"We thought of ourselves as living in a post-heroic age, a time not of heroes but of anti-heroes."

As i pass students walking across campus, I often think of myself when I was a student, uncertain of what my calling in life might be, yearning for a great cause on which to focus my energies.

My own college years were during the Eisenhower administration. A pervasive grayness hung over us a fine silt of ennui that filtered into our dreams and dimmed our inchoate aspirations. We thought of ourselves as living in a post-heroic age, a time not of heroes but of anti heroes-diminished, Kafkaesque figures whose brooding alienation and misunderstood sensitivities expressed the shrinking limits of the human condition. We saw our world reflected in T.S. Eliot's TheWaste Land and The Hollow Men. Our novelists were Albert Camus and J. D. Salinger; our filmmakers, Ingmar Bergman and Francois Truffaut; our playwrights, Samuel Beckett and Edward Albee; our philosophers, Reinhold Niebuhr and Jean-Paul Sartre. Looming over us as a popular icon was the tormented figure of James Dean, the "Rebel Without a Cause."

Yet in spite of our detached style and passive demeanor, many of us cherished a deep longing for genuine heroes, leaders with unifying visions, who would energize our imaginations and imbue our individual lives with a larger purpose. As Bernard Malamud wrote in The Natural, his haunting fable of a superachieving baseball star: "Without heroes, we're all plain people and don't know how far we can go."

Today's students have, if anything, even more misgivings about the concept of heroism than my generation had. But the fact remains that some lives are so wisely focused, so humanely directed, that they elevate those who study them. We need the example of men and women who, by their actions and achievements, inspire emulation; who, by the conduct of their lives, give distinctive and concrete form to their highest ideals.

Let me tell you about one person whose life and work made her an exemplar for me: Eudora Welty I first encountered her work when I was an undergraduate. Her greatness as a writer rests, in large measure, on the intensity of her experiences and observations, as both a southerner and a woman. In work after work Welty brings into the mainstream of our awareness the overlooked, the undervalued, and the marginal.

Her work is in the great tradition of Jane Austen, characterized by a wickedly playful wit, an exquisite ear for dialogue, a nuanced sensitivity to the small, everyday dramas of shy courtships and polite insults, and most of all by the universe of meaning that is revealed in the mundane fortunes of a single household.

The source of Welty's subde powers of observation, compassion, and insight remains a mystery of the kind with which creative people so often confound us. In her own account of her origins as an artist, Welty has said only, "My imagination takes its strength and guides its direction from what I see and hear and learn and feel and remember of my living world. But I was to learn slowly that both these worlds, outer and inner, were different from what they seemed to me in the beginning."

With grace and energy, Eudora Welty has taught us that we have worlds to learn from a woman who has never married, who has rarely traveled, and who still lives in her childhood home. Welty developed her private self even as she observed and engaged the public world. As she explains in the closing words of her literary autobiography, "A sheltered life can be a daring life as well. For all serious daring starts from within."

This essay was adapted from last September's convocation address.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

