Never Say Die or Adversity Foiled the Story of 100 Years of Rowing

April 1957 CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45Never Say Die or Adversity Foiled the Story of 100 Years of Rowing CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 April 1957

THIS month, as soon as the ice in the Connecticut River breaks up, the sleek shells of the Dartmouth Rowing Club will slide into the frigid waters and a second century of rowing at Dartmouth will be under way.

And if the second century is anything like the first hundred years, Dartmouth had better be prepared.

Rowing at Dartmouth dates back officially to 1856 when the first class crew began pulling six- and eight-oared boats up the Connecticut. This makes rowing the second oldest sport at the College (baseball is the oldest), yet no other Dartmouth sport has faced the disasters and discouragements that have beset the Big Green oarsmen.

Three times Dartmouth boathouses have been destroyed - one washed down the Connecticut and two crushed under snow. Enough shells, oars and equipment have been destroyed during the past century to equip three complete college crews. Dartmouth oarsmen have inadvertently burned holes in shells, ripped them apart on ice floes and logs, run them aground, caught them in whirlpools, hit bridges but so far as can be determined, no Dartmouth crew has ever upset in a shell.

The determined response to repeated setbacks and the independent spirit fostered among Dartmouth oarsmen by such tribulations has been a prime factor in keeping the sport alive at Dartmouth. It is entirely fitting that the Dartmouth Rowing Club this spring should embark upon its second century better equipped than ever before, stronger in all respects and. at long last, with the College making funds available to hire a full-time coach and to help finance the club activities.

From 1856 to 1862 the "Dartmouth Flo- tilla" was the pride of the College, with crews from each class competing in four-six and eight-oared boats in intramural races on the Connecticut. Students, faculty and townspeople crowded the river banks each spring to watch the races. The classes finally pooled their talents to build a boathouse on a raft and moored it just south of the old Ledyard Bridge. However, one August day in 1862 the raft was torn loose by a heavy rain and swept down the river. The boathouse, seven boats, oars and equipment were never seen again.

It took a full ten years to recover from this blow. By 1872 crews from Amherst, Bowdoin, Harvard, Yale and Wesleyan were competing in the Springfield Regatta and Dartmouth undergraduates were determined that the College would be represented by a crew. Funds were secured from undergraduates, faculty and friends to construct a boathouse and acquire shells and equipment. The professional champion, John Biglin, was retained as coach and trainer and Dartmouth's first intercollegiate crew entered the Springfield Regatta in 1863, finishing a respectable fourth.

These were the years when rowing was coming of age. The old wooden cross seats were replaced by the bucket-type sliding seats, the stroke count came down from 45 to 30 or 32, and the huskiest crews from all over the East pulled their hearts out at the annual Saratoga Regatta. There Dartmouth finished fourth in both 1874 and 1875.

Dartmouth's oarsmen of that era were all rugged six-footers, most of whom had no lowing experience until they came under John Biglin's tutelage. They trained 0n "beef and Bass's Ale," and the NewYork Herald Tribune reported that the 1873 Dartmouth crew was made up of "raw beef and bloody bone giants."

In the 1874 regatta at Saratoga, the Dartmouth crew got away to a slow start, then was hampered as the Columbia crew twice cut across in front of the Dartmouth shell "forcing the Big Green oarsmen to give way." However, Captain Gates ordered his stalwarts to "put their eyes in the boat and row straight ahead" with the result that the Dartmouth crew "shot past the finish line like an arrow and narrowly escaped running ashore at the end of the lake."

Dartmouth did not protest the Columbia crews actions, but "their souls did rise up in angry protest, though, when the judge's decision putting them sixth instead of fourth was given out in the afternoon." It took a sworn statement by the signal officer and various other officials to reinstate Dartmouth to fourth place.

