one had to scrub the floor and dust the bric-a-brac before one could gaze in awe at the lofty windows, rich murals and coffered ceilings.

Some non-studious students suspected that any enthusiasm for study was either hypocritical or morbid. They understood and respected competition for dollars in business, or competition for a place on an athletic team. They imagined that their more studious classmates were also driven by competitive motives - perhaps to "make" Phi Beta Kappa - and they saw little value in such a goal. But in fact I saw little evidence of competitive spirit among my more studious classmates; in general those who made high grades worked be- cause they liked the subjects they studied.

Football was almost a religion. It had its rituals, its prayers, its hymns, its saints, its pilgrimages, its despairs and its ecstasies. I participated in all these, though not so fervently as the extreme extroverts, and they did me good. I enjoyed the rallies before games, when the yearning for victory was expressed in pep talks by coach, captain, and sports-minded professors. Cheers were rehearsed and football songs were sung. These occasions were like religious revivals, except that the faith inculcated was faith in the glory of football in general and the certainty of Dartmouth victory in particular. Defeat brought despair and victory brought ecstasy. Victory was celebrated by an immense bonfire, with processions, songs, cheers and speeches.

About ninety-five per cent of the students made the trip to Boston for the Harvard game, and I eagerly joined this annual pilgrimage. At the game we sang and cheered and felt the hopes or fears that came with each line plunge, end run or punt. Those games would seem comparatively dull today. They consisted mainly of slogging (sometimes slugging) through the line, since the forward pass was not yet thought of. But they were thrilling enough to us, since we had not seen anything more thrilling.

All this, I say, did me good. I shared the emotions of the crowd and felt myself a part of it. Vicariously I experienced the joys of combat, team-play and triumph which I could not achieve in my own person. I could not be an athlete or a fraternity man, but as a unit in the cheering, singing crowd I was as good as any other unit. In cheering, I made only a small noise, but I heard the roar of the crowd as if it came from my own lungs. Moreover, I was doing what was expected of me as a member of the College, while in the classroom or on hikes with one or two friends, I was following my individual bent. Football brought unrestrained expression of feeling and acceptable participation in the group - in that way it made me less introverted, more self-satisfied and happier.

LIKE many other adolescents, then and now, I was troubled about religion. The popular Protestantism in which I was brought up demanded that one pass through a definite series of emotions - first, a profound sense of guilt; second, repentance and yearning for forgiveness; third, the acceptance of Christian doctrine as currently taught; fourth, the surrender of private will to the Divine Will; fifth, the glorious feeling that one had been forgiven and accepted by God as a true Christian. In my early adolescence I had tried hard to achieve this sequence of emotions, but somehow I never succeeded. For a while I was deeply troubled by this failure, but by the time I entered college I had become accustomed to it. I felt that there was much that was sound in Christian tradition, but also much that I could not accept, and I was puzzled as to where to draw the line.

Daily chapel was a requirement at Dartmouth. There was a brief service each weekday at three minutes before eight, and a longer service on Sunday afternoons at five-thirty. President Tucker spoke at all of these services unless he was out of town. He was a fine figure of a man with aquiline features and keen blue eyes, a splendid speaking voice, alert bearing and springy step. The total impression was one of manly vigor, natural dignity and high intellectual powers. He rarely mentioned controversial dogmas. His steady emphasis was on personal integrity and devotion to worthy causes and institutions. I do not recall that he ever quoted Tennyson's line, "Self-reverence, self-knowledge, self-control, these three alone lead life to sovereign power," but his preaching was in harmony with that thought. When he gave a series of sermons on the Ten Commandments, he did not emphasize the thunders of Sinai, but showed how the commandments laid down conditions that were necessary for community living. His preaching built up in his hearers a solid conviction of the soundness of basic Hebrew-Christian moral ideals. President Tucker became my standard of what a really great man must be. Since that time I have seen and heard many prominent men, but each of them seemed to lack some element of greatness that he possessed.

In my quest for light on religious issues I attended a number o£ midweek meetings at the College Church, at which various professors set forth their religious views. But I was soon disgusted by the fact that they would often say, I like to think.... On such occasions I would leave the church muttering, "I don't give a blankety-blank what you like to think, I want to know what there is sufficient reason to think!" I was trying to purge my personal religion of wishful thinking.

Approaching religion from another angle, the love of nature which I shared with Tom and Dick was akin to the pantheistic tradition of Wordsworth and Emerson. We found both physical and spiritual refreshment in our country walks. We felt in harmony with nature when our eyes swept over a broad landscape, or when we examined trees or ferns or flowers. In the fall we delighted in the richly varied coloring of the wooded slopes. The deep greens of pines and hemlocks and the white trunks of birches provided contrasts to the reds and yellows of other trees. In winter the snow translated the landscape into new forms of beauty. Skis, as I said before, were not yet in use, but snowshoes enabled us, with a little practice, to get away from the highways rutted by sleighs. With snowshoes we were free to explore woods and fields, or even go up a mountain trail. In the spring the delicate greens of new foliage and the lively songs of birds created an exhilarating atmosphere. The exercise of walking and the companionship of friends enhanced all these experiences. If it is true piety to be at peace with ourselves and with things, we were truly pious!

