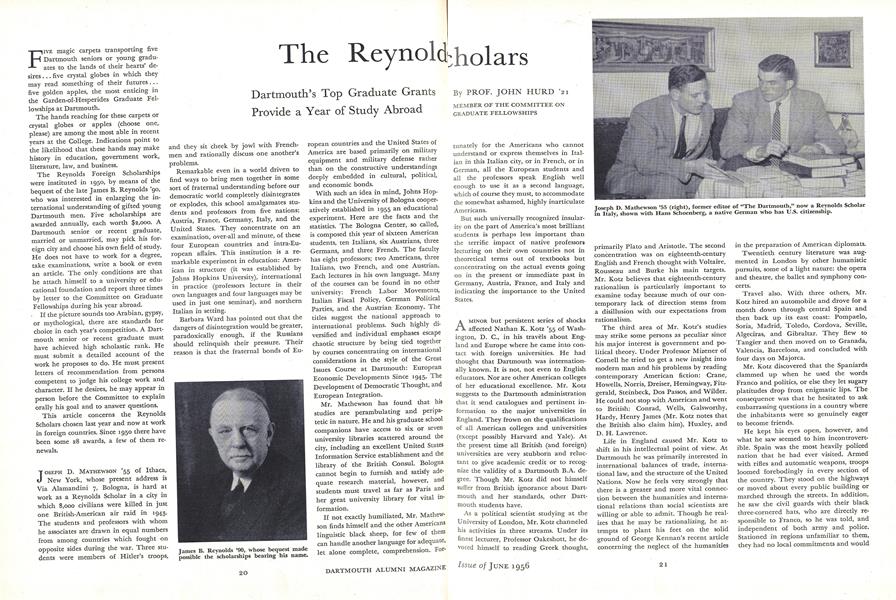

Dartmouth's Top Graduate Grants Provide a Year of Study Abroad MEMBER OF THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE FELLOWSHIPS

FIVE magic carpets transporting five Dartmouth seniors or young graduates to the lands of their hearts' desires ... five crystal globes in which they may read something of their futures ... five golden apples, the most enticing in the Garden-of-Hesperides Graduate Fellowships at Dartmouth.

The hands reaching for these carpets or crystal globes or apples (choose one, please) are among the most able in recent years at the College. Indications point to the likelihood that these hands may make history in education, government work, literature, law, and business.

The Reynolds Foreign Scholarships were instituted in 1950, by means of the bequest of the late James B. Reynolds '90, who was interested in enlarging the international understanding of gifted young Dartmouth men. Five scholarships are awarded annually, each worth $2,000. A Dartmouth senior or recent graduate, married or unmarried, may pick his foreign city and choose his own field of study. He does not have to work for a degree, take examinations, write a book or even an article. The only conditions are that he attach himself to a university or educational foundation and report three times by letter to the Committee on Graduate Fellowships during his year abroad.

If the picture sounds too Arabian, gypsy, or mythological, there are standards for choice in each year's competition. A Dartmouth senior or recent graduate must have achieved high scholastic rank. He must submit a detailed account of the work he proposes to do. He must present letters of recommendation from persons competent to judge his college work and character. If he desires, he may appear in person before the Committee to explain orally his goal and to answer questions.

This article concerns the Reynolds Scholars chosen last year and now at work in foreign countries. Since 1950 there have been some 28 awards, a few of them renewals.

JOSEPH D. MATHEWSON '55 of Ithaca, New York, whose present address is Via Alamandini 7, Bologna, is hard at work as a Reynolds Scholar in a city in which 8,000 civilians were killed in just one British-American air raid in 1943. The students and professors with whom he associates are drawn in equal numbers from among countries which fought on opposite sides during the war. Three students were members of Hitler's troops, and they sit cheek by jowl with Frenchmen and rationally discuss one another's problems.