Even Harvard and Yale got into a wrangle that year with Yale challenging the Harvard crew to another race and the Havard captain writing in reply: "After the conduct of the Yale University crew, not only during but also at the conclusion of the race just completed, the Harvard University crew refuses to entertain any challenge whatever from the Yale University crew."

Class races on the Connecticut were still popular affairs. Indeed, the Dartmouth undergraduates set up a telegraphic system so that operators, posted at half-mile intervals, could flash ahead to the finish line the news of which crew was leading. Here a flag signalman waved aloft varied colored flags to show the spectators which crew was ahead. However, one day he got his signals crossed, and displayed the wrong flag. A local citizen, seeing the flag, promptly made a sizable bet with an unwary victim who did not understand the flag code. However, when the crew whose flag had been waved aloft did not even finish, the very irate citizen discovered the mistake and promptly heaved the flagman, flags and all, into the river.

Even in those early days funds were needed for the sport and it is reported that in 1875 and 1876, E. C. Carrigan '77 visited "various towns and cities to solicit funds for rowing" and "the alumni, as usual, came through with ample funds for the continuation of the sport."

An old-fashioned spelling bee was also put on in 1875 to raise money for crew, with fifty students competing for a copy of Webster's Dictionary. Professor Sanborn "gave out the words" with Professors Parker and Quimby acting as judges. "Most of the words were quite simple," according to a writer of the day, who thereupon listed as samples: catafalque,xebec, gnomon, usquebaugh, disemboque,mignonette, assafoetida and some others that the winner, Charles Whitcomb of Boston, must have breezed through. At any rate, $91.25 was turned over to the Dartmouth Boating Association.

But this golden era terminated with abrupt finality when in January 1877 the Dartmouth boathouse collapsed under the weight of snow, and shells, oars, and equipment valued at over $2,000 were totally destroyed. At the same time Princeton, Columbia and Cornell withdrew from the New England Rowing Association and these two blows sounded the death knell for Dartmouth crews for a period of almost fifty years.

In 1879 an attempt by Wesleyan to revive a New England Boating Association with Dartmouth as a member drew this comment from The Dartmouth: "We are sorry but boating is played out here. No organization, no shells, no enthusiasm, no money. Just now Dartmouth is interested in baseball; get up a nine, Wesleyan, and Dartmouth will try to play you, but boating is too far gone to be revived."

The Dartmouth's prediction held good until the early 1920's, when various efforts were made to revive rowing - all unsuccessful. In the next decade, however, student interest was sufficiently aroused so that by 1933-34 several shells were secured and an old ice house donated by the Enfield Improvement Society on Lake Mascoma was converted into a boathouse. The first organizational meeting was held in April 1934, and more than 160 students turned out to hear Jim Smith of the Union Boat Club at Boston, who had come up to coach Dartmouth, say: "All you need for rowing is two arms, two legs and a certain amount of guts."

On April 26, 1934, Mrs. Ernest Martin Hopkins christened two new shells — the Phillips and the Ledyard by pouring waters from Lake Mascoma and the Connecticut across their prows before some 2,000 students and townspeople. After fifty years another Dartmouth crew took to the water.

Austen Lake, reporting on the ceremonies in The Boston American, commented - "There is something dangerously communistic about the way Dartmouth has launched its new Navy on Mascoma Pond, something that strikes at the very taproots of the college social system, sets up a rebellious example and threatens the sanctity of a sport that has always been the gewgaw of quality classes ... for Dartmouth has floated its own boats from its own boathouse and has a competent coach without spending a shilling This is an impertinent violation of the college rowing code which calls for a life of oriental luxury.... Well then here comes Dartmouth with a couple of secondhand shells with their bottoms patched, an abandoned ice house on a wilderness pond, and a tatterdemalion squad of candidates in corduroy breeches. And they go to barefaced rowing, aheaving and ayanking on their hoehandles like ragamuffins on a raft. O ho! They do, do they?"

