WHEN William Jewett Tucker closed the door of his office July 15, 1909, and retired from the position of President of Dartmouth College which he had so completely filled for sixteen years (1893-1909), he tells us that he went to his home "in much freedom of mind and with a certain exhilaration of spirit." This freedom and exhilaration were possible because Dr. Tucker so clearly and finely conceived what "retirement" ought to mean to a man. He did not think of it as retirement at all. To him it was a "new reservation of time."

Let Dr. Tucker speak:

It is evident that a new principle has been set at work in the social order. Society is fast becoming reorganized around the principles of a definite allotment of time to the individual for the fulfillment of his part in the ordinary tasks and employments. The termination of his period of associated labor has been fixed within the decade which falls between his "three-score" and his "three-score and ten" years. The intention of society in trying to bring about this uniform, and, as it will prove to be in most cases, reduced, allotment of time for the ordinary life-work of the individual, is twofold. ... The first intention is evidently to secure the greatest efficiency, in some employments the best quality of work, in others the largest amount. ... The second, if not equally plain intention of society is to make some adequate provision in time for the individual worker before he becomes a spent force. It therefore creates for him a reservation of time sufficient for his more personal uses. Within this new region of personal freedom he may enter upon any pursuits, or engage in any activities required by his personal necessities or prompted by newly awakened ambitions.

I am not concerned with the results which society seeks to gain in carrying out its first intention. I think that the intention lies within the ethics of business, and that the results to be gained may be expected to warrant the proposed allotment of time. But what of the second intention of society? How far is it likely to be realized? What will be the effect of the scheme upon those now entering, and upon those who may hereafter enter, on the reservation of time provided for them? What is to be their habit of mind, their disposition, toward the reserved years which have heretofore been reckoned simply as the years of age? Will this change in the ordering of the individual life intensify the reproach of age, or remove it? Will the exceptional worker in the ranks of manual or intellectual labor, but especially the latter, who feels that he is by no means a spent force, accept reluctantly the provision made for him, as if closing his lifework prematurely, or will he accept it hopefully, as if opening a new field for his unspent energies? And as for the average worker, to whom the change will doubtless bring a sense of relief, will he enter upon the new "estate" aimlessly, or "reverently, discreetly, advisedly, soberly," and withal in good temper and cheer? (Page 417 of My Generation. Also the first pages of The New Reservation of Time.)

Read the last chapter of his autobiography My Generation for a delightful description of how Dr. Tucker spent his own "reservation." You can see there how fully he illustrated the principles described in the paragraph just quoted. Our present concern is with one signal part of this illustration, that out of this period came four books with which those who would understand the Dartmouth of today in its spirit and ideals ought to be quite familiar.

The first is Public Mindedness. The subtitle of this is An Aspect of CitizenshipConsidered in Various Addresses GivenWhile President of Dartmouth College. It was prepared for publication almost immediately after Dr. Tucker began his retirement, the preface being dated December 15, 1909. The first of the 24 chapters is entitled "Good Citizenship is Based on Good Citizens." The last is entitled "A Study of Contemporary Greatness." Between are chapters on education, economics, patriotism, and history, showing the wide range of Dr. Tucker's interests and his capacity to say something suggestive and unique with regard to them all. Particularly notable for the alumni are Chapter VIII, The Origin of the Dartmouth College Case, and Chapter XVI, The Historic College: Its Place in Our Educational System (his inaugural address, June 26, 1893).

The quality of these addresses will be suggested by the closing paragraph on page 356:

I deprecate the merely critical attitude of the schools, or of educated men, toward contemporary greatness. Criticism, if it is intelligent and honest, is wholesome to those who give and to those who receive, but its office at best is secondary. The thoughtful man should be sympathetic, appreciative, discerning. A great man, despite his faults, is the greatest possession of an age, next to a principle or a truth. Through him one interprets the collective life of his time; through him he reads the history of the age. Through him he gets his proper approach to human nature. The great danger which besets us in our estimation of human nature is that of indifference or of contempt. The average man may not interest us. But if we are to do with men in the way of utilizing or controlling them, we must know them; and the first condition of knowledge is interest, then respect, then faith. I have tried to show you what seems to me to be the true way into our common humanity. The greater man, whom we can know, honor, and trust, not the lesser man, whom we have not yet learned to know and measure, should be our guide.

The second book is Personal Power:Counsels to College Men, published early in 1910. This will be particularly interesting to the men of Dr. Tucker's day because it consists of addresses which they heard at Sunday Vespers in Rollins Chapel, and will be helpful to men of a later day in lieu of hearing them. It was in great degree these Sunday evening addresses which made so profound an impression upon the students of that day that many men now living will echo what an outstanding graduate has said of the influence of Dr. Tucker: "That influence was the supremely stimulating experience of my undergraduate life and has continued into my subsequent years." Sample subjects: Provisional Self-Government, Moral Maturity, The Satisfactions of Life in the Midst of Its Contradictions. There are also four addresses at the opening of successive college years 1905-1908 on The Moral Training of the College Man: The Training of the Gentleman, the Scholar, the Citizen, the Altruist. A quotation from the end of the address last named:

I would not have you underestimate the amount of motive which it takes to accomplish a college course, and to put you into right relation to an honorable career. Hence the question which I ask you, which I do not propose to answer, the most sobering and the most exhilarating question which men in your circumstances can entertain, each man for himself - Is my motive, my "governing idea," big enough and staunch enough to carry me through college? Is it true enough, brave enough, and sufficiently satisfying, to enable me to meet hereafter the temptations of men and the tests of the world?

The third book takes its title from the first chapter: The New Reservation ofTime. It was published in 1916 and consists mainly of articles which had appeared in the Atlantic Monthly between August 1910 and April 1916. It reveals Dr. Tucker as not only assembling what he had said and written previously but as also alert to contemporary events which were leading up to the First World War. The zest with which he reacted to this time is expressed in this extract from the preface to My Generation.

The closing period to which I have referred under the title, "The New Reservation of Time," represents, in the changed conditions of modern life, a new but most valuable perquisite of age. It has been to me, in its extent at least, an unexpected gift, reaching now to a decade, and enhanced in value beyond all estimate by the events which have crowded the later years. To have lived in such a period, to have shared in its grave anxieties and mighty hopes, to have been able to study into the causes which were producing such momentous sacrifices and struggles, and to have been allowed to witness the final consummation, all this has made the period of retirement more significant, even within the sphere of personal expression, than any preceding period of responsible activity. It has not been, I trust, inconsistent either with previous activities, or with the natural restraints consequent upon official retirement, that I have ventured from time to time, under the stimulus of passing events, into the open field of the publicist. (Page xi.)

The first chapter, which contains the quotation with which this article began, is a comprehensive statement of Dr. Tucker's philosophy regarding the meaning, the opportunity and the satisfaction of the years following relief from the details of administrative responsibility. All the chapters illustrate Dr. Tucker's intriguing distinction between the "essay" and the "article." The direct object of the article, he says,

is some immediate effect upon public opinion. In this immediateness of purpose it differs essentially from the essay. It differs also in regard to the variety of means through which it may seek to produce the requisite effect. It may be strictly informing, it may be argumentative, it may pursue its end with moral urgency. In all of which respects the article has close resemblance to public address, and opens the way, for one accustomed to this form of expression, to the use under proper restraints of the written page. (Page ix.)

The last chapter, "On the Control of Modern Civilization," was apparently not elsewhere published. How apposite this chapter is to our contemporary situation may be illustrated:

I believe that the time is at hand for the larger assertion of the spiritual life, meaning thereby the life of faith. All that can be asked of civilization at this point is room, a sufficient expansion to include the results of spiritual development. All else must come through the pressure of the spiritual life itself. But this will be sufficient. It is wonderful how the spirit of man gains its ground when it is quickened and enlarged to its normal capacity. Is it too much to expect that faith, as expressing the aspirations and demands of the human spirit, is yet to acquire a firmer footing and larger holdings, amid the crowded and resisting forces of a material civilization? Rather is it not unbelievable that a generation which has been brought face to face with the everlasting realities, and held so long in their presence, should allow itself to remain the easy subject, or the passive instrument, of an uncontrolled civilization? (Page 190.)

