I HAVE been asked to speak to you about the aggressive impulses in man. There are two emphases to this lecture of mine; the first is on the origins and nature of aggressive behavior, which will carry us into the field of childhood, and secondly I would like to speak briefly on some mental health tasks that have at least tangible relationship to this topic we are considering.

My fundamental thesis or theme is that all human beings, in fact all living tissue is basically aggressive in its behavior toward its environment - the environment of things or the environment of people. It is through aggressive-destructive acts (in the sense of seizing and devouring) that we are able to sustain ourselves—through food taking—and once the food is within us we can utilize it for heat production, repair, and growth, only through "destroying" the ingested substances through imposed chemical changes. Our sensory and motor systems have been developed to enable us better to accomplish this aggressive attack on our potential food supply beyond ourselves. Thus is exhibited for us a very fundamental, cogent and instructive biological pattern of behavior that enables us to understand a lot of the behavior of human beings, though the element of aggressiveness or destructiveness in it may be covered up and seemingly absent.

So we maintain, first of all, that the child is aggressive and destructive by natural endowment. This aggressive behavior is inevitable because we are born with such tendencies. And I want to make even a better case for it by asserting that if it isn't always good, it is basically and in the long run present and active in the service of our very best interests. For what kind of a world would we have if we had no aggressive impulses at all? It seems to me that everything within and without us as individuals or as groups of individuals would be very comfortable but nothing whatsoever would be taking place. We would have internal and external peace but we would probably have nothing else. If we took away the impulse to destroy, to possess, to be aggressively curious, to explore in the face of frustration and obstacles, to master the physical environment around us, I am sure that we not only would have curiously uninteresting, uninformed and uninformative people; we probably would have no people at all. This is a difficult notion for us to accept, particularly difficult to accept at your age and development, and just after we have been subjected in this world to a series of hideous demonstrations of these aggressive impulses in war. But unfortunately I think my thesis is correct.

This initial consideration of both the good and the bad aspects of the aggressive impulse, whether seen in the light of individual behavior or group behavior or the behavior of nations, impels us to try to make, if we can, a differentiation between that type of aggression exhibited by children which we can reasonably and morally denounce as harmful and un- wanted, and that type of aggression in all of us that we can sensibly and even enthusiastically endorse. What is the basis of differentiation that can be made?

The most fruitful and provocative differentiation that we can make as regards aggressive behavior, I believe, is to note that although initially the child's aggressive behavior is destructive both in type and in aim, and has the destruction or elimination of something or somebody as its object, under our influence, i.e., under the influence of the external environment, the destructive aspects of aggression can be minimized, and the constructive results of the activity can be brought to the fore. That great, natural biological reservoir of aggressive energy that we all have because of our very makeup cannot be drained off and lost, nor can it be dammed up so that it can give no expression whatsoever. But the great bulk, and we hope all, of it can be deflected or diverted to channels that will demonstrate the individual's mastery or control of himself, and which in turn will be an expression of his mastery (in the good sense of the word mastery) and his control of the world about him.

It is the accomplishment of just this diversion and canalization of the aggressive destructive impulses that seems to me to be the foremost task in development, and in the ordering of our adult lives. There may be other developmental tasks that are important, but this one, the control of aggression, seems to me to overshadow them all. I believe all who have observed children carefully, as they pass through various stages in development, will agree that the child's ever-increasing power to control his aggressive tendencies toward his parents, his brothers and sisters and playmates, is one of the most outstanding and most remarkable features of behavioral growth, and there is nothing more alarming to society as a whole and the parent in particular than to note that this expected control of aggression is not taking place and that the child at times seems overwhelmed by his infantile aggressive impulses.

