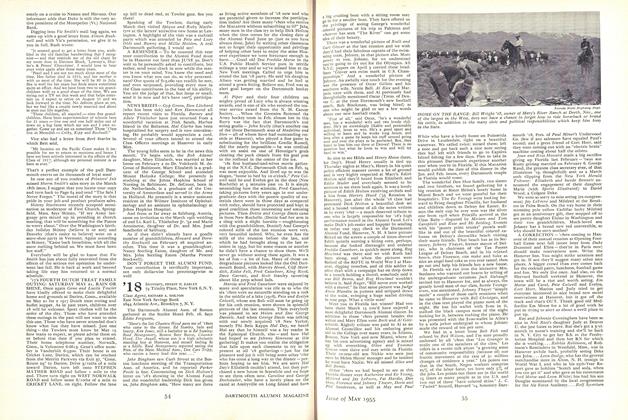

VICE PRESIDENT, THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION

I WILL start with a story on the theory that from it you will be able to gather some idea of what I am going to try to do this evening. The story is of a friend of mine who became a professor of medicine at Harvard but who got his medical education at the University of Budapest. We were talking about experiencing turning points, and he said, "I very well remember where my life went off to a new turn. In my first year as a student at the University of Budapest, we were going to have lectures in physics from a great Hungarian physicist named Eötvös, and he was ten minutes late, so we were all looking pretty hard to see what kind of a fellow would turn up. Suddenly the door swung open and an enormous man about six feet three with a long white beard came into the room with two big books under his arm. He advanced to the lectern and slapped the books down with a bang, looked out over the crowd of us, and said, 'I KNOW NOTHING.' Well, we were absolutely astonished. Here was the professor who said he knew nothing, and he repeated it in a loud voice, and then leaned forward and said, 'But, gentlemen, I have learned how to find out anything that I want to know.' "

Weiss told me that the most enormous weight rolled off his shoulders at that moment. He said, "I remember it well. I was sitting third from the aisle in the third row. I've never had a sensation of freedom to approach it. Now I know why I felt that way, but I didn't then. All I felt was liberated, and liberated to a degree that was wholly unexpected. The reason I felt that way was that quietly but firmly I'd been accumulating a conviction that I wasn't going to be able to get through medical school and wasn't ever going to know enough to take care of human beings."

Now the reason I want to talk to you tonight is not to give you a lot of information. I want to talk much more about ways that you may find useful in getting information for yourself. I think it is reasonably important to think about things like that, at your age. Goethe once said, "It's extremely important to look quite carefully at what you want most of all in the world, because you're so likely to get it." What I want to put up to you, partly as an advocate and partly to leave on your sideboard for you to take as you please, is what is meant by some of the things we call thelife of the mind - using your head, what kind of a life you get when you like to do that and do do it, what are some of the rewards, what perhaps are some of the penalties....

Now, the life of the mind - that is, using your head about things and really using it in the full and free sense - seems .to me to have these advantages. First, it has all the charm of discovery, and discovery at any time in your life, because as time goes on you can discover more and more things through using your mind. Second, it has the advantage of clarity. And third, it has the advantage of just plain enjoyment.

Now in terms of discovery, let me tell you something to illustrate the excitement of using one's mind. The German mathematician, Gauss, when he was nine years old in school, had put to him a question which I put to you. The teacher said, "What is the sum of one plus two plus three plus four plus five plus six plus seven plus eight plus nine plus ten?" These German boys of nine and ten started adding it up. Long before they'd gotten through, little Gauss's hand went up, and the teacher said, "What is the matter?" Gauss said, "Nothing's the matter, I have the answer." The teacher said, "You've seen this problem before?" Little Gauss said,

"No, I've never seen it before." The teacher replied, "May I have the honor of knowing what you think the answer is?" Little Gauss said, "Fifty-five" - and that is the answer. How did he do it? One plus two plus three Now this is using your brains, and it is — to me - almost an esthetic experience. Little Gauss said, "I just noticed" - and there is a tremendous lot in that phrase "I just noticed" - "I just noticed that the first number you gave us, one, plus the last number you gave, ten, makes eleven; that inside that, the second number, two, and the next-to-last number, nine, also make eleven. And then, inside that, three and eight make eleven, and then four and seven make eleven, and five and six make eleven. So I thought if you took half the number of terms and multiplied it by the sum of the first and last terms, you'd have the answer." Now that is the answer, and by that method I can give you the sum of all the numbers from one through forty quite quickly, because I add one and forty and multiply that by twenty. There you are. This really extraordinary business of seeing the relationships is one of the pleasures of using your mind. . . .

