This book attests the irony of American democracy. On the one hand, Tom McIntyre rose to become the ranking Dartmouth alumnus in public life, a fact, incidentally, not always fully appreciated in this college community. Together with Hugh Bownes, now a federal appellate court judge, and Bernard Boutin, former General Services Administrator, McIntyre was one of a trio of Laconia men who attained high station in postwar America. Surely it should renew pride in our system that it continues to discover and use the talents of men of commonplace origins.

On the other hand, we now realize that in 1978, just when McIntyre's national influence peaked — at the very moment when his seniority on the Senate Armed Services Committee made him a rallying point for younger arms-control champions such as John Culver, Gary Hart, and Pat Leahy — the good citizens of New Hampshire saw fit to replace him in Washington by a reactionary airline pilot with no discernible qualification for responsible public office. I have always felt a bit uncomfortable about President Carter's plea for a government as good as its people. My suspicion is that in Tom McIntyre the people of the Granite State got a better leader than they deserved.

That he was replaced by a vintage "fear broker" gives this volume a relevance even greater than McIntyre had anticipated. Its thesis is that the "fear brokers" constitute a New Right which is stridently absolutist, indeed apocalyptic, in its opposition to such policies as arms control, gun control, birth control, and pollution control. As different from classical conservatism as the Union League Club is from the John Birch Society, the New Right is described as suspicious of corporate business, especially large multinational corporations, hostile to Establishment values, and above all quick to challenge the morality and patriotism of all who dare to disagree with it over Panama, busing, abortion, capital punishment, SALT, amnesty, marijuana, or "welfare cheaters." Part I of the book describes its leaders and tactics at the national level; Part II zeroes in on New Hampshire.

All this is routine stuff. Interest quickens when the author, with an assist from his gifted press aide John Obert, relates today's New Right to earlier groups such as the anti-Masons, the Know-Nothings, and the Klu Klux Klan. Following the American historian Richard Hofstadter, McIntyre traces the paranoid style of the followers of William Loeb or Meldrim Thomson to status anxiety. This is said to be found both in small town WASPs who see their world coming apart at the seams, and in upwardly mobile urban ethnics, often first- generation immigrants, who seek reassurance in idolatrous nationalism and religious fundamentalism.

The book goes on to argue that the New Right introduces divisive issues into a Democratic Party once united on New Deal bread-and-butter programs. The party splits into two factions, one symbolized by Jane Fonda and George McGovern, the other by Archie Bunker and George Meany. The latter cannot accept the attitude of the former toward race relations, foreign relations, or sexual relations, and the truth soon emerges that the New Right has a lot of political clout. It is a popular phenomenon; its roots — and here I carry the argument a step further than McIntyre does — rest in the frailties of ordinary human nature.

Because I have long watched public figures struggle with what we now term "social issues," the high point of this book for me is McIntyre's account of his changing personal attitudes. In a passage moving for its honesty, he concedes that it may have been "the unconscious defensiveness" of being new-family Irish Catholic "that made me waffle at first on McCarthyism ... that kept me too long a hawk on Vietnam; that early on persuaded me to 'err on the side of caution' in the Armed Services Committee by voting for weapons systems I suspected might be wasteful, unnecessary, or provocative...."

But the heartwarming fact is that McIntyre grows. Morally and intellectually he grows in the larger national arena. This is clear not only from his evolving policy posture, but in the respect he develops for such broad-gauged colleagues as Hubert Humphrey, Philip Hart, and Mark Hatfield, all mentioned prominently in this book. In a different but still commendable way, he celebrates his continuing friendship with that stalwart conservative Republican, Norris Cotton. During his tenure in government, McIntyre was no narrow politician. Thoughtful, public-spirited, and moderate, he danced to no man's tune. That was the basis of his reputation in Washington. One prays that it was not the reason for his defeat in New Hampshire.

THE FEAR BROKERSby Thomas J. McIntyre '37Pilgrim Press, 1979. 350 pp. $9.95

A former chairman of the New HampshireDemocratic Party, Professor Radway, chairmanof Dartmouth's Government Department,is a. close, if not entirely disinterested, observerof the state and national political scene.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureUncle Sam and Mother Dartmouth

November 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureIt's Where We're Coming From, Citizens

November 1979 By Jeffrey Hart -

Feature

Feature'A need for someone who holds my views'

November 1979 By William M. Hill -

Article

ArticleSeeker of the Heroic

November 1979 By Beth Baron '80 -

Article

ArticleGadfly

November 1979 By M.B.R -

Article

ArticleA Little More Anarchy, Please

November 1979 By Bruce Ducker '60

Laurence I. Radway

-

Books

BooksTHE POLITICS OF DISTRIBUTION.

June 1956 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksFREEDOM OF SPEECH BY RADIO AND TELEVISION.

APRIL 1959 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksFOREIGN AID AND AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY: A DOCUMENTARY ANALYSIS.

JANUARY 1967 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksMAN INCORPORATE, THE INDIVIDUAL AND HIS WORK IN AN ORGANIZED SOCIETY.

November 1968 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Feature

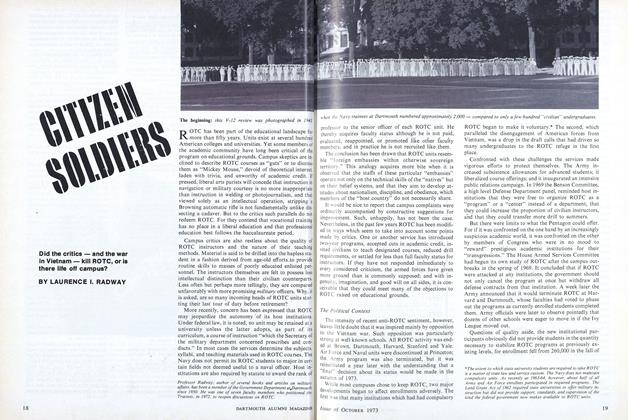

FeatureCITIZEN SOLDIERS

October 1973 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Books

BooksNot in the Stars

January 1976 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY

Books

-

Books

BooksMINUTEMEN AND MARINERS, True Tales of New England.

APRIL 1964 By CHARLES E. BREED '51 -

Books

BooksTHREAD OF SCARLET

May 1939 By E. P. Kelly '06 -

Books

BooksTHE HAND IN THE PICTURE,

November 1947 By Eric P., THEODORE KARWOSKI -

Books

BooksTHE NORMAL CEREBRAL ANGIOGRAM,

January 1952 By HENRY L. HEYL, M.D -

Books

BooksNotes on a humanizing craft, a National Book Award, the Adamses, Avant-garde dancers, Irving Howe's tribute, and the Texas nation.

June 1976 By R.H.R. -

Books

BooksCOLLECTIVE BARGAINING FOR PUBLIC EMPLOYEES.

MAY 1970 By ROBERT M. MACDONALD