Spring intramural races between the Phillips and the Ledyard, chiefly the big Memorial Day Races, were the features of the era from 1934 to 1937. An intercollegiate race was held in 1936 between Dartmouth and Cornell at Ithaca, with the Big Green losing.

By 1937 Dartmouth rowing was growing stronger and the crews shifted back to the Connecticut River. There on Green Key weekend, President Hopkins dedicated the Alvan T. Fuller Boathouse - named after the former Governor of Massachusetts formally launched two new Dartmouth shells and fired the starting gun for a race against Williams College, which Dartmouth won by two lengths.

Rowing had finally returned to the College. Writing in The Dartmouth the day of the Williams race, Robert L. North '39, spoke for many when he said: "The Dartmouth crew rows today because it had the guts to fight the opposition and financial indifference of die-hard skeptics, because its members sold peanuts at football games, and have worked months in the gymnasium even when they were not sure of replacing wrecked equipment... and when the Indian oarsmen slip their slim cedar shells into the water this afternoon, they will pass a milestone, far more important than any athletic achievement, a milestone expressive to the College of what student initiative can accomplish when guided by enthusiastic, capable leadership."

A year later, with Jim Smith still coaching, Dartmouth was admitted to the Eastern Association of Rowing Colleges and in 1939 the first Dartmouth varsity crew competed in the Dad Vail Regatta, finishing fourth. The same year letter awards were granted for the first time, and in 1940 freshman numerals were added.

Dartmouth rowing was gaining by leaps and bounds. In 1941 the sleek, new shell - the Ernest Martin Hopkins - was dedicated, and even the war years could not slow up the rowing club, as the Dartmouth Navy took over.

By 1946 Dartmouth crews were back on the water, finishing second in the 1947 Dad Vail Regatta and third in 1948, 1950 and 1952. Dartmouth's first crew went to the Henley Regatta in England in 1950, and another crew went in 1955. In 1952, Dartmouth's JV crew retired their trophy after three successive Dad Vail victories.

Dartmouth rowing needed this firm foundation for on March 12, 1952 the boathouse collapsed under heavy snows, crushing five eight-oared shells valued at over $6,000 and some $2,000 worth of other equipment. Luckily the Dartmouth oarsmen "dug out," the College rebuilt the boathouse for them, Columbia led a fund campaign among Eastern rowers for funds, several sister institutions donated shells or sold them to Dartmouth at low cost, alumni and friends responded with generous gifts of money and equipment, and within a year, the Dartmouth Rowing Club was back in business, stronger than ever.

Construction in 1951 of the Wilder Dam, two miles downstream from the Ledyard Bridge, turned the turbulent Connecticut River into placid "Wilder Lake" and permitted the Rowing Club to lay out an "almost perfect Henley course." Professor Marshall Robinson coached the 1952 and 1953 Dartmouth crews, with Thaddeus Seymour, an English instructor and former Princeton varsity oarsman, taking over in 1954. Dartmouth's 1954 varsity heavyweight crew went undefeated to win their first Dad Vail Trophy, and the following year the Indians swept all three events at the Dad Vail. Last year Dartmouth moved into the "big time" in Eastern rowing, competing for the first time in the E.A.R.C. Sprint Championships and the I.R.A. Regatta, and also entered a four-oared shell in the Olympic trials.

This spring, the Dartmouth Rowing Club faces the heaviest schedule ever attempted, meeting the top collegiate crews in the nation at the I.R.A. Regatta and E.A.R.C. Sprints. Indeed, Dartmouth oarsmen will be competing against the mighty Yale crew which this past year won the Olympic crown - a far cry from the "tattered" crews which took to Mascoma Lake in 1934.

Things may be going a bit too smoothly for Dartmouth crews. We expect any day to hear that lightning has struck the boathouse, burning everything to ashes, that the club treasurer has absconded with all the funds, that the new coach has been transferred to the Romance Languages Department... then we'd be certain that rowing at Dartmouth was starting off its second century on the right foot!