Remarkable even in a world driven to find ways to bring men together in some sort of fraternal understanding before our democratic world completely disintegrates or explodes, this school amalgamates students and professors from five nations: Austria, France, Germany, Italy, and the United States. They concentrate on an examination, over-all and minute, of these four European countries and intra-European affairs. This institution is a remarkable experiment in education: American in structure (it was established by Johns Hopkins University), international in practice (professors lecture in their own languages and four languages may be used in just one seminar), and northern Italian in setting.

Barbara Ward has pointed out that the dangers of disintegration would be greater, paradoxically enough, if the Russians should relinquish their pressure. Their reason is that the fraternal bonds of European countries and the United States of America are based primarily on military equipment and military defense rather than on the constructive understandings deeply embedded in cultural, political, and economic bonds.

With such an idea in mind, Johns Hopkins and the University of Bologna cooperatively established in 1955 an educational experiment. Here are the facts and the statistics. The Bologna Center, so called, is composed this year of sixteen American students, ten Italians, six Austrians, three Germans, and three French. The faculty has eight professors; two Americans, three Italians, two French, and one Austrian. Each lectures in his own language. Many of the courses can be found in no other university: French Labor Movements, Italian Fiscal Policy, German Political Parties, and the Austrian Economy. The titles suggest the national approach to international problems. Such highly diversified and individual emphases escape chaotic structure by being tied together by courses concentrating on international considerations in the style of the Great Issues Course at Dartmouth: European Economic Developments Since 1945, The Development of Democratic Thought, and European Integration.

Mr. Mathewson has found that his studies are perambulating and peripatetic in nature. He and his graduate school companions have access to six or seven university libraries scattered around the city, including an excellent United States Information Service establishment and the library of the British Consul. Bologna cannot begin to furnish and satisfy adequate research material, however, and students must travel as far as Paris and her great university library for vital information.

If not exactly humiliated, Mr. Mathewson finds himself and the other Americans linguistic black sheep, for few of them can handle another language for adequate, let alone complete, comprehension. Fortunately for the Americans who cannot understand or express themselves in Italian in this Italian city, or in French, or in German, all the European students and all the professors speak English well enough to use it as a second language, which of course they must, to accommodate the somewhat ashamed, highly inarticulate Americans.

But such universally recognized insularity on the part of America's most brilliant students is perhaps less important than the terrific impact of native professors lecturing on their own countries not in theoretical terms out of textbooks but concentrating on the actual events going on in the present or immediate past in Germany, Austria, France, and Italy and indicating the importance to the United States.

A MINOR but persistent series of shocks affected Nathan K. Kotz '55 of Washington, D. C., in his travels about England and Europe where he came into contact with foreign universities. He had thought that Dartmouth was internationally known. It is not, not even to English educators. Nor are other American colleges of her educational excellence. Mr. Kotz suggests to the Dartmouth administration that it send catalogues and pertinent information to the major universities in England. They frown on the qualifications of all American colleges and universities (except possibly Harvard and Yale). At the present time all British (and foreign) universities are very stubborn and reluctant to give academic credit or to recognize the validity of a Dartmouth B.A. degree. Though Mr. Kotz did not himself suffer from British ignorance about Dartmouth and her standards, other Dartmouth students have.

As a political scientist studying at the University of London, Mr. Kotz channeled his activities in three streams. Under its finest lecturer, Professor Oakeshott, he devoted himself to reading Greek thought, primarily Plato and Aristotle. The second concentration was on eighteenth-century English and French thought with Voltaire, Rousseau and Burke his main targets. Mr. Kotz believes that eighteenth-century rationalism is particularly important to examine today because much of our contemporary lack of direction stems from a disillusion with our expectations from rationalism.

The third area of Mr. Kotz's studies may strike some persons as peculiar since his major interest is government and political theory. Under Professor Mizener of Cornell he tried to get a new insight into modern man and his problems by reading contemporary American fiction: Crane, Howells, Norris, Dreiser, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Steinbeck, Dos Passos, and Wilder. He could not stop with American and went to British: Conrad, Wells, Galsworthy, Hardy, Henry James (Mr. Kotz notes that the British also claim him), Huxley, and D. H. Lawrence.

