The broad strategy behind it is to give the student more responsibility and time for educating himself

FAR-REACHING changes in the academic program of the College have been recommended to the Board of Trustees by the Dartmouth faculty. The proposed program, approved at a general faculty meeting on March 5, is one of the most important developments to date in the complete review of Dartmouth life being carried forward under the Trustees Planning Committee. It is the culmination of more than two years of study and discussion directed by a joint committee of faculty and Trustees.

The major change recommended is the introduction of a three-term, three-course program, beginning with the academic year 1958-59. Each term will be about eleven weeks long, with Christmas vacation coming at the end of the first term and spring vacation at the end of the second term. The normal program for most students each term will be three courses (meeting four times a week) instead of the five courses each semester as is now the case. The number of class hours for each course will not be much less than under the semester plan, and the student will have substantially greater and more concentrated time for each course and will be able to give sustained attention to independent work.

The requirement for the degree will be reduced from 40 to 37 courses, except for ROTC students, who will need 39 courses, including eight ROTC courses. Although the three-term, three-course plan reduces the number of electives open to the student, qualified men will be permitted to take two additional courses without charge.

The new academic program also calls for a plan of general reading for all students; continues the requirement that courses be distributed among the sciences, social sciences and humanities, with some increased emphasis on humanistic studies; modifies the present English 1-2 requirement and gives central importance to the effective use of English throughout the entire curriculum; and continues the Great Issues course for all seniors. It also sets three terms of college-level study as a foreign language proficiency requirement, with the expectation that most students would achieve it by the end of the second term of freshman year; approves in principle the continued exploration of divisional courses, such as the "double" Humanities courses tentatively adopted by that Division; and continues the existing ROTC programs as an integral part of the revised curriculum.

Under the program of general reading for all students, the first two years will be supervised by a faculty committee and will be aimed at widening the student's interests. During the last two years the student's general reading will be directed by the major department and will serve to deepen understanding of his chosen area of concentration.

Training in the effective use of English is central in the curriculum. Men who show proficiency in English may be given whole or partial exemption from the normal requirement of one year of English study, but throughout the whole college program there will be increased stress in all courses on correct and effective expression.

In addition to the curriculum changes recommended for present action, the faculty approved several "guideposts for subsequent change." These include a reexamination of all courses and major programs, within the framework of the new curriculum; reading courses for credit; the extension of independent projects in the senior year; greater provision for the particularly able student by the extension of "honors," independent study and advanced placement; and continued exploration of the possibility of raising the overall student teacher ratio without sacrificing educational effectiveness.

FOLLOWING, with some slight omission of sections that either summarize points or deal with curriculum mechanics primarily of faculty interest, is the full text of the revised report, An EducationalProgram for Dartmouth, "which was the basis for the faculty action of March 5:

INTRODUCTION

The Committee on Educational Policy and the Subcommittee on Educational Program Planning submit to the Faculty a further report directed toward a revision of the curriculum. Since the Faculty received "An Educational Program for Dartmouth" in March 1956, the joint committees have had the benefit of participating in the six faculty meetings and of learning the views of the three divisions of the Faculty on various aspects of the "Program" and of receiving a number of constructive written criticisms and suggestions from individual members of the Faculty

In making these revised proposals the joint committees have no wish to weary the Faculty by an elaboration of their educational ideals. These are far from original; criticism, such as there was, was generally aimed at their triteness and selfevidence rather than at their validity. It is, however, perhaps worth reaffirming that the primary objective is a determined effort to increase the student's responsibility for his own education and to shift the emphasis from teaching to learning. The joint committees realize that this objective can be realized within the framework of almost any curriculum and furthermore that no curriculum can guarantee it. It is unfortunately safer to predict that certain procedures will diminish self-education than that others will enhance it. The proposals outlined below are based on a belief, arguable, but not demonstrable with Euclidean certainty, that self-education will be helped though not guaran- teed. They are intended to set a direction of change, and experience gained in their operation must be the guide to further evolution.

