THE pressure exerted by the mass media of communication in America today is to make us all alike. We are all treated the same in the expectation that we will respond with sameness. Yet the deepest pressure that we inherit from our cultural past is the urge to be different, to shun sameness like a plague and to cherish and assert our singularity. This is the paradox of our contemporary culture, and its predicament.

As a teacher of literature I happen to believe that any nation's literature is a trustworthy indication of that nation's character. American literature, I think, is especially revealing. Our serious and lasting books, the ones that last because they do validly express aspects of our experience and have thus become a part of that experience, are significant documents, although that is surely neither their only nor their chief value. Our novels, for example, stand as novels first, and their documentary usefulness is secondary. But before one generalizes too vastly about America one had better read them.

So let us turn to our fiction and try it for findings. The major fiction of the nineteenth century in this country begins, I suppose, with Cooper and Poe, the Leatherstocking Tales and the Poe short stories. Then there are The Scarlet Letter, TheHouse of the Seven Gables, Moby Dick,Huckleberry Finn, The Ambassadors, TheRise of Silas Lapham, The Red Badge ofCourage, and we are already past the turn of the century. Our roll call is probably too brief and partial, but it will serve as a list of some of our serious novels. These are all books which come out of our life as a people and which strike back into it. They are the books we will give our children to read to learn about our past, provided, that is, our children can spare the time from the television screen to read at all. These are the stories we remember with a sense of ownership - and owning up to. And as documents they are full of meaning.

Calling the roll of their titles is hardly enough. Let me call, too, the roll of their protagonists, their heroes and heroines, the people who move centrally in their pages. There is Natty Bumpo, first of all, the deerslayer and the pathfinder, shunning settlement and striking, in book after book, off into the wilderness. Then comes Poe's strange and haunted hero, a single figure although he appears under various names in various stories. He, too, is a pathfinder, but the wilderness he explores is the unknown land of nightmare and subjective terror. There is Hester Prynne, the branded adulteress, who works out her hard salvation in a kind of ultimate loneliness. There are the Pyncheons, Hepzibah and Clifford, withdrawing back into the shades of their gloomy house after one futile adventure in flight. Then comes Ahab, the mad skipper of the Pequod, pursuing the deadly white whale far into the China seas. Huck Finn floats down the big river, himself a runaway, with a runaway slave as his companion. Lambert Strether, fastidious and bewildered, journeys to Paris for his initiation into a world that is foreign to all he has known. Silas Lapham, no less an initiate, has come from the farm into a treacherous new region of tricky commerce and high society, but he has not come to stay. And Henry Fleming, deserter, scampers like a frightened animal from the fury of Chancellorsville.

These are our heroes and heroines. An oddly unheroic lot, one may observe. What significant patterns of character or conduct do they share?

I BELIEVE they share one pattern in that they are all centrifugal. They distrust the center and in every case their characteristic movement is away from it. All, either literally or figuratively, go on a journey. It may be a search, a chase, a flight, an embassy, a quest, or a foray. Whatever it is, its effect is to cut loose and to isolate. It is always a striking away, never a settling down; always a moving off, never a digging in. Invariably it elects singularity over plurality.

This centrifugal pattern is not peculiar to the novels I have chosen to examine. Other stories would suit the demonstration as well, and our poetry would reveal the same pattern as our fiction. Indeed, it is here that our imaginative experience most closely matches our historical experience, for in our history, too, in Newton Arvin's words, "dispersion, not convergence, has been the American process." In his Hawthorne, Arvin asks, "What have been our grand national types of personality?" He answers his own question with an eloquent catalogue:

The explorer, with his face turned toward the unknown; the adventurous colonist; the Protestant sectarian, determined to worship his own God even in the wilderness; the Baptist, the Quaker, the Methodist; the freebooter and the smuggler; the colonial revolutionary; the pioneer, with his chronic defections; the sectional patriot and the secessionist; the come-outer, the claim-jumper, the Mormon, the founder of communities; the Transcen-dentalist, preaching the gospel of self-reliance; the philosophical anarchist in his hut in the woods; the economic individualist and the captain of industry; the go-getter, the tax dodger, the bootlegger....