Life in England caused Mr. Kotz to shift in his intellectual point of view. At Dartmouth he was primarily interested in international balances of trade, international law, and the structure of the United Nations. Now he feels very strongly that there is a greater and more vital connection between the humanities and international relations than social scientists are willing or able to admit. Though he realizes that he may be rationalizing, he attempts to plant his feet on the solid ground of George Kennan's recent article concerning the neglect of the humanities in the preparation of American diplomats.

Twentieth century literature was augmented in London by other humanistic pursuits, some of a light nature: the opera and theatre, the ballet and symphony concerts.

Travel also. With three others, Mr. Kotz hired an automobile and drove for a month down through central Spain and then back up its east coast: Pompaelo, Soria, Madrid, Toledo, Cordova, Seville, Algeciras, and Gibraltar. They flew to Tangier and then moved on to Granada, Valencia, Barcelona, and concluded with four days on Majorca.

Mr. Kotz discovered that the Spaniards clammed up when he used the "words Franco and politics, or else they let sugary platitudes drop from enigmatic lips. The consequence was that he hesitated to ask embarrassing questions in a country where the inhabitants were so genuinely eager to become friends.

He kept his eyes open, however, and what he saw seemed to him incontrovertible. Spain was the most heavily policed nation that he had ever visited. Armed with rifles and automatic weapons, troops loomed forebodingly in every section of the country. They stood on the highways or moved about every public building or marched through the streets. In addition, he saw the civil guards with their black three-cornered hats, who are directly responsible to Franco, so he was told, and independent of both army and police. Stationed in regions unfamiliar to them, they had no local commitments and would be instantly and ruthlessly ready to suppress any possible uprisings.

Spanish official altitudes towards the United States were most cordial as shown by newspapers, radio, newsreels, and the attitude of the police, who have been obviously instructed to bend over backwards to be nice to all Americans. American servicemen were allowed to wear their uniforms in public, a practice which Franco had strenuously forbidden.

LET us assume that a young Dartmouth graduate wants simultaneously to study American and British architecture, to compare notes on new building, both office and domestic, to meet the leading architects in actual practice in London, and incidentally to travel on the Continent. There is such a man: Frederick A. Stahl '52 of Danbury, Conn., who is now living at 20 Queensgate, London, S. W. 7.

As a Reynolds Scholar, Mr. Stahl worked in close collaboration with the students and staff at the Polytechnic School of Architecture, a tremendously stimulating experience, for he has always had a very keen interest in teaching architecture, now reinforced by his new life in England.

The work of Mr. Stahl and his associates was concerned primarily with a particular application of research to the design of buildings in an attempt to secure a rational organization of building units which in the future may be prefabricated or preassembled largely in factories rather than on sites. Naturally enough, studies branched out to range over the entire field of design, all the way from large-scale planning of groups of buildings to the detailed analyses of small-scale units.

The question any Dartmouth graduate might well ask Mr. Stahl first is: "On the basis of your year in England what would you say is the architectural climate in Great Britain?"

Mr. Stahl's reply might run something like this: At the present time architecture in Great Britain is in an important period of change, a shift more or less gradual from emergency conditions following the devastations caused by German bombs. Only within the last two years have governmental controls and priority systems been completely relaxed. The effects of a long period of restraint have been slow in wearing off.

England is faced with many grave problems calling for great efforts from the architectural profession. Among these, housing and schools have been most pressing, and British architects have dealt with them over the past ten years with a high degree of skill and imagination.

Although not yet on a pre-war scale, public and private building is now becoming possible, and architects are beginning to feel their way into a more ample expression. The potential for this new expression is great, with the experience developed during the large-scale public housing and schools programs continuing still at even greater volume. In addition, a numerous and vital group of young architects are beginning to undertake new problems.

