ASSOCIATE JUSTICE, NEW HAMPSHIRE SUPREME COURT

GENTLEMEN, I am going to speak about your individual responsibility, which includes your social and every other kind of responsibility. The test to determine whether you are fulfilling your individual responsibility is to inquire whether you are exercising self-discipline, and horse sense. Upon whether or not you do depends ultimately your fun and your freedom.

Now, having spoken those two short sentences, I might about as well sit down, because I've told you everything - almost - that I know or have been able to learn in fifty-odd - some of them very odd- years. However, since I have made sort of a horse-trade with the College to go on here for approximately forty-five minutes, and since I have attended a number of other lectures and observed that some of you fellows confidently rely on that forty-five minutes to catch up on your sleep, I have decided not to let you down.

Speaking about sleepers, you know, as Dr. Gregg said here the other night, you sort of make little wagers, little bets, with yourself, and I have been greatly interested in trying to pick out what I would call my pet or prize sleeper. I thought I had the two leading candidates pretty well doped out. One of them usually drops off in about eleven minutes and twenty seconds, and the other one, his closest rival, goes off in about twelve minutes. I will say

though, to be fair to the fellow who takes twelve minutes, he sleeps more soundly. The eleven-minute-twenty-second man tosses and kicks a little bit, unlike his twelve-minute rival who always has to be punched by the fellow next to him who says, "Wake up, you dope, it's all over." I made a little bet with myself the other night and, by George, the one I picked crossed me up. He took twelve minutes to go to sleep and the other chap did it in eleven-forty! Let's see, it's about time . . .

Well, gentlemen, that brings me to the first point I want to bring up. I looked to my right, and you all looked the same way, but I was fooling you - the sleepers are over here to my left where you didn't look, and out of the tail of my eye I saw they were not asleep - yet. So the first point I want to bring up is: Don't be too easily misdirected. That is one of your first responsibilities. Not that you will be deliberately misdirected here at Dartmouth, you won't. This is probably as good a time as any to say that it will be a long while before you are again associated with as many essentially fine people who are trying to do the right thing by you as you have here on the faculty. I think I should add that I disagree with them on some subjects a hundred percent - raise that, make it two hundred - but that doesn't alter the fact that you are dealing with essentially fine people. However, you do listen to a lot of visiting firemen like myself, not only here but over in 105 Dartmouth. Words will pour over you in the next four years like the Niagara Falls cataract over a June bug, and you'll get just about as much good out of it unless you really want it to mean something.

Now let me give you, if I may, two examples of direction and misdirection. I am going to describe the two men from whom they came and let you fellows guess which one gave me the direction and which one the misdirection. And I may say now that I hope you will forgive me if a lot of these incidents I give you are personal incidents, because after all the things we know best are the things that have happened to us, not something that happened to Joe Doakes out in Saskatchewan.

These two men were professors, one at Dartmouth College, one at Harvard Law School. From one I received the most valuable, I think, or at least one of the two or three most valuable ideas I ever got anywhere, any time. From the other I received - bunkum. They both were fine, sincere men. I'll describe them and probably you fellows will guess from which one I got the bunkum and from which one the truth.

The Dartmouth professor, who taught Romance languages and was a very fine, kind man, would come to class with a pair of pants on - which you would expect, naturally - but what you wouldn't expect was the fact that he sometimes wore two vests, neither of which matched the other or the pants, and a coat that matched neither vests nor pants. He was a little bit absent-minded, and so am I. The Harvard Law School professor, on the other hand, was brisk and a great authority in his line - I still use him. He was right on the ball, as you would say, and obviously knew what he was talking about.

Now some of you have probably already guessed it: the nonsense came from the Harvard Law School professor - that's the truth - and the single most valuable idea I ever got was from the absent-minded Dartmouth professor of Romance languages. So you can never tell where the wheat is going to come from and where the chaff is coming from. Not that I didn't get many things of value from the Law School professor - I did, of course. But this particular thing, which made a great impression on me, was just plain bunkum. I'll tell you what it was and let you judge Whether it was bunkum or not. He said in very positive tones, and he backed it up with a beautiful argument that I couldn't answer at the time, having had no experience with which to answer it - he said, "Punishment does not deter crime." "Gee," I said to myself, "I guess we've been on the wrong foot here all along. This fellow teaches criminal law, he must know all about criminals." He had a massive araument, and I swallowed it.

