OPPORTUNITY to supplement the classroom aspects of education often comes to Hanover in the form of lecturers, concerts, and the like, but rarely does the Dartmouth curriculum provide for taking students to the actual subject being studied.

However, this latter approach is employed regularly by Prof. H. Gordon Skilling in his government course on "International Organization." Dealing with the development of inter- and supranational organization, the course concentrates on the culmination of man's efforts in this field, the United Nations. And with the headquarters of the U.N. only a few hours from Hanover, an established feature of the course is a one-day tour through the magnificent structure on the shore of the East River in New York City.

"I feel," says Professor Skilling, "that the only way that students can get a vivid impression of the United Nations is by observing it in operation and meeting some of the key spokesmen of countries in the United Nations. At least a brief trip of this kind seems to me to bring home some of the great difficulties in the U.N. as well as some of its possibilities."

This fall the class, comprising ten men, all seniors or juniors, visited the U.N. on Wednesday, November 24. The day began at 9 a.m. with a standard guided tour which took the group into the beautifully decorated meeting chambers of the General Assembly, Security Council and Trusteeship Council. Visits were then made to several committee meetings, one, the Ad Hoc Political Committee, holding forth in another special chamber, that of the Economic and Social Council. In this session the committee was discussing West Irian, or West New Guinea, and the class listened in on a statement by the Australian representative. Palestine refugees in the Near East, technical assistance, and women's rights were dealt with in other committee meetings which the class visited briefly.

In these sessions the first of many known aspects of the United Nations began to come alive. The most elementary problem, that of communication, is handled by simultaneous translation and is no problem at all, and though classwork had made the group well aware of this fact, it was necessary to actually observe the process to fully appreciate its effectiveness. Another difficulty in traditional inter-state relations has been eliminated in the United Nations, for there is no question of how to bring nations together to discuss common problems. In every committee, again even though the situation was known to the class previously, it was a stirring experience merely to observe the give-and-take of international discussion. Through this process, despite parliamentary snarls and adamant stands, solutions are slowly ground out, and the machinery for securing agreement is always operating. Here the students observed the world bound together, and saw diplomats acquiring the ulcers which Warren Austin prefers over combat deaths.

To complete its morning session, the group spent an hour around a table with Benjamin Cohen, then Assistant Secretary General in charge of the Public Information Department and now head of the Trusteeship Department with the same rank. A Chilean, Mr. Cohen has been with the U.N. since its founding, and he outlined the place of the organization in world affairs and the progress it has made in nine years, a topic which is essentially the purpose of Professor Skilling's course.

In his brief, informal talk and the discussion that followed, Mr. Cohen spoke from his position of an "international civil servant." The class had previously found that this role requires subduing national allegiance to concentrate on the United Nations and the problems it and the entire world are facing, and Mr. Cohen fulfilled his obligations perfectly. Never did he label an individual nation the cause of trouble or show preference for policies of one state over those of another, but viewed existing difficulties as world problems to be solved through the growing concept of the world community.

After a brief noontime break, spent partly in browsing through the U.N. bookstore, the class met with Mr. V. K. Krishna Menon, head of the Indian delegation. Although visibly fatigued from his activity of the preceding few days in the General Assembly's atomic energy control debates, the articulate Indian was patient and very helpful in answering the group's questions. He denied that India is attempting to act as mediator between East and West, or that it is the leader of a third force in world politics. The Security Council veto, failure to agree on contributions to the U.N. armed force, and other disagree- ments are not the world's primary difficulties, asserted Mr.' Krishna Menon. Rather these are only manifestations of the basic misunderstandings and antagonisms which are today's real problems. At several points in the session, he expressed dissatisfaction with U.S. press coverage of the U.N. and world affairs in general, claiming that statements unfavorable to this country are always presented in a derogatory fashion or else obscured.

The last visit of the day was with Mr. Vilko Vinterhalter, head of the Yugoslav Information Center in New York. Though not a delegate, Mr. Vinterhalter, a wartime Partisan, professional journalist, and onetime economics professor, presented his country's viewpoints very adequately. He told the class about Yugoslavia's internal situation, claiming that true communism was succeeding in his country while Russia had reverted from its professed ideology to "state capitalism." His devotion to communism was sincere, as was his feeling of Yugoslavia's importance in the world, especially, he said, in bringing about, through defection from the Cominform, the Soviet Union's recent changes in foreign policy. Yugoslavia believes now that it can deal with the Soviets, he declared, but Tito will never return to the Russian orbit.

In both interviews, although many of the opinions expressed were not new, the class was impressed by the deep belief in them and by their soundness when presented by their proponents. As Professor Skilling states, "The most valuable experience we have had is meeting with the national delegations, because there you get a picture of the depth of national differences which must be overcome." At the

same time, "you get a conception of the United Nations as a living organism that has become a force itself, influencing these national positions."

Observing the everyday routine of an international community as it worked to iron out differences brought classroom work into viable perspective, and clearly indicated that Mr. Cohen's "world community," already in operation in embryonic form, embodies our greatest hope for peace among mankind.

A meeting of the Political Committee of the General Assembly

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePublic Interest an The Technological Revolution

February 1955 By LLOYD V. BERKNER -

Feature

FeatureMan's Aggressive Nature

February 1955 By GEORGE E. GARDNER '25 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

February 1955 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES JR., TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

February 1955 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleThe Underĝraduate Chair

February 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55

JOSEPH D. MATHEWSON '55

Article

-

Article

ArticleKEEPING UP WITH THE COLLEGE

December, 1915 -

Article

Article17th Century Chair Is Given to College

June 1954 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Trustee Nominated

February 1974 -

Article

ArticleBook Awards Program Brings College to High Schools

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 -

Article

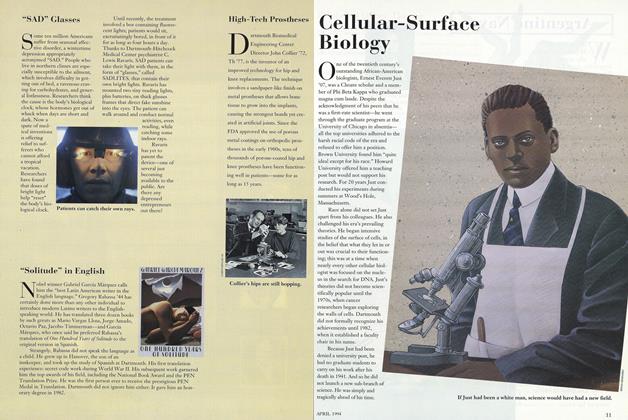

ArticleHigh-Tech Prostheses

APRIL 1994 -

Article

ArticleA Professor's Delights

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott