National service • institutional affiliations • an apology • a personal note

In my five-year report I said: "I have engaged in fewer 'outside' activities than most other college presidents. For many, a college presidency has been a national platform used either to build up a career or to participate in nationwide decision-making. I find that my Dartmouth respon- sibilities consume all of my time . I had fully expected and hoped that 1 would complete the presidency of Dartmouth College under that philosophy. However, fate interfered.

In April of 1979, my wife Jean and I listened to one of Presi- dent Carter's national speeches, one dealing with energy. When he announced that he planned to appoint a presidential commis- sion to look into the accident at Three Mile Island, I thought that that wa§ a good idea and promptly put it out of my mind. Some ten days later I received a late evening phone call from the White House informing me that I was one of the finalists among candidates for chairmanship of the commission. I was nearly speechless, but I agreed to think overnight about whether I would accept the appointment if it were offered to me. I also expressed the hope that somebody else would be chosen. Less than 48 hours later, Jean and I were standing in the Oval Office to meet Presi- dent Carter and, before the two of us faced the Washington press corps, to receive his personal briefing on what he expected of the commission. That was the beginning of the most hectic seven months of my entire life.

I had not accepted the position lightly. After an all-night dis- cussion with my wife, I called the chairman of the Board of Trustees to present him with the pros and cons of accepting such a position. As I remember, the cons were much weightier than the pros. I particularly warned him that the commission was likely to write an extremely controversial report which could result in a lot of people being very angry at me and some might take their anger out on Dartmouth College. The chairman, David McLaughlin '54, listened to me most patiently and then said: "I believe your arguments are correct. However, I predict that if you should be chosen, when the call comes from the White House telling you that you were the one person in the country selected to undertake this all-important task, you will forget all your arguments and say 'Yes, Mr. President!' " As usual, David McLaughlin proved to be absolutely right.

I was asked by the White House whether I had taken any public position on nuclear power. Careful research into my speeches proved that my first answer was correct, namely that I had spoken on the subject only once which happened to have been less than a year earlier. It was at a convocation speech whose theme was: "Do not accept over-simplified solutions to highly complex problems." As one of several illustrations, I used the debate on nuclear power, and during the talk I made the fol- lowing remarks: "You are either pro or you are con, and you better be all the way pro or all the way con, or you're going to get it from both sides. And that way there is little room left for con- structive debate. ... I feel a tremendous urgency to see construc- tive and intelligent planning efforts started. The outcome of such planning will require significant changes-in life-style for all of us. And that is a hard thing to bring about because people first have to understand how difficult the problems are. In such a situation a demagogue has a tremendous advantage because he will sell you a simplistic solution that may be wrong but is easy to understand." When I gave that speech, nothing was further from my mind than the thought that I could end up playing a major role in such a debate.

The morning after that historic visit to the White House, I woke up in a Washington hotel realizing that I had in my hands a powerful executive order, more than a million dollars in funds im- mediately available with promise of more (we would eventually spend $3 million), with a mandate to carry out an investigation into the single most controversial subject in the nation, and with absolutely nobody working for me. The President had appointed the members of the commission but left the appointment of the staff to the chairman. We were ordered to present a report within six months of our first meeting. I called all my fellow com- missioners on the phone and arranged the first meeting for two weeks later. That left me only two weeks to straighten out my af- fairs at Dartmouth and to recruit the senior officers who would head up the staff. To the outside world we presented an image of deep and impartial thought about one of the perplexing problems of our age. That image was true.

Equally true was a six-month battle to attract truly outstanding individuals to work for the commission, at considerable personal sacrifice, and to hold onto them in spite of increasingly impossible working conditions. As our investigation turned up more and more areas that we had to look irlto, the size of our staff grew from an original estimated 25 people to over 60 and that di not include consultants. We worked in office space that had been rented for the estimated staff of 25! The six-month period is a blur of deep discussions, fascinating revelations at public hearings, worrying about how one gets a duplicating machine that will turn out more than one copy a minute, outstanding detects work by our staff, working 16-hour days six (and later seven) da>s a week, a superb collection of commissioners of great diversity' and never having enough secretarial and clerical help.

