ASSOCIATED PRESS CORRESPONDENT

ANTARCTICA is the Ice Age. It is a look back to the days when the great ice sheets covered much of Europe and North America. It is a look ahead to the last grim millenniums of the Earth. An Earth spinning under the waning rays of the dying sun towards a cold eternity.

Antarctica is nearly twice the size of the United States, with more ice and less life than any place on earth. Its area is nearly 6,000,000 square miles.

The International Geophysical Year studies have brought more people to the continent than ever set foot there in its entire history before. There are roughly 1500 persons in fifty camps of twelve nations. Yet the continent is so vast every person could claim an area nearly half the size of New Hampshire without treading on his neighbor's toes.

Antarctica is quite unlike the Arctic. The North and South Poles are, literally and figuratively, poles apart. The North Pole centers on a shifting mass of ice afloat on a vast ocean surrounded by land masses. The South Pole until this year was a windblown desolation of sastrugi or snow hummocks on a plateau two miles high, untouched by man since the fatal Scott expedition of 1912.

This year, for the first time in history, man has built a camp at the South Pole to face the six-months polar night. Military leader of the nine Navy men there is Lt. John Tuck '54. When I last saw Tuck he looked like young Abe Lincoln, tall and slim with a beard that reached to his chest. He is the only member of Deepfreeze I who volunteered to winter over a second year. Dr. Paul A. Siple of North Arlington, Va., Boy Scout of the first Byrd expedition of 1928, is leader of nine scientists at the Pole base.

Last summer the AP asked me if I would cover the story of Deepfreeze II, the setting up of a half-dozen American bases, including the Pole itself. The IGY year begins this July but the bases had to be built in the brief antarctic summer from November to February.

Whenever I take on an assignment I try to saturate myself with background knowledge, but here was a continent still virtually unknown. There were a lot of popu- lar tags attached to the name 'Antarctica." People immediately seem to think of "cold," "penguins," "ice," "remoteness" and so forth. After living there four months I would add the tags "dryness," "24-hour sunshine," "lifeless," "mountains" and other labels.

Antarctica is Earth's highest continent, averaging well over a mile. Temperatures at the South Pole with the sun little more than a month below the horizon have already reached 100 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. This is approximately 10 degrees below the coldest natural temperature ever recorded before. On the basis of temperature readings made in holes in the polar surface, blasted when parachutes loaded with building material failed to open last December, Dr. Siple told me he expects winter temperatures to plummet to 120 below or colder.

Tire night before I left from New York last October to fly to New Zealand I had a farewell phone call from Admiral Byrd. We had talked many times in Boston. He had been ill but was feeling better and poured his heart out. He warned me to watch for the "backslashers" who felt they had "nothing to learn from what we did before in Antarctica." Those last words came back to me time and again when I reached Antarctica. When I returned to Boston in February Byrd was . seriously ill and died before we ever talked again.

I flew to Antarctica last October 17 from Christchurch, New Zealand. It was the second earliest flight in history. The history didn't go back very far. The earliest flight was made the day before when Admiral George Dufek, Deepfreeze commander, flew across.

Never before had Antarctica been penetrated from outside so early in the season (which is of course opposite in the southern hemisphere). Surrounded by three oceans, Antarctica is belted by a ring of pack ice hundreds of miles wide that resists ships until thaws and storms in December open leads and loosen the icy chains.

The 2500-mile flight from Christchurch to the McMurdo Sound base was something less than uneventful. We took off overloaded eight tons and firing a halfdozen jato bottles to blast off the runway. The Navy R5d or Skymaster staggered into the air, overburdened with fuel in huge extra tanks set amidships. But the cold air of a New Zeland spring evening gave us enough lift to stay aloft. We dropped the empty jato bottle casings over the first open water.

A sleek P2V Neptune, the anti-submarine patrol bomber, took off with us for the flight across the stormiest ocean in the world.

Our weather briefing had been based on a handful of observations scattered through an area larger than North America. Past the point of no return the educated guess on the weather fell apart at the seams. For hours the pilots fought head winds with little hope of even ditching on the nearest edge of the continent. They fought icing when they tried to save gas by flying low- All heat was turned off to save fuel. It was below zero in the cabin where this writer, the only passenger, wondered what possessed him to say yes to this assignment.

To condense a lot of agony, the wind shifted, we sighted Cape Adare 500 miles from McMurdo and skimmed along the mountains that border the frozen Ross Sea on the west. A hundred miles from McMurdo we ran into a whiteout, a peculiar antarctic phenomenon of blinding glare that robs pilots of their horizon and has been likened to flying in milk. The faster Neptune was ahead of us trying to land. We heard the pilot talking to McMurdo, then telling the crew on the frozen air strip that he would "take over" visually. Then silence.