I am not going to argue that point with you. I am just going to give you fellows two examples and let you answer it for yourselves. Suppose that, with the aid possibly of your mother or sister or brother, or maybe on your own, you wheedle your old man into letting you have a car next year, as some of you hope to do. Perhaps you've made progress already. But suppose you do, and he says, "0.K., you have this car, but you behave yourself. The first mess you get in, back comes the car." Now this is very unlikely, and I know you wouldn't for one minute be doing it, but just let's assume that you are blasting down the road toward Smith or Wellesley or Mt. Holyoke or Colby Junior, sixty-five miles an hour in a thirty-miles-an-hour zone. And suddenly the fellow beside you says, "Hey, watch it! State trooper!" Do you slow up, or do you speed up, and why?

Let's suppose another case, gentlemen, even more unlikely, and again I'll ask you to answer it yourselves. Let's assume a nice, balmy winter night - something like the one we've got outside - and you have a girl up here from someplace. This is next year, and it's after hours, and you're pretty cold walking around town, and you think maybe you'll take a chance - there's a nice fire in your fraternity house or in the lounge or somewhere else. Even though it's after hours you think you'll take a chance and go in there with the young lady, and you look around just as you re turning to go in, and you see the tall, dignified, commanding and distinguished form of Dean McDonald bearing down on you. Now you can answer this one. Do you say, "Hi, Dean, here we go!" or do you say, "Well, uh, um, cold night, Dean McDonald; uh, Sally and I are just going up to the Bema"? You fellows answer that one for yourselves too.

Punishment doesn't deter crimed of course it doesn't prevent all crime, but it helps. The only trouble with that seemingly revolutionary idea, beautifully argued out by the able Law School professor, is that it is bunkum, but I was a sucker for it at the time because of inexperience.

Now I'll tell you what I got from the professor of Romance languages - one of the two or three most practically valuable things that ever came to me as a trial lawyer or as a judge. It was in French 12 and the professor spoke about some old French philosopher who said, "To understand everything is to forgive everything." Well, that isn't quite literally true, but the idea back of it is to try to understand, tryto understand, the other fellow's point of view....

Now speaking of being fair to people, you know the Greek adage, Gnothisaftón. Of course you grasp what that means. What? You don't? Well, I'll tell you, neither did I, so I had a Greek friend translate it for me. It means Knowthyself. One of your most important responsibilities is to get to know yourself- not that you ever will completely. I said to my Greek friend, "How do you say, 'Don't kid thyself?" She replied, "In Greek we don't have any saying for that; we don't believe in wasting words." I said, "What do you mean, not wasting words?" "Well," she said, "if thee knows thyself, thee cannot kid thyself!" Greek logic, you cannot beat it

So find out which things work with yourself and which don't. And don't have too many illusions. For example, do I for one moment think of myself as a mature, unprejudiced person? Good Lord, no! I have as many prejudices as a hedgehog has quills, and I wage a ceaseless and not always winning battle against them. So will you. The main thing is to wage the battle. And one way to do it is to know thyself. Find out about thyself - and thyself is a queer bird in some ways. But that doesn't mean that thee is any queerer than me. Not a bit. And it's nothing to worry about, so long as you keep up the fight to try to know and understand yourself. But don't think for one minute that a liberal arts college, the best liberal arts college in the world, will do anything for you along that line. There's where I may disagree with some of my friends, but I think it depends entirely on you.

Some years ago I was holding court in one of the more heavily timbered sections of the state, and I always liked to hold it there, because there are a lot of pretty independent old thinkers to whom neither The New York Times nor the ChicagoTribune is the Bible. They do their own thinking and, believe me, it's pretty good thinking. One of the old chaps had a grandson in college, a liberal arts college and a good one - not Dartmouth, but a good one - and we stopped to get some gasoline from the old gentleman one morning, and I said, "George, how's your grandson making out?" "Well," the old man replied, "if he don't git no real set-backs, he'll come out in June a fust-class damn fool!" What did he mean by that? Well, I know what he meant by it. He meant that the boy had simply exchanged one set of prejudices for another. That's all - just one set for another. A boy may come into college a financial or social snob and go out an intellectual snob, which is a little the worst of the three - although they're all bad enough, the Lord knows. So don't think that the best liberal arts college in the world is going to do one thing for you unless you've got it in you to do it yourself. Sometimes I think some people are born with it, and some people are born without it but with the desire to acquire it. You've got to have at least the desire to acquire it. If you haven't, you are out of luck....

