The Undergraduate Chair this year willbe written by a series of guest editors.Lincoln A. Mitchell '58, editor of The Dartmouth, has contributed this month'sarticle, the first in the series.

DARTMOUTH opened her 189year with the Convocation exercises that have come to be traditional over the years. President Dickey spoke for the College, Undergraduate Council president Joseph Blake '58 for the student body, and the simple exercises concluded in the singing of "Men of Dartmouth."

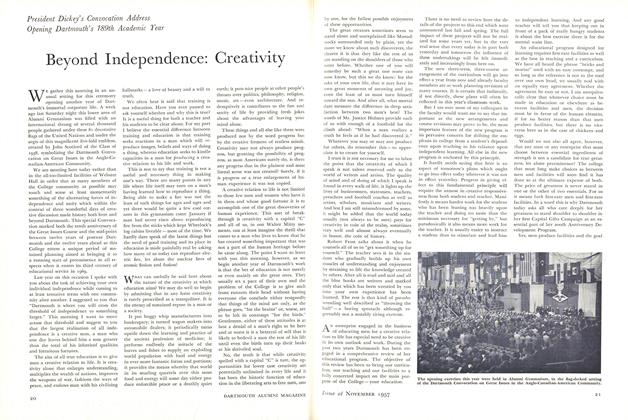

This Convocation was essentially the same as many convocations in the long history of the College, and yet, as the President spoke, the undergraduate could not but realize the very real paradox which this institution now faces. For this "opening," this revitalization of Dartmouth, was not held within the solemn, aged atmosphere of Webster Hall; die traditional setting of this building, its many paintings of Daniel Webster a testimonial to our institutional forebears, was replaced with an Alumni Gymnasium gone international. There, under the decorative flags of the 81 "United Nations" where ten days before an international throng had gathered for the Anglo-Canadian-American Convocation, Dartmouth began a new year.

At such a Convocation, one's thoughts naturally turn to tradition. The undergraduate usually thinks of the history, the customs, and the ideals of which he has become an integral part; he tries to realign himself with his "institutional heritage" and apply this to his personal present. This is a particularly pertinent and customary reaction at an institution which is so fully ingrained with tradition as is Dartmouth.

And yet, as the College opened, our thoughts were not directed backward and inward, to our past and our traditions; rather, forward and outward, to our future and our society. The President spoke not of tradition and heritage, but of planning and progressivism. Here, epitomized in a single hour, is the paradox which Dartmouth faces today: the dilemma posed by the conflict between the traditional and the progressive.

This is a very real problem. Almost every aspect of campus life is presently feeling this conflict and is intensely conscious of the fight between the traditional values and ideas, which we are all wont to continue, and the new concepts and plans which must be endorsed for a continued vitality.

The controversy over the architecture of the Hopkins Center and the new dormitories exemplifies perfectly this condition. When the plans for these buildings were announced, a wave of protest, both undergraduate and alumni, arose to damn the inclusion of modern architecture on the Dartmouth campus. "It doesn't belong there," these protagonists claimed, "and it is entirely out of context with the other College buildings; why, it violates all the tradition that is Dartmouth."

This is a basic conflict between the traditional and the progressive. We have a choice; we can erect buildings which embody the modified Georgian architecture of Baker Library and the Tuck and Thayer Schools, or buildings which reflect the architectural thinking of the day, the so-called "modern" ideal. This choice appears to me to be a simple one, and one which can epitomize the real feeling at Dartmouth. If we build in Georgian, we are looking backward to our traditional past, demonstrating to the world that Dartmouth swims deep in the waters of tradition, so deep that she is in real danger of drowning as our culture moves forward. And if we turn to the modem, we inherently announce that this College, while cherishing its tradition, believes foremost in a vital future, not an illustrious past. This College does believe in this kind of a future, and it is this future that we must perpetuate.

If we do perpetuate, if we construct with the idea of representing the present, not cherishing the past, then we have continued the Dartmouth heritage, a heritage which is not only for us to accept and enjoy but also to nurture and enlarge. And if we refuse to build a representative building today, a building characteristic of modern architectural design, then we are denying a part of this heritage to future generations. It is our portion of this institutional heritage that we would be refusing to contribute.

There is a second great conflict between the traditional and the modern in this College; that is the role of the undergraduate. He is torn by many things, confused by the different parts that he is expected to play, and mystified by the seeming conflict between what he feels he should be and what he feels he is expected to be.

This is most obvious in the freshman year. A man arrives at Dartmouth and naturally assumes that he is expected to act as-and be - a gentleman. Yet, he is also confronted with the role that has become traditional for the Dartmouth undergraduate: the hell-raising, harddrinking, anti-academic, T-shirted, virile individualist of the North Country. Whether this characterization has much of a basis in fact I do not know; stories grow with age. But this is the average individual's personification of a Dartmouth student.

And so sits the freshman, torn between two desires: one, to act as he feels a gentleman should; the other, to represent to the world the traditional "Dartmouth Indian." He may want to pursue his studies seriously, yet social pressure inclines him toward neglecting them and taking his "gentleman's C." He may feel that shaving is a morning ritual which should be observed, yet succumb to the cry for a "two-day growth." And he may remain civilized in Boston, Northampton, and Saratoga Springs, but only if he rejects the tradition-established role of "hell-raiser." The freshman is, in short, faced with a complicated paradox when he enters Dartmouth, a paradox posed by the conflict between what has come to be accepted as a traditional role and the modern role that he would like to pursue.

If this is tradition, it is unworthy of this College. A man may be a gentleman, yet not a pansy; a serious student, yet not an emaciated egghead; polite, yet not puny.

This is not to say that the undergraduate of today is a form of lower animal life; fortunately, he survives much of what the traditional role would make of him. It is to say that this tradition, or the aborted form that exists today, is an unhealthy and confusing influence on the incoming student. Much as it is important that this College make men, it is fully as important that she make gentlemen.

A third great conflict between tradition and modernism exists on this campus with the problem of automobiles. The situation posed by a mechanized age was brought to a hysterical peak last year when five undergraduates were killed in automobile collisions.

Everyone started clamoring that something had to be done to alleviate this situation. Everyone connected with the College wras concerned.

Since that time, The Dartmouth and the Undergraduate Council have established a program of bus serv ice and information which is designed to combat the problem in a practical way.

But underlying the emotional response of last spring is a more basic condition: the Administration, faculty, and many alumni feel that automobiles have little or no place on the Hanover Plain. They dislike the supposed frequency with which students leave Hanover, going to Northampton or Saratoga Springs instead of the woods or the library. "We didn't have cars when we were in college," they reason, "so why should you?"

All right, why should we? Dartmouth undergraduates of the nineties, the twenties and the thirties stayed in Hanover; without readily accessible transportation, they had no choice. The student of today, if he is able to save enough money to buy a car, does have a choice. He is representative of his society; as such, he is a highly mobile individual, capable of covering long distances in a short period of time. We cannot question this condition here; it is a fact with which we must live.

Here lies the paradox: tradition would have the undergraduate stay in Hanover or the nearby woods, but our modern society has made it possible, and reasonable, for him to venture forth in search of female companionship.

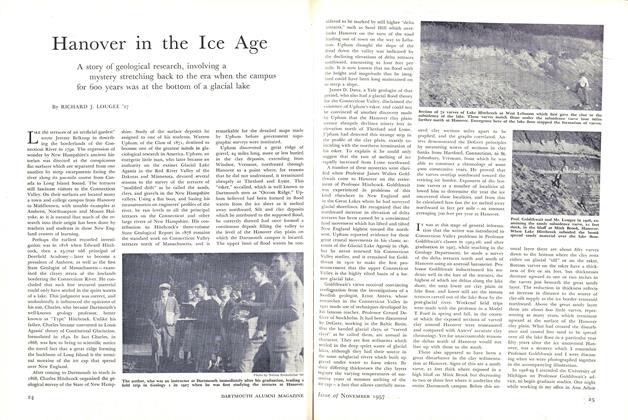

Lincoln A. Mitchell '58 of Minneapolis, who is editor of "The Dartmouth" this year. He prepared for Dartmouth at Hebron Academy and is a memer of Kappa Sigma fraternity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHanover in the Ice Age

November 1957 By RICHARD J. LOUGEE '27 -

Feature

FeatureBeyond Independence: Creativity

November 1957 -

Feature

FeatureGlass Funds and the Capital Campaign

November 1957 -

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Form Association

November 1957 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

November 1957 By WILLIAM L. CLEAVES, F. STIRLING WILSON, RODERIQUE F. SOULE1 more ...