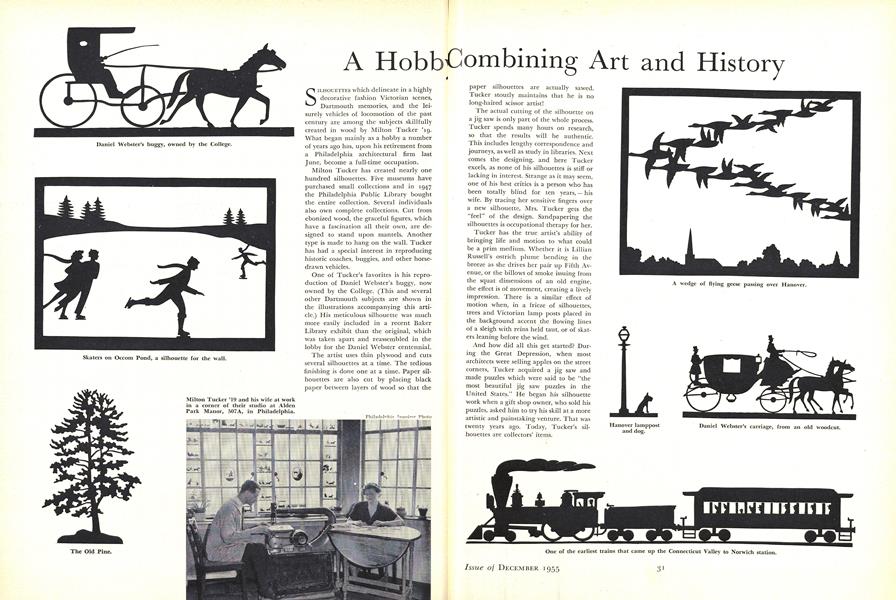

SILHOUETTES which delineate in a highly decorative fashion Victorian scenes, Dartmouth memories, and the lei- surely vehicles of locomotion of the past century are among the subjects skillfully created in wood by Milton Tucker '19. What began mainly as a hobby a number of years ago has, upon his retirement from a Philadelphia architectural firm last June, become a full-time occupation.

Milton Tucker has created nearly one hundred silhouettes. Five museums have purchased small collections and in 1947 the Philadelphia Public Library bought the entire collection. Several individuals also own complete collections. Cut from ebonized wood, the graceful figures, which have a fascination all. their own, are designed to stand upon mantels. Another type is made to hang on the wall. Tucker has had a special interest in reproducing historic coaches, buggies, and other horsedrawn vehicles.

One of Tucker's favorites is his reproduction of Daniel Webster's buggy, now owned by the College. (This and several other Dartmouth subjects are shown in the illustrations accompanying this article.) His meticulous silhouette was much more easily included in a recent Baker Library exhibit than the original, which was taken apart and reassembled in the lobby for the Daniel Webster centennial.

The artist uses thin plywood and cuts several silhouettes at a time. The tedious finishing is done one at a time. Paper silhouettes are also cut by placing black paper between layers of wood so that the paper silhouettes are actually sawed. Tucker stoutly maintains that he is no long-haired scissor artist!

The actual cutting of the silhouette on a jig saw is only part of the whole process. Tucker spends many hours on research, so that the results will be authentic. This includes lengthy correspondence and journeys, as well as study in libraries. Next comes the designing, and here Tucker excels, as none of his silhouettes is stiff or lacking in interest. Strange as it may seem, one of his best critics is a person who has been totally blind for ten years, - his wife. By tracing her sensitive fingers over a new silhouette, Mrs. Tucker gets the "feel" of the design. Sandpapering the silhouettes is occupational therapy for her.

Tucker has the true artist's ability of bringing life and motion to what could be a prim medium. Whether it is Lillian Russell's ostrich plume bending in the breeze as she drives her pair up Fifth Avenue, or the billows of smoke issuing from the squat dimensions of an old engine, the effect is of movement, creating a lively impression. There is a similar effect of motion when, in a frieze of silhouettes, trees and Victorian lamp posts placed in the background accent the flowing lines of a sleigh with reins held taut, or of skaters leaning before the wind.

And how did all this get started? During the Great Depression, when most architects were selling apples on the street corners, Tucker acquired a jig saw and made puzzles which were said to be "the most beautiful jig saw puzzles in the United State:;." He began his silhouette work when a gift shop owner, who sold his puzzles, asked him to try his skill at a more artistic and painstaking venture. That was twenty years ago. Today, Tucker's silhouettes are collectors' items.

Daniel Webster's buggy, owned by the College.

Skaters on Occom Pond, a silhouette for the wall.

The Old Pine.

Milton Tucker '19 and his wife at work in a corner of their studio at Alden Park Manor, 507A, in Philadelphia.

A wedge of flying geese passing over Hanover.

Hanover lamppost and dog.

Daniel Webster's carriage, from an old woodcut.