LET us consider the changes that must take place in the expression of aggression by the child as he develops, and secondly, let us examine the best, in fact the only, social setting in which such a necessary change is able to take place at all. And though we do not know how these changes take place in minutest detail, we do know enough in our present state of knowledge about human behavior to cite what conditions are needed, and must exist seemingly, in childhood, adolescence and adulthood, in order to bring about these changes. Now inasmuch as my present task in this lecture is to speak of the origins of aggression, I shall have to dwell upon the expression of aggression in childhood somewhat. The others who follow me in this lecture program will specifically speak to you concerning aggression at the college age level, and in relation to the topics that are so pertinent to this stage of growth. However, I do hope that by self-reference you perhaps can see some of the vestiges, in you or in others, of this struggle with this impulse that goes on from childhood upward.

In the first place, there must take place as the child gets older a modification of the aim of his aggression. While at first, and for a number of years of early childhood, frank aggression is aimed primarily to effect destroying, eliminating, breaking, mutilating or causing damage to the body or to the possessions of another person, there is, or there should be, a gradual replacement of this aim by socially acceptable aims that merely carry out such destruction, elimination or alteration or damage in a symbolic or fantasied manner. The fantasied soldiers and cowboys, gangsters and Indians and Supermen, of the extremely aggressive era between five and six years and ten and eleven years, are examples of this partial modification of the child's destructive aims through fantasy, and indicate a phase or stage in the child's development in the control of his aggression. We must recognize this phase for what it is, and not hastily conclude that it is either wrong or abnormal. Only the prolongation of this stage into adolescence and adulthood should really worry us. Coupled with this change in the direction of increased fantasy, and less actual harmful intentions in play, there is an increase in the aim to master, not to kill or harm but to master, the other person in the environment, to try to make him or her do -his bidding, to overcome the frustrations, blocks and limitations that persons and even nature place in the child's way. In short, a desire for or an aim toward mastery of the world and its occupants replaces the aim to destroy or damage them. And herein we discover one of the elements of the constructive and worthwhile aspects of aggression.

A second and at least equally important change in the character of the aggressive behavior in children is the gradual impersonalization or de-personalization of the object (not the aim, now, but the object) against which the child is hostile or aggressive. In the earlier years, the child directs his aggression against the people in his world about him, his parents, his brothers, sisters, playmates. But just as the aim of aggression changes from destruction to mastery, so also does the object of these aims change from persons, and the bodily parts or possessions of persons, to things. To summarize this process of change, we would call it impersonalization of the child's anger or hostility. The frustrating things or events or circumstances are inanimate objects that gradually replace people as the recipients of aggression and hate, and though minor and imperfectly carried out in earliest years, later they can lead to the most constructive alterations and contributions that we can make, as individuals or as members of social groups. This impersonalization or shift in the objects of our aggression from persons to things must include not only our parents and siblings but also it must be thoroughly generalized and thus include a re-direction of our aggression away from age associates and away from groups of people in our immediate social milieu and also from those who differ

from us in race, religion or economic standing. That adult who forever remains a child in this aspect of his development will always need a person or a set or group of persons against whom to hurl his hostility. As you will see in a moment, aggression in this form or guise - we call it prejudice —is really the continuation of a battle against others than the hated group or the hated race, and is in reality a continuing sham-battle against a feared and suspected enemy of very earliest years, namely father and/or mother.

IT is important for us to examine how or under what circumstances this orderly and wished-for development takes place at all, in order that we may prevent unfortunate deviations, blocks or delays in our children's development of the ability to control these impulses. As I said before, we do not know the detailed "how" of the process, but for many years we have had a really definite idea of the only climate or setting - that is, the "emotional climate" - in which the child will be able to develop along these lines. We recognize in the light of repeated case histories and intensive psychoanalytic studies of children at all levels of development that primitive aggressive responses can be modified in the manner we outlined above only when the child senses that he himself is not in danger. If the infant, or even the school child, or the adolescent for that matter, senses a feeling of hostility, of rejection, lack of love or interest, on the part of the most important people in his environment, namely his parents, the destructive aspects of aggression and those directed against people are called forth as they are in earliest infancy, and the expected modification toward impersonalization and constructive mastery will not take place. Actual or implied threats of abandonment, or desertion, by either or both parents, bodily harm, threats of mutilation, corporal punishment, all of this will tend not only to block the development of a child in this area, but will tend to undo the advances already made. In the latter case, destructive aggressive acts directed against actual persons result. Thus the unwanted or destructive type of aggression in all children is seen to arise when their anxiety or sense of danger is aroused by possible impending insecurity. Hence, in short, the more primitive destructive mutilative person-directed type of aggression cannot be given up by us nor can the educative constructive non-person type of aggression be given expression, except in an environment, family, and later social, or even college environment, that makes the individual feel a certain degree of security. The danger that negative hostile feelings may replace the positive and secure relations with their parents makes for an anxiety that can allow them only an endless repetition of the older protective aggressive responses and inhibits all attempts at newer types of response or experimentation. In short, learning and development cease, in such an unhappy emotional climate.

