PROVOST OF THE COLLEGE

No student ever was saved by a curriculum." This sage observation by Professor L. B. Richardson, made in 1946 as the faculty debated proposed changes in the curriculum of which he was the architect, has come to mind often during the last decade. It is a reminder, if one is needed, that the mechanics of education are less important than teachers and students. Dedicated teachers, looking beyond this truth, feel obligated to search for better ways of helping undergraduates become educated men.

Self-criticism is painful, and when the customs of a profession and a complex academic program are involved, patience is required of all hands. From 1946 to 1957, literally thousands of hours were given to re-examining basic educational philosophy, courses, and teaching methods. The immediate results of this prodigious effort, summarized in this issue, have now been approved by the general faculty for transmittal to the Board of Trustees.

What will be the significance of these changes? Will they really make a difference in the quality of the undergraduate's educational experience? Will they strengthen Dartmouth's ability to maintain a first-class faculty? Enable her to be more responsive to the needs of society? Final answers to these questions will be given by future generations of Dartmouth men. Immediate answers may be sought in some of the circumstances out of which the proposals have grown.

On the national scene, institutions or higher education face a challenge that is either frightening or exciting, depending upon our reaction. First, die erosion of educational resources by inflation has been great and is continuing. Second, all the indicators point to fewer college teachers relative to the number of students, and fewer first-rate teachers relative to the total number of teachers. Third, since the quality of education depends ultimately upon the quality of teachers, an essential sector of national well-being is at stake.

Is there a promising strategic approach to the resolution of this national problem?

In most colleges, the emphasis today is on the student's learning what he istaught. This expectation requires no rude break in habits begun in elementary grades and strengthened in secondary school. It fits in well with textbooks, weekly classes and quizzes, hour and final course examinations, required attendance, and other established routines.

But does this approach produce the best motivation for self-education, which must extend beyond (but not begin with) Commencement? Does it accelerate or retard intellectual maturity in college students? Does it require of the teacher busy work that is educationally unproductive, at the sacrifice of more rewarding activities?

Suppose the focus is shifted from teaching to learning, and colleges begin to think of their task as one of enablingstudents to learn without being taught. If, as most of us believe, the only education worthy of the name is self-education, this concept of teaching is imperative. It could not, of course, become immediately and equally effective for all college students.

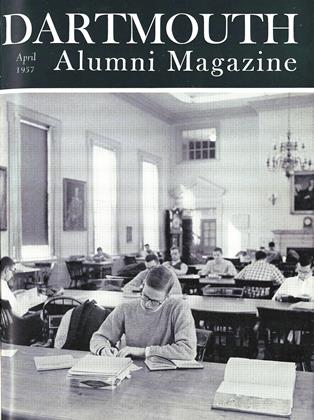

But as students grew in capacity for selfeducation - as they would surely do if it were expected of them - college campuses would be transformed. Libraries would become important to all students, as repositories of the visual aids called books and not simply as sanctuaries from noisy dormitories or social centers for the intermingling of the sexes. The more competent undergraduates could help with the instruction of less advanced students, to the mutual advantage of students and teachers. Students would spend more time preparing for meetings with their teachers, and less time in the classroom. Whether preparing for a class or an examination, the significant question would be What do I think?, not What does the book or the professor say? It is even possible that it would be considered wasteful for students to be on vacation about forty per cent of their four college years.

At Dartmouth these ideas are not new or untried. Senior Fellows spend an entire year in independent study, with Baker Library the operating center of their educational experience. Class of 1926 Fellows combine a summer and a semester of residence in Washington for first-hand and self-directed study of public affairs. During the next few years we hope to extend to many the advantages now given to these few, and to enlarge for all the opportunities for achieving independence in learning. In such an atmosphere, education would be a cooperative venture of student and student, and of student and teacher, rather than a competition between student and teacher to see which can outguess the other.