If Mr. Stahl was eager to meet them, they were equally eager to meet him, for in all this activity England looks very much to America for example and inspiration. It was pleasant to learn that much of the best American work of the last few years is well known in Great Britain liked, and admired. Especially in the fields of design from which British architects have been by necessity excluded, the vital force of American ideals has been great.

The longer Mr. Stahl resided in London, the more he became convinced that this situation served to bring into sharper focus the ever-growing need of the interchange of ideas and communication between Great Britain and the United States. In a letter he has written happily that in this respect he found his more rewarding and most exciting fulfillments in his association with British architects and students of architecture.

These associations have been more than businesslike and formal. Mr. Stahl was fortunate enough to meet and make lasting friendship with members of his profession, to spend long hours with them discussing mutual problems, and to work with them at close range in the same sort of intimate give-and-take as he would with his countrymen at home.

If such an attitude suggests that because Great Britain and the United States speak a more or less common language, we are necessarily "brothers under the skin" and "natural allies," Mr. Stahl issues a word of warning. He has become increasingly aware that England is even more a foreign country than some with different languages separating them from America. England, he says, must be approached on her own grounds rather than on ours, unconsciously transposed. This process of living England in England, of seeing England with English eyes, of working in England under English conditions, of testing English standards by English measurements was especially important to Mr. Stahl, who became more and more conscious that previously assumed parallels between England and American life were false and that important English-American differences were by no means obvious to casual observers.

It may not seem peculiar that Mr. Stahl has come to their point of view when one considers how unlike an American tourist he has been in his activities. Under the direction of William Allen, Director of Architectural Research, Building Research Station, Garston, Watford, Herts, (about twenty miles north of London), he made the rounds of various research departments and began his studies in the refinement and amplification of methods and standards in lighting based upon methods of calculation and research undertaken by the Station. He made visits to local and county council architects about actual work involving the development of new methods or devices for the calculation and the revision of existing standards.

Still another activity involving Mr. Stahl's energies was in the field of modular coordination, which is concerned with the rational organization of sizes of buildings components throughout the building industry. At present the Building Research Station with which he is associated is engaged in an international program of research involving most of the Western European nations under the sponsorship of EPA. The hope is that this work will eventually produce a system relating the elements of construction throughout Europe and enabling much greater flexibility in design, construction, and trade.

IT may not be true that when good Americans die they go to Paris to spend an eternity of bliss, the exact nature of which is not defined; but it may be true that an outstanding Dartmouth senior like Martin B. Friedman '55 of Hewlett, New York, may devote himself so well to his undergraduate studies and dream Paris so concentratedly during his life in Hanover that he will be awarded a Reynolds for study in Paris. A one-year delay may even be beneficial for an aspirant for a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature at Yale and an eventual instructorship in an American college or university.

The academic adventures of Mr. Friedman may indicate what might well happen, with certain variations, to any ambitious and gifted young man of 23 immersing himself in the radiance of that city of light and in the Sorbonne. Mr. Friedman headed straight for the Fondation desEtats-Unis where he could enjoy the benefits of meals for only twenty cents and certain American luxuries. There he discovered to his dismay that he could speak hardly any French, for everyone preferred English, and that he spent too much time in commuting to and from the university. A little astute investigation enabled him to find back of the Chamber of Deputies a French family which did not want to practise its English. The father, a newspaperman associated with Le Monde, was a specialist in Spanish affairs. Two sons, aged 18 and 12, provided the vernacular flow of teen-agers, and Madame the Mother one meal on a demi-pension plan which enabled Mr. Friedman to roam the city for conversational excitements of a sort different from domestic in the million and one restaurants and cafes which help to make Paris the city it is.

The university was of course Mr. Friedman's main interest. In the beginning he took an initiating course at the so-called Advanced School for the Instruction of Foreign Professors of French. In the Course in French Civilization he listened to lectures by French authorities: Aspects of France, French Newspapers and Their Problems, Religion and Free Thought in France, French Universities and Scientific Research, French Economics, and Introduction to French Politics. Essentially this course is the one given under different auspices to Fulbright students.