Had he been writing today, Arvin might have added the atomic scientist and the juvenile delinquent.

Obviously the animating force behind these figures is morally ambiguous. It can produce splendid individuals or embittered eccentrics, bold leaders or cranks and criminals. But, good or bad, these national types share an aversion to centrality and to the sameness that centrality entails. They are in revolt against and in flight from uniformity, and it is for all of them that Emerson, another figure one had better not neglect when generalizing about America, is the spokesman.

Is it not the chief disgrace in the world, not to be an unit; - not to be reckoned one character; - not to yield that peculiar fruit which each man was created to bear, but to be reckoned in the gross, in the hundred, or the thousand, of the party, the section, to which we belong; and our opinion predicted geographically, as the north, or the south? Not so, brothers and friends - please God, ours shall not be so.

That was in 1837 when those words rang out. How goes it in 1955? Predicting our opinions has become a lucrative industry, and we are reckoned in the millions. Our radios and newspapers, movies and television sets, politicians and advertisers all unite, day after day, in a single insistent claim - that we matter not as individuals but only as members of a group. We are an audience, - televiewers, listeners, readers, or subscribers. We are a market, - consumers of Ballantine Beer or Camel cigarettes or Books of the Month. We are Republicans or Democrats, city dwellers or suburbanites, drivers or pedestrians. We are voters, college graduates, wage earners, possible security risks, or potential casualties, while our children are pressed into a vast amorphous mass of pliant adorers of Davy Crockett. Emerson's "chief disgrace in the world" threatens to become the normal condition of American man.

But his "Not so!" still carries conviction and may be prophetic after all. In spite of the constant promptings of the mass media, in spite of electronics and newsprint, I doubt if we can, overnight, outgrow our centrifugal past and forget our heritage of singularity. Is it not more likely that, before long, the impulse that has been bred into us may reassert itself? Then, perhaps, we may answer all the skilled manipulators of the masses, not with uniform acquiescence, but with some such words as these: Gentlemen, you have been mistaking us. We are Americans, long accustomed to be counted one by one. We are not identical and we are not merely plural. So leave us, if you please, alone.

PROFESSOR FINCH at the request of the editors has put into written form the informal talk he gave during the 1930 Hanover Holiday discussions in June. He spoke on "The American Way of Life" as part of a panel on "Toward a Better Democracy." One of his English courses is devoted to American fiction before 1900.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

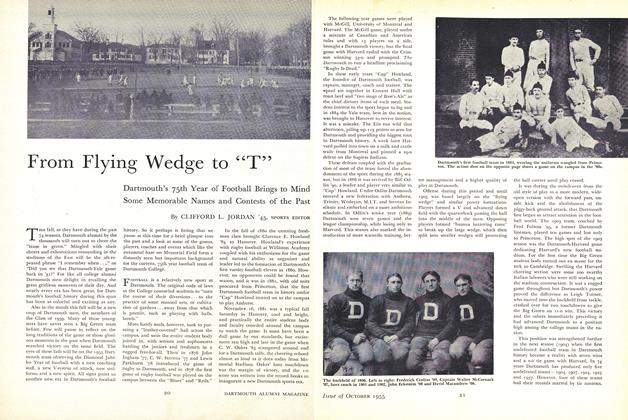

FeatureFrom Flying Wedge to "T"

October 1955 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45, SPORTS EDITOR -

Feature

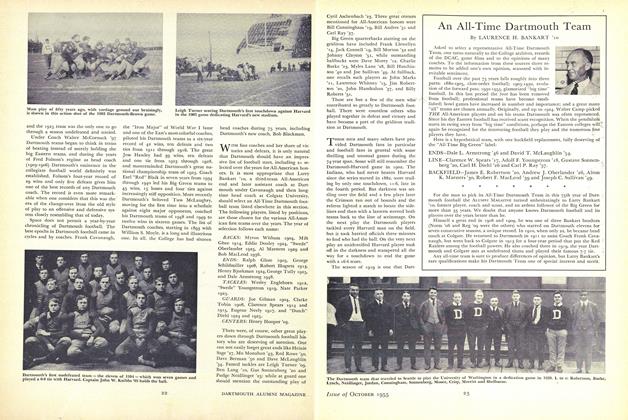

FeatureAn All-Time Dartmouth Team

October 1955 By LAURENCE H. BANKART '10 -

Feature

Feature'59 GETS STARTED

October 1955 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVFR, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

