A Survey of the Class of 1926 Seeking theRelation of Student Achievement to Later Success

PROFESSOR OF INDUSTRIAL PSYCHOLOGY, FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY

NONE of us needs to be convinced of the values of a Dartmouth education. We are like delegates to a WCTU convention; our opinions are already formed. But when pressed for a concrete explanation or analysis of the benefits of higher education, Dartmouth or elsewhere, we become woefully vague.

As an Industrial Psychologist, who has helped train students to take their places in business and has hired the products of colleges, I was interested to discover if it might be possible to predict from a man's record of achievement in college how well he might fare two or three decades hence. Answers to this question will shed light on the general values of higher education, how important various phases of it may be, and will also help guide college recruiters who come in increasing numbers to campuses to interview seniors.

These recruiters may or may not have preconceptions whether to view with favor high grades, athletics, fraternity membership, literary or musical activities, or campus politics - or any combination of these. In any case, whatever opinions they have are hunches, and little more. They are not based on any body of facts.

So my idea was to take my own class of 1926, thirty years out, and try to correlate their 1956 status with curricular and extracurricular records while in college. It is not unique to survey a college class; there are many 25th (or other) reunion annuals at Dartmouth and other Ivy League colleges. However, they are generally chatty, dealing with wife and children, beer and poker, church and politics, sometimes with a tabulation of vocations and perhaps incomes. But almost none has gone beyond such description and attempted to isolate causative factors.

A four-page questionnaire was developed after a great deal of study, consultation with classmates, professional associates, and industrial personnel men. In addition to a printed letter of explanation of the purposes, the topics covered were: education after Dartmouth; occupation, title, and salary; side earnings and investments; successive jobs held since college; outside professional, civic, or hobby activities; and satisfaction with college major and a liberal arts education. (Findings from several of these factors will not be discussed, because the data disclosed nothing of significance.) Confidentiality and anonymity were promised.

These questionnaires were mailed in June 1956 (thirty years to the week since graduation) to every graduate and nongraduate ever affiliated with 1926, a total of nearly 500. With the aid of three follow-up reminders, finally 275 of 368 graduates replied. This 75% of replies is fairly satisfactory, as it suggests a representative cross-section. Most reunion annuals, Dartmouth and elsewhere, have shown about two-thirds response. Thirty-four non-grads, 28%, returned their forms, but we would expect in general a lesser degree of interest.

The information obtained fell into four main categories: I. COLLEGE: 1. Academic, 2. Extracurricular; II. THIRTY YEARSLATER: 1. Vocational, 2. Avocational.

College data were gathered from records at Hanover and from the 1926 Aegis. Let me express publicly my appreciation for the enthusiastic cooperation of Bob Conant and Don Cameron and their staffs. I might also remark that the data were in such fine order that instead of the full month I had expected the work would take, last August became one-third work, two-thirds vacation!

A COMPOSITE PICTURE 30 YEARS AFTER

This part is not unique, as it has been done with other Dartmouth classes, and in other colleges, so this part of our treatment shall be brief and used only to lay a foundation for the cross-tabulation.

It was a surprise to see the number of classmates who undertook further formal education after leaving Hanover. 196 (71%) have taken one or more formal courses. 127 (35%) earned an advanced degree. 22% took one or more courses to better themselves vocationally, mostly in business or finance, salesmanship, industrial relations, and speech. 6% more mentioned courses for culture, enjoyment, or personal improvement.

Of the advanced degrees, the totals are: 26 Law, 24 Master's in Business Administration, 20 M.