THE Class of 1879 was no slouch when it came to contributing to the traditions of the College. It invented the Wah-hoo-wah cheer, introduced senior canes, planted the first class tree, and started Wet Down. Story has it that the earliest Wet Downs were celebrated in the Wheelock tradition. By our time, somebody furnished a keg of lemonade in the center of the campus, but this bibulous feature, publicly at least, has now diminished into a symbolic pushing of tongue into cheek. What remains, and properly, is the induction of Palaeopitus (the typesetter's bogie), the running of the gauntlet, and the presentation of awards. The gauntlet is a unique relic (if the Walter Humphrey murals and the Baker weathervane are excepted) of our aboriginal origins. Traditionally each class runs between a double line of its seniors till finally the new Palaeopitus members go the whole course - a line reaching from here to eternity, or at least to the White Church. But possibly the physical beating is recompensed by the spiritual uplift as the student body, lemonadeless, reconvenes on the campus for the "awards."

First, the symbolic presentation of the Senior Fence to the junior class now a gift by non-possessors to noncravers. Then comes a series of honorary individual presentations that have, we still fondly hope, a significance. There is a whole heap of charms for the dormitory and fraternity winners of a plethora of intramural competitions in everything from canasta to inching. There follow the recognitions, predetermined by democratic or semidemocratic decision, of excellence in athletic or general existence, the most important being the Barrett Cup for Ail-Round Achievement. But there are, in addition, better than a dozen other nods to those who have proven their value in general merit or in specific contribution to any of a dozen different sports. All together there are six cups, three medals, two plaques, two sets of books, $60, and a year's subscription to The New York Times.

Academic awards are usually made in camera, or in the Bursar's office. Scholarly distinction is recognized in ten or more disciplines by over forty different prizes. One cup and one award of books are included, but the bulk is in good hard cash to a total of $2275. Recipients are picked by the different departments of the faculty and, here again, there is a scattering of the largesse, it being a rare student indeed who can demonstrate simultaneous excellence in oratory, composition, ancient and modern languages, science, history, and philosophy. But honor rather than profit is the motive, for even if such an intellectual decathlon type should sweep the field, and were to cut his own hair and display frugality in other ways, it seems scarcely credible that he could subsist entirely on the fruit of his wits - as do those who haunt give-away programs or dwell in department stores or subways.

All these benefits are apart from the very considerable (at least to us 450 G's is nearer lettuce than hay) financial aid program that the College administers annually. There are some fifty National Scholarship awards and about thirty on a regional basis, but the great majority are just plain old scholarships, with no strings attached. There is, however, buried in the fine print in the middle of the catalogue, a listing of well over a hundred separate scholarship funds tied to the predilections of their donors. Preferential treatment is to be given potential recipients on the basis of heritage, geographical location, academic proclivities, or personal habits. Most of these funds are small, but it has occurred to us that one might be eligible for a very tidy sum by combining a number of different qualifications. The best deal we have been able to work out would be for an Indian, descended from a Phi Delt or Tri Kap (or both), of the Class of 1877, who had been in the foreign service of the State Department. If our candidate were also a native of New Hampshire and had lived in New Jersey, so much the better. He really could make a killing by adding to his virtues a diploma from the Eastport (Maine) high school and another from Exeter, and by eschewing liquor and tobacco. But all this would demand a certain amount of contrivance and perhaps it would be simpler, if less ambitious, to plump for the modest award earmarked "for a religious man from Missouri."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Reynold Scholars

June 1956 By PROF. JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureLEARN AMERICAN

June 1956 By EDWARD C. KIRKLAND '16 -

Feature

FeatureA NEW CONCEPT of Dormitory Living

June 1956 -

Feature

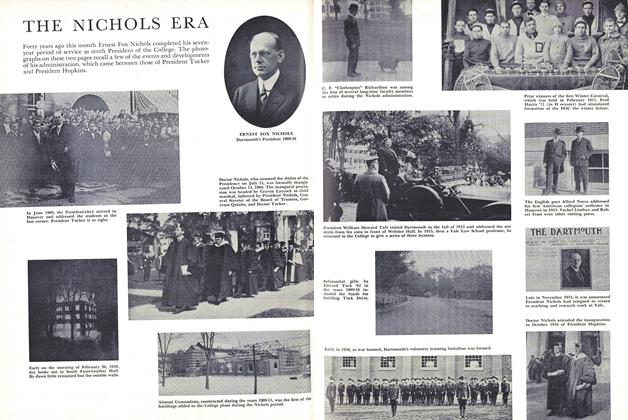

FeatureTHE NICHOLS ERA

June 1956 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

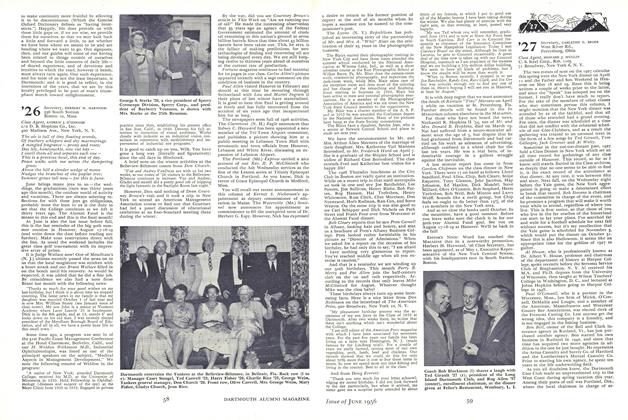

Class Notes1926

June 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR

BILL McCARTER '19

-

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago .... Direful Days

March 1934 By Bill McCarter '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

June 1954 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

March 1955 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

May 1955 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

MAY 1957 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleTHE HANOVER SCENE

MAY 1959 By BILL McCARTER '19