A casual tip about a one-dollar novel putthe author in distant orbit around some big(and listen, we're talking really big) stars.

I BOARDED THE WILDLY VEERING ROCKET that would bring me into Hollywood orbit into proximity with the supernovas, with the Brandon Tartikoffs and Michael Jacksons of the universe in a decidedly indeliberate way.

It was a gray December day in 1990 and I was browsing at the Strand "TEN MILES OF BOOKS!" just off Union Square in New York. I was looking over one of the trays of dollar books. I'm a journalist and get paid a journalist's wage.

I spotted a thin novel, Christmas at Fontaine's, by William Kotzwinkle. I knew something of this Kotzwinkle: long hair, cult following, sometime eroticist and, of all things, the "novelizer" of E.T., handpicked for the job by super-supernova Steven Spielberg himself, a big Kotzwinkle fan (of the clean stuff, I presume).

What the hell only a buck.

The novel was terrific, a page-turner about a bag woman and an obsessed department store window-display artist, trapped within a Macy's of sorts (Fontaine's) and within one another's sphere of influence at the Christmas season. Funny, surreal, spiritual and with a pretty happy ending, to boot. I loved it. I started sharing it around with friends.

"It's a 'Miracle on 34th Street' for the nineties," I told them. In our small circle, Christmas at Fontaine's became a famous book.

Enter Duke.

John N. Hart Jr. '75 was known to us to all of us in the class of '75 as Duke. He was the quintessential BMOC, and upon graduating he was our Wunderkind. While we others were hitchhiking and skiing and drafting resumes back in '76, Duke was somehow getting himself listed as an associate producer of Eubie!, the hit musical.

Now before we continue, let me say that I realize none of what Duke does is ephemeral or accidental. It's hard work, even if he works bicoastally and can use "lunch" as a verb. It's just that the farther you are away from a thing, the odder it looks. I've aways seen Duke's world from afar, and it's always seemed quite...illusory. Duke, at 22, could set us up with house seats to see Gregory Hines sing and dance. That's a conjurer's trick to us. But Duke worked very seriously to attain his magicianhood.

Anyway, back to the narrative: That December two years ago, Duke called and invited me and my friend Luci to his West Side apartment for a Christmas-season dinner. Over cocktails I learned that Duke's latest production company was interested not only in stage shows but in movies too. I said, "I just read this book and you should read it, Duke—it's wonderfully cinematic. It's a 'Miracle on 34th Street' for the nineties."

Duke said send it over. I figured he was being polite.

Two days later Duke called me at the office. In his stentorian voice, he said, "You're right! The bag lady! The human drama! You know what this is? A 'Miracle on 34th Street' for the nineties!"

Duke called a few days after that. He said apparently NBC owned the property as a potential TV movie but that it was in "turn-around." which apparently meant it was available. (I'm a journalist; beats me.) He said Kotzwinkle wanted to write the screenplay. Duke had doubts. Kotzwinkle's latest screenplay something that sounded vaguely bratpackish, as I remember was in release as a movie even then, and was a flopperoo. Duke figured Kotzwinkle could be bought off. It might take a couple hundred grand, Duke figured. I coughed.

Duke called again. He was just back from Hollywood and somehow had got his hands on Fontaine's. More than that: He had been riding in a limo (no fooling) with David Kirkpatrick, who was then the head of Paramount, and had pitched ideas at him. Kirkpatrick liked one of them, precisely one. Christmas at Fontaine's. Duke was entering into a production agreement with Paramount.

Let's do lunch, Duke said to me.

Luci and I were jogging around Washington Square Park in the spring of '91 when I told her the Kirkpatrick story. "You should write the screenplay," she said.

"Oh," I said, as if I'd never thought of that. "I've never written one."

"Well, I bet you could."

I pretended to be out of breath.

A very fancy, hard-cardboard invitation came in the mail. A brand new Broadway-based production company named Lerner-Hart-Hubbard was having its launch party at Mortimer's, and would Luci and I like to attend. It sounded like shrimp to us, and so we RSVP'd "Sure!"

We showed our hard cardboard to the big fella outside Mortimer's and made our way in, past some truly thin women and expensively dressed, long-haired, and suntanned men. It was not only shrimp but champagne, and a small jazz combo was playing as well. Duke spotted us as he was glad-handing. He told me that things with Fontaine's were zooming along, and that he had attached a screenwriter. (I'm going to leave the names of the screenwriters out of this, since they don't come off so hot. Trust me that each of them has a considerable track record of commercial success not only in Hollywood but on Broadway.) Duke said he was envisioning a "Garry Marshall-type movie" and that "Maybe we can get him when his new one ('Pretty Woman,' by the way) comes out." He said he'd just lunched with Kotzwinkle in Manhattan and that Kotzwinkle had taken some money and was happy. I figured: As well he might be, considering his novel was sucking dust in the dollar tray at the Strand a few months earlier. Duke said "Enjoy the shrimp" and "Let's have lunch." Which we would do.

