THE College has suddenly got a good half of an honor system with a minimum of pain and oratory. It is estimated that more than half of the first round of hour exams were given under one form or another of such a system, and there is every expectation that the second round of exams will show even more progress.

This state of affairs has been achieved through an intelligent and practical approach on the part of the UGC Honor System Committee and by the willing cooperation of a sizable portion of the faculty. The chairman of the committee, Monte Pascoe '57, sent form letters at the beginning of the semester to all faculty members asking them to employ the system on an individual basis. The letters suggested that the professors leave their classrooms after distributing their exams.

Pascoe says that more than half complied and that the response exceeded the fondest expectations of the committee. (It must be noted that a few brave professors have been trusting their students in this fashion right along.) There were three striking instances of professors making decided advances beyond the committee's suggestions: The English Department, as a department, employed the system for all English 1 exams; in other words, for all freshmen in the College. Prof. Joseph Marsh passed out his exams for Economics 14 five days before the due date. He asked only that the students indicate on their blue books the time they took, which, according to Marsh's instructions was not to exceed "one consecutive hour." Prof. Paul Shafer conducted his Chemistry 52 exam under the honor system after polling His students on their preferences. The students voted 73 to 10 for using the system, which in this ease employed a modified reporting rule - the students were to report instances of cheating but not individuals.

The Dartmouth got vigorously behind the movement, reporting these examples as they took place. It is possible that this holding up of a sort of standard by which the faculty could exercise a little self-comparison had some effect. But in one case, The D tackled Goliath, and got whipped: Great Issues would have none of this silly business of trusting the student.

Professor Shafer's modified reporting rule showed a nice foresight, if one grants that a reporting rule of some sort is necessary, and might serve as a model for any later attempt by the UGC to introduce a full-fledged honor system by referendum. The student body, as is known, rejected the honor system in 1952, and the cause was widely believed to be that system's incorporation of a compulsory reporting clause - pertaining to individuals, not just to instances of cheating.

The UGC has plans to introduce another referendum at a future date, and the purpose of the current practical approach is largely to educate students and faculty to the advantages of honor. One would hope that the UGC will keep its eye on the modest but real gains it has achieved this semester and on the possibility of getting around this truly objectionable business of reporting before it shoots the works again on a referendum which might not pass.

STUDENT reaction to the curriculum changes announced last month is largely unknown, and what reaction is known is not necessarily significant. Half the campus will never study under the new system, and the other half is lacking in experience in half or more of the present curriculum. No student, it is safe to say, is in a position to know all the facts about the new curriculum, the thinking behind it, or what it portends. And no doubt, most will depend upon the application of the program in practice.

With these reservations, then, the following sample of student opinions this writer considers responsible - from two seniors, one junior, and one freshman - is presented.

The junior said the three-term system will not succeed unless each student realizes that his education is his own responsibility. "In a program based on individual effort and initiative, the type of student who has been in the habit of drifting through college will find himself lost in a college that no longer takes on the responsibility for his education." Strong words, these last; the junior obviously considers the shift fundamental.

The freshman confessed his first impression was that the new system "certainly could be casual," that cramming would be considerably easier with only three courses, and that, for an unexplained reason, "the happy-go-lucky student could do the bare minimum of outside reading." He noted that "the educational advantages of the new system would make possible a much better and fuller education for the student who is seeking it," but he thought the emphasis on learning would dictate a closer scrutiny of applicants for admission "to eliminate as many students who aren't serious as possible."

One of the seniors had no good words for any part of the plan. He said of two justifications given for the change, one is the result of wishful thinking and the other a denial of the value of liberal education. The first justification he called "shifting the emphasis from teaching to learning" and said it could never be accomplished by mechanical changes. The answer here, he said, is newer and better pedagogical techniques - techniques that could operate within any course system. The other justification he said was saving money. "If liberal education is worth doing at all," he said, "it is worth doing well. That the proposed curriculum will lower the quality of that education is undeniable. No more time is available per course; this is just a game with numbers. And, if the College needs more money, it should get more money - by raising tuitions for one method - and not debase its present currency."