THERE is an old Roman saying, "Go willingly with the Fates, or be dragged." It isn't much fun to be dragged. Now the Fates are demanding responsibility and if you don't exercise it yourself someone will do it for you. In every place, you'll notice, where freedom has gone, it's because individuals haven't shouldered their individual burdens. But your first duties are to find out about yourself, discipline yourself, know yourself. You'll get to know others through knowing yourself. Tolstoi says somewhere that the man who knows one woman well knows more about women than the man who knows thousands, and Tolstoi, according to his own confessions, was qualified to pass on the subject. Well, you are never going to help anybody else until you have gotten yourself straightened out first. You'll find that quite a job. But go to it. That's one of the reasons you are here. This idea of reforming the world is just bosh until you can reform yourself — just a waste of time. As a wise man put it thousands of years ago, the peace of the world depends on ordering the national life, ordering the national life depends on ordering the home life, and ordering the home life depends on ordering the individual life. It's as simple as that, and yet it's the toughest thing in the world at the same time....

There is not much more that I need to say to you gentlemen. You know what you ought to do Here just as well as I do, and maybe better. You know what is expected of you. What there is inside a man that gets him to do the right things, I don't know. I think with all of us there's a little switchboard, way down deep, and until you touch that switchboard, you're just - talking. (I wonder how my sleeper is coming.) But once you do get at it, you're getting somewhere.

This is a great place to be. All of us who have been here have pretty nice recollections of it. You fellows will be coming back here for years afterward, hard-headed people some of you, but you will be more than a little bit sentimental about this place. The memories you carry away from here will be of strange things - they won't be of these so-called important events at all. They will be odd little recollections that you'll carry away. Whatever you touch here and whatever touches you becomes part of you forever, for good or for evil. The great religious teachers have always known that, and modern scientists are beginning to get on to it. Everything that touches you, no matter how slight it is - it may lie down deep in your subconscious or it may be boiling right up at the surface - but it's there always.

Perhaps the idea that I wish to bring out can best be expressed by reciting, a little poem which I suspect a fellow wrote to his girl - fellows have been known to do that. It's anonymous, so I never had a chance to ask the author whether he did or whether he didn't. It goes like this:

Where is the haze that veiled October hills so long ago?

Where are the waters of the stream that wound so slow They held the flaming trees, the hills, the sky, That idle on their surface seem to lie, And wait for us alone to come to see And wonder that such loveliness could be?

Where is the little wind that blew so long ago? Where did it come from? Where did it go? Where is your look, your laugh, of sheer delight,

The things we thought and did that autumn night?

Gone with the snows of yesteryear, you say? Gone like the dawn of some forgotten day?

Time must at long last from us all things

sever?

No! They are ours and part of us forever.

So, from your years in Hanover, I wish there may touch and become a part of you, dawns and dusks, the flame of autumn hills and the winter moon over Dartmouth Row. I wish you, too, days and nights of fellowship, so that forever after you leave here you will look forward eagerly to the all-too-rare occasions when you are to see again old Jim, or Tom, or Joe. May you have, too, memories of houseparties, with no harm done yourself or others, and of a pretty girl; you will not forget her ways or her laughter, or even the scent of the perfume she wore. And the strange thing to me is that your memory of such will be fresh and green years after you have gone from the Hanover Plain and when all recollection of the pompous words and events which sometimes surround you has vanished into the oblivion of a night from whence it shall never return. But more than anything else, gentlemen, I hope there becomes a part of you the abiding conviction that your freedom and your individual responsibility are one and that you so act upon this conviction that you and they shall live!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEVEN DISAGREEING WITH HIM WAS PLEASANT