One of the earliest trains that came up the Connecticut Valley to Norwich station.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of a Liberal Education

December 1955 By PROF. ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Feature

FeatureA Course of Reading for Dartmouth Men

December 1955 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

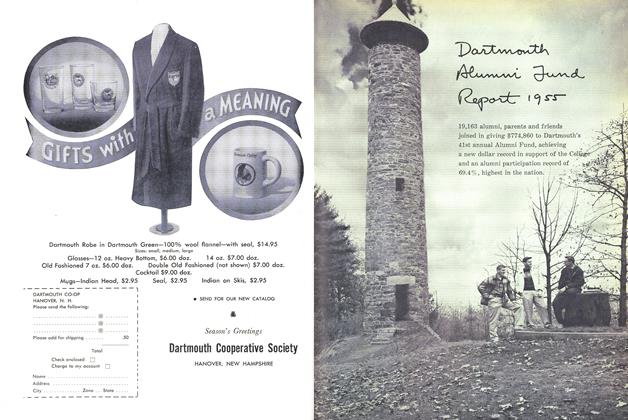

FeatureChairman's Report THE 1955 ALUMNI FUND

December 1955 By Roger C. Wilde '21 -

Feature

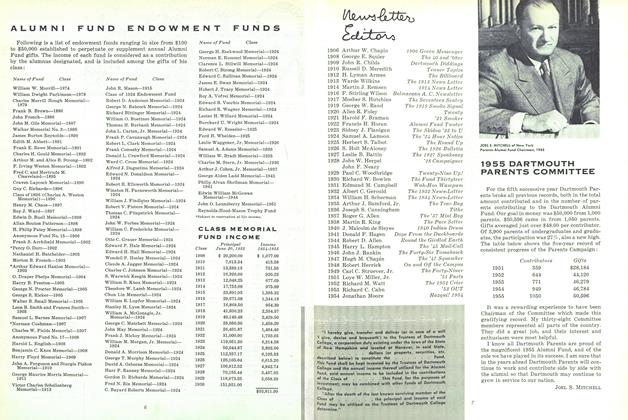

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

December 1955 -

Feature

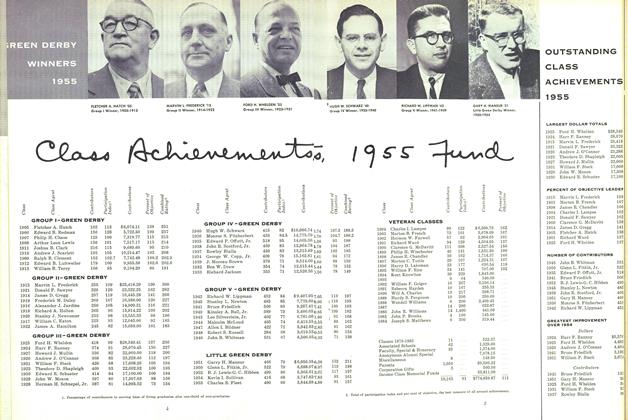

FeatureChass Achierement 1955 Fund

December 1955 -

Feature

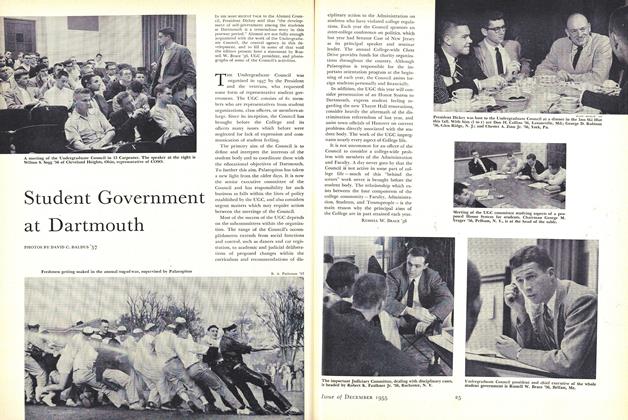

FeatureStudent Government at Dartmouth

December 1955 By RUSSELL W. BRACE '56

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryHorace Fletcher 1870

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

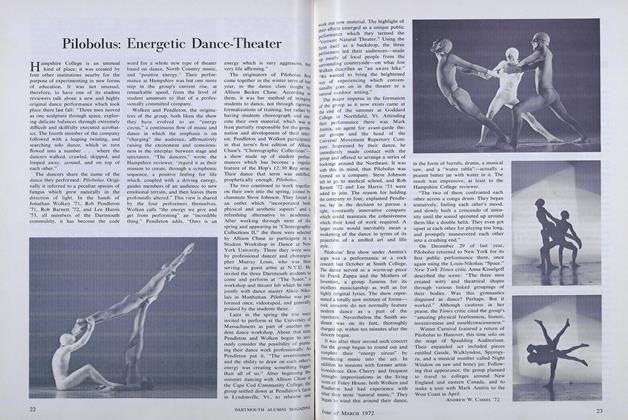

FeaturePilobolus: Energetic Dance-Theater

MARCH 1972 By ANDREW W. CASSEL '72 -

Feature

FeaturePostwar Change in Dartmouth's Educational Program

APRIL 1966 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureThe Life of the Mind

May 1955 By DR. ALAN GREGG -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

JULY 1959 By JOHN E. BALDWIN '59 -

Feature

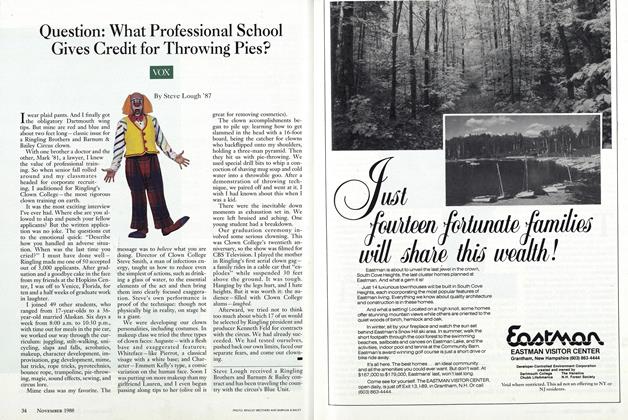

FeatureQuestion: What Professional School Gives Credit for Throwing Pies?

NOVEMBER 1988 By Steve Lough '87