We couldn't find the McMurdo homer. We played tag with mountains for an hour while fuel ran out. (We learned later we were on the wrong side of 13,500-foot Mount Erebus, an active volcano, which had cut off our radio contact.) At times I could see seals turn their heads in the whiteness below. It was like white water canoeing for keeps when the mountains loomed up ahead and we banked sharply left or right. Finally the pilot gave orders to prepare for a crash landing. I was assigned to jump out with a life raft if we skidded into an open lead. "But don't pull the inflation switch until you are outside."

Just when it seemed the engines must sputter with the last drops of gas an orange streak showed below. The pilot banked until we seemed to fall through the floor. Seconds later we bumped down on the ice runway. The engines were cut and the silence after 15 hours hit us like a wall. We kicked open the frozen door but there was no reception committee on hand to hold the ladder on the slippery ice.

When the swirling storm cleared for a moment we saw why. Everybody was over at that orange patch, the tail of the Neptune, sorting out the quick and the dead. There were four of each. The whiteout had pulled the horizon out from under the pilot in the fraction of a second involved in switching his eyes from instruments to visual. The Neptune cartwheeled into the frozen surface of McMurdo Sound, 14 feet thick. Wreckage was scattered for a quarter mile.

As the only newsman in Antarctica I wrote my stories in a quonset hut chapel. The library, intended as a temporary press room, was taken over for a hospital. Months later the senior radio officer at McMurdo gave me an unequivocal statement that he had transmitted to New Zealand before our takeoff a forecast from the meteorologist that the favorable weather was breaking up.

During the next month the temperature averaged five or ten degrees below zero. The coldest was minus 35 and windy. I had quilted pants and jackets filled with synthetic fiber. Like almost everyone else I found thermos boots fine for standing around on the ice but too hot and clammy when active except in the worst weather.

THE story of McMurdo was the story of the building of the IGY station at the South Pole 800 miles away. The bottom pivot of the planet Earth centers on a flat wilderness of ice and snow. "God what an awful place" Capt. Robert Falcon Scott of Britain had written in a diary found on his body in 1912. Heartsick, their will to survive lost when they discovered Roald Amundsen of Norway had beaten them to their goal a few weeks earlier, all five died on the bitter struggle back to their base at McMurdo Sound.

From our McMurdo camp on Ross Island we could look across 200 yards of frozen bay to the hut of Scott's first expedition in 1902. Everything was perfectly preserved in the dry cold of the sterile antarctic air. Lt. Cmdr. Isaac M. Taylor, the Navy doctor at McMurdo, found tetanus germs lying dormant on the ground where Scott's Siberian ponies had been stabled a half century ago. Cases of food left in the open were still edible. Seabees used fine quality wooden matches from cartons left behind when the survivors of Scott's expedition returned to England.

I saw the first landing in history at the Pole October 31 from a plane circling overhead. A superb Navy pilot, Lt. Cmdr. Con- rad S. "Gus" Shinn of Spray, N. C., made a safe landing with Admiral Dufek on the rough polar surface. His 25-year-old DC3 is the oldest type of plane still in Navy service.

It was 58 below zero at the Pole. The sun had risen only 14 degrees in the forty days of the polar "day." At the Pole there is only one night and one day a year, each six months long. Vapor trails from our plane traced madmen's patterns in the still air of the polar plateau.

The plane's engines were kept running during the 49-minute stop on the polar surface. Not a single scientific observation was made except the temperature reading. The thermometer was part of the fixed equipment of the DC3.

A flag was planted in the surface which was so hard an ice axe had to be used to cut a hole. Most of the precious 49 minutes was devoted to talking into a recorder in front of a TV camera. Ironically, history and Madison Avenue were bereft because it later developed all the TV equipment was frozen solid. For a month afterwards I heard scientists at McMurdo bemoan the fact that no snow compaction tests had been made at the Pole nor any temperature reading below the surface. This would have given a clue to the mean annual temperature and the winter temperature, for logistic planning of the base.

My stories of the first landing were radioed to the Navy station at Balboa and by commercial wireless to the AP. But the world was coming apart and the South Pole was far away from Suez and Hungary. The Israel-Egyptian war was in the headlines. One Boston paper on its editorial page made a joke of the fact the Navy had landed at the South Pole while Europe and Suez were in turmoil. I saw Navy men who had risked their lives bite back their anger when they got that clip in the mail. We all knew that our Russian neighbors camped to the west would have paid almost any price for the scientific value and prestige of a Soviet station at the South Pole.