In addition to the three hours and a half of lectures each morning, Mr. Friedman attended three afternoons a week a practical Works Course consisting of intensive training in grammar, composition, and writing idiomatic French under pressure.

Later on in the year he attended lectures by the most distinguished professors in France on French literature in the Middle Ages, the 17th, and 18th centuries and on French history. He found them excellent because they combined the benefits of a general consideration of a writer (i.e. the historical, biographical and bibliographical information) and of penetrating analyses of his works. This second aspect of the course was supplemented by training sessions in which sections of twenty students discussed under the leadership of a teacher particular texts. For these afternoon classes each person prepared regular written assignments which were corrected carefully to enable him to face later final examinations.

Dartmouth seniors and young Dartmouth graduates may be interested to know that even if Mr. Friedman passes these examinations, Yale University will probably not give him credit for an advanced degree. The reason is that the courses are too general though Mr. Friedman is going ahead on his own personal investigations and on his concentration of the Classical Period, the theater, the novel, and the philosophy of the 1650's, 1660's, and 1670's. He must not only present a dissertation on this particular period at the Sorbonne but also pass examinations over the entire period of French literature. The degree to be awarded him is called an advanced degree of a departmental diploma.

To prepare himself for studies at the Yale Graduate School next year, Mr. Friedman has also been working on German and Latin in which he will be examined for reading ability.

Americans have such a hard time learning to speak foreign languages well that it is interesting to see how far Mr. Friedman has progressed after devoting every spare minute to French conversation with every kind of person. In a letter written January 21 he said that since his arrival in September (one must remember that he studied French at Dartmouth and had considerable conversational facility as a senior) he had improved so much that he was encouraged, although he was far from the point of speaking French unhesitatingly. He still noticed to his dismay that he caught himself translating his thoughts, but more and more often he was achieving a natural spontaneity and native idiom. Though he can read French almost as effortlessly as English, he can write French only with laborious effort because, understandably, he has had the least practice in that form of communication.

BEFORE settling down at 17 Horday Hasirah, Katamon, Jerusalem, Israel, Marshall T. Meyer '52 of Norwich, Conn., travelled in England, Denmark, Sweden, Germany, Holland, Belgium, France, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Italy, Greece, and Turkey. His experiences could easily make a thick book with expansions on such themes as the English theater, Oxford with an afternoon at the Bodleian Library, the wonderful library at Copenhagen where he sat before the statue of Kierkegaard and thumbed through Fear and'Trembling (with no little bit of the title in his own bones), the castle of Elsinore of Hamlet fame, a good view of the havoc wrought by the war in Germany with its complex reaction of pity and "it served them right," the incredible poverty of Spain in which country the military is in great prominence, a good look at the dethroned monarchs of Europe who live in Estoril outside Lisbon, the awe one senses before Swiss mountains, the thrill of an audience with the Pope even for a Rabbinical student, the beauty of Venice where Marshall Meyer understood the winter yearning of Professor George C. Wood, the maze of the Istanbul bazaar, and then finally the supreme thrill of treading on the soil of Israel which is the cradle of Western religion.

The soil as soil was somewhat barren, and the country was somewhat impoverished. For Mr. and Mrs. Meyer, especially for Mrs. Meyer, life has been unluxurious to the point of pain. She obtained hot water only after two hours of kerosene heating and then only for a bath, not for dishes. Ovens were unheard of, and she cooked from a kerosene burner. Food was scarce and expensive. Meat cost $3.50 a pound and coffee even more. Compared with Jewish stores, Tanzi's is a super-colossal A & P. One hardly ever chose food; one took what stores offered. Menus were consequently simple.