This senior bears the same credentials, and takes a directly opposite view: "I am heartily in agreement with the objective of the new curriculum - to increase the student's responsibility for his own education." He noted a "quantitative improvement" in the change from five courses to three and a desirable decrease in fragmentation of attention. Having final exams three times a year, he said, will allow better organization of material than does the twice-yearly exam system. The independent reading program, he felt, has "real possibilities." He only hoped that the machinery for checking effort in this area would be acceptable, and that the faculty would contribute "guidance on the positive side." He looked for the expansion of honors programs and seminar courses under the new system and a concurrent expansion of "survey courses on the inter- and intra-departmental models." The transition, he said, will impose strains, and the system will be only as effective as the men who are involved in it - students and faculty. "The proof is in the pudding but the new recipe looks good."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureExciting Theater Ahead

May 1957 By WARNER BENTLEY -

Feature

Feature"An Open-Arms Aspect ..."

May 1957 By ANN HOPKINS POTTER -

Feature

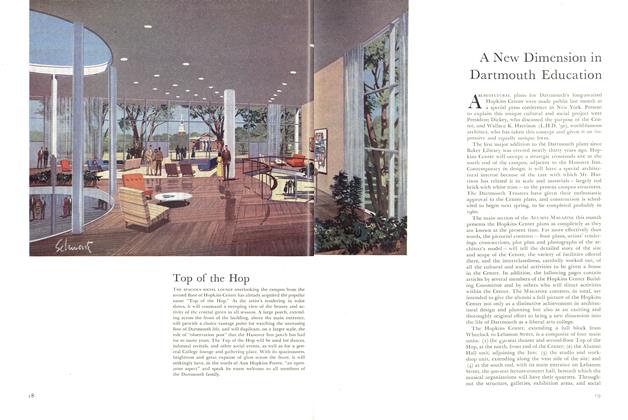

FeatureThe Man Who Designed the Center

May 1957 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Feature

FeatureDramatics

May 1957 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

FeatureA New Dimension in Dartmouth Education

May 1957 -

Feature

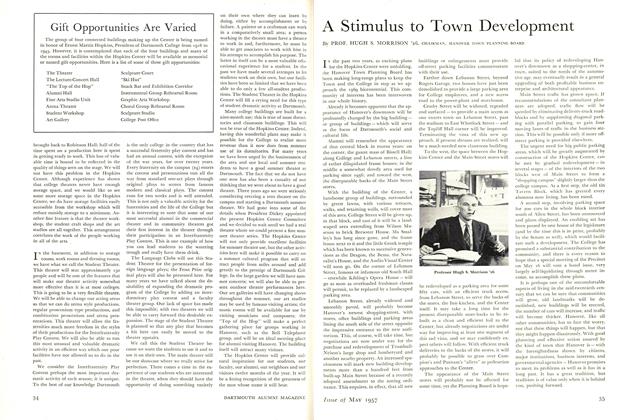

FeatureA Stimulus to Town Development

May 1957 By PROF. HUGH S. MORRISON '26,

DONALD D. MCCUAIG '54

-

Article

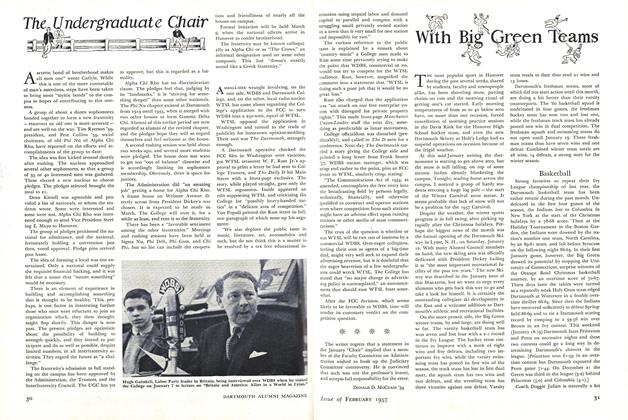

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1956 By DONALD D. MCCUAIG '54 -

Article

ArticleA Lively Ten-Year-Old

December 1956 By DONALD D. MCCUAIG '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1951 By DONALD D. MCCUAIG '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1957 By DONALD D. MCCUAIG '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1957 By DONALD D. MCCUAIG '54 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate

June 1957 By DONALD D. MCCUAIG '54

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE TO BE REPRESENTED IN INAUGURAL PARADE

-

Article

ArticleObituaries

November 1928 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

April 1944 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleLongfellow's Dartmouth Influences

March 1931 By JASON ALMUS RUSSELL '20 -

Article

ArticleNEWS AND NOTES

MAY | JUNE By Marley Marius ’17 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

January 1943 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22