Appended to the book proper is Dr. Tucker's Phi Beta Kappa address at Harvard in 1892: "The New Movement of Humanity - From Liberty to Unity." Here again is remarkable contemporary significance for us today.

And now finally, and most revealing, is Dr. Tucker's autobiography published in 1919 under the title, My Generation: AnAutobiographical Interpretation. It is dedicated to two of his closest associates: Robert Archey Woods, during the Andover period; and Ernest Martin Hopkins, during the Dartmouth period. (It will be recalled that Mr. Hopkins, who graduated in 1901, became Dr. Tucker's personal secretary immediately after graduation and after four years in that position became Secretary of the College, a position which he held five years.)

Alumni will perhaps, naturally, turn first to the ninth and longest chapter of the book, entitled "The Dartmouth Period." But the first part of My Generation gives the background of the last part. Dr. Tucker had done a very notable work before he came to Dartmouth, though he did his greatest work here. His contribution while at Andover Theological Seminary to the establishment of freedom in American theological thinking and to the development, as a major interest of the Christian Church, of what has come to be known as the Social Gospel was of farreaching significance.

Parenthetically it may be noted that Dr. Tucker's professional life developed progressively in that he spent twelve years in the pastorate (in Manchester, N. H., and New York City), fourteen years as a teacher in Andover Theological Seminary and sixteen years at Dartmouth. Then came about eleven years when he carried out his new reservation of time, after which he was confined to his room and his bed and lived under the very close restrictions imposed by his doctor until September 1926. His malady was called, "a tired heart."

With the reading of the part of MyGeneration dealing with Dartmouth ought to go the reading of Leon B. Richardson's chapter in his History of Dartmouth College entitled, "The Administration of President Tucker." It is an absorbing and masterly account of a wholly successful administration.

Once, to this writer's personal knowledge, when Dr. Tucker was being congratulated upon his significant work at Dartmouth he made the characteristically modest and whimsical reply: "Well, a man ought to be able to do something with the Dartmouth Spirit behind him." But this Dartmouth Spirit was essentially his creation. It was latent before he came. He evoked it, clarified it, embodied it, and so made it pervasive and controlling.

Well has it been said that "the spirit of great creations never dies." Confidence in the future of Dartmouth College lies largely in the belief that on Hanover Plain and wherever in the country and the world there are Dartmouth men, the truth of this saying will again be revealed in the continuing influence of William Jewett Tucker.

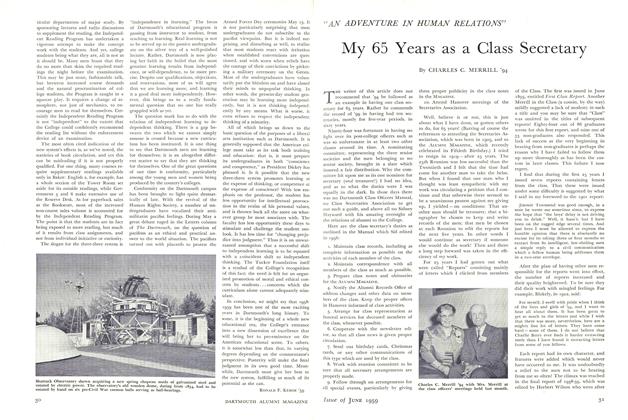

Dr. Tucker at his Hanover home after he hadretired as President of the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of a Liberal Education

December 1955 By PROF. ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report THE 1955 ALUMNI FUND