But the Meyers looked on physical comforts as unimportant before the inspiring country of Israel. Mr. Meyer himself was so awed by the long centuries of history and Judaism that he hardly knew where to begin. Whether it be from a sociological, religious, economic, political or almost any other point of view, he passionately believes that this land demands great attention and even more understanding. The miracle of reclaiming what a few short years ago was a barren country, the growth of a young democratic state fraught with the tremendous problems of economy, security, and mass immigration, the constant border episodes claiming human life each night, the polyglot population containing almost every type from world-renowned scholars and scientists and doctors to poor, hungry, diseased, and aged Africans and Asians knowing nothing of modern standards of living and existing from day to day as if they were back in the tenth century all these dramatic and chaotic paradoxes make almost impossible adequate comment from an American sympathetic and fresh on the scene.

The most casual newspaper reader knows how steadily and dangerously the Near East situation degenerated, with war just around the corner, until Dag Hammarskjold, that indefatigable and mastermind of a U. N. Secretary General, in April managed to persuade Jews and Arabs to a truce fastened with cobweb threads and signed in water. Even as far back as October Mr. Meyer spoke of the political situation as "most alarming" with war so close that he doubted whether he would be able to finish the year and signed his name at the American Consulate which he hoped would give him proper instructions if the conflagration really skyrocketed. It grew steadily worse.

Chilled by this prospect and frozen by the weather (he sat in class all day in a heavy overcoat and with gloves on, and at night he often studied by candlelight so uncertain was electricity), Mr. Meyer carried on in a winter unusually fierce and rainy.

If the classrooms at the university were numbing to the body, heartbreaking and soul-searing was the view from the window overlooking Mount Scopus and the beautiful buildings of the University in Arab hands and unusable. Actually they still belonged to the Israelis and were even guarded by Israeli troops, but no access was granted. More than 700,000 volumes, the entire library, gathered dust on Mount Scopus while in the New City students by the hundreds waited to do an assignment in a book of which they had only one copy.

The faculty had countless manuscripts of their own work which they could not use or even see. The building was jammed from 8 in the morning until 10 at night, classes all the time, and one small reading room heated somewhat by kerosene burners. Lanterns hung in every room, and as soon as the lights went out, classes were held by candlelight.

The university is nevertheless on a very high level because the faculty is made up of scholars, great men, world-renowned in their fields, and because secondary education in Israel is far more intensive and challenging than in the United States. In proportion, few people go to the University, but those given the privilege are fine and serious students who must work hard to support themselves.

Mr. Meyer's own schedule was finally fixed as follows: (1) Ten hours of Talmuu a week in class. Homework enabling him to recite ran to 25 hours of concentrated preparation, much aided by books sent him by Richard W. Morin, Librarian, Baker Library. (2) Seven hours of Hebrew a week in class which included grammar, composition, Bible, literature, conversation, and newspaper reading. (3) Two hours a week in Zohar and the development of Kabbalah. (4) One hour a week on an introduction to the Mishnah and other Tannaitic Literature. (5) A bi-weekly seminar which met for three and a half hours on Religious Thought and Problems in Israel today.

In addition to this "official" study, Mr. Meyer tried also to avail himself of as many private meetings with scholars as possible. He has had two magnificent sessions with Martin Buber, each of great value and long enough, two and a half hours, for lasting benefit. Aged 78, Buber, born in Vienna, is the Jewish writer, philosopher, and scholar who has worked for the development of Hasidism and recognition of the cultural significance of Judaism.

As for the land itself and the social experiments, Mr. and Mrs. Meyer spent a number of "intensely interesting weekends" at various Kibbutzim and children's villages, and they have visited "Mabarrot," the temporary huts in which new immigrants are housed before being given permanent places.