These, then, seem to be some of the steps with which the child is confronted in his attempts to gain control and obtain a socially satisfactory expression of his aggressive instinct. We have emphasized the environmental setting necessary for carrying out this task in development. Before passing to a discussion of the types of aggression, good and bad, which we encounter in individuals, I would emphasize too, for the benefit of us who are now adults, that this control of aggression is a continually reappearing task which we ourselves have to solve and re-solve day after day throughout all our lives in our relations with other people.

LET us examine now some of the more important expressions of aggression that we do see, or better, let us consider what are the various purposes for which the aggressive act is used by children. In the light of some of the meanings or purposes of this behavior, we may be the better able to cope with it when it arises.

A type of aggression which is very well known to you, which occurs at all stages and levels of development up into adulthood, is that aggression which is fundamentally attention-getting. In the earlier age groups, the very appearance of the parent or another adult may be a signal for a child to become aggressive toward his brother or sister or even toward an adult in the group. It is obvious that such behavior is an attempt to gain and hold the attention of the adults present and to exclude from attention all other persons in that particular milieu. It is as if the individual were seriously threatened every time another person came on the scene, threatened in that the other may draw unto himself or herself the love and attention that the individual feels he himself must have and have alone. Hence the aggression is but a thinly disguised attempt to eliminate the person against whom it is expressed. It is also many times true, unfortunately, that the child and the adolescent and the adult in some way learn that a show of aggression, or "fighting spirit" as it is called, is not only condoned by the parent and others but is in fact encouraged as a sign of accomplishment, an indicator of masculinity, a badge of courage.

In the second place, and closely allied to this of course, is the aggression expressed in order to demonstrate superiority. This is designed primarily to demonstrate superiority over others in any particular group one enters. This type of hostility again is seen in younger children and it is not unusual that it is tried within the family group. In such a setting the aggressive child is for some reason unable to obtain the satisfaction of being loved, wanted, or sought after, perforce of his usual and ordinary behavior. Hence he has to gain this satisfaction by impressing the adults with his physical superiority over others. And those who are inferior physically, due to slow development or handicaps, will tend to be aggressive toward those who are stronger, taller, brighter, or even better looking, in order to gain actual, or fantasied, recognition.

In the third place, we recognize a type of aggression which is known as protective or defensive aggression. Those who have been hurt, physically or emotionally, or who fear that they are about to be hurt by others sometimes become very aggressive as a defensive measure. This is the

counter-aggression that is so often commented upon in the literature on this topic - that is, a response to actual or threatened frustration by another. Here again the aggression used in defense can be multilative, destructive, and person-directed in type, or can be of the more mature non-personal type. Many child psychiatrists and psychologists stress this type of aggression, namely counter-aggression, as the only type of aggressive response, and state that aggression is always a response to some frustration, to the exclusion of all other types of aggression that one might mention.

In the fourth place, there is a type of aggression which we would call inverted aggression. There are times when the individual directs his aggression not against the outside material world or against the people in the outside world but directs it against himself. We say his aggression is inverted. Here the individual seems unconsciously to wish to punish himself for misdeeds that he has carried out or for which he feels inwardly guilty. And many times, unfortunately, he is unable to locate the source or nature of his guilt feelings because they are largely unconscious. An example of this is the well-known "temper tantrum" which is a bit of behavior where the child in frenzied fashion is violently aggressive toward himself with blows and banging of his head and body on the floor. His aggression, usually aroused as a response to some persistent frustration in his environment, is expressed, as you can see, both against the outside world and the people in it, and against himself, one and at the same time.