May 1955 By ARTHUR H. LORD '10 -

Feature

FeatureThe Life of the Mind

May 1955 By DR. ALAN GREGG, -

Feature

FeatureThe Education of a Freshman

May 1955 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

May 1955 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR

Features

-

Feature

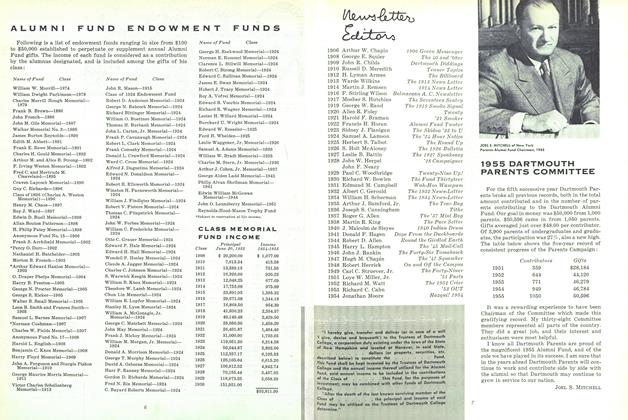

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

December 1955 -

Feature

FeatureUnderstatement: A Busy Summer

OCTOBER 1966 -

Feature

FeatureClass Notes

September | October 2013 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

Feature

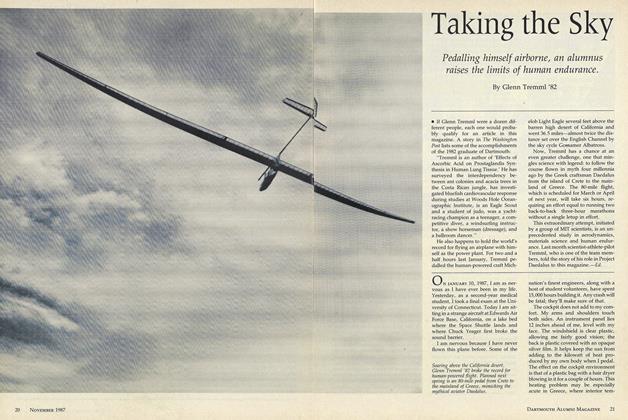

FeatureTaking the Sky

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Glenn Tremml '82 -

Feature

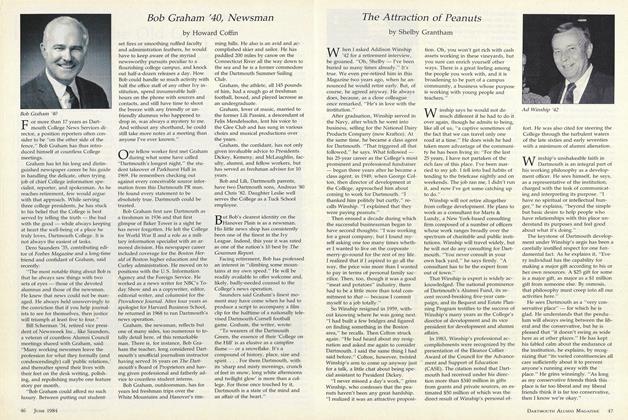

FeatureBob Graham '40, Newsman

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Howard Coffin -

Feature

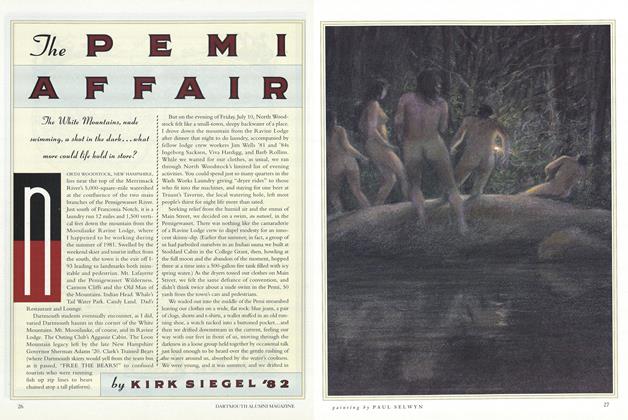

FeatureTHE PEMI AFFAIR

June 1993 By KIRK SIEGEL'82