ON August 1, 1066, give or take a few years, we received a letter from the Dean to the effect that we were accepted for admission to Dartmouth even though our preparation had been somewhat irregular. The good Dean continued that our lack of a fourth year of Latin and our total lack of Greek made this a slightly dubious procedure on the part of the College, but that if we could make up the deficit on the side, we could come along. Amherst and Williams were not so tolerant and, as a result, we packed our straw suitcase, donned our purple suit and raincoat, and arrived in Hanover to be sold decrepit furniture by Carl Eskeline and a laundry contract by Pete Soutar, and to set up residence in the malodorous but congenial confines of College Hall.

As we recall it, there were four classmates with similar lacunae in their classical equipment, who joined us to study Virgil under Myra Hastings in the Hanover High School along with Dolly Gile, Kay Lay cock, and Jimmy Wicker. We have retained small Latin and less Greek, but 65 was the certifying grade, and all five of the college freshmen got 65 in Virgil. Four years later, thanks in part to a judicious election of courses in Biblical Literature, Astronomy, Education, and War Aims and Issues, we received a degree on the same occasion that Irving Cobb was granted a slightly superior one. He remarked then that he felt like an egg that had been laid twice, both times successfully. Our claim was more modest, but our pride no less weening.

We have occasionally wondered how we and our contemporaries would have fared had the Selective Process been in operation in our day. This innovation was established in 1921, and gradually reduced the slap-dash admissions hunches of Chuck Emerson and Craven Laycock to an increasingly sharp series of calculated risks. Initially the target of scorn for some of our step-sister institutions, the many merits of our system have been surreptitiously copied with various local dealers' trademarks, although some still officially cling to their original College Board patterns, seldom admitting more than 70% of any class by the Dartmouth plan.

Here, today, "candidates for admission are evaluated (a) in terms of academic promise and (b) in terms of their personal qualities. Personal qualities are evaluated in terms of (a) breadth, (b) depth, and (c) force." Among the variegated behemoths and wisps of our day there were a number who were of questionable (a) academic promise, but we were rife with (b) personal qualities, and nobody could sing Chinatown like Harry McDevitt. At that time the colleges were not in a sellers' market, and population curves, and tuition charges, had not begun to leap and bound.

After every war our nation puts on, there is a rush on college admissions, and Gordon Bill and Bob Strong, and now Al Dickerson, have had to tread a fine line between being yes men and no-men; but they have done it courageously and intelligently, and if star halfbacks have scored against us, or stalwart guards (the mugs) have smeared our offense, or no-hit pitchers have hit us three for three, it has seldom been because they weren't accepted for admission by the College, but rather because our undoubted local charm was not effectively enough presented to keep them coming in spite of alien lures.

As a father who has recently fomented the acceptance of an application at a women's college and make no mistake, they're tough—we were torn between our parental fears and our sure knowledge of the solicitude of reputable institutions to garner reputable material. Our readers will no doubt be relieved to know that it came out all right, but the fact remains that college admissions are today a severe problem for parents, for alumni, and, most of all, for the colleges themselves.

Maybe we and our compeers couldn't make the grade today. We had never heard of percentiles, and still don't know exactly what they are. "Scholastic Aptitude" had not been invented in our time, but we had at least two things now rare among secondary school pupils nurtured on social studies and driver training. We knew arithmetic, and we knew the alphabet.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleTHE YEAR IN REVIEW

June 1953 By RICHARD C. CAHN '53, UNDERGRADUATE EDITOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

June 1953 By PHILIP K. MURDOCH., MARVIN L. FREDERICK -

Article

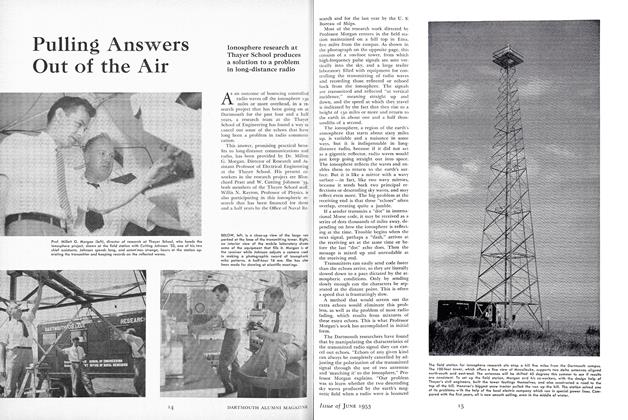

ArticlePulling Answers Out of the Air

June 1953 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1953 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

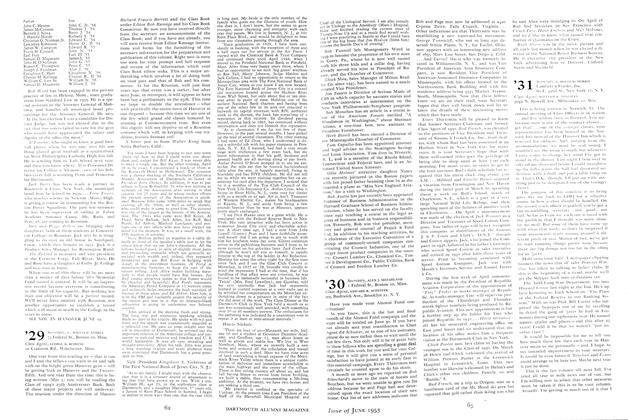

Class Notes1932

June 1953 By JOHN A. WRIGHT, JAMES D. CORBETT

BILL McCARTER '19

-

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago .... Fires

February 1934 By Bill McCarter '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

November 1952 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

October 1954 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

March 1955 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

December 1957 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleTHE HANOVER SCENE

FEBRUARY 1959 By BILL MCCARTER '19