There is another side to discovery, which is that the life of the mind gets you in contact with a very wide range of very superior people, in the form of authors from any period in history. And for people who ever feel lonely - and there are plenty of them too, even in large cities - if you have relied on the life of the mind somewhat you've got a certain kind of companionship, not the give-and-take kind, unhappily, but at least a certain kind.

Then the life of the mind leads also to being yourself. There is a nice phrase of Paul Valery, in French: II faut vivrecomme on pense. Si non, tot ou tard, onfinira par penser comme on a vécu. "You've got to live as you think. If you don't, sooner or later you'll end up by thinking as you have lived." Therefore there is a certain freedom in the life of the mind. You are not absolutely the captive of your experience. Oscar Wilde once said a smart thing when he said that all criticism is a form of autobiography. In other words, you ask somebody his opinion of something, and he tells you quite a lot about himself when he gives you the opinion. A very good illustration of that was what the German general, von Blücher, said as his first comment on Paris, which was, Wasfur plündern!—"What a place to plunder!" Well, you see, that tells you more about von Blücher than it tells you about Paris....

The business of leading the life of the mind is also charming to me because of the extraordinary variety it gives you, even within yourself, at different periods of time. Plato said that the life unreflected upon is not worth living, and there is a good deal in that. He didn't say that the life not understood is not worth living. He didn't say that, and when I was perhaps four years older than most of you, my main problem was that I didn't understand life. I got a tremendous relief out of reading in Henri Bergson this simple statement: "Intelligence is only one aspect of life; there is also intuition, for example, or there is instinct. You can't define anything in terms of only one of its parts. You can't define a room by talking merely about the north wall, or the west wall, or about the ceiling. You can't define anything in terms of only one of its parts. How can we then, with our minds alone, understand life?" That to me was the most tremendous relief, because I thought to myself, "Good, if my intellect is not supposed to give me the full understanding of life, then I'll use my mind for what mind is good for, and I'll let the rest take care of itself."

Now, a little more carefully, what do I mean by this lite of the mind? We have a very funny thing in the English language - we have only one word meaning "to know." But German has wissen and kennen and French has connaitre and savoir, and as a matter of fact, gentlemen, there are two kinds of knowing, and it's extremely important to know the difference. One is the knowledge that comes from familiarity, and I can say that when I go home my dog will know me. That comes from familiarity and it does not depend upon either written or spoken words or upon pictures. And incidentally, that is the German kennen and the French connaitre; they make that distinction. The other kind of knowledge is when I say to you, "Pasteur was born in 1832," and you say to me in French, "Oui, je le sais." - "I know it." Well, you weren't there. It isn't a matter of your experience; somebody, either by written or spoken word, conveyed that to you, and so you say you know it. So there is the knowledge that comes through symbols, and that's one kind of knowledge, and there's the knowledge that comes through experience, and that's another kind of knowledge.

It is very interesting to reflect that of these two kinds of knowledge, each has its short suit and each has its own long suit. Now I could leave you to figure out what the short suits and the long suits are, but I won't waste the time. I'll simply say what you know perfectly well, that if you know something because you've read it, you don't have real courage about it. That kind of knowing does not give you guts. But that kind of knowledge - book learning, we call it - has an enormous advantage. It can be communicated indefinitely and it can be stored for very long periods of time. But the fellow who knows how to sail a boat has the knowledge that comes from experience, and it's harder than the devil for him to transmit it, and it cannot be stored - but, it gives him courage. That is, it gives him a sense of real competence. Now I am making a case for the life of the mind contrasted purely and simply to inarticulate experience, because of the richness of it, because it can be transmitted so much, and because it can be stored for long periods of time....

There's another side of this life of the mind that I want to put up to you for your own judgment. I think most of you have, or soon will have, contact with the theory that man differs from the other animals in many ways but in one way that is quite significant, especially for his culture and his ability to maintain his life among the other animals; and that is that relative to other animals man has an extraordinarily long period of immaturity and of getting ready to be mature. You can call it infancy, dependence, adolescence and so on, but it's technically in the general area of the first twenty years of his life. Then he has two go's of about equal length and then he's sixty, when mortality begins in rather lively fashion. At any rate, that's a long time to be relatively immature; whereas a chick can pick up its own food within twenty-four hours of hatching, and lots of other forms of life do not depend upon long periods of maturing.