December 1955 By Roger C. Wilde '21 -

Feature

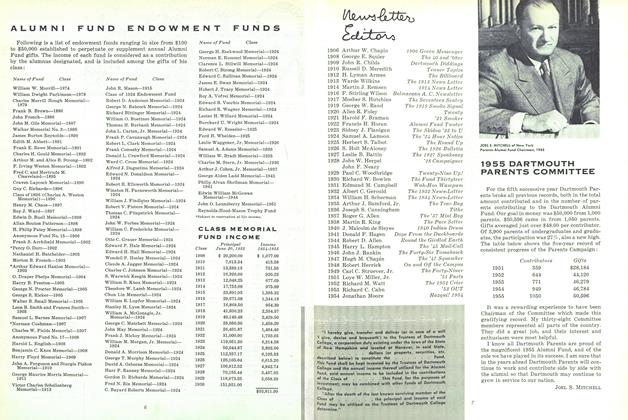

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

December 1955 -

Feature

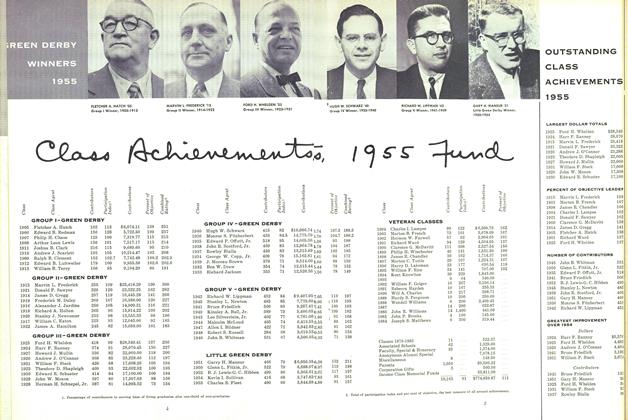

FeatureChass Achierement 1955 Fund

December 1955 -

Feature

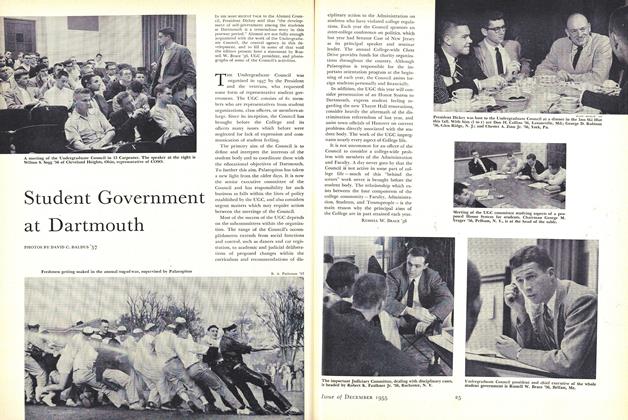

FeatureStudent Government at Dartmouth

December 1955 By RUSSELL W. BRACE '56 -

Feature

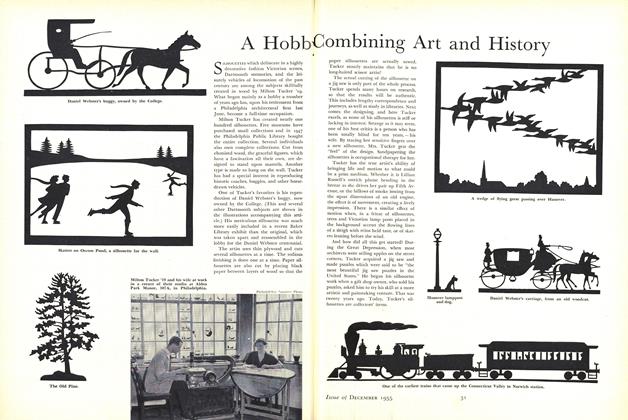

FeatureA Hobby Combining Art and History

December 1955

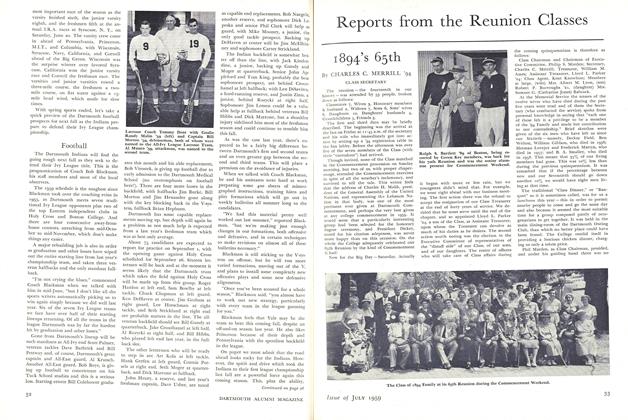

CHARLES C. MERRILL '94

Features

-

Feature

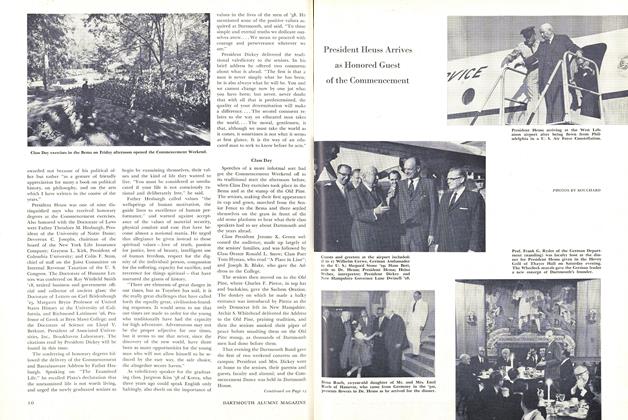