An artist's sketch of the color and excitement at the early Saratoga crew races. The Dartmouth shell is the one directly beneath the points of the large waving banner.

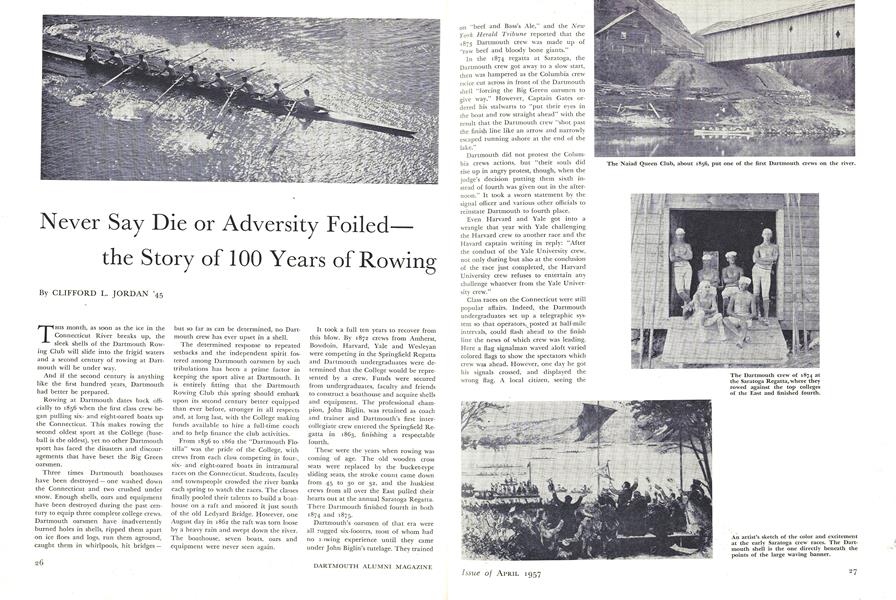

The Naiad Queen Club, about 1856, put one of the first Dartmouth crews on the river.

The Dartmouth crew of 1874 at the Saratoga Regatta, where they rowed against the top colleges of the East and finished fourth.

The 1950 crew, the first to be invited to the famed Henley Regatta.

A historic year for Dartmouth crew was 1934, when Mrs. Ernest Martin Hopkins (center) christened two new shells to mark the revival of rowing on nearby Lake Mascoma.

Jim Smith (r), who came from the Union Boat Club of Boston to coach the Dartmouth oarsmen in 1934, shown with Jack Unkles '52 and the Dad Vail Trophy won by the Dartmouth junior varsity crew in spring of 1950.

The third major catastrophe in the history of Dartmouth crew occurred in March 1952 when the boathouse collapsed under a heavy snowfall. Everything was lost but, as before, rowing came back stronger than ever.

Coach Thad Seymour (left), who has led Dartmouth into "big time" rowing, with Hart Perry, club head in 1955.

The "Dartmouth Flotilla" of today, out in full force on the Connecticut River.

The Fuller Boathouse, recently enlarged to house a growing fleet.

The 1955 lightweight crew which went to the Henley Regatta.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA New Educational Program

April 1957 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni to Honor Richard Hovey

April 1957 -

Feature

FeatureMemories of Hovey

April 1957 By EDWIN O. GROVER '94 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

April 1957 By JOHN H. RENO, WILLIAM F. STECK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

April 1957 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, THEODORE D. SHAPLEIGH

CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45

-

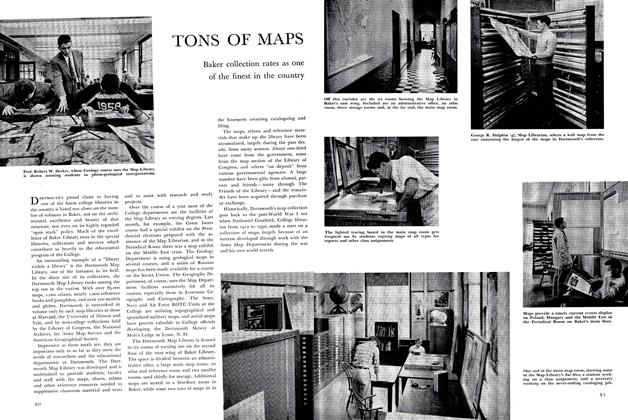

Feature

FeatureTONS OF MAPS

December 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksALASKA SOURDOUGH:

February 1951 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund Plans for 1958 and 1959

January 1958 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

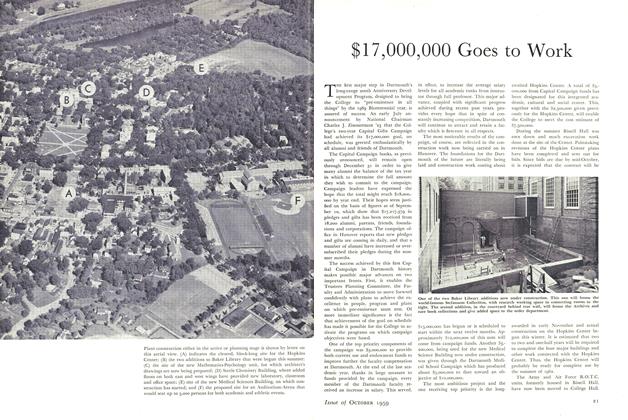

Feature$17,000,000 Goes to Work

October 1959 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleThe Russian Review's 20 years

February 1962 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Cold, Cold World of CRREL

FEBRUARY 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Transcending Great Issues

OCTOBER 1969 -

Feature

FeatureA Spot of Green at Knob Lake

March 1958 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Features

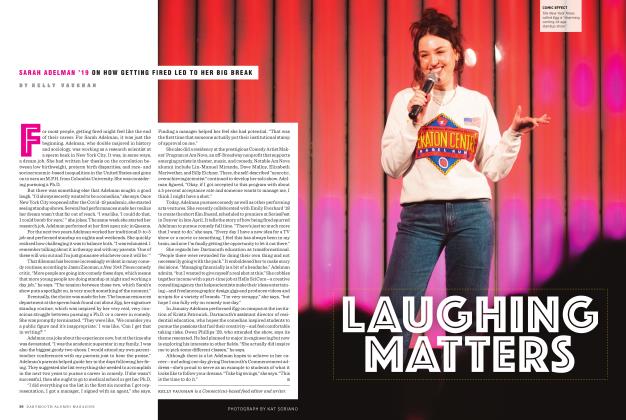

FeaturesLaughing Matters

MAY | JUNE 2025 By KELLY VAUGHAN -

FEATURE

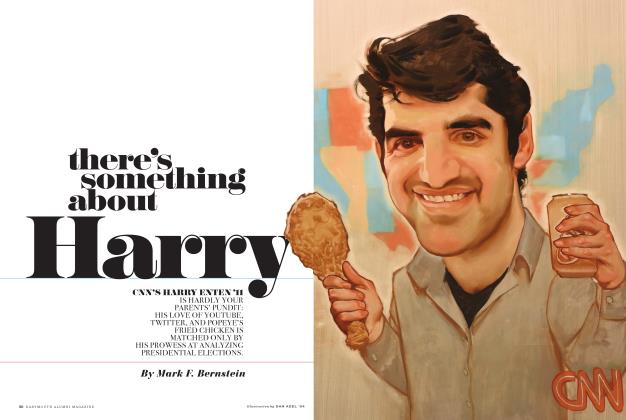

FEATUREThere’s Something About Harry

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2019 By Mark F. Bernstein -

Feature

FeatureWILL TO RESIST

APRIL 1969 By RICHARD W. MORIN '24 -

Feature

FeatureA Student Address

JULY 1970 By WALLACE L. FORD II '70