Now, it is that long period of maturing that enables man to transmit so much of what he's learned, and for us to have cultures. All right, that sounds perfectly lovely, and nearly everybody admits it - that long period of learning which is characteristic of man. Then what do we do? We turn right around and take students into our schools at six years of age in the first grade, and in the natural course of events a great many of them graduate at eighteen. And then the ones that are particularly good in their studies we say are "bright." Why, they're not necessarily bright- they're just bright for eighteen. They might be growing slowly, and if we'd only let them alone, at twenty-five they'd be really good. But we put the clamps on and we say, "Oh-oh - no, I want to know whether he's bright or not, so let's give him an examination and an I.Q." And if he really hits it at eighteen, what are we doing, gentlemen? We're rewarding precocity. We're rewarding the very thing that we said just a minute ago was, thank God, not characteristic of human beings.

It's a very peculiar situation you are in. And I want to say to you, don't consider yourself, any one of you, the isolated, pathetic, unrecognized but nonetheless exceptional person who is not considered as bright as somebody else. Because your tempo may be different and you may be coming into your own stride at two to five or even ten years later than somebody else, and it isn't a question of your being dumber. It may mean that you have a different rate of maturing, and in this appalling system we have of rewarding precocity, you get left. That doesn't mean that you are really left; it means that you are out of time in exactly the way that the human race fortunately is out of time compared with all the other animals. In other words, you are taking longer to learn.

Now there is certainly one natural corollary that the human being has to slowness in maturing. He will have time to recognize and see in himself quite sharply his short suits as well as his long suits. And there may be examples where a maturity that is certainly going to come to him doesn't come promptly. I can remember perfectly well that when I was thirteen years old I started in with algebra and I didn't understand it any more than a hog understands Sunday. Yet when I got to be eighteen and began to tutor a kid in algebra, it was all perfectly clear to me, and in the interim nobody had taught me any algebra at all. My mind just became mature enough to take it on.

There is one thing I've always wanted to say to a class of this kind, because I have seen it in my own and subsequent generations. It's a thing that results in a perfectly stupid loss of headway and confidence and happiness, and that is this: Every fellow in this room has something he's a little bit unhappy about in himself, some soft spot, some inadequacy, some defect, and his reaction to any one of those things is a wellhidden variety of shame - he's a little bit ashamed of it. And then, curiously, the next step from this sense of shame is secrecy — he keeps quiet about it. And then, curiously enough, he entirely forgets that all the other fellows in his class have their own troubles they are keeping quiet about. He doesn't hear anybody else mentioning the difficulty that he's suffering from, so he concludes, foolishly, that he is alone in his defect. And this sense of loneliness and isolation is more troublesome than any sin I can think of, because the sense of isolation goes on to self-pity, to self-hate, to depression and fear. He thus gets into an emotional jam because he forgets the simple fact that he'd have heard a long time ago about other people having his difficulty too if they had been candid in talking about it. He wasn't candid; they weren't candid; so he concludes he is alone in having his particular difficulty. If the other fellows in the class would speak up, you'd be surprised at the number of persons who are having the same difficulty you are having. .. they are just not talking about it. You are not alone.

Now, for each of you with a special assortment of abilities and defects, some of them not yet declared, some of them not yet formed, what is your essential problem as a freshman at Dartmouth? I hold that it is what the artist calls the problem of style, namely, to react to life in the fashion that is characteristic and honest of you. That's what the artist calls the problem of style, painting as he feels he sees things and as he wants to paint.

That may be a fancy name for it, so I can give you a somewhat simpler example. When Percy Haughton was given his contract to coach the Harvard football team, for the second period of three years, they gave him a dinner. He'd had a certain amount of grief and unhappiness the first three years of coaching because there was too much graduate interference with him as coach. And at that dinner, Mike Farley turned to Percy and said something that I think has great permanent wisdom. He turned to him and said, "Percy, you may not lick Yale under your system but, God knows, you'll never lick Yale under somebody else's system." Now there again is the problem of style. You've got to do it your way, and you've got to find out by trial and error how to do it your way. Finding your way involves, gentlemen, a certain amount of grief and frustration. And how you handle your failures is perhaps secondary in importance only to how you handle your successes-and that's still harder. ...