Six months later we reported to the President of the Unite States and to the nation. I still find it difficult to believe that our report has received such wide approval. Individuals who could never agree on anything concerning nuclear power would offer equal praise for the report. Perhaps of all the compliments our com- mission received, the one that meant the most to me was the repeated praise for having written possibly the most readable report ever turned out by a presidential commission.

When I accepted the chairmanship, I insisted that I had to devote at least half of my time to Dartmouth College. I kept that timetable for the first five months, but with six weeks to go I realized that unless I went to Washington full-time the commis- sion would be unable to complete its report. Even the half-and- half distribution came at the most busy period for the president of the College. For several weeks I alternated a week in Washington with a week out on alumni tour. I got back on campus in time for that incredibly hectic period trustee meeting, commencement, and reunions. Normally, I would have been scheduled to teach a course in the summer, but since Jean and I had gone nine years without taking a lengthy vacation, I had planned to take some time off last summer. We did manage a one-week vacation!

Finally, the report was made public. We presented it first to the President. Then we briefed congressional leaders and held a ma- jor news conference; many of us held individual news conferences and appeared on talk shows; we participated in a more detailed briefing of the press on individual subjects and testified before an unprecedented joint hearing held by major committees of the Senate and the House. All this happened within 48 hours. Retur- ning the next day to Hanover, I was more tired than I had been in my entire life. There was a major gathering of alumni in town, and I was scheduled to give a speech. The decision had been made in my absence to open that speech up to the entire Dartmouth community; I would find Spaulding Auditorium jammed with people and with closed circuit TV to Alumni Hall, and would later learn that many who were unable to get in listened over the radio. An hour before I had to appear I told Jean that I had used up all my reserves in the final push on the report and that I simply could not go through with the speech. Somehow I made it to the stage of Spaulding Auditorium where, after David McLaughlin's introduction, I was unexpectedly greeted with a prolonged stand- ing ovation by the audience before I had said anything. 1 learned an important lesson, that given the right stimulation human beings have some extra reserves of which they are not even aware. 1 am told that I gave a good speech. (It was reprinted in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.) I remember little of it, but I will never forget the warmth and affection of that audience.

I was widely quoted as saying that if I had known what those seven months would be like, I would never have accepted the assignment. I also said that I had a great sense of achievement and I was glad that I had accepted the assignment. Both statements are true.

Why did I accept? I had absolutely nothing to gain by serving as chairman of a presidential commission. I have no desire to enter the political scene, least of all on a national scale. My long- range ambition is to complete my term as president of the College and then return to full-time teaching at Dartmouth. I had not formed strong convictions one way or the other about nuclear power. 1 was not even knowledgeable on the subject, but I did know enough to be able to learn and to learn fast. I also had had a great deal of experience in trying to bring about consensus in a highly diverse group. Perhaps chairing faculty meetings was the most important experience to prepare me for the chairmanship. In the last analysis, I believe I accepted precisely because I did not have a vested interest one way or the other in the question of nuclear power and because I had nothing to gain. I felt the Presi- dent of the United States deserved as head of the commission someone whose sole commitment would be to the truth.

/once asked John Dickey what happened at Ivy Presi- dents' meetings. He said: "We fight about football." Naturally, I assumed that he was joking. I have since learned that his statement was not quite accurate; we also fight about hockey and basketball.

Higher education is going through very difficult times, fighting, if not for survival, at least for the maintenance of quality. Under such circumstances one would like to believe that there are well- organized and well-staffed national organizations that will repre- sent the interests of higher education. Dartmouth belongs to several national and some regional organizations. Unfortunately, I have found most of them to be of limited usefulness.