Our greatest joy was to climb one or another of the mountains within reach of Hanover. Since there were no autos this involved a trip by rail to whatever station was nearest the mountain, and a hike of several miles along country roads to its base. Then we plunged into the woods, following a trail that led upward more or less steeply. There were pauses for breath on the steeper slopes. There were other pauses when an opening among the trees gave us a glimpse of the valley below or of some distant peak. Finally there came the exciting moment when we emerged above the tree line, and surveyed all the landscape that was not blocked off by the rocky summit itself. Then we hurried up the rough trail to the highest point, where we commanded the full circle of the horizon.

As the sun set, we enjoyed the changing forms and colors of the clouds, and the deepening shadows on the woods and fields below us. Then we made our supper from the provisions we had brought. We spent the night in a cabin, or wrapped in blankets under the stars. We were wakened early by the light of dawn and the singing of birds. We shivered as we watched for the sun to rise. At last its edge appeared; gradually but rapidly its whole disk was exposed. Then we turned quickly to the west, to see the shadow of the mountain, which at first reached clear to the horizon; we watched it gradually shorten as the sun rose higher and higher. We ate the remainder of our food, and made our way down the trail, conscious that each step brought us nearer to civilization, and the trivialities we had so gladly escaped.

WAS Dartmouth the right college for me? Should an introvert have gone to a college where extroversion was even more dominant than in most colleges? I must admit that the pressure toward extroversion produced some degree of strain. However, it was never enough to make me wish that I had gone somewhere else. I needed to become more extroverted than I was, and I wanted to do so. In my four years at Dartmouth I made a fair amount of progress in that direction. I did not become as competitive or gregarious as the average Dartmouth graduate, but it was not necessary that I should. The world has room for a wide range of temperaments, and one can earn a living, have friends and bring up a family without being as extroverted as the average man. I have never been discharged from a job; I have never been unemployed, except once for a couple of weeks. I have never been divorced, jailed, bankrupt or psychoanalyzed. My children have been able to earn a living, to get married and to present me with grandchildren. I remain more introvert than extrovert, since I still prefer books, music, family life, a few choice friends, and cooperative rather than competitive activity. I would not have it otherwise. Dartmouth helped me to move as far as was necessary toward extroversion. If I had gone to a college where there was less pressure toward conformity, I might have associated only with introverts, and so might have failed to develop a useful degree of extroversion - I might, or I might not.

On the intellectual and cultural side I might have developed more rapidly if I had gone to an urban university where graduate students mingled with under-graduates in the courses of junior and senior year, where a great library was ready to supply any book that might be needed for any by-path of inquiry, and where there was varied stimulation through plays, symphony concerts and art museums. But as an undergraduate I was kept busy learning things that I could learn without those advantages, and later experience in large cities filled some of the gaps. Nearly all the courses I took were well taught. Two of my teachers stood out above all the rest and became my personal friends. Elsewhere I might have found men more famous than these two, but I doubt that they would have done me more good.

When I think of my life at Dartmouth, I think of the progress I made from timidity and loneliness toward self-confidence and participation in community life; I think of my favorite studies and my favorite teachers; I think of President Tucker; I think of my friendships; I think of the woods and mountains; and I say to myself-

I am glad I went to Dartmouth. Iwouldn't have missed it for anything

A peerade to Boston at the turn of the century

"Those games consisted mainly of slogging through the line

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

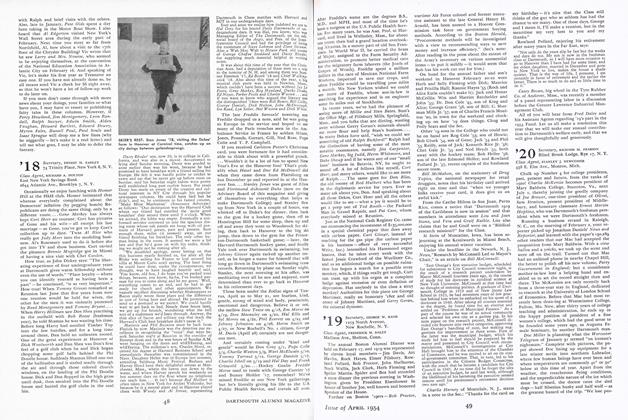

FeatureADMISSIONS—SCHOLARSHIPS—ENROLLMENT

April 1954 By Robert L. Allen '45 -

Article

ArticleThaddeus Stevens, 1814

April 1954 By JOHN S. MONAGAN '33 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

April 1954 By REGINALD B. MINER, WILLIAM H. PERRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

April 1954 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, MARVIN L. FREDERICK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

April 1954 By JOHN A. WRIGHT, BEN W. DREW