Edited by Albert Virgil House '27. Columbia University Press, 1954. 329 pp. $4.75.

It was the good fortune of Professor House to discover and purchase some years ago the Journal and Account Book of Hugh Fraser Grant of Elizafield Plantation, Georgia - Elizafield being a rice plantation on the Altamaha River not far distant from the Butler plantation made famous by Fanny Kemble. The discovery was of real importance as the Journal and Account Book are unusually complete for the years 1834-1861, and thus present in great detail the financial, agricultural and marketing problems and operations of the ante-bellum Georgia rice planter. It is not surprising that the Columbia Studies in the History of American Agriculture found the Journal, together with a number of excellent introductory chapters by the editor, a valuable addition to its studies.

In his preliminary chapters the editor lays the foundation for a ready understanding of the Journal and Account Book by first introducing the reader to the history of Elizafield and its owners, the Grant family. The techniques of rice culture in Georgia are then discussed, leaving the reader convinced that rice culture in the Old South was as scientifically planned and carried out as any form of agriculture in the nation prior to the Civil War. In a chapter devoted to finance, supply and management practices, the capitalistic nature of the southern plantation system is brought out, together with the planter's sources of capital and credit, the role of the factor in the plantation economy, and various problems of plantation management and operation, including the organization of the labor force. The final chapter deals with the harvesting, threshing and milling of the rice and with the complexities of marketing the staple.

The Journal itself gives the reader an almost day to day record over many years of Hugh Fraser Grant's activities as a planter. The entries are brief, but a careful reading is rewarding as, year after year, the Journal carries the reader through the annual round of plantation activities. Here is, indeed, a mine of information for the agricultural economist and historian, but for the general reader, unfortunately, there is relatively little of the personal element in the Journal, nor does the journalist have much to say about his labor force which he seems to have referred to always as "the People" or "the Negroes" but never as slaves.

In the Account Book of the plantation we have a remarkably full record of Grant's dealings with his factors, and with the many business houses which he drew on for his supplies both for the plantation and the family. In identifying these last Professor House has done an astonishingly complete bit of research.

The record closes with a group of miscellaneous items such as the names of the slaves, crop summaries, accounts with overseers, relatives and neighbors, tax returns and plantation remedies. Of the coming of the Civil War with its problems for the rice coast, there is nothing beyond a final entry dated "Waresboro, Ware County 1861 Oct. 26, Moved my family & part of the Negroes here out of the way of the Vandal Yankees.

Professor House has done a first rate job both in his introductory chapters and in the editing of the Journal and Account Book. The research which is indicated is impressive. Certainly students of American agricultural history have good reason to be grateful to him.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePresident Emeritus Hopkins Is Honored With Dartmouth's First Alumni Award

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureRobert S. Oelman '31 Heads Alumni Council for 1954-55

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureE. S. French Retires as Life Trustee; Ruml Succeeds Him

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureAnother Record for the Fund

July 1954 -

Class Notes

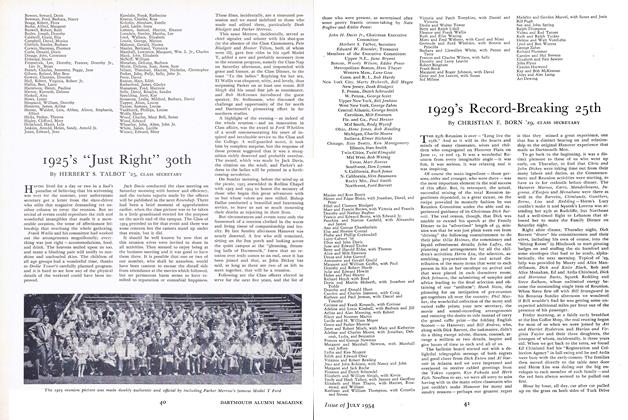

Class Notes1929's Record-Breaking 25th

July 1954 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN '29, BILL ANDRES, SQUEEK. -

Article

ArticleThe 1954 Commencement

July 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON

W. RANDALL WATERMAN

Books

-

Books

BooksCOME SPRING

June 1940 -

Books

BooksGREAT MEN & WOMEN OF POLAND

February 1942 -

Books

BooksA Survey of State Forestry

November 1946 -

Books

BooksTHE ILIAD OF HOMER

March 1952 By Philip Wheelright -

Books

BooksNotes on a Yale man's journal and the 'elbowing self-conceit of youth.'

MARCH 1978 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksANTS WILL NOT EAT YOUR FINGERS A SELECTION OF TRADITIONAL AFRICAN POEMS.

JULY 1969 By RICHARD D. TAYLOR