Now one more thing in point of strategy, this business of deciding when and on what you will engage your strength. I think it will increase your strategic wisdom if you deliberately set yourself in this college, sometime before you are through, the assumption of some responsibility. That teaches you an awful lot, and it teaches you a lot in the field of values. I also would commend to you something that I'll tell in the form of a story, and then I'm through. On November 5, 1928, as I was coming home from Latvia, I had four hours to spend in Berlin - time to kill. I went over to the Adlon Hotel to see who had been elected President of the United States, and, as I expected, it was a fellow by the name of Herbert Hoover. I still had some time to kill, so I sat down and said to myself, "I'll write a forecast of what will happen to the temperament of Herbert Hoover in the White House." I thought I could write it pretty fast, but I found, as a matter of fact, that I couldn't write it so darn fast. And I found myself asking a lot of consequential questions. But I finally got two pages done, and I kept it, without showing it to anybody. Later it made extraordinarily interesting reading to me, because it showed me what a fool I'd been, to leave out so many things that I should have been mindful of. Now if you want to increase your interest in any phenomenon whatsoever of human life, just force yourself to write down a forecast of what is going to happen, and you'll find that it does sharply increase your interest in what's going on. As the simplest illustration of it - if you bet ten dollars on a horse race, are you going to find out more about the horse and the track or aren't you? Well, the chances are that that betting, that committing yourself, that making a forecast will increase your interest. So let me make this request of you: please do increase your interest, and to some extent involve your mind in the business.

"The charm of discovery ... the advantage of just plain enjoyment."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