October 1955 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

October 1955 By HAROLD L. BOND '42

Features

-

Feature

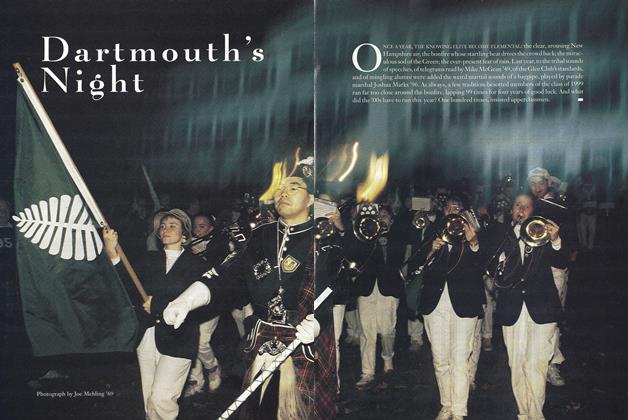

FeatureDartmouth's Night

OCTOBER 1996 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySEALED FILES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

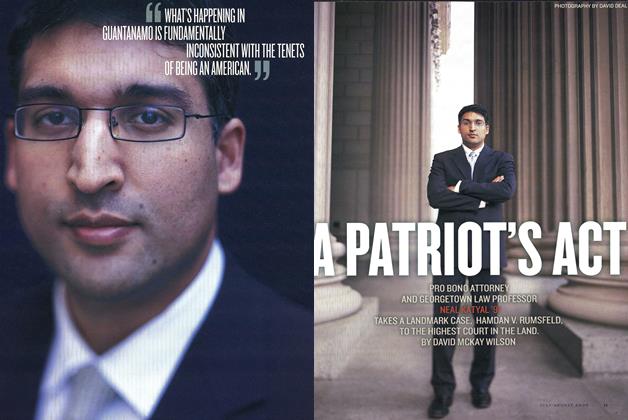

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July/August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Cover Story

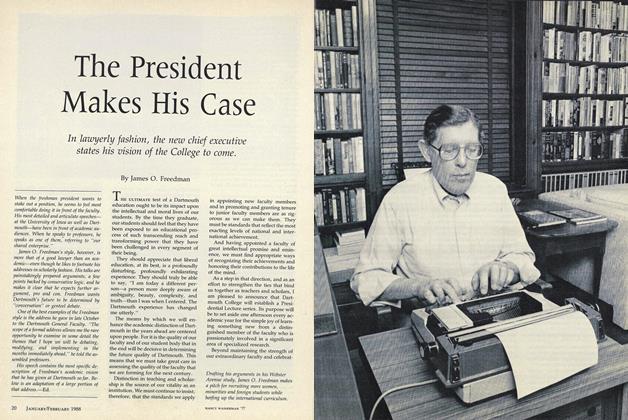

Cover StoryThe President Makes His Case

FEBRUARY • 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeaturePersonal History

May/June 2010 By JOE BABCOCK ’08 -

Feature

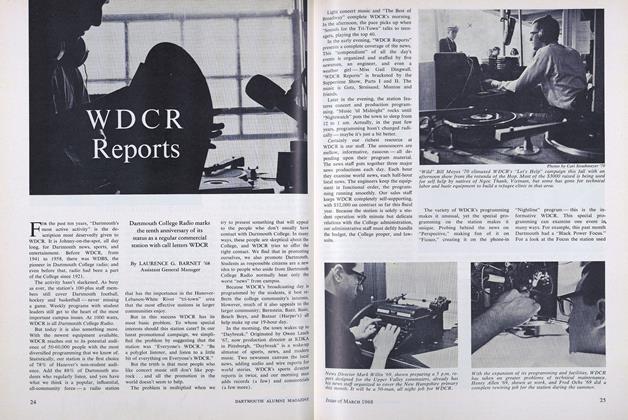

FeatureWDCR Reports

MARCH 1968 By LAURENCE G. BARNET '68