Another and much more subtle way in which the individual inverts his aggression and directs it against himself, on his own body, is seen in the person whom we describe as "accident-prone." There are children and adults who I'm sure you have known who are continually and repeatedly hurting themselves. Or they get themselves into positions where it is so inevitable that they must be hurt by something or somebody that we recognize in them a strong, unconscious drive to punish themselves, to cut and bang and scrape themselves, to smash themselves up in cars and in sports, as if there were an unconscious compelling force, such as guilt, making them do it. An analysis of such cases usually does reveal strong needs for punishment which they are carrying out by allowing physical harm to come to them. (Parenthetically, I would hope that you gentlemen who insist on jumping off those horrendous ski-jumps each winter would examine the motives that compel you to take such risks, particularly if you are always getting hurt at it!)

A variant of this previous type of aggression toward the self is the much more prevalent use of aggressive behavior to invite punishment by others. In other words, the individual may feel very guilty for some wrong-doing for which he has not been found out and hence has not been punished as he unconsciously feels he should be. Such an individual will engage in open, flagrant and perhaps serious aggressive acts, in order that he may be punished by someone in his environment. This punishment in turn resolves his feeling of guilt and his need for punishment for the aggression of the moment and for the undetected evil-doing as well. This mechanism is seen to be at work quite frequently in the cases of delinquent boys and girls, wherein it is to be noted that they engage in delinquent acts again and again until getting caught and being punished makes them feel better. Many times they accurately predict their future detection and punishment by the police and courts, and curiously enough they often do something in the criminal act itself that makes it inevitable that they will be caught and punished. In other words, these are the types of people who are seeking punishment by their aggressive acts toward their environment for some crime or wrong-doing they feel or dimly think they have committed. And they will continue to do this until they receive help and insight relative to their own unsuspected drives.

And finally, in this section on aggression in regard to its development and manifestations in childhood and adolescence, I wish to comment upon another expression that is particularly distressing to others, namely, aggressive silence. In other words, we recognize in our field an individual who is given to a type of chronic intermittent non-communicative aggression. If you have ever been endowed with a roommate who makes this type of response, you can agree with me, I think, that it is a particularly obnoxious type of aggression. The individual from time to time lapses into silence in the presence of the person against whom he feels extremely aggressive. This silence, in the case of marital affairs, sometimes lasts for weeks or months, and suddenly the individual comes out of it and is no longer non-communicative and aggressive for a few months and then just as suddenly goes back to this punishing response. This type of behavior is not going to lead to hospitalization but it is very serious from the point of view of those who have to live with the individual so prone to its use.

These then are some of the origins and early-life expressions of aggression that should act as a frame of reference for you as you consider this problem as a part of your own life as college students, and as you review specific types with other lecturers in this course.

AT this point, and to the end of the hour, I would like to comment upon some general tasks in mental health that confront you as students and how your higher education in which you are now engaged may contribute to their solution. These have more than tangential reference, I assure you, to the control of your aggressive impulses.