In conformity with this evolutionary point of view the joint committees now make (a) proposals for immediate change, and (b) suggestions intended as guides for further evolution. The former, if acceptable to the Faculty, would be put into effect as soon as college machinery and the requirements of orderly transition permit. The latter consists essentially of suggestions to be explored actively at the divisional, the departmental, and the individual level in the course of the next two or three years. Many of them, and indeed perhaps all, are constitutionally compatible with the present curricular framework so that not merely exploration but also active trial of them is already possible for the department or the individual teacher. It is also recognized that the relevance and value of the various suggestions lor future evolution will vary from department to department and from course to course. The joint committees, nevertheless, wish to include them in their report because it is their conviction that a vigorous and critical exploration of these guideposts for subsequent change by individual departments and individual instructors might ultimately contribute considerably to the quality of a Dartmouth education. It is their belief that the energy and imagination with which they are explored would be greatly benefited by an expression of general faculty approval of such exploration.

Persuading a student to learn for himself is almost certainly harder and may be in some cases more time-consuming than teaching him. This introduces a highly speculative element into any comparison of faculty workloads under different curricular schemes. The elimination of large required lecture courses from the revised proposals further weakens the relevance of any argument that faculty compensation might be beneficially affected by proposed changes. The case for the revised proposals is accordingly based solely on their potential contribution to the realization of our primary educational objective indicated above.

PROPOSALS FOR IMMEDIATE ACTION

These may be briefly summarized as:

(a) The adoption of a three-term, three-course calendar.

(b) The institution of an independent program of general reading for the first two years and of independent reading prescribed by the major department in the last two years.

(c) The continued exploration of divisional courses.

(d) The modification of the humanities distribution requirement and of the college English requirement.

(e) The modification of the form of the

science distribution requirement, (f) The modification of the college foreign language requirement.

(g) The adjustment of the ROTC programs to the proposed calendar.

(h) The adjustment of the Great Issues course to the proposed calendar.

Except where a specific recommendation for change is made it is to be understood that the continuation of present arrangements is recommended. For example, the degree requirement in physical education would be unmodified. It has not been thought necessary to spell out the many changes of form (as distinct from substance) of regulations that must accompany the calendar change.

Each of the proposals for immediate action will now be discussed in turn.

(a) The Three-term, Three-course Calendar

The three-term, three-course calendar is recommended to the Faculty as the most satisfactory way of reducing the subdivision of student attention implicit in five simultaneous courses without incurring the drastic reduction in the number of electives implicit in a change to a four-course semester program. The reduction in the number of courses taken simultaneously does not guarantee the introduction of coherent and rigorous projects of independent work but it makes them more feasible by reducing the multiplicity of demands upon the student's time.

The 38-40 class hours available in a term course are not significantly fewer than those available in a semester course at the present time. If it proves feasible to schedule hour examinations at hours additional to those in regular use for other meetings of each course, as recommended by the Division of the Sciences, the difference between the number of class hours in the term and the semester might be dismissed as negligible. However, the total amount of student time available for the individual course during the term is very substantially greater than that available for the individual course during the present semester. There is, therefore, a quantitative as well as a qualitative reason for thinking it will be possible to make the term course more substantial than the present semester course.

We have found it difficult to assess the validity of the argument that the more gradual assimilation made possible by the greater extension in time of a semester course (plus its intervening - and interrupting recesses) is a significant educational asset. Our canvass of opinion in some seventeen colleges and universities (including several which had changed calendars rather recently) did not encourage the belief that this was an important factor in the balance sheet of experience at these institutions. It is perhaps unnecessary to stress that the joint committees would not advocate a three-term system without a reduction to three of the number of courses carried; most institutions with experience of the term or quarter system have programs of four — or even five - courses so that the remarkably even balance of their judgments as between semester and term systems is based on a comparison lacking an important feature of the program we propose.

The adoption of the proposed new calendar reduces by three (from 40 to 37) the number of courses required to fulfill the degree requirement. To offset the consequent reduction in the number of electives available, the joint committees recommend that any student achieving a certain scholastic average shall be allowed, in the course of his four years in college, to take up to two extra courses without additional charge. The grade criterion to be applied, the period on which the scholastic average should be based, and other details of operation require consideration by experts, but the committees have in mind a "hurdle," reasonably straightforward in application, that would qualify something like the upper half of each student class....

(b) The Program of Independent Reading

The deep affection of the average college student for the assimilation of knowledge by means of a well-organized textbook has produced the American textbook industry; the quality as well as the volume of its products are the envy of the rest of the civilized world. A less happy by-product of this affection is a concomitant aversion, not universal but regrettably widespread, to the perusal of books aimed less directly at the campus, though written by men of unchallenged distinction. The objective of the program of independent reading is to combat this aversion in a modest way by requiring every student to read a selection of these books, while giving him a fair range of choice.