They have walked many miles through various sections of the "incredible" city of Jerusalem, seemingly without a rival, in an attempt to understand and compare the different cultures which have sprung from the same religion. The Meyers prayed, for example, in a Yemenite synagogue where the congregation without shoes sits on cushions on the floor. How complex the religious culture is and how varied is indicated by the estimate that there are 450 synagogues in Jerusalem, no two of them alike. Furthermore, the Meyers tried to become acquainted with as many persons as possible from all walks of life in their attempt to understand the structure of life in this dynamic and complex little country. And finally they made an effort to attend theaters, music recitals, and art exhibitions, though Mr. Meyer's long and exhausting hours of study curtailed many such artistic activities. He saw nevertheless the Habimah Theater group in their productions of King Lear and Medea.

UNDER the dedicated leadership of Professor George E. Diller, the Committee on Graduate Fellowships (Copenhaver, English, Finch, Hurd, J. B. Lyons, and Skilling) after many lengthy meetings have had the rewarding experiences of reading reports and letters from past Reynolds Scholars, energetic documents filled with their dreams and activities in different countries. All these men end trying to show their gratitude to the college which made their year abroad possible.

Marshall T. Meyer suggests the frame of mind of all when he attempts to find the right phrases. "I must unqualifiedly state that I shall be eternally grateful to Dartmouth for making this great adventure possible. No amount of writing can do justice to all that I am learning. I am working more or less at capacity, though I feel that lam still not learning enough. ... I really cannot tell you how much this experience means to me, first because I cannot describe it, second because I myself at this time cannot fully appreciate the extent of influence this year will have on my life and thought. I shall gain much more than I thought possible before I realized how big the world is and how narrow one can become by only remaining among those people and ideas he knows and with which he feels at home."

James B. Reynolds '90, whose bequest made possible the 'scholarships bearing his name.

Joseph D. Mathewson '55 (right), former editor of "The Dartmouth," now a Reynolds Scholarin Italy, shown with Hans Schoenberg, a native German who has U.S. citizenship.

Nathan K. Kotz '55 of Washington, D. C., isstudying political science at the Universityof London. He also has traveled extensivelyin Spain during his year abroad.

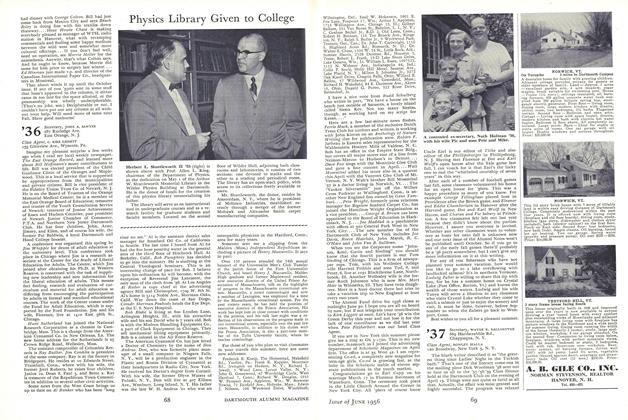

Frederick A. Stahl '52 (right), student at the Polytechnic School of Architecture in London, is shown at the Building Research Station with William Allen (center), head of the architects division, and Roland Wedgwood, examining some modular work.

Martin B. Friedman '55 of Hewlett, N. V.,has been enabled by his Reynolds Scholarship to realize a long-standing ambition tohave a year of study in Paris.

Marshall T. Meyer '52 of Norwich, Conn., and his wife Naomi are shown in the new city of Jerusalem, where arduous study is combined with hard living conditions. In the background can be seek Mt. Zion at the left, a Jordanian military establishment in the center, and, behind Meyer's shoulder, the Valley of Hinnom, where Moloch worshippers offered human sacrifice and where the Biblical conception of Hell began.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLEARN AMERICAN

June 1956 By EDWARD C. KIRKLAND '16 -

Feature

FeatureA NEW CONCEPT of Dormitory Living

June 1956 -

Feature

FeatureTHE NICHOLS ERA

June 1956 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1956 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1956 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