Luci and I eased out of Mortimer's brushing past the superagent Swifty Lazar (as someone told us) on our way to the door.

Duke called about lunch. We met for sushi west off Times Square. Duke knew the sushi chef.

Duke told me the Fontaine's screenwriter was busily at work, and asked who I thought should direct. I said that with the book's oddball, even mystical nature, maybe a Bill Forsythe ("Local Hero") or perhaps a Fred Schepesi ("The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith"). I even mentioned Francis Ford Coppolla, and Duke thought this was an interesting idea. I said I thought the kid who was the brother of that woman the kid in "Say Anything," whose sister was a hoot in "Working Girl" would be right for the window-designer, and that Meryl Streep, that famous Greener-for-a-term, could reprise her "Ironweed" thing as the bag lady. "Yeah, she lives in town," said Duke, the wheels turning.

"Yeah, definitely," I said. "It has to be a New York movie. Maybe even Woody?" This was before all the Mia ugliness.

"But anyways," I continued. "The important thing is the screenplay. It'll be difficult to capture the magic of the book. The magic-realism. It needs to be deftly done."

Was I lobbying?

Oh, I couldn't have been. Someone was already "attached."

"I'm concerned about that," said Duke. "I was jogging around the reservoir with Name Witheld last week, and I'm not sure he's got it."

Duke sent over a big fat contract that I signed and sent back to Lerner-Hart-Hubbard. This was the Fontaine's contract with Paramount. I signed right under where "John C. Hart Jr., Producer" had signed. The gist seemed to be that I'd get a percentage of whatever percentage L.-H.-H. got from Paramount as a finder's fee. I thought this was a very nice thing for Duke to have done to send over this finder's fee agreement as he had.

Let's see...What happened next? Well, Kirkpatrick got canned in a famous shake-up at Paramount, and the famous Brandon Tartikoff, the latest mogul of moguls, took over. For a while.

Luci and I were jogging around Washington Square Park and she said, "Whatever happened to that movie Duke was making?"

"Well," I said. "It's interesting. I got a check last week, right out of the blue. Maybe Duke got an advance from Paramount. Or maybe a last payment, 'cause this guy Tartikoff just came in at Paramount and I'm sure he'll can a lot of the stuff that was in production, or pre-production, or whatever. Too bad. Would've made a good movie, it was very cinematic."

"That book could've been the 'Miracle on 32nd Street' for the nineties."

"34th," I said. "Anyways, it might have done okay. Look what that 'Home Alone' did."

I called Duke. He said a bunch of ideas had been thrown at Tartikoff from the hopper of ideas left over by Kirkpatrick, and that one he'd given the go-ahead to was Fontaine's. "But," Duke continued, "the screenplay was terrrrrrible! We've got a new guy working on a second one Name Witheld II."

"Oh," I said. "Hope it works out."

Duke called a little while later. He said "Brandon" wanted to turn it into a musical, and he said something about Michael Jackson playing the ghost. I can't remember if Jackson had been approached, or if it was just an idea. I had thought Jackson was owned body and soul by Sony, but then I figured Hepburn and Bogart and those folks used to be loaned around by the studios, so.. .What do I know?

In the spring of' 92 Duke was on TV holding up the front-page review in The New York Times of Guys and Dolls, of which Duke was one of the producers. He subsequently set up house seats for me and Luci; it is her all-time favorite musical, and she liked Duke's—well, the class of '67's Jerry Zaks's production even better than the very good one we saw in London a few years ago. I noticed in the G&D Playbill that Duke's production company something now called "Kardana" was not only involved with Guys and Dolls, but was producing the movie "Christmas at Fontaine's" for Paramount.

I called Duke, who said he was having doubts that the new Fontaine's screenwriter "got it." He said he was praying this guy would do a better job because Paramount would soon tire of paying these guys all of these $125,000 advances. I coughed.

