WALLACE K. HARRISON, architect, is a cathedral of a man. Like his buildings, his exterior reflects inner function. He is a large man, six feet two or so, with a deep, oval face and soft, friendly eyes. His voice rustles pleasantly - quietly understating the energy that releases it: "Everything is ahead of us: The best play has not been written. The best song has not been sung. The best building has not been built."

Harrison was born in 1895. At fourteen he was on his own as an office boy in a Worcester, Massachusetts, construction company. After two years and a raise from five to nine dollars a week, he was doing his chores at a drawing board and in another two years he was a junior draftsman taking night courses in structural engineering at Worcester Tech. In 1916, the twenty-year-old Harrison went to New York and offered his services to the nation's leading architectural firm, McKim, Mead and White. There was no job open. Would they take him if he worked for nothing? In two weeks time he was a regular staff member. McKim drew on the Renaissance and during the working day the young draftsman's questions were always answered by citing tradition. At night, however, in Harvey Corbett's classes on the fourth floor over Keene's Chop House, a group of young students occasionally measured the masters and decided for themselves what was best.

In World War I, he served as ensign on Submarine Chaser 80 which managed to make its way to Europe. At the end of the war, his ship put in at Marseille and Harrison, on leave in Paris, looked in on the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts - the parent of all American schools such as the atelier atop Keene's Chop House. Immediately, Harrison set his sights for the Beaux-Arts and, after studying mathematics back at Columbia and with his Navy savings in his pocket, he returned to Paris and passed the 12-hour entrance examination. The year at the Beaux-Arts helped him to receive a traveling scholarship which, for the first time set him in front of the Old World masterpieces with time to ponder, to take measurements and make sketches. After years of study and talk about tradition he had finally touched it. The young architect who had started at fourteen finally had a point of departure.

Harrison returned to the United States in 1922 and was on his way - although the road was rough and left strewn with monuments of little consequence until 1927 when he joined the firm of Helme and Corbett as a junior partner. It was then that he started building toward greatness in earnest by measuring everything he did, not against the classics but rather against a functioning man 6' high with a seat 2' 6" wide.

THEY say he is the most influential architect of his generation. They point with pride to more than $700 million worth of his creations. They claim that no other living man could have brought together the international titans of design to act as one and create the United Nations buildings. They love his rumpled casualness. They call him a philosopher - a man of vast learning and understanding. "He seeks beauty," they say. "Wally is only concerned with truth. They quote him: "If, as Pascal said, 'The heart has its reasons,' the arts have their reasons - reasons you can't explain." And "they" (whoever they are) count him as a friend. They feel toward him in a very special way - no one, it seems, is just a friend of Harrison's. They are all his champions; they force you into a corner to tell at length what a man he is.

What part Harrison's success with people plays in his role as a successful architect is beyond measure. Every job is for people (the man with the 2' 6" seat) and by people - not just an architect or, indeed, architects. The building of the U.N. was one of the greatest triumphs in human relations of all times. As Director of Planning, it was Harrison's job to get the best from seventeen of the world's top architects and meld that best into one plan, on time and within a tight budget. His qualifications were unique: He had had vast experience with the big ones: ten years on Rockefeller Center alone. He was highly respected as an architect and as a man. He had served during World War II in government, ending up as Coordinator of the Office of Inter-American Affairs, a job that not only made use of his great talent for working with people but also gave him a real intensity for the mission of the U.N. The evidence of a job successfully accomplished is now accepted by school children from Peoria and Ministers from Pakistan. But the real force of Harrison's personality was expressed by the volcanic French architect Le Corbusier in a flush of atypical camaraderie released to the press shortly after the General Assembly accepted the plan for the buildings: "A wonderful result has been achieved," he said in a 500-word statement. "To those outside who question us we can reply; we are united, we are a team, the World Team of the United Nations laying down the plans of world architecture.. . . There are no names attached to this work. . . . Each of us can be legitimately proud of having been called upon to work in this team." "Corbu," as Harrison calls him had some second thoughts about his statement - but only after he had the ocean separating him from Harrison.

Harrison, of course, received much credit for the U.N. project and yet always went out of his way to avoid it. (Among other honors was an L.H.D. from Dartmouth in 1950.) "No man, I know," John Dickey says, "has less need for taking credit for anything than does Wallace Harrison." His drive is fed not by praise, but by the stimulus of his own creativity.

PRESIDENT DICKEY and Harrison met during the War when Mr. Dickey was an officer in the State Department. Their friendship has continued since and when the Building Committee was in the process of recommending an architect for the Hopkins Center, the President of the College leaned back to be impartial and took less and less part in the discussions. At the outset, the Committee favored Harrison among all other architects considered, on the basis of examples of his work it had seen on numerous "site seeing" visits. Ultimately the Committee recommended Harrison to the Board of Trustees and the Board sent the President of Dartmouth College to ask Wallace Harrison, architect, to undertake the job if he would be personally responsible for the whole design.