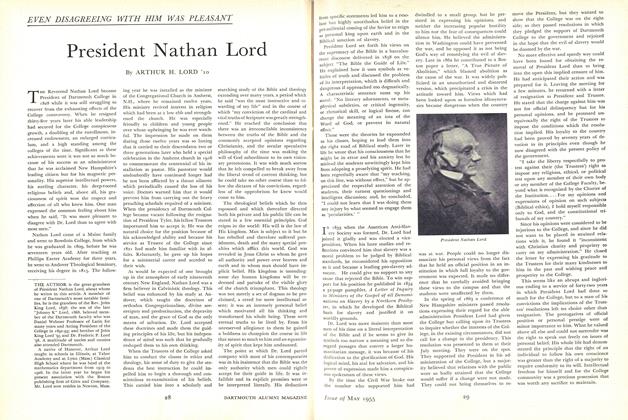

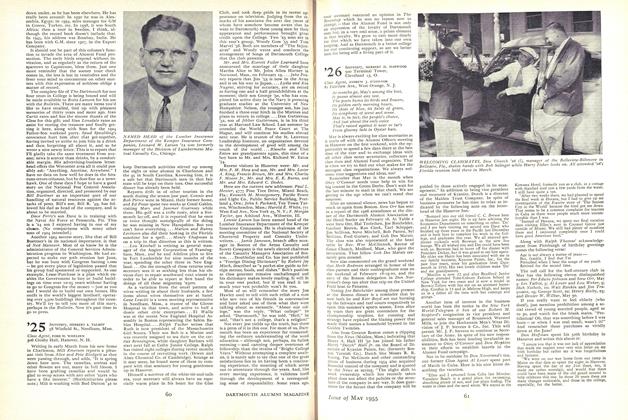

FeatureEVEN DISAGREEING WITH HIM WAS PLEASANT

May 1955 By ARTHUR H. LORD '10 -

Feature

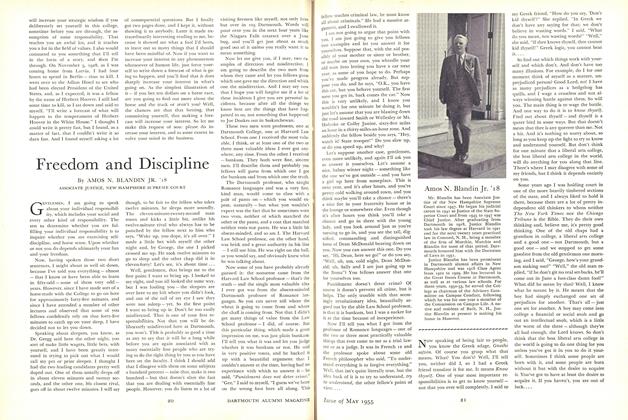

FeatureFreedom and Discipline

May 1955 By AMOS N. BLANDIN JR. 18 -

Feature

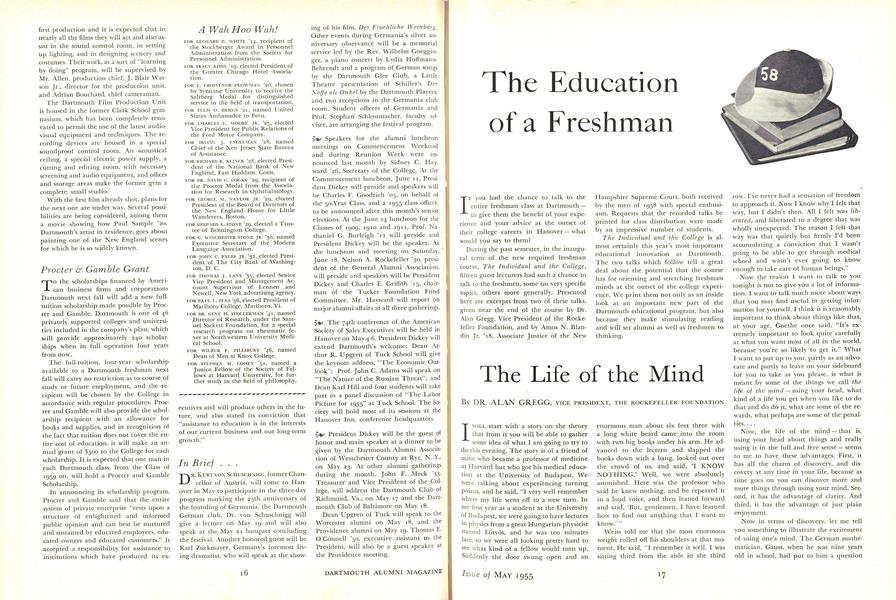

FeatureThe Education of a Freshman

May 1955 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

May 1955 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR

Features

-

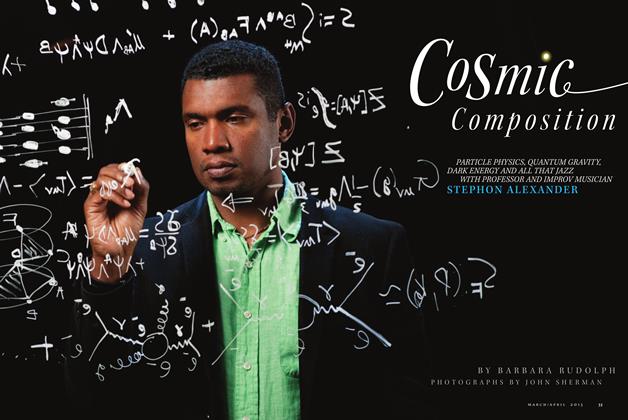

Cover Story

Cover StoryCosmic Composition

Mar/Apr 2013 By BARBARA RUDOLPH -

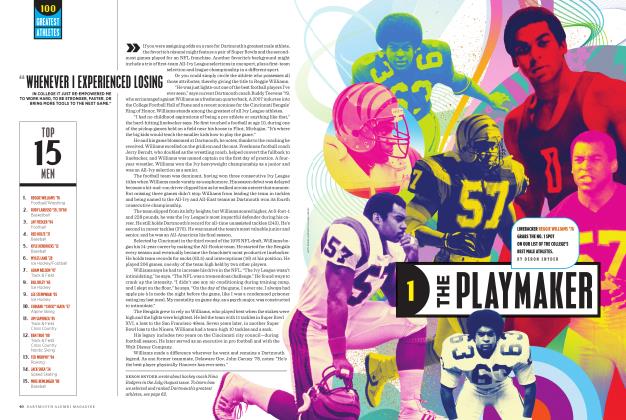

Features

FeaturesThe Playmaker

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 By DERON SNYDER -

Feature

FeatureAn Unease on Webster Avenue

APRIL 1978 By Mark Hansen -

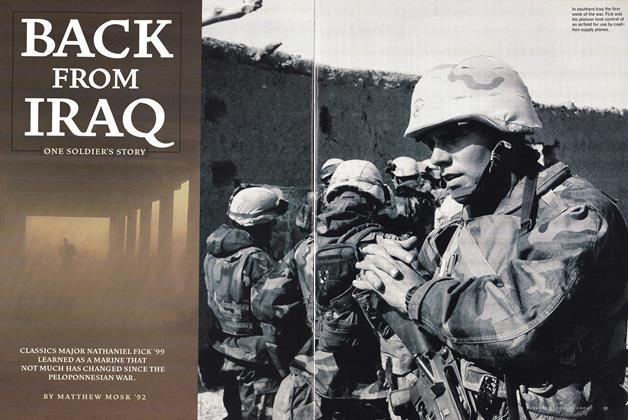

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack From Iraq

Jan/Feb 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureA Football Victory Hanover Will Never Forget

DECEMBER 1965 By R.B. -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2006 By Rodger Ewy '53, Rodger Ewy '53