The association that tries to represent all colleges and univer- sities in the United States has an incredibly diverse membership. The roughly 3,000 institutions of higher education have little or nothing in common. Harvard University, a small community college, and a vocational school all serve useful functions for society. They are, however, totally different in their character, their priorities, and their needs. Stands taken by such associations end up being enormously watered down so as to capture the wishes of a majority of their members. These associations also tend to be so huge that their meetings do not lend themselves to thoughtful, in-depth discussions, and they have very limited im- pact as they lobby for higher education.

Even regional organizations have difficulty reaching agreement on controversial issues. They tend to be most useful when, like the New England Library Information Network, they address a single common problem. Informal meetings of college presidents can be useful for exchanging ideas on common problems and sharing experiences. Similarly, a number of informal meetings have sprung up among other levels of administrative officers. Provosts and academic vice presidents from some ten institutions meet frequently. The directors of admissions, athletics, and finan- cial aid meet periodically with their counterparts in Ivy in- stitutions and M.I.T. These groupings are small enough so that useful discussion can occur, and there are sufficient similarities in the problems being faced to make the meetings productive.

I wish that I could add that the meetings of the Ivy presidents that occur twice a year (and include the president of M.I.T. on non-athletic matters) constitute an extremely important and productive forum. Unfortunately, that has not been my ex- perience. In 1980, the similarities among our institutions are more a matter of tradition than fact. Among the nine institutions including M.1.T., seven are pre-Revolutionary and two are much younger. Six are today predominantly graduate- and professional-school-oriented; at the other three, undergraduates still far outnumber graduate students. Some of the institutions de- pend very heavily for their programs on major federal support; others, like Dartmouth, receive federal support only in certain selective areas. Six have urban locations and three are rural. They are not even all private institutions, as Cornell has some state- supported schools. In competition for the best undergraduates in the country, in which we all participate, some of us have significantly more success than others.

There have been various attempts during the last decade, at the initiative of one or more of the Ivy presidents, to bring about cooperative academic efforts or joint planning on major projects. None of these has been truly successful because of the diversity of our institutions. Arrangements among two to four institutions have succeeded, but the group as a whole is too heterogeneous and too far-spread for an "Ivy effort."

John Dickey's remark about Ivy presidents had considerable depth to it. In a very real sense we are tied together by the fact that when the Ivy schools were organized into an athletic league through a joint agreement in 1954, the presidents were designated as the policy committee. The one responsibility we must exercise as a group is establishing standards for our athletic programs and defending the Ivy philosophy that every athlete is a student first and an athlete second. This has indeed been a challenging task in the 1970s as we have seen an enormous increase in the professionalization of athletics at colleges and universities nationally. Last year, on the 25th anniversary of the original Ivy agreement, the presidents issued an updated and strengthened version of the original Ivy principles, reaffirming our faith in the Ivy philosophy.

Implementation of this philosophy has been far from easy and has required continued vigilance. A number of times we have had to take corrective measures or clamp down on abuses at in- dividual institutions. In spite of many strains we have succeeded in maintaining similar procedures and common dates for our ad- missions, and we monitor each others' financial-aid awards to assure that they are given on the basis of need and not athletic ability. Perhaps our most difficult task has been insuring that stu- dent athletes be representative of the student body as a whole, without significant presence of students who do not meet the nor- mal admissions standards of an institution but are recruited purely to improve the quality of athletic teams.

I firmly believe in the contribution competitive athletics can make toward the building of character, but I have watched with deep regret the development of some very dangerous national trends. Competitive athletics, particularly in certain sports, has become big business at many universities. The filling of enormous stadiums and the availability of large amounts of television revenue have given athletic programs a financial importance and an independence over which the faculties and sometimes even the presidents of the institutions have lost control. Some of the worst cases of abuses have been well documented in the public press. Naturally, any athletic team wants to win. But the philosophy that "winning is everything" is a destructive one to which I hope the Ivy institutions will never succumb.

Most alumni will remember a time when coaching was carried out by individuals who would make a long-term commitment to the institution and participate in the coaching of several different teams. They were usually assisted by part-time seasonal coaches so that the athletes could receive quality, individualized instruc- tion. As part of a national trend, the Ivies have gone toward full- time professional coaching staffs. Besides the financial im- plications, this has created a situation where each school has many coaches who cannot aspire to become a head coach at that particular institution and therefore look at their positions primarily as a steppingstone toward becoming head coach somewhere else. Many such individuals feel that having a spec- tacular winning record is the only way they will be measured in competing for higher positions, and this can have a negative effect on the Ivy philosophy. The league presidents have attempted to reverse this trend, but it has been a slow and painful process.

The most useful association to which we belong is the Consor- tium on Financing Higher Education (COFHE). The consortium grew out of a relatively modest idea I had early in my term as president. With the help of the Sloan Foundation, I put together nine distinguished private institutions in the northeast as a plan- ning group on the financing of undergraduate education, with particular emphasis on the increasing complexity of financial aid for students. From that modest beginning COFHE grew into a national association of 30 of the best-known private institutions of higher education from all over the nation.

While the membership varies enormously in size and complex- ity of the institution, we have in common high-quality un- dergraduate liberal-arts programs. As undergraduate schools we are each other's chief competitors, but the consortium serves three purposes: It gathers and shares data on our undergraduate enrollments and programs, it conducts in-depth studies of interest to the member institutions, and it represents our views in Washington in connection with student-related legislation. The secret of the success of the organization has been the simplicity of its structure and the limitation of its mandate to a few important and achievable projects. We have intentionally held the membership to 30 so as to make a meeting of all their presidents or representatives realistically possible.

For the first time we have been able to obtain reliable and com- parable data from these institutions. It is enormously helpful and instructive to compare Dartmouth's achievements or problems with those of our sister institutions. Equally important have been comparative cost studies in areas as varied as student affairs and alumni relations. A small but highly competent consortium staff has been able to produce these results because each of the in- stitutions has pledged to provide the data and to work with the staff in bringing them into a common format. Dartmouth's share of the total expenses is about half of the compensation of a junior administrative officer. We would require a significant staff to produce comparable results but we could never obtain them on our own because the data would not be available.

The consortium is governed by a policy committee consisting of one representative from each institution, a group that meets several times a year to chart the course of work. It also has a board of directors consisting of six presidents and the chairman of the policy committee. This year I am completing my final year as a member of this board as well as my second year as chairman. Special tribute should go to President Colin Campbell of Wesleyan University, under whose chairmanship the consortium grew into its present expanded and much more important stature. He is continuing to shepherd one of our most important projects: He was successful in obtaining a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to study the likely impact of federal legisla- tion that is forcing us to change the mandatory retirement age to 70. This study, which is almost complete, will both analyze the likely impact and suggest measures to alleviate the highly negative results of this legislation on our institutions. It is, for ex- ample, exploring new options for early retirement that may be attractive to faculty and administrative officers.

But in the last analysis the credit for the consortium's success must go to its two extremely able executive directors. Richard Ramsden, a Brown alumnus, was the first full-time executive director. To my very pleasant surprise he decided to locate the consortium offices at Dartmouth. When he left COFHE to become the chief financial officer of Brown University, we were able to recruit Kay Hanson, the current executive director. For personal reasons she moved the office to M.1.T., where she has continued the high standards of excellence to which we have become accustomed. We are currently represented in Washington by Theodore Bracken '65, who is our one-person Washington of- fice. In a sense, a mere 30 institutions do not have the political clout to "force" the passage of legislation, and the fact that we are all private institutions would appear to be a handicap in thai most institutions of higher education are state-supported. Never- theless, COFHE has several times had important positive impact on legislation concerning student financial aid. We have achiev this not by trying to use muscle but by producing position paper3 that several legislators have described as the most thoughtful the) have read. We have been extremely careful to come up W1 positions that are fair to the entire system of higher education an are not special pleading for our unique institutions. This has been the one inter-institutional association in which both our financia investment and our investment of time and effort have been repaid many times.

T m here is so much more that I would like to say about K Dartmouth College. But one must arrive at a rea- sonable compromise between comprehensiveness and readability. To assure that the length of this report does not frighten all readers away, I have to make a number of omissions. There are many topics discussed in my five-year report that would have been well worth updating or re-emphasizing, but I have had to decide to stand on my previous statements.

In particular, I want to apologize to the large number of un- mentioned individuals who have nevertheless made significant contributions to today's Dartmouth.

There are a few individuals, however, whose contributions must be acknowledged. Leonard Rieser has served Dartmouth College as a senior administrative officer longer than almost any of his counterparts at other institutions. During the past decade he has served as provost and dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, most of that time carrying both responsibilities. In addition, as the senior academic officer he has had to act for the president in his absence. Leonard Rieser's impact will be felt most strongly in terms of the quality of today's faculty. But he has also served as chairman of the Facilities Planning Board and has been one of the most important advisers of the president and the Board of Trustees. Having also undertaken a major role in the Campaign for Dartmouth, he had reached a level of responsibilities that no one person can carry. A search for a new dean of the faculty was instituted, therefore, and Hans Penner, professor of religion, has been appointed to that position. Leonard Rieser is one of the most respected academic officers in the nation, and we have been fortunate to have his services available for two decades.

Next, I want to express my appreciation to the small and ex- tremely hard-working staff of my own office. They have cheer- fully taken on ever-increasing responsibilities as the complexity of the institution grew. I am particularly indebted to Alexander Fanelli '42 and Ruth Laßombard, who have been with me for the entire period of my presidency and have done everything humanly possible to ease the burden. My first appointment as president- elect was Lucretia Martin, who served me ably and loyally as special assistant. Her assignment as director of major gifts for the Campaign for Dartmouth has contributed significantly to the success of that effort, but the campaign's gain has been the president's loss.

Finally, there is Jean. When I say that I could not have done this job without the help and the support of my wife, I am making a simple factual statement. She has been possibly the most active president's wife in the entire nation. Her contributions to the welfare of the College and of its president have been manifold; often they have been achieved at great personal sacrifice. The 13th presidency has been a two-person team effort. I hope that future historians will record accurately just how important the other half of the presidential team was to the success of my ad- ministration. I would like to express publicly my deepest thanks to Jean Alexander Kemeny.

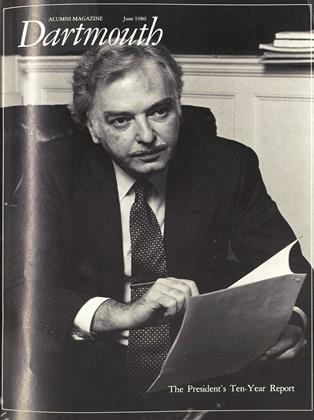

s most of you know, I submitted my resignation as president of Dartmouth College, effective August 1,1981. When Lloyd Brace '25, then chairman of the Board of Trustees, offered me the position, he made two points emphatically. First of all, that I could be fired by the trustees at any time. Secondly, that if I was not fired, the board expected me to serve for no less than ten years. I responded to that by accepting both conditions, but stating that under no cir- cumstances would I serve for more than 15 years.

It is easy to think of the Wheelock Succession as consisting of presidents with exceptionally long terms. It is easy, but not really accurate. Of the first 12 presidents, four served for terms of 25 to 35 years. Of these, two were great leaders and two were not. The other eight averaged less than ten years' service.

By mid-summer next year I will have served 11 and a half years as president of the College; since I took office on March 1, I will have gone through the most demanding period of the year an even dozen times. The March-June period includes the annual budget cycle, alumni tour, two of the four trustee meetings, numerous faculty meetings, commencement, and reunions. Sometimes it also includes a spring uprising! It is a sad comment on the problems of the seventies that many of my contemporaries stepped down in less than ten years, and I am one of very few who has gone past the ten-year mark.

More than a year ago I took stock of the achievements of my administration and of the problems confronting us in the future. I made a realistic evaluation as to how far I could go in solving these problems. I am very proud of the achievements of the past decade, and I am optimistic that we have set into motion programs whose full impact will be felt in the future. I also faced up to the fact that some of my dreams would be realized only at a later date and that I would have to watch these achievements from the sidelines. I thus determined that the best time for me to step down was in the period 1980-82.

The deciding factor was the Campaign for Dartmouth. Having made a complete commitment to this campaign, I asked myself how I could make the greatest contribution to its success. I felt that stepping down after three years of a five-year campaign was wrong, but I also concluded that to stay on until the last day of the campaign was less than ideal. I recalled the great success of the Third Century Fund. In a three-and-a-half-year campaign a new president came on board nine months before its conclusion. I feel that this had a positive impact in carrying us over the top. I hope that no one will misinterpret this in any sense as a criticism of the 12th president; I have on countless occasions expressed my great admiration for John Dickey. Still, the coming of a new president is like the coming of spring: It creates an atmosphere of optimism and a sense of renewal that is important for the institu- tion. I hope, by the end of the fourth year of the campaign; to help bring it to a point that the goal appears clearly reachable. I hope then that the 14th president will push it far over the top.

I would like to express to the Board of Trustees my deepest gratitude for having given me the opportunity to serve Dartmouth College as its 13th president. Despite the frustrations of the seventies, it has been a deeply satisfying experience. Whatever may happen to me in the future, this service will always be the most meaningful experience of my life. Frankly, I would not have missed it for anything!

I shall conclude this report with words that I spoke at the celebration of the tenth anniversary of my inauguration. I men- tioned that as the anniversary approached, several reporters asked me "When are you going to leave Dartmouth?" The answer to that is that I do not plan to leave Dartmouth. After the in- auguration of the next president I will have a year's sabbatical and then return to full-time teaching. We have a small house in Hanover in which we hope to live for the rest of our lives. While the form of my service to the institution has changed from time to time and will change again, my service will continue. My commit- ment to Dartmouth College is the same as my commitment to my wife: "till death do us part."

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSIENNA CRAIG

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

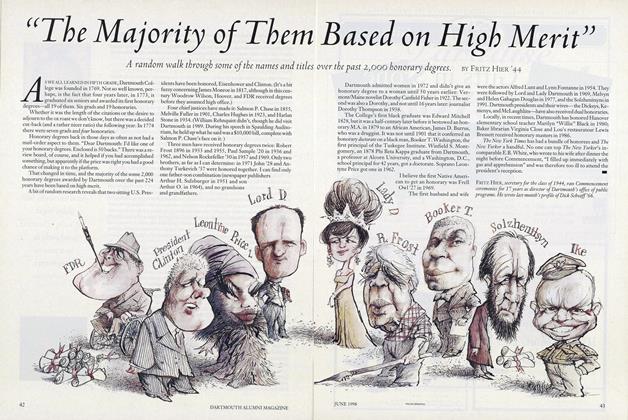

Feature"The Majority of Them Based on High Merit"

JUNE 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Nov/Dec 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureFuturescapes

May 1974 By R.B.G. -

Feature

FeatureFish Dinner 1983

OCTOBER, 1908 By Richard Eberhart '26 -

Feature

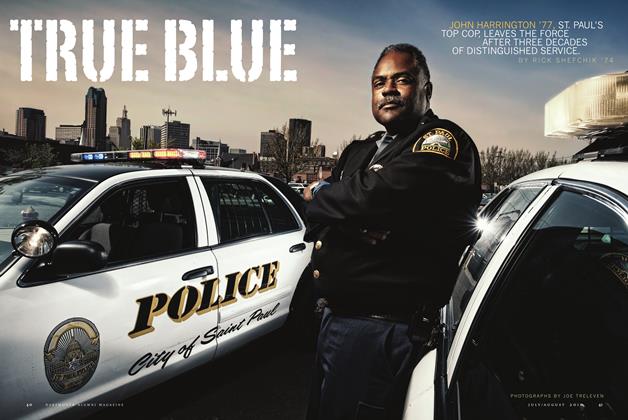

FeatureTrue Blue

July/Aug 2010 By RICK SHEFCHIK ’74