The United States may never give up its foothold at the South Pole. The poles are the only places on earth where man can stand with his instruments and not spin with the tired top that is his world. The drifting sea ice of the North Pole makes it unsuitable for any permanent scientific installations. At the South Pole the six-months night and use of moon cameras against the background of stars may give a precision to observations never before known. This could enable men to plot the precise distances between the continents for the first time. Errors of timing that have crept into observations made in milder climates are known to be errors of position. The continents and cities on them may be miles nearer or further apart than we realize.

A satellite fired to cross the poles must span the poles on every revolution. Fired in any other direction, except along the equator, it is unlikely to cross the same station more than a few times before it falls a flaming man-made "shooting star" in the grip of gravity. An equatorial route for a satellite is a course almost entirely over water, crossing no major country. A polar route would record data from a new slice of the earth on each revolution, yet cross the same station each circuit.

Antarctica is the greatest low pressure area in the world. In fair weather the barometer at McMurdo read 26.5 inches, below a hurricane recording in New England. A rising barometer was a sign of poor weather from the north. The weather from the South Pole was clear, dry and cold. Antarctica supports this great mass of supercooled air in a precarious equilibrium. Periodically the air mass will wobble too far, slip off the polar plateau, gain momentum in its slide down the icy slopes to the ocean and spin northward. The great anti-cyclones, a thousand miles across, whirl with their own energy and the Coriolis force of the earth's rotation, producing atmospheric shock waves felt in storms all the way to the Equator.

Observations on the earth's wobble, made at the South Pole, may lead scientists to some correlation between the maximum extent of the wobble (about 60 feet) as a trigger that sets off earthquakes. The wobble, like a tired top, may in turn be linked to great shifts in the earth's weighty overburden of air and water caused by great storms and prolonged precipitation.

THROUGHOUT November and December, while the United States re-elected Eisenhower and read of the rioting in Europe, the Navy and Air Force built a base for 18 persons at the South Pole. The Navy landed two dozen Seabees and engineers. The Air Force parachuted over 500 tons of building material, fuel and food from 80-ton Globemasters. In many cases the parachutes were worth more than their loads but the big cargo chutes were too heavy to salvage. It took 15 jato bottles, worth about $3,000 and lasting 14 seconds, to blast one plane off the polar surface. To enable the planes to take off in the thin air of the high polar plateau with a minimum of weight a refueling camp was. established below the Queen Maud mountains on the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf.

To complete their airdropping in the shortest possible time the Air Force flew Globemasters with double crews around the clock in the 24-hour sunshine. Three giant Globemasters cracked up when their nose wheels collapsed on the icy runway. The planes skidded two thousand feet but only one caught fire and that was extinguished by a Navy crash crew in action before the propellors stopped buzz sawing ice chips from the runway.

Deepfreeze II ran out of aviation gasoline in mid-December when a week more of flying would have completed the Pole supply chore. The sun reached the highest point of its months-long circuit in late December and the ice surface of the runway fell apart. The. Air Force flew its planes and men back to New Zealand, draining crashed planes and hose lines for the last drops of gasoline.

The Navy stayed in McMurdo and the men who had wintered over and claimed they had been promised relief before Christmas bitched and bitched. There were other snafus. The two Rgds, the only planes equipped for trimetrogon aerial mapping were flown back to New Zealand leaving an hour after orders were issued at 2 a.m. The aerial camera specialists were left behind to do nothing for two months.

New tractors arrived on the ships with treads 54 inches wide, useless in the hard-packed volcanic soil and ice of McMurdo. Last winter Seabee welders spent the long night cutting off the wide treads. They are probably doing the same with the new tractors right now. I asked a Navy supply officer if the new tractors for Deepfreeze III which will be loaded at Quonset next September will also have the useless wide treads. "Almost certainly" was the resigned answer.

Just before leaving Antarctica late in January I made one last ski trip beyond the New Zealand camp at Pram Point. Mount Erebus trailed a plume of steam into the blue sky and beyond Mount Terror glistened with its icy shoulders. How silent and vast a world! The Ross Ice Shelf stretched to the horizon, a triangle of ice as large as France, over a thousand feet thick, yet floating on the Ross Sea. Every few years tabular bergs bigger than the state of Connecticut break off and drift northward. It is the largest ice formation of its kind in the world.

The silence seemed to be the silence of space, the void between the planets. Scott and his men who died out there, only eleven miles from their main food cache, had written of the awesome "silence of the barrier." It was the old explorer's name for the great ice shelf.