They met in Harrison's plain, businesslike headquarters in Rockefeller Center's International Building. The unadorned waiting room offers blue canvas chairs. Harrison's office is two large drawing tables and a few more chairs. There are piles of rolled blueprints, ideas on scattered pieces of scratch paper Harrison has tried out with his felt-tipped pen, and odd bits and pieces of things that he picked up from time to time because he liked them. The President explained his mission and described the concept of the Center as it had evolved through the Advisory Committee on Plant Planning, the Trustee Committee on Buildings and Grounds, the Hopkins Center Building Committee and, finally, the Board of Trustees itself. The idea of bringing the creative arts into physical proximity in a place of central importance in the life of the College appealed to Harrison immediately. The President emphasized that the College was looking for a physical facility that also would be an educational tool. The relatedness of the arts is part of Harrison's being. He constantly uses the terms of one art to speak of another. The physical facility could be a symbol of the unity of creativity. Harrison, as always, was doubtful about his ability to bring off a new idea. He said merely that he would like to try — on the condition that if he wasn't able to translate the concept into something that satisfied him, he would be free not to go any further. The planning job has taken two years of solid work. Members of the Building Committee met with Harrison frequently in New York and Hanover. Each member of the Committee knew what he wanted: each wanted his facility to be the best of its kind. Some had waited a very long time. For Warner Bentley it had been nearly thirty years since he first started dreaming about an adequate theater. And the Committee didn't lack ideas. Thousands of them flew about, hundreds came to roost on the plans.

No suggestion was received casually by Harrison; he constantly questioned to be sure that he thoroughly understood. He would think over an idea and then, perhaps, make some lines with his pen, or rework the clay model that he mused over for hours. So many changes were made that Committee members were sometimes embarrassed to suggest yet another alteration. (They didn't realize that it had taken 1,036 drawings before Harrison was satisfied with the trylon and perisphere motif for New York's World Fair.) It was always Harrison who urged them on. They were after the best, he reminded them. For his own part, he would willingly disown his brainchildren as soon as something better came along. And at times when he sensed that the solution had been found, and that further tampering could do no good, he spoke up firmly.

HARRISON made some of his best contributions over weekends at his Huntington, Long Island, home when there was leisure to think things out. Some solutions came at odd times: once at the meeting of a foundation board, on which both he and President Dickey serve, he leaned over to the President and said, "I think I have the relationship between the theater and the Top-of-the-Hop." Other things took shape on planes or over whiskey sours (his favorite). When Committee members thought that they had something just right Harrison would frequently say "We're beginning now - we can do a lot better."

But there was no dragging on. When he felt that a meeting had gone on as long as was sensible, he would rise abruptly to suggest that the next step was to get the ideas into a blueprint. At other times, in shirtsleeves, bending over his drawing table, eyes half shut against his curling cigar smoke, he would say: "We'll start again." Often, he would try out ideas on his partner Max Abramovitz, whom he regards as one of the world's outstanding designers.

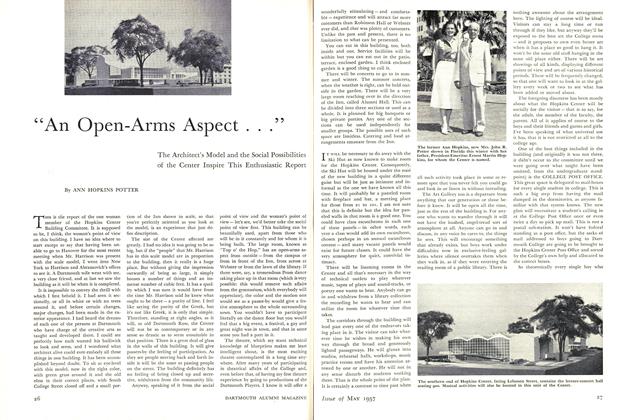

The exterior of the Hopkins Center caused him great concern. At his first meeting with the Building Committee, he spoke of Dartmouth Row as the "jewel of the campus" and said that nothing should be added to the setting to detract from it. For months, successive clay models of the Center had blank facades while he worked out just how the Center could have its own integrity and yet not compete with Dartmouth Row.

Harrison is a man of disciplined. passion. He is great enough as a creative artist to be permitted excesses in temperament. But this is not part of him; rather he seems to put all his energies directly into his work and he is left as a very easy, relaxed person. When he feels something deeply he says it - knowing that it is unusual: "People don't talk too much about what they feel... it is almost bad manners to do so." He is satisfied that the Hopkins Center is his best. Now that the concept has been developed into plans and is embodied in a model, he can see the building clearly in function as it serves the individual: "The Center will give every student who goes into it the chance to rub off a little of this idea of beauty and of culture." And then he says, with a characteristic twist, "If he doesn't rub it off on his head, he'll rub it off on the seat of his pants."

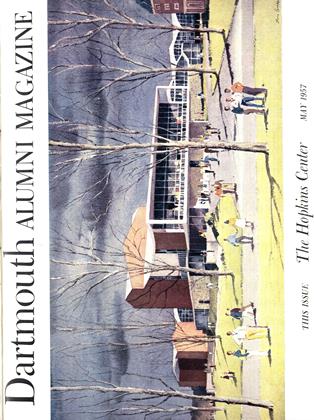

Wallace K. Harrison (r), architect, and Charles J. Zimmerman '23, chairmanof the capital gifts campaign, with a preliminary model of Hopkins Center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureExciting Theater Ahead

May 1957 By WARNER BENTLEY -

Feature

Feature"An Open-Arms Aspect ..."

