By Herrymon Maurer '35. NewYork: Macmillan, 1955. 303 pp. $5.00.

It is a difficult task to portray the changing nature of the modern large business corporation. It is even more difficult to assess its future place. Nevertheless, Herrymon Maurer, Fortune writer and business analyst, gives us better perspective for judgment in GreatEnterprise.

The author states that his book aims to suggest what the large corporation is and where it may be going. At the very outset he describes the giant corporation as a social wonder - a vast sprawling unmeasurable force not unlike the sea. Few of his readers will take issue with him on this point. But where the giant corporation may be going is quite another matter. Especially is this disturbing when one ponders over the needed post-war managerial reorganizations undertaken by great corporations like General Electric Ford Motor Company, and the New York Central. It is to be hoped that managerial skills and judgment, via committees or otherwise, will grow pari passu with corporate size.

Since the Great Depression of the thirties the tide seems to be running strongly towards more responsible social behavior on the part of the great corporations. This is all to the good whatever may be the reasons. On the other hand there appears to be some reversion to the tactics of the nineteen twenties. Maurer warns that a quiescent public opinion should not be misjudged. Enterprising financial manipulators may find that they are playing with a smoldering fire capable of being fanned to a fierce blaze.

The author writes in a manner not unlike that of the late Frederick Lewis Allen. In broad sweeps he pushes aside details to give a splendid picture of the changing nature o£ the corporation. He admires this legal creature which has so greatly improved contemporary economic life. At the same time he sees in it a force of evil not unlike that of an overbearing state. Both can become the agents of over-rationalization of life, purveyors of dull conformity, and eradicators of individual freedom.

He agrees with Peter Drucker that this is the age of group management. But management to be successful in the long pull must be highly imaginative. It should guard against becoming the agency of conformity.

The big problem of management is to develop a rationale of great enterprise by which the large corporation may be explained m terms of its intertwined economic activities and its social responsibilities. If management can do this wisely and well then, indeed, the large American corporation will rest happy and accepted at home. And if it broadens its horizons, it may gain friends and followers abroad. Like Adolph A. Berle Jr., Mr. Maurer sees the great worth of the corporation, yet he is not unmindful of the dangers of its perversion.

Readers will find in Great Enterprise a modern and friendly view of a number of America's leading corporations and corporate leaders. Big business has been "whipping boy' for a long time. The presence of more friends in court may lead to a truer assessment of its real worth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

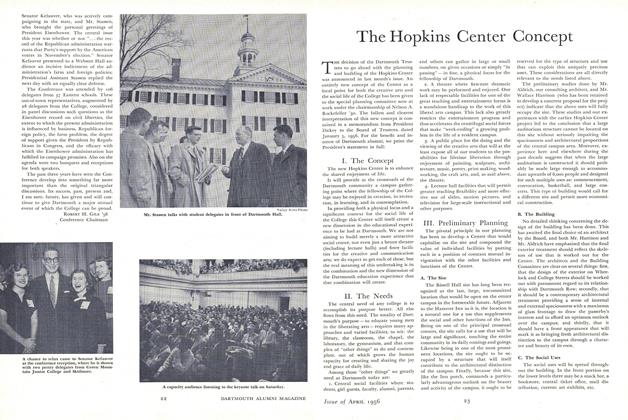

FeatureThe Hopkins Center Concept

April 1956 -

Feature

FeatureTHE MOCK-DUEL MURDER

April 1956 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

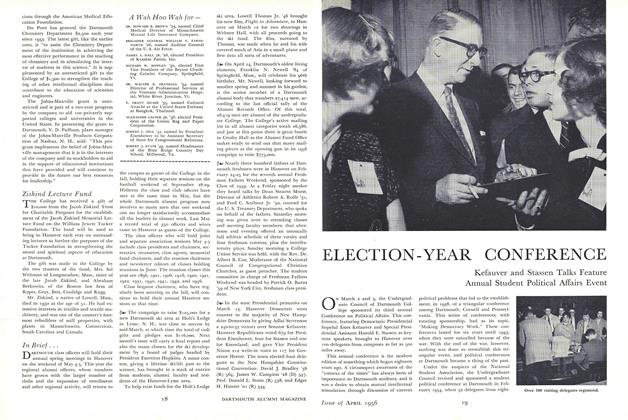

FeatureELECTION-YEAR CONFERENCE

April 1956 By ROBERT H. GILE '56 -

Feature

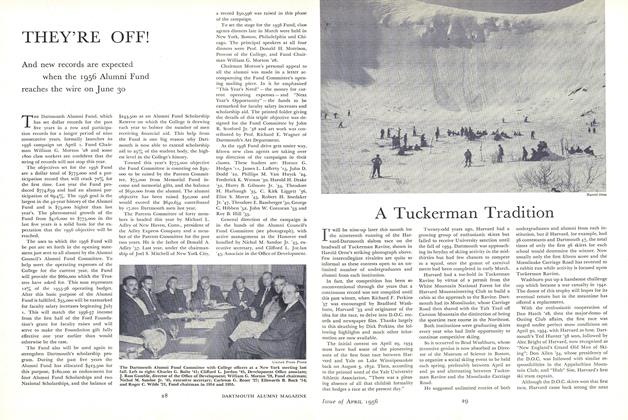

FeatureA Tuckerman Tradition

April 1956 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1956 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN, JOHN W. MOXON

WILLIAM A. CARTER

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By William A. Carter -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

FEBRUARY 1971 By WILLIAM A. CARTER, ALBERT W. FREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

NOVEMBER 1971 By WILLIAM A. CARTER, ALBERT W. FREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

OCTOBER 1972 By WILLIAM A. CARTER, ALBERT W. FREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

NOVEMBER 1972 By WILLIAM A. CARTER, ALBERT W. FREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

DECEMBER 1972 By WILLIAM A. CARTER, ALBERT W. FREY

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

NOVEMBER 1967 -

BOOKS

BOOKSEditor’s Picks

MAY | JUNE 2019 -

Books

BooksELEMENTARY COLLEGE PHYSICS

May 1937 By G. F. Hull -

Books

BooksIMPLEMENTATION

November 1973 By JAMES COMPTON WICKER '21 -

Books

BooksTHE UNITED NATIONS IN ACTION

March 1951 By JOHN G. GAZLEY -

Books

BooksGREAT MYSTERIES OF HISTORY.

DECEMBER 1971 By JOHN HURD '21