As we move toward this objective, it should be possible for the teacher to use his talent and influence selectively —at critical points in the student's learning experience - instead of exhausting precious energy where it is not really needed. In exploring possibilities for extending the creative influence of teaching, curricular organization and teaching methods will need to be reconsidered. But if real progress is to be made, the question of how the' student spends his time is at least as important as the question of how the teacher spends his.

In short, we are seeking to improve greatly the student's educational experience in ways that will require less of the teacher's time and energy. This is an exciting prospect, in which there is increasing national interest.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA New Educational Program

April 1957 -

Feature

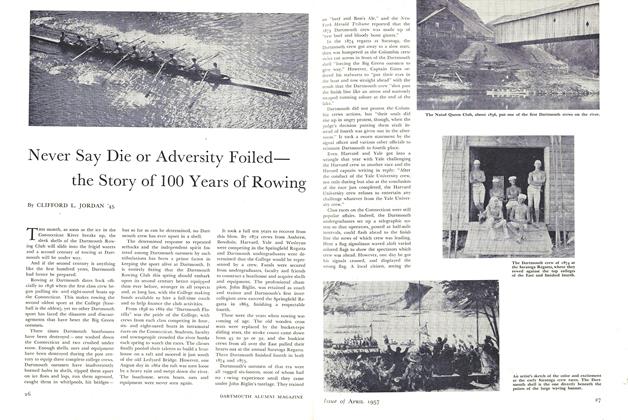

FeatureNever Say Die or Adversity Foiled the Story of 100 Years of Rowing

April 1957 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

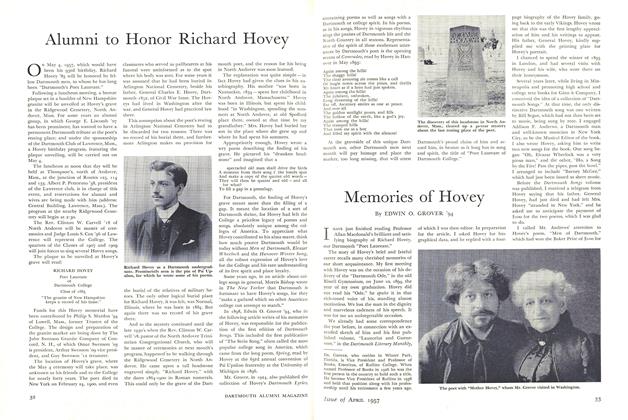

FeatureAlumni to Honor Richard Hovey

April 1957 -

Feature

FeatureMemories of Hovey

April 1957 By EDWIN O. GROVER '94 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

April 1957 By JOHN H. RENO, WILLIAM F. STECK

DONALD H. MORRISON

-

Article

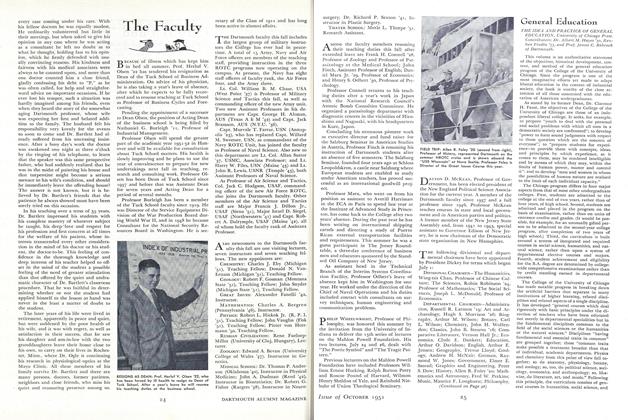

ArticleGeneral Education

October 1951 By Donald H. Morrison -

Books

BooksTHE PRIVATE PAPERS OF SENATOR VANDENBERG

July 1952 By Donald H. Morrison -

Books

BooksTHE STATES AND THE NATION.

January 1954 By DONALD H. MORRISON -

Books

BooksSOLDIERS AND SCHOLARS: Military Education and National Policy

March 1957 By DONALD H. MORRISON