May 1957 By ANN HOPKINS POTTER -

Feature

FeatureDramatics

May 1957 By PROF. HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Feature

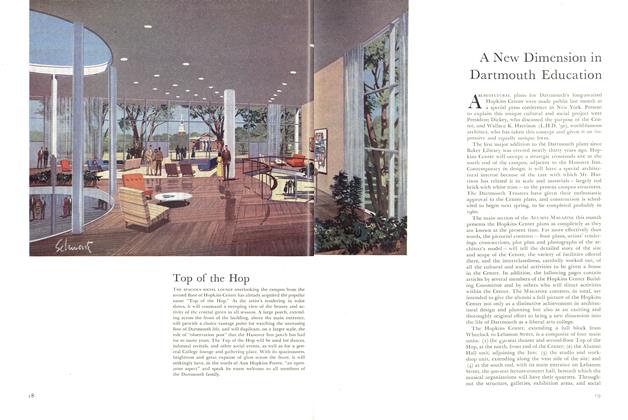

FeatureA New Dimension in Dartmouth Education

May 1957 -

Feature

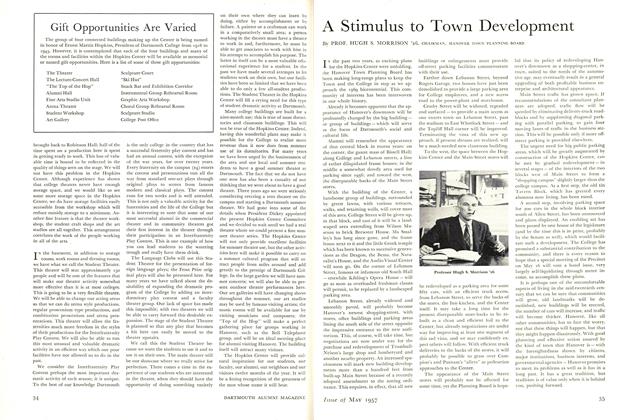

FeatureA Stimulus to Town Development

May 1957 By PROF. HUGH S. MORRISON '26, -

Feature

FeatureA Teaching Boon

May 1957 By JOHN B. STEARNS '16

ROBERT L. ALLEN '45

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Seeks Growth of Its Scholarship Funds

October 1949 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Article

ArticleThey Pull Their Weight

June 1951 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes"Reunions Are OK" Says 1945

July 1951 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Article

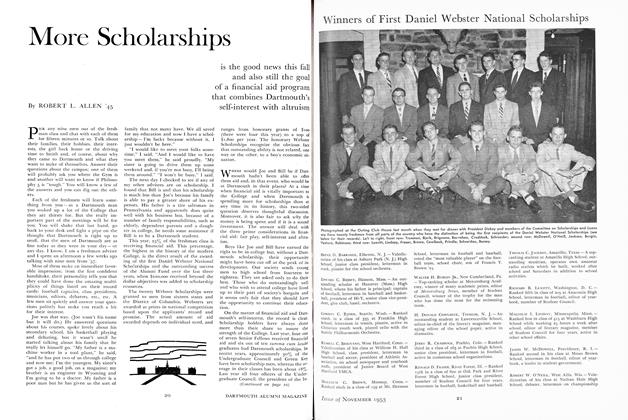

ArticleMore Scholarships

November 1953 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Feature

FeatureADMISSIONS—SCHOLARSHIPS—ENROLLMENT

April 1954 By Robert L. Allen '45 -

Feature

Feature"Dartmouth Visited"

October 1956 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45

Features

-

Feature

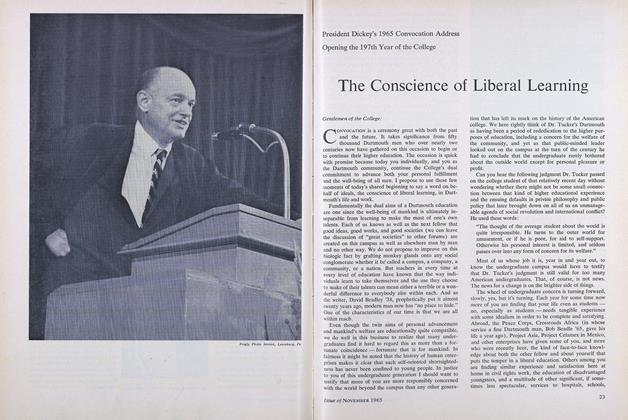

FeatureThe Conscience of Liberal Learning

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Feature

FeatureYOU CAN LIVE WHERE FOGHAT SANG

APRIL 1989 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFred McFeely Rogers 1950

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureIT'S BAD

APRIL 1989 By Edward C. Ingraham '43 -

Feature

FeatureJourney's End: The Assyrian Reliefs at Dartmouth

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Judith Lerner -

Feature

FeatureThe Second Emancipation

JULY 1963 By THE REV. JAMES H. ROBINSON, D.D. '63