I took off my skis and walked across some windblown volcanic ash. Almost certainly man had never walked there before. Stones fired from Erebus twenty miles away were wind-eroded by thousands of years of polar gales. In a land where no rain ever falls the lava dust was black from long exposure to the air. Your boots make white tracks in the ash. Dr. Siple before he left for the Pole had told me to search for tiny yellow lichens in the crevices of the rocks. I found several patches the size of a dime. They survived the trip back through the tropics and a Harvard professor has some of them now. He isolated algal cells which are growing in his lab.

The airplane will probably put a quick end to the mystery of Antarctica. Although less than one per cent of the continent has been explored on foot, probably half of the area has been seen from the air. The first official U.S. expedition, under Navy Commander Charles Wilkes in 1840, was partly prompted by a popular belief that the South Pole might be a vast opening into which ships could sail. Less than 65 years ago some prominent scientists did not even believe a continent of Antarctica existed at all - only a few isolated islands guarded by the great circular ice pack. Next year seismic tests will disclose whether the continent is, as some maintain, a great ice shield pinned on the edges by mountains but possibly nothing but ice to a point below sea level in the interior.

On the flight to the Pole one passes great flat-topped "horsts" of Beacon sandstone colored like autumn leaves where the wind scours the sides. On Scott's sledge near his last camp were found 35 pounds of geologic specimens including coal and other fossil proof that Antarctica was once a steaming jungle. His men had gathered them on the last desperate retreat down the Beardmore glacier.

I turned my back on the great white south for the last time. The desolation seemed to have its own cruel beauty.

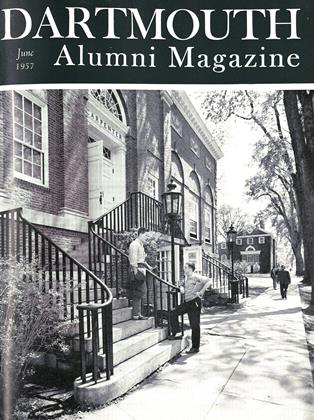

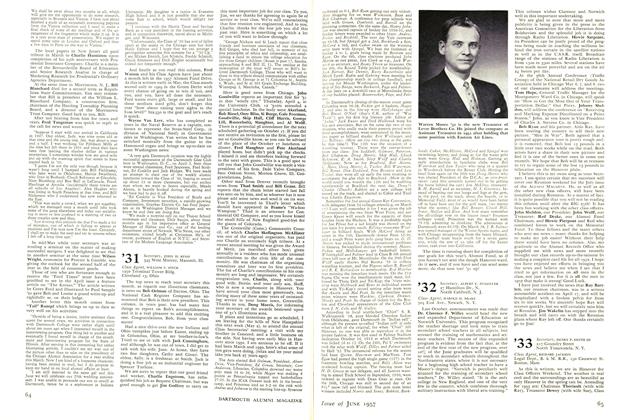

Don Guy '38 in the Antarctic interviewing Sir Edmund Hillary, leader of the New Zealandexpedition. From a camp at Pram Point, Hillary and his men will lay a string of food andfuel caches towards the South Pole for use by the Commonwealth Transantarctic Expeditionstarting late this year on the first attempt to cross the continent on the surface.

Lt. John Tuck Jr. '54, USN, holding "Bravo,"a sled dog puppy, is military leader of theUnited States IGY station at the South Pole.His unit and the scientists headed by Dr. PaulSiple are the first persons ever to winter overat the Pole itself. Tuck, son of John Tuck '05,is the first American to spend two consecu-tive winters in the Antarctic. He participatedin Operations Deepfreeze I and II.

Dr. Paul Siple, head of the U. S. scientists stationed at the South Pole, skiing amid pressure ridges in the ice near Ross Island. Mount Erebus, 13,500 feet high and an active volcano, is in the background. Pressure ridges are formed by the outward motion of the great Ross Ice Shelf past the island barrier.

The DOC flag flies at the commissioning of Little America V Station at Kainan Bay on January 4, 1956. Beneath it (l to r) are Admiral George Dufek, commander of Operation Deepfreeze; Lt. (jg) Stephen O. Wilson '55, USNR, from the "USS Glacier"; and the late Admiral Richard E. Byrd. Cmdr. Robin Hartmann '40 of Admiral Dufek's staff raised the special Dartmouth flag, now at the South Pole with Lt. John Tuck '54.