June 1956 By JOHN A. SAWYER, C. KIRK LIGGETT

Features

-

Feature

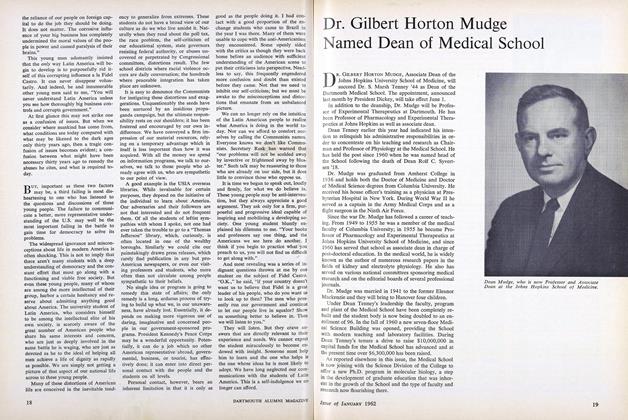

FeatureDr. Gilbert Horton Mudge Named Dean of Medical School

January 1962 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFashion Corner: Two Outing Club Looks

NOVEMBER 1989 -

Cover Story

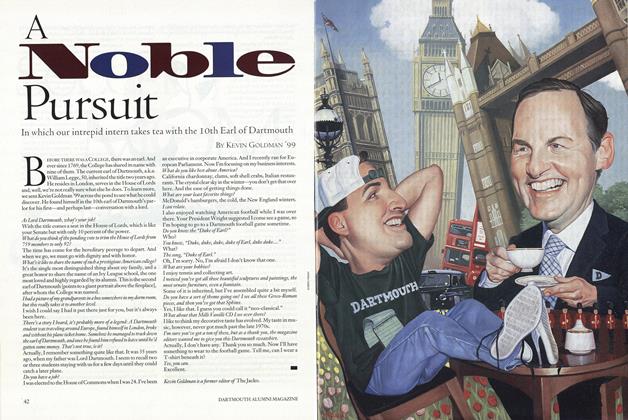

Cover StoryTHE DARTMOUTH REVIEW

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

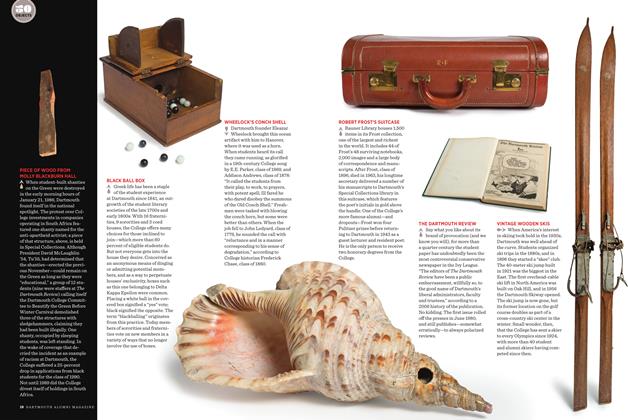

FeatureWorkouts From Hell

Jan/Feb 2002 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Feature

FeatureThird Panel Discussion

October 1951 By JAMES S. DUNCAN -

Feature

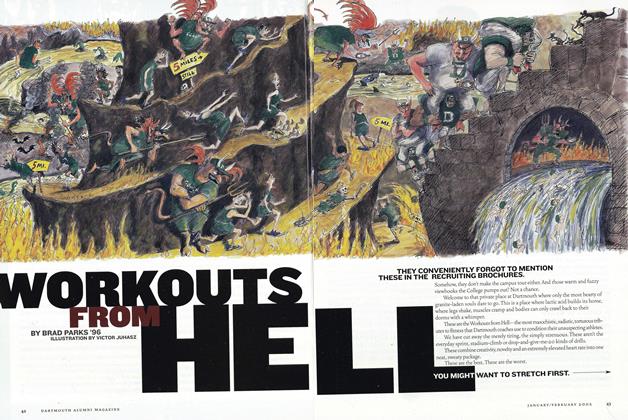

FeatureA Noble Pursuit

DECEMBER 1999 By Kevin Goldman ’99