In the first place, I would have you note that the aggressive person must be studied as an individual if you are really going to get at what he's trying to do or the meaning of the aggressive act he is carrying out. However, there are certain generalities that I'd like to point out regarding your own problems with aggression. There is, for example, a mental health task in these college years that it is necessary for you to solve, and that task involves the modification of your feelings towards parental figures. I need not emphasize with you, and particularly I need not emphasize with your parents, that a youth —an adolescent youth (and I'm trying to avoid that term "adolescent" as much as I can) - seemingly must take his initial steps toward independence and emancipation by a very aggressive process. This aggressive process usually is characterized by devaluing father and mother and renouncing much in the way of ideas, ideals, loyalties and values that the parents have tried to instill from earliest years. This devaluation of the parental figures may come early in adolescence, but come it will, soon or late, and it usually prostrates the parents of the adolescent for the time being. If they can just stand such punishment for a few years they will be rewarded, I think, by a return to favor in the eyes of the youth, when the latter has acquired a more realistic estimation of their value. In regard to this aspect of personality growth, my thesis is that an institution of higher learning, a college, should assist, by the very fact of your being in college, in the solution of this task in mental health. For in the light of extensive and intensive knowledge of the hard-won ideals and values of the ages, emphasized and re-emphasized for you in the college, the parents and their values, I think, usually do not come off so badly by comparison. The parent may not have had the words by which, or the name of the philosophical system or rubric under which, these social, moral and ethical principles are explained or subsumed, but it is not unusual for the student to consciously or unconsciously recognize eventually more than a coincidental similarity. At that point, the students' parent-estimates change, and they change in the direction of realism and maturity, and youth-parent relationships change for the better. And of even greater significance, the youth has completed another step in personality growth.

There is, however, one aspect of growth at this time of life which is paradoxically a rebirth of faith in a type of thought of inestimable value, which is characteristic not of adulthood but of infantile thinking, but is, I will have you note, free from the aggressive aspects of behavior that are usually seen in those early years. I refer here to intuitive thinking, and specifically, to a re-trust in our own generalizations and formulations. The creative curiosity, the free interpretations and associations, allied with innermost feelings, needs and fantasies, that constitute the joyous aspects of learning in infancy and early childhood (and I think you will agree that the learning child shows considerable glee in learning), these later are subjected and subjugated and depreciated by the necessity for acquiring the so-called hard facts and figures of this world, and in many instances this earlier type of intuitive thinking is lost forever. It is not only through a college education that the reawakening of these creative potentials of the personality is accomplished. It does happen elsewhere. However, I'm sure that even the dullest of us under the impact of our associations with creative scholars and the creative contributions of past centuries have ourselves experienced the elation that accompanies our own re-discovery or our own re-formulation of a scientific fact or plausible and sensible theoretical construct. It's of little import, really, to you as college students that it may later be demonstrated to you that this is a re-discovery. For you, it was independent and creative thought. If your college through the excellence of its teaching affords you a series of such independent re-discoveries, as answers to your curiosity, aggressive though it may be, then the college has aided you in your development toward a life of creative work. So far as I know, this is the only instance where a regressive-like maneuver of man to babyhood or to an infantile type of thinking is really a step forward in development. And this maneuver, I submit, does constitute an element in personality growth and a thrust toward maturity. This is the expression of aggression, if you will, in its most sublime and constructive form and it is the repeated experience of this sort, in college years and university life, that drives the scholar unceasingly to his task.

FINALLY, I would like to turn attention to aggression in relation to one of man's greatest triumphs, though complete triumph does not yet seem over the horizon. This is a triumph in relation to control of aggression among men living together in groups. For example, on the one hand, the medical social scientist is acutely conscious of the fact that the central and nuclear impulsions of man are his destructive and aggressive tendencies, and he notes them at all levels of organic life and as traceable up through the developmental stages of the individual. In other words, it seems that man - all men - holds a naked dagger in the hand, and he holds it by the blade. There is no handle. If he slashes his neighbor, he slashes himself too, and the laws in this area and with respect to this behavioral process seem to be inexorable either for the individual intrapsychically or for the social group. These are the findings and I think you would expect that the psychiatrist would be discouraged and cynical and depressed, and would run from his consulting room yelling, "All is destruction!" But such is not the case. I think most of us who study human behavior at close range are optimistic about human beings, and we are particularly optimistic about youth. The basis for my own optimism is that I feel that men and women both as individuals and when living together in groups are at last not afraid to recognize man, including themselves, as he is, with all his destructive tendencies, and are seriously endeavoring to do something about him in as careful and practical a manner as the present state of our knowledge about human behavior will allow.

