WRITING in bronze or granite demands a fine sense of artistry and a strong wrist. The mere nuisance of melting down or resurfacing one's medium presupposes more than ordinary care in the composition of dicta made permanent in metal or stone, and the authors of such inscriptions must watch their p's and q's and dangling participles. Furthermore, deathless prose comes hard, and it is rare indeed to find examples, among inscriptions in the vulgar tongue, as impressive as "Through these doors ..." or "Upon the fields of friendly strife...

("Gloom of night" is, of course, a steal from Heroditus, and "Passengers will please refrain ..." is hailed rather for its rhythm than for its philosophy.)

The College is liberally stippled with inscriptions, but can boast small Latin and less Greek. Apparently the Golden Age was not coincident with the Bronze Age on Hanover Plain. Never a Dulceet decorum or even a Haec olimmeminisse graces our halls, the only notable exception being a phrase in halting Latin (Tully, my masters? Ulpian serves his need!) glorifying fabricated ice over nature's brew—a sentiment which, no matter how enthusiastically applauded by the Thayer School engineers, is frowned on by Humanist and Romantic alike. Another exception is the occasional repetition of Vox clamantis in stained glass, but glass and gravestones and the Associated Schools are not included in our study.

Although a tour of College buildings is more properly matter for a May morning, we recently took advantage of a break in the temperature (nature's and our own) to sneak a hurried glance at likely loci of descriptive and commemorative labels. Most of our structures, like most papers at the meetings of learned societies, are signalized "by title only" - modest dog-tags to serve as a guide for freshmen and Congressional investigators. Wilson and Thorn ton Halls are - though only recently - more informative. The porch of Wilson sports two large brasses, one a narrative of the rape of its store of books by Baker Library and the other telling of its acquisition of fauna, flora and fossils attendant on the sacking of Butterfield. The Thornton Hall entry carries a generous tribute to John Thornton of Clapham, "The friend of humanity and ornament of the age in which he lives" (Charity, 244-255 - whatever that is).

Dartmouth Hall, in addition to the familiar apologia for its two midget windows, has affixed to its latest cornerstone a bronze tribute to the sixth Earl. The rest of the "Old Row" is devoid of comment, wearing its chaste beauty glorious but mute, and Rollins Chapel is equally uncommunicative (except that the curious may find Gloria in excelsis in scrabble on its ceramic wainscoting). But Parkhurst, Robinson, Sanborn and Carpenter all honor their donors with plaques, and a marker on Crosby glorifies the first identification of "rock oil," in genuflection to the petroleum industry.

The Gymnasium and its adjuncts are more generous with their display of bronze - sociable and discursive while the nobler seats of social and linguistic learning remain taciturn. Each unit of the athletic plant carries a bronze notation of its donor or donors, and the dedication of men's lives as well as their funds is memorialized by several tablets on the walls and on the playing fields.

The record of the fame of the men of Dartmouth who died in the first World War is borne on a towering slab of granite at the entrance to the Stadium, and the memory of Richard Neville Hall of the American Field Service is enshrined in Baker. But the most impressive memorial in the College is found in the great bronze doors of Webster, on which are listed Dartmouth's many sons who served with the Blue or the Gray in the War between the States. In Webster also is Joseph Hopkinson's felicitous thumbnail history of the early College: "Founded by Eleazar Wheelock, refounded by Daniel Webster."

Among the insensate multitude who daily pass these inscriptions there must be some who pause to read and ponder battles long ago. Lives and philosophies have been shaped by unconsidered trifles, and if a chance professorial word may contribute to the uncommon intellectual experience of even a few, what greater responsibility rests on him who selects a word to be cast in bronze or carved enduringly in granite - even though the word be only Ozymandius.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Dartmouth Rhodes Scholar Writes Home About Oxford

March 1955 -

Feature

FeatureTHE BEGINNINGS of Dartmouth's Alumni Organization

March 1955 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS 01 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1955 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Article

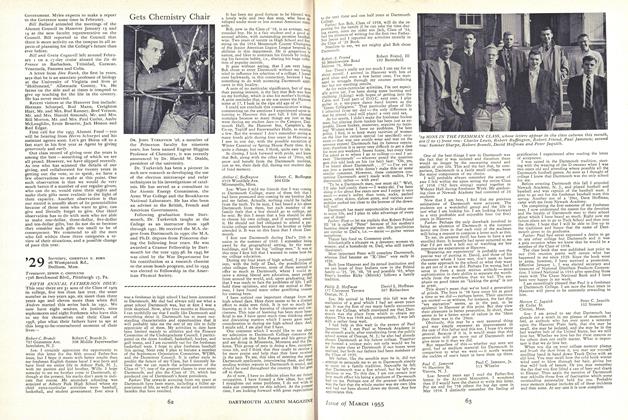

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1955 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES JR., TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE

BILL McCARTER '19

-

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

October 1954 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

October 1955 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

March 1956 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

June 1957 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

December 1957 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

March 1958 By BILL McCARTER '19