Robert L. Long Jr. '56, photographed at the Wilkes Station on the Knox Coast, where he is assisting in IGY ionosphere research for the National Bureau of Standards, and in cosmic ray research for the University of Maryland.

Comdr. Robin Hartmann '40, USN (left), onthe staff of Admiral Dufek, shown with thelate Admiral Byrd at the commissioning ofLittle America V in Antarctica last year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThirty Years After

June 1957 By RICHARD W. HUSBAND '26, -

Feature

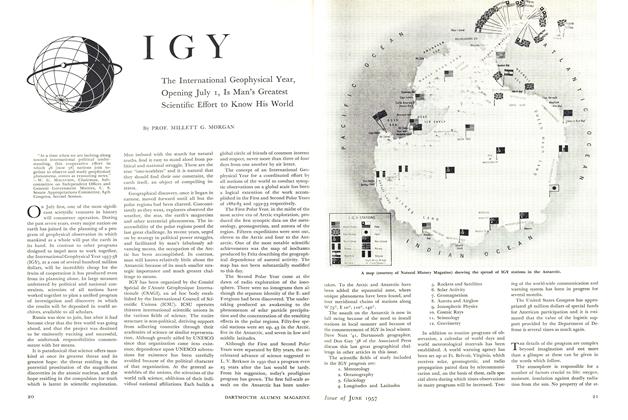

FeatureIGY

June 1957 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN -

Feature

FeatureConquest of the Antarctic

June 1957 By DAVID C. NUTT '41, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

June 1957 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, FREDERICK K. WATSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1957 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

June 1957 By JOHN H. RENO, WILLIAM F. STECK

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Library Culture

December 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJOHN RASSIAS’ EGG

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

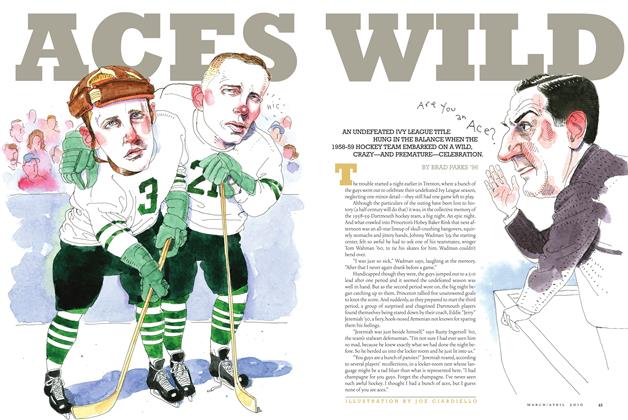

FeatureAces Wild

Mar/Apr 2010 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ten-Year Report By the Thirteenth President

June 1980 By John G. Kemeny -

Cover Story

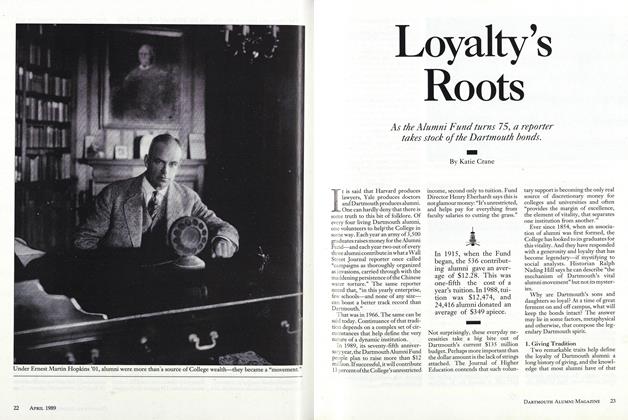

Cover StoryLoyalty's Roots

APRIL 1989 By Katie Crane -

Feature

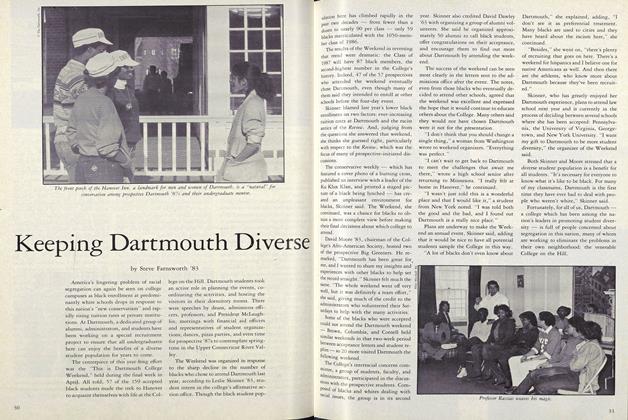

FeatureKeeping Dartmouth Diverse

JUNE 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83