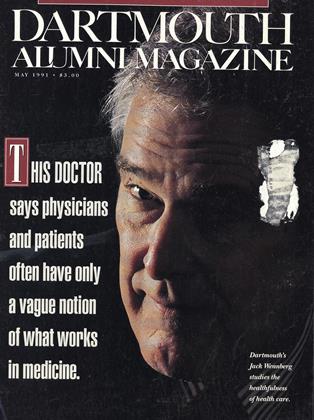

Cover Story

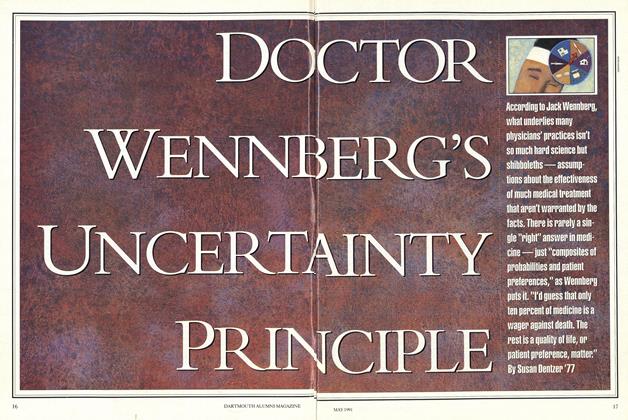

Cover StoryDOCTOR WENNBERG'S UNCERTAINTY PRINCIPLE

May 1991 By Susan Dentzer '77 -

Feature

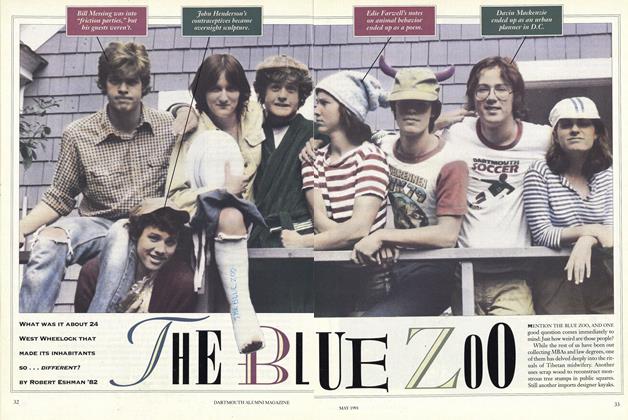

FeatureTHE BLUE ZOO

May 1991 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureStory Time

May 1991 By Nancy Millichap Davies -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

May 1991 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleTHEATERS OF WAR

May 1991 By Professor Lynda Boose -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

May 1991 By Michael H. Carothers

James O. Freedman

-

Article

ArticleTHE PROFESSOR'S LIFE

FEBRUARY 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA ROBUST INTELLECTUAL

APRIL 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA New Dartmouth Tradition

June 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWorries of a President

May 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Time Allotted Us

June 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeatureAn Honor, To a Degree

Sept/Oct 2002 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN

Article

-

Article

ArticleOTHER! TRUSTEE ACTION

January, 1911 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Establishes National Enrollment Group

March 1954 -

Article

ArticleLazarus Heads School Study

March 1960 -

Article

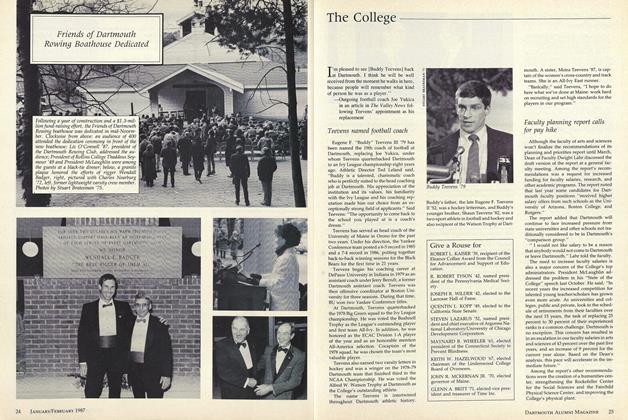

ArticleFaculty planning report calls for pay hike

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 -

Article

ArticleLet It Snow!

Jan/Feb 2011 -

Article

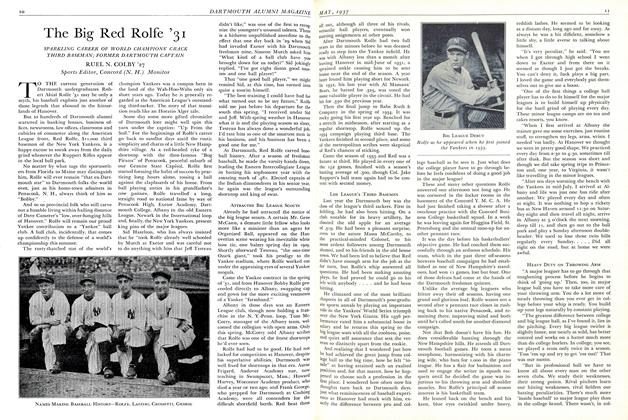

ArticleThe Big Red Rolfe '31

May 1937 By RUEL N. COLBY '27