FeaturePresident Heuss Arrives as Honored Guest of the Commencement

July 1958 -

Feature

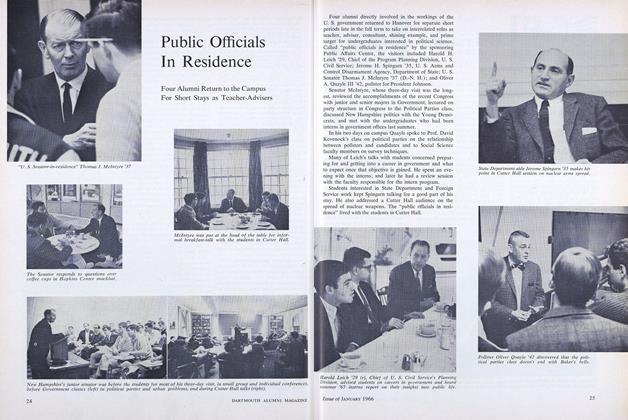

FeaturePublic Officials In Residence

JANUARY 1966 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1968 -

Feature

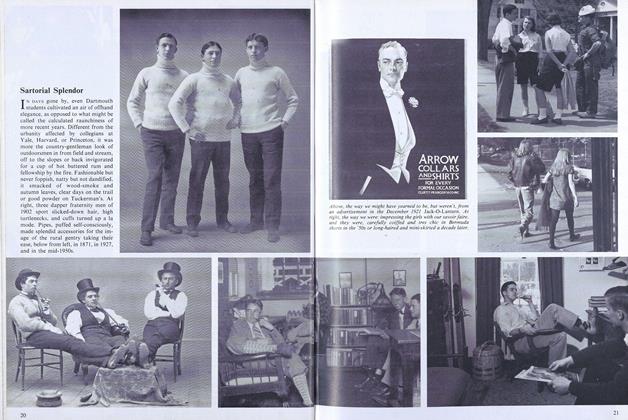

FeatureSartorial Splendor

December 1976 -

Feature

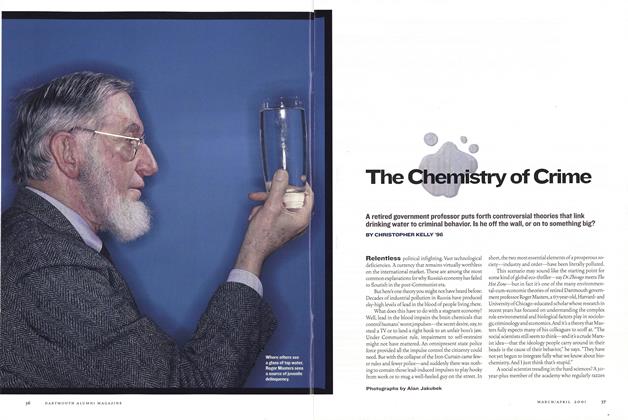

FeatureThe Chemistry of Crime

Mar/Apr 2001 By CHRISTOPHER KELLY ’96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHoney, They're HOME

January 1996 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79