It seems to me that our fundamental hypotheses and our assumptions about man today are much more realistic and more exact than ever before, as we attempt as individuals or in groups to design individual life-programs or attempt to design national or world-wide experiments to control aggression. More individuals than ever before, and also more societies, ethnic groups, nations and groups of united nations, are well aware of the fact now that the central problem of individual living and of groups of individuals living together is the problem of control of hostility and aggression. To return to my analogy, it is as if groups or nations had at last shared intuitively and almost concomitantly throughout the globe the notion that they too are holding a handleless sword by the blade. Individuals sometimes, and nations always, have paid a terrible price in happiness and efficiency before acting on these insights regarding the nuclear drive in man. But they are acting upon these insights now and we most decidedly are on our way to the establishment of individual and social programs for effective living.

But what is the meaning of all this in respect to the mental health resources of man and particularly the idealism of youth and college youth? I think it is just this: that as you advance through college and try to solve these problems that are related to your own growth and mental health, you may be projected toward a position of cynicism or lack of idealism - we expect young people to pass through that, but they thereafter live efficient and mentally healthy and worthwhile lives. What brings this about? It seems to me that it does not result - and will not result in your case - from a denial of the realities of your own individual instinctual drives or those of others. Nor does it arise from a dictated or superimposed conviction that this is the best of all possible worlds, because it probably is not. On the contrary, it arises first of all from a realistic acceptance of the basic impulses of man that I have outlined, and secondly from a realistic evaluation of the intrinsic potentialities for good as well as for evil in these basic human tendencies. For in spite of the presence of models of human behavior that are detestable, that one sees on all sides, there are present also models of human behavior that are admirable in that they direct their hostility and aggression toward evil and against all individual and social ills. These are the models for identification to which university and college students turn. And they are the models for identification which all of us need and crave as the only solution for our inner conflicts and impulses. The life programs of such models exist in the scholars in the university who are dedicated to their tasks and they exist in abundance in the lives and accomplishments of other people, living and dead, who will become known to you indirectly through their imperishable contributions to the progress of man and the control of his aggression.

Sooner or later to all people comes the unexpressed conviction that if one is destined to be aggressive, if one is destined to struggle, if that is the primary biological pattern of one's expressed energy, a certain proportion - a large proportion, we hope - of this energy may well be invested in a struggle for some social good. Now I say that in your development toward maturity and mental health, it is just at the college age level that youth becomes the idealist, but with an idealism shorn of all those fantasies of earlier childhood and an idealism that re-invests with interest, concern and value his inter-personal relationships within his family and within his society. This is the secondary idealism of mature adulthood that certainly is distinguishable from that primary infantile type that is embodied in the wishes of the young child. And I would say, finally, that a society, a college or any other society, may well be judged as good or bad to the extent that it offers to men, and to youth particularly, the necessary social instruments to carry out this worthwhile aggressive activity.

Dr. Gardner's article is based on the lecture he gave November 17 in the required freshman course The Individualand the College. We are pleased to print it as an effective means of giving alumni some idea of the content of the course, and beyond that, we are sure that Dr. Gardner's analysis of behavioral development will be especially interesting to all who are parents.

The Author Director of the Judge Baker Guidance Center in Boston since 1940, Dr. George E. Gardner '25 started out as an educational psychologist. Receiving the Ph.D. degree from Harvard in 1930, he served for eight years as psychologist at McLean Hospital. He was awarded the M. D. degree from Harvard in 1937. Dr. Gardner now spearheads the attack on the emotional and behavioral problems of children, in a joint enterprise of Harvard Medical School, Children's Hospital and the Judge Baker Guidance Center. He is also Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard and Psychiatrist-in-Chief at the Children's Hospital.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePublic Interest an The Technological Revolution

February 1955 By LLOYD V. BERKNER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

February 1955 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES JR., TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

February 1955 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleThe Underĝraduate Chair

February 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

February 1955 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, CILBERT H. FALL, FREDERICK CHASE

GEORGE E. GARDNER '25

Features

-

Feature

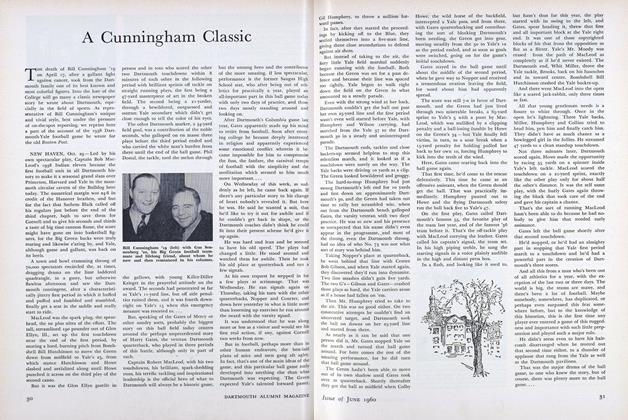

FeatureA Cunningham Classic

June 1960 -

Feature

FeatureDr. Carleton B. Chapman Appointed Dean of Dartmouth Medical School

JUNE 1966 -

Feature

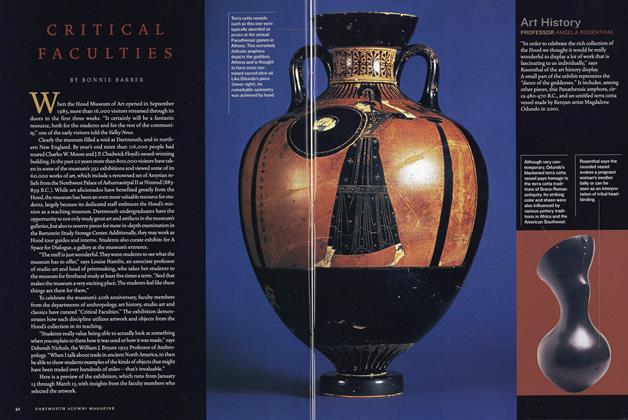

FeatureCritical Faculties

Jan/Feb 2005 By BONNIE BARBER -

Feature

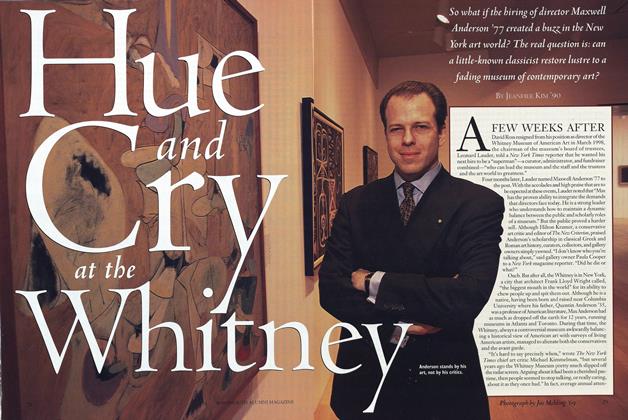

FeatureHue and Cry at the Whitney

MAY 1999 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Feature

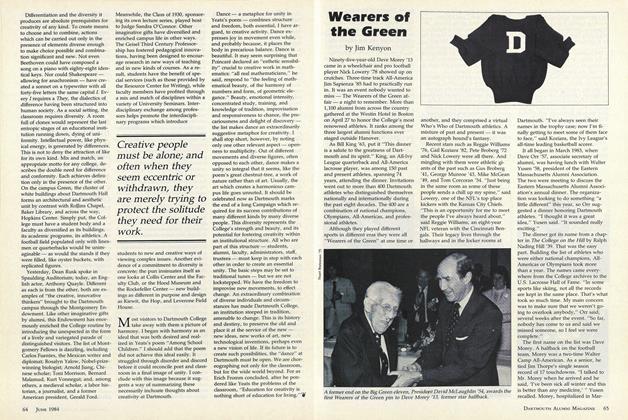

FeatureWearers of the Green

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

Feature1958 ALUMNI FUND REPORT

DECEMBER 1958 By William G. Morton '28