In May my employer sent me for the rest of the year to Sydney, Australia, of all places. Who should call when I got there but...Duke! He said he was entering into a production agreement to stage Howto Succeed in Business (Without Really Trying) in Sydney, of all places. Apparently he'd gotten in tight with Frank Loesser's widow, Jo Sullivan, through the G&D thing, and therefore he had license to trot Loesser's other musicals around and there- fore... "Let's have dinner when I'm down there," Duke suggested.

We did, at Bennelong's at the Opera House. We talked about old times at Dartmouth, about mutual class o' '75 friends. Eventually, we got around to Fontaine's.

"I met with Brandon on my way down here," Duke said. "Nice guy, and he's still keen. But I really have doubts about Name Withheld II. He just doesn't get it. I'm sure of that now."

"Look, Duke," I said. "You get it, and I get it. It's Christmas, it's magical, mystical it's the cane-by-the-door at the end of 'Miracle on 34th Street.' It's Seussian. It's the Grinch.

"You and I get it, Duke, but... "Look, Duke," I said again. "If this script doesn't work out, I'll write it."

I was so ashamed. So embarrassed. I had just seen "The Player" the week before, and here I was, pitching a friend. I knew immediately what this was: Pitching a friend, is what it was.

Duke said, "You probably should've written it in the first place. Of course, Paramount wouldn't have gone for that. We'd never have gotten a deal."

"So what's its fate?"

"We'll wait till we see the screenplay."

"And, also, Duke you sure this should be a musical?"

"That wasn't my idea."

"I know, but..." I was looking down at my plate of very good sea trout. "And Michael Jackson?"

"He's no longer involved."

He was involved?

That night Duke and I attended The Crucible at the Opera House's Drama Theatre. It was pretty good, but pretty weird, too, with all these Australians doing Massachusetts Pilgrim accents, and only a couple of them getting it right. I grew up near Salem, and was perhaps overly critical. The production seemed too displaced, too foreign, too other-worldly. Sort of like Hollywood.

Duke called from New York. He wanted me to scout some theaters for him in Australia, venues that were "potentials" for HTSIB(WRT). This I did gladly, not only in Sydney but in Brisbane. I was wined and dined by Duke's Down Under partners, and given champagne at the interval of Grease, which was then playing in Brisbane. I was treated like a wheel, and I dug it.

Duke called again. He woke me up and quickly apologized for getting the time-of-day conversion wrong. He was all excited. Although I was in a haze, I grew excited too. Fontaine's, I thought. I'm gonna write it! Brandon loved the idea of this no-name guy being "attached"!

Duke said he'd just returned from a party celebrating the cast album of The King and I with Julie Andrews and Ben Kingsley, and that's why he was excited. I said, "Oh." He said that his new Sydney partners had produced TKAI Down Under with Hayley Mills, and that it was this production that had provided the framework for the recording. He said it had been great, talking to "Julie." He said also that Kardana was involved in bringing Tommy east from L.A., and I said that'd be a hit for sure. I told him I had read about it in Time International. I immediately started thinking about house seats. Duke gave me the dates he would be next in Sydney, and said we had to do lunch or dinner.

"Anything on Fontaine's?" I asked at last. "Oh," said Duke. "Well, the screenplay just didn't work, but I've sent it along to Brandon anyway, with a note telling him it didn't really work, but that here it is."

"Oh," I said. "Where's that leave it?"

"Well," said Duke. "I figure they'll put it in turnaround."

What comes around turns around.

Just a few days after that call, I noticed in The Australian that the legendary and all-powerful Brandon Tartikoff had "unexpectedly resigned" at Paramount. A couple of days after that I read that Sherry Lansing had been named chairman mogul of moguls of the company's Motion Picture Group. I thought about calling Duke to find out what it all meant, but I figured that whatever it all might mean now, it might mean something else tomorrow and a third thing the day after that.

I flew home for the Christmas '92 holiday shortly after that phone conversation. I read two books on the flight, books I had brought down just in case I needed to get to work on a screenplay. There was Fontaine's, of course. And Miracle on 34th Street. I figure I was just finishing one, just beginning the other, as the plane flew over the Hollywood Hills.

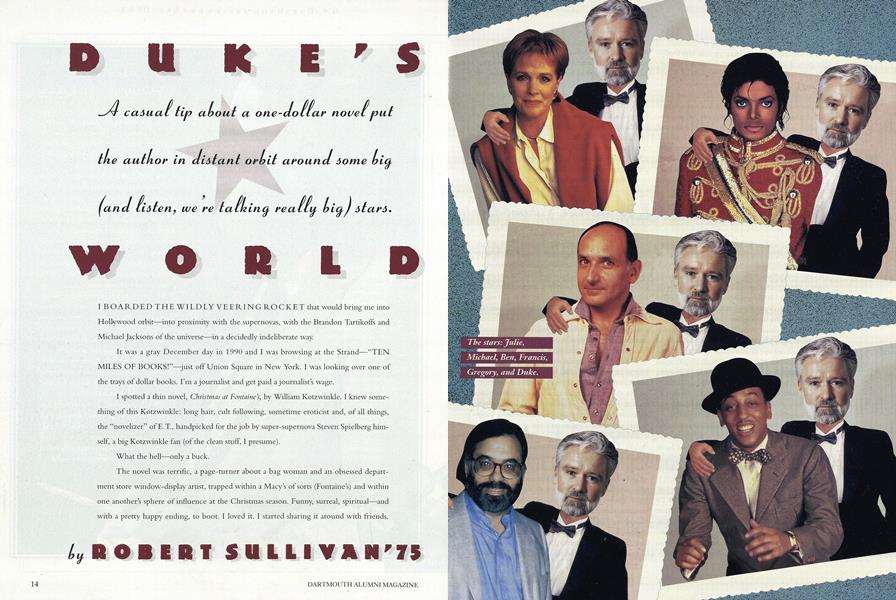

The stars: Julie, Michael, Ben, Francis, Gregory, and Duke.

The musical that almost wasis now in "turn-around."

I'VE ALWAYS SEEN Duke's world from afar, and it's always seemed ... illusory.

HE COULD BE bought off. It might take acouple hundred grand, Duke figured. I coughed.

ROBERT SULLIVAN is the editor of Sports IllustratedAustralia. He remains, screenplay-wise, unattached.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFor The Sake Of Argument

February 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureRoller Screaming

February 1993 By John Morton -

Feature

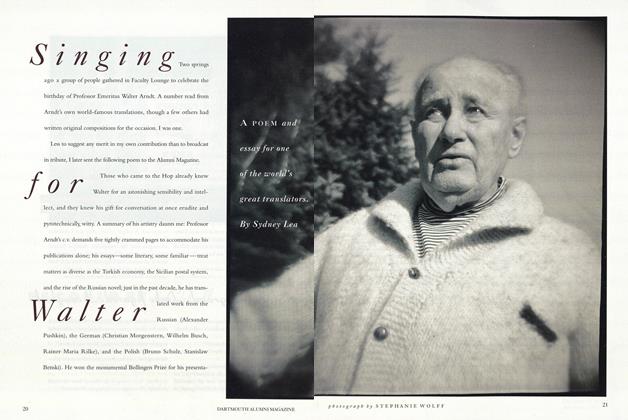

FeatureSinging for Walter

February 1993 By Sydney Lea -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleImagining the Orient

February 1993 By Douglas Haynes -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

February 1993 By Kenneth M. Johnson

ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

MAY 1986 -

Sports

SportsFifty-one Minutes

May 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

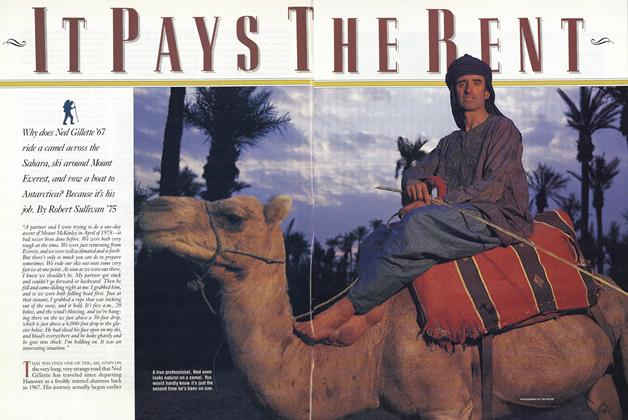

Cover Story

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

APRIL 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Murder Mystery Mystery

June 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Off-Broadway

SEPTEMBER 1997 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureOld School New School

March 1998 By Robert Sullivan '75

Features

-

Features

FeaturesIn the Face of Depression

MAY | JUNE 2025 By CHRIS QUIRK -

Feature

FeatureGreat Britton

Mar/Apr 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureWHO OWNS DARTMOUTH?

FEBRUARY 1991 By Joe Boldt '32 -

Feature

FeatureBuilding for Today—and 1969

February 1951 By PROF. JOHN P. AMSDEN '20 -

Feature

FeatureVerdict on the Dartmouth Institute: A-OK

OCTOBER 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureThe View from Oxford

NOVEMBER 1971 By Sanford B. Ferguson '70