In the program of general reading to be completed in the first two years, some of the books might incidentally take care, in part, of some of the sampling of disciplines that is desirable before concentration is begun, thus contributing to one of the functions of the distribution requirement. The program of independent reading, moreover, will help to offset the loss of electives. The selection of books for the list from which the student would make his own choice would be made with an awareness that the books would often be read without access to faculty advice or library facilities, and in the hope that their reading would increase rather than diminish the appeal of reading as a legitimate activity of the college student. Without compromising intellectual distinction, "readability" would clearly be regarded as a virtue. The task of selection would draw directly or indirectly on the judgment of many members of the Faculty, even though the fruit of their general rather than their professional reading would frequently be involved; books defying departmental classification might often be very appropriate. The range of good books, both new and old, now available as paper backs, might be expected to be very helpful. The possibility of allowing students under specific circumstances to offer their own reading lists would have to be considered, with due regard to the complications this might entail.

Orientation lectures on some or most of the books might be made available at an appropriate time on a strictly optional basis to students desiring guidance in their choice to supplement that which they might seek from individual teachers. The method of examination of such a large number of students in inevitably diverse areas presents genuine difficulties, but they should not be insurmountable; an educational procedure may be valuable, even though the testing procedures it requires may be open to technical criticism. The temptation to defer the reading until a week or two before the examination would presumably be impressive; there are, however, campus spectacles more repulsive than a last-minute nocturnal seminar at the Alpha Omega house on MediaevalPeople, The Magic Mountain, The Human Use of Human Beings, or Scienceand the Modern World. While the resolution with which some students oppose the machinery of education must not be underestimated, it is reasonable to expect that a significant and useful fraction - one even dares to hope a large majority — of the student body of a less intransigent disposition would benefit.

The program of independent reading for junior and senior years would be organized and administered by the individual departments for their majors. The form and timing of the program might be expected to vary from one department to another. The books would naturally be more specialized than those selected, for the first two years, but it would be hoped that the reading list would include books of enduring value and some literary distinction.

In conformity with the principle that self-education is an important goal, the rewards for excellence and the penalties for inadequacy in both independent reading programs would have to be such as to discredit the assumption that they constituted an unimportant side show in the curriculum. ...

(c) The Continued Exploration of Divisional Courses

The March report recommended the establishment of certain divisional courses, namely Western Civilization 1A-2A, 1B-2B (compulsory), Social Science 1 (compulsory), Social Science 2 (optional), Science 1-2, Science 3-4 and Science 5-6 (all three optional). Some of these courses were regarded with misgiving by many members of the Faculty. With reference to the Western Civilization block, the notion of compulsion and the psychology of the large captive audience, the lack of clear definition of the machinery of the relation of the two courses (even if the intellectual counterpoint was clear), and the lack of flexibility that a four-course block imposed on one of the student's four years of study all contributed - in varying degrees for individual members of the Faculty —to a strongly Missourian attitude toward the proposal.

The Humanities Division is believed to be in sympathy with divisional courses in principle and the recommendations under (d) are, in fact, largely based on the recommendations of an ad hoc committee of that Division. The deliberations of the Social Science Division during the last semester in reviewing the explorations of the possible form of divisional courses in the Social Sciences by a Divisional ad hoc committee make it clear that the Division has little hope of devising any effective divisional course at the present time. In the Science Division three ad hoc committees are at work "to explore the best way of achieving the objectives implicit in the proposed courses designated as Science 1-2, Science 3-4, and a possible similar course in the Earth Sciences" but have not yet reported to the Division, although the terms of reference of the committees indicated the sympathetic interest of the Division in the objectives of the courses proposed.

Taking all these facts into consideration, the joint committees believe that no useful purpose would be served by proposing any compulsory courses "constructed in a divisional spirit" at this time. They recommend, however, with undiminished conviction, the energetic exploration of such courses on an optional basis and the institution in the near future of such courses as meet with divisional approval as further options in the groups of courses fulfilling the distribution requirement. ...

(d) The Modification of the HumanitiesDistribution Requirement and of theCollege English Requirement

In their thinking on the problem of the distributive requirements in the Humanities Division, the joint committees have been greatly aided by suggestions coming, in part, from individuals within that Division but, for the most part, from the work of an ad hoc committee which was established by the Division to consider this problem. The most important substantive change recommended by the adhoc committee received wide support in the Humanities Division at large, and it has been favorably viewed by the joint committees also. This recommendation involves an increase in the distributive requirements in Humanities from two to three. Coupled with this proposal was the suggestion that students be required to take two of these requirements in the form of a "double" or "sequential" course. It was felt that students ought to be expected not only to "sample" several fields in the Humanities but that they ought to be exposed in a more sustained way to at least one area. It is believed that this is essential if the student is to get more than superficial acquaintance with the distinctive concerns and methods of the Humanities disciplines. The ad hoc committee, and others within the Division, have given considerable thought to the nature of such "double" courses, and have tentatively approved two. One, which we might call Hu- manities 1-2, would be similar to the present Humanities 11-12, except that it would contain more "history" and it would not attempt to cover such an extensive historical period. The other, which we might call Humanities 3-4, would consider the major religious traditions of the West in relation to certain major philosophical movements and problems. The third course in the Humanities distributive requirement would be selected from a group of appropriate courses in the fields of Art, Classical Civilization, Music, Philosophy, Religion, and the Foreign Literatures. ...

At the present time students who are exempted from English 1 because of proficiency may elect English 3 in partial fulfillment of the distributive requirement in Humanities. The joint committees believe this policy should continue but would extend it in a different form to a larger number of students. [The recommendation that students getting a grade of B or better in English 1 be exempted from English 2 was revised by Faculty vote to "the granting of exemption from English 1 of approximately one-fourth of the entering class, these men to be enrolled in English 2 the first term. The remainder will take English 1 the first term, followed by English 2 either the second or third term. The Department of English may exempt from English 2 any student it finds qualified on the basis of his work in English I. The normal proficiency policy is not affected."]

This modification of the English requirement is recommended to the Faculty in the belief that a student getting a high grade in English i can write more than adequately, provided that it is expected of him and provided that he is given ample opportunity in his upperclass courses to practice the craft. Without such practice and without continued empirical evidence that sound prose is valued and rewarded outside the walls of Sanborn House, no college English requirement, however extensive, can be even moderately effective. ...

(e) The Modification of the Form of the Science Distribution Requirement

The modification of the science distribution requirement described in the March report proved acceptable to the Division of the Sciences with the proviso (omitted inadvertently from the original report) that not more than two courses in a single subject could be used to fulfill the requirement and with safeguards against undue delay in the completion of distribution requirements. It is accordingly recommended by the joint committees that the science distribution requirement be fulfilled by four courses drawn from the list on page 55 of "Regulations and Courses, 1956-57," together with any further new courses which may later be approved, subject to the following rules:

(a) Courses must be selected from atleast two of the following three areas: (1) Mathematics; (2) Astronomy, Chemistry, Physics; (3) Botany, Geology, Zoology. For the purpose of this rule, Science 12 shall be counted as in area (2).

(b) At least two terms shall be taken as sequential courses within a department; the two courses need not be taken in consecutive terms. For the purpose of this rule a combination of courses in botany and zoology or one of the new two-term sequences being explored at present by divisional committees shall count as being within a single department.

(c) At least one of the lour courses shall include laboratory work or small group demonstrations at which there is opportunity for discussion.

It would be quite misleading to suggest that this modification of the science distribution requirement constitutes a major change. At least nine out of every ten students at present conform to the modified regulations proposed; their adoption will, however, eliminate occasional extremes of fragmentation on the one hand or of inadequate sampling on the other that are compatible with the present rules.

(f) The Modification of the College Foreign Language Requirement

The requirement set out in the March report is again recommended without modification:

"Proficiency should be set in terms of the equivalent of three terms of study of a language at the college level, with the expectation that most students would achieve such proficiency by the end of the second term of Freshman year. In addition to class meetings the use of tape recorders or other devices for increasing oral-aural facility with or without direct supervision by a teacher would be required."

It is hoped that the three-course program with four class meetings per week and the possibility of additional regular language "laboratory" periods might be found particularly favorable to the accelerated achievement of a minimum standard of mastery of a foreign language.

(g) The Adjustment of the ROTCPrograms to the Proposed Calendar

The three service programs are continued as an integral part of the college curriculum. [ln brief summary of this section, the report recommends that ROTC studies be accorded the same total time as at present, that three-fourths of the courses or hours required for ROTC count toward the A.B. degree, that ROTC cadets therefore be required to take 39 courses, instead of 37, to fulfill the degree requirements, and that non-credit drill be held for two hours each week for the entire three-term year. Each ROTC student may take, in addition to the 39 courses, up to two additional elective courses, without payment of additional charges provided he meets certain academic qualifications.]

(h) The Adjustment of the Great Issues Course to the Proposed Calendar

It is proposed that the Great Issues course should meet twice weekly throughout the senior year and should count for credit as a single course. The obligation to write a journal covering the lectures, a device whose effectiveness seems to be generally recognized, would continue throughout the year, but all other written assignments would be confined to the first two terms. The Great Issues course would constitute an extra (or fourth) course throughout the senior year; the weekly workload would be well below that of other courses and particularly so during the final term. This proposal for the Great Issues course is in accordance with the recommendation made last year by the Great Issues Steering Committee.

GUIDEPOSTS FORSUBSEQUENT CHANGE

In addition to the specific proposals for present faculty action that have just been described, the joint committees wish to commend to the Faculty certain areas for exploration and experiment at the departmental and individual level. In all but one of these areas active and promising experiment is in progress in some part of the College; in some, experiment has already led to considered acceptance. The joint committees believe that a useful purpose would be served if every department and every teacher gave thoughtful consideration to the possible relevance of the following "guideposts" to the areas of instruction for which they are responsible.

The Re-examination of Courses and Major Programs by Departments

The proposed change of calendar would clearly require a careful examination of every course in the curriculum by those teaching in it. An important benefit to be derived from the new calendar would be lost unless energy and imagination were used in determining the most fruitful ways of using the increased amount of out-of-class work to raise the maturity of the course and to accelerate the progress of its students toward intellectual self-reliance.

This would also seem to be a convenient time for every department to review its course offerings as a whole and the requirements laid down for any major or majors offered by the department. It would seem appropriate to ask such questions as: Is the major as progressive and intellectually climactic as possible? Do the courses taken in senior year build consciously on those taken earlier? Are the level and the sophistication of such courses appropriate to the increased maturity of the student? Is there an unmistakable difference in intellectual rigor between the elementary, the intermediate and the advanced courses in the department? Is the order in which courses are taken in the department so varied that a progressive quality is impossible? If so, is this inevitable? Does the department, in fact, specify as prerequisites to the major the courses in its own and other departments that may be essential to a mature approach in the advanced courses of the department?

The present practices and characteristic needs of different departments are far from similar in these respects, and the joint committees have no thought of recommending a standardized or uniform approach. They are, however, deeply con- cerned that the opportunity for reassessment within each department, which would be naturally presented by a change of calendar, should not be neglected....

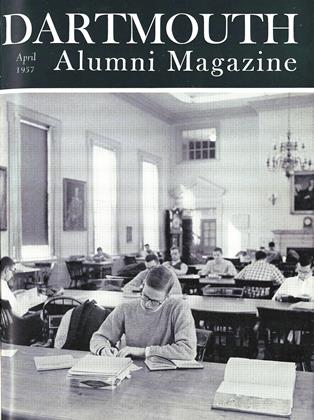

The Increased Use of Baker Library and Primary Sources of Information

The program of independent reading recommended earlier in this report is intended to play some part in familiarizing the student with the world of books. The "rich resources of Baker Library" (familiar as a phrase if not always as a reality to the Dartmouth community) are a unique challenge to the Faculty to use the potentialities of the proposed new calendar to bring the student, especially in his upperclass years, in contact with some of that wealth. The quality and quantity of the contents of Baker might well become a key weapon in our efforts to realize the ideal of shifting to the student more responsibility for his own education.

Some courses, and more particularly introductory ones, may have to lean heavily on textbooks and other well-organized digests of principles and information. Yet no faculty frequenter of the Baker stacks, no observer of its reading rooms, can have failed to experience some twinges of conscience in observing the predominant use of the extravagantly underlined textbook; he may have been led to wonder whether he himself has been as resourceful as he might have been in his own courses in promoting the progression from textbook to primary source.

In the proposed new calendar the stu- dent will have proportionately more time for work outside the classroom. The Faculty is faced with the challenge of seeing that this is used for education. Baker Library provides us with an opportunity, second to none in American colleges, of seeing to it that some of this time is spent in direct "conversation" with minds of the first rank.

The Extension of Independent Projects in the Senior Year

A number of majors in a number of departments at Dartmouth already carry out a piece of individual and independent work during their senior year. It is the opinion of many with experience of this type of enterprise at Dartmouth and elsewhere that it evokes from the student qualities of resourcefulness and intellectual maturity that are not always suspected. The joint committees suggest that departments consider whether the practice could profitably be extended to more and, perhaps, to all seniors.

Subjects undoubtedly vary considerably in the degree of sophistication to be attained before intelligent investigation is possible, and die argument for the extension of such work by seniors does not rest on the output of research findings that might be expected. There is, however, some reason for thinking that the educational value of such work does not vary directly with the scholastic level of the student undertaking it; some students whose achievement in regular courses is quite mediocre.find a unique challenge in the "Lindbergh" quality of an individual investigation and surpass all expectation in their performance....

The Introduction of Reading Coursesfor Credit

Another method of encouraging intellectual independence and the responsibility of the student for his own education might be the establishment on the initiative of departments or individual teachers of a number (presumably quite limited to begin with) of reading courses for credit. Each of these would deal with a topic or field, chosen for its significance and for the circumstances that it had been well treated in the literature and that it could be brought to a rather definite focus through a term's reading. ...

These courses would not be "research courses in any sense nor would they necessarily be of a specialized nature. 7 hey might present a challenge to able students who are frustrated by lecture courses adhering rather closely to material already available in print. This seems to be a promising field for individual experiment; the successful operation of a few rigorous courses of this sort might make a contribution to the curriculum and the sense of student responsibility much more than proportional to the number of students directly concerned.

Continued Explorations of the Possibilityof Raising the Over-all Student-TeacherRatio Without Sacrifice ofEducational Effectiveness

No portion of the March report was so misunderstood and, presumably, so illphrased as that dealing with class size, the student-teacher ratio, and faculty compensation. Since the final "guidepost" commended to the attention of the Faculty is based on the view that the joint committees take of these matters, it is necessary to make an effort to restate those views in a less misleading fashion. The attempt will be made with an acute and indeed horrified awareness of the dangers of misinterpretation and might perhaps begin with the statement of two nonbeliefs.

I. The joint committees do NOT believe: (a) that educational effectiveness (with any given faculty) is inevitably promoted by an increase in the over-all proportion of students to teachers; (b) that the educational effectiveness of any given instructor is inevitably enhanced if the size of his class is increased.

II. However, the joint committees DO believe: (a) that the quality of the Faculty of Dartmouth College will in the long run depend significantly on the economic status of college teachers in general and Dartmouth teachers in particular; (b) that an increase in the student-teacher ratio could lead to substantial economic gains for the college teacher and, therefore, could lead to long-range improvement of faculty quality; (c) that it is important to explore those areas where manpower can be economized without significant educational disadvantage in order to apply this manpower more generously in those areas (such as honors work) where a low student-teacher ratio is imperative. Certainly a close relationship between student and teacher is a valuable element in liberal education but a low student teacher ratio operating indiscriminately throughout the curriculum is a serious barrier to economic improvement of the teaching profession; (d) that the increase in the student population during the next twenty years, with its almost inevitable effect on the student-teacher ratio, provides an independent argument for resourceful exploration of ways in which teaching manpower can be used most effectively.

On the basis of these beliefs the joint committees urge upon the Faculty the value of and the pressing need for the scrutiny of all methods available to achieve true economy in the use of teaching manpower. Economies, even true ones, have a way of lacking immediate appeal; in this particular instance the benefits would be indirect, undramatic, and perhaps delayed. They could, however, be cumulatively considerable and enduring.

The scrutiny recommended can be carried on only at the departmental or, less frequently, the divisional level. A careful review of the number of course offerings and of class sizes is one of the most obvious lines of reconnaissance. Experiments carried on lately by several departments on their own initiative in the direction of replacing sectioned introductory courses by lecture-precept methods have been encouraging both in their enterprise and their results. Another device which can be helpful in promoting a more effective use of teaching resources is that of offering some of the more advanced courses in alternate years, except where the subject matter is so rigorously sequential as to exclude the possibility; such an arrangement can lead to a welcome diversification of the teaching load as well as diminishing the frequency of occurrence of small classes, whose limited enrollment is not demanded by educational needs.

The feasibility of these and other arrangements that may suggest themselves to members of the Faculty must be examined at the departmental level where the idiosyncrasies of the subject matter and the special skills of its teachers are understood. If the principle is generally accepted that the educational economy in its broadest sense is a faculty concern, the joint committees have every confidence that the necessary explorations and experiments will go forward with vigor and imagination.

A program of general reading for all students is a key feature of the new curriculum.

Independent work, using the rich resourcesof the Baker Library, is a broad objective.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

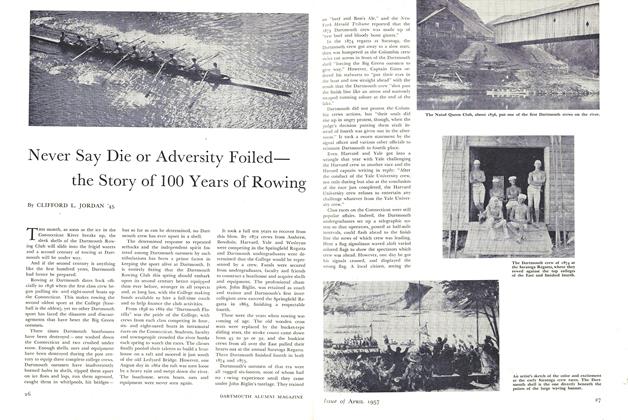

FeatureNever Say Die or Adversity Foiled the Story of 100 Years of Rowing

April 1957 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni to Honor Richard Hovey

April 1957 -

Feature

FeatureMemories of Hovey

April 1957 By EDWIN O. GROVER '94 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

April 1957 By JOHN H. RENO, WILLIAM F. STECK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

April 1957 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, THEODORE D. SHAPLEIGH

Features

-

Feature

Feature1923 – Great Class of a Great College

JULY 1973 By Charles J. Zimmerman '23 -

Feature

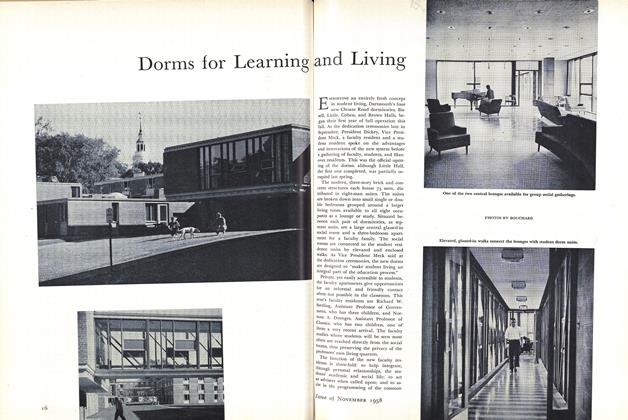

FeatureDorms for Learning and Living

By J. B. F. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Bunch Of Characters

JANUARY 1997 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Feature

FeatureFour-Star Summer

October 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureHow Much Government?

March 1954 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Feature

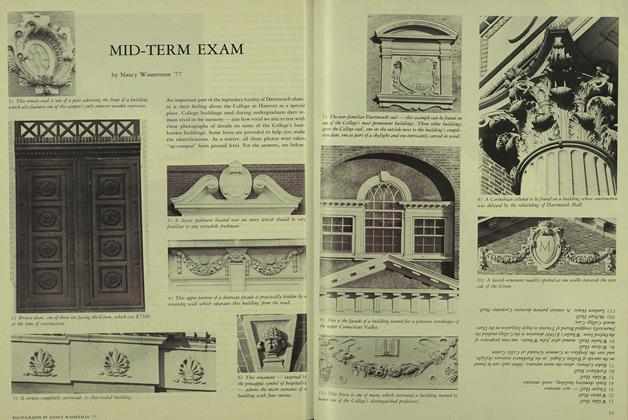

FeatureMID-TERM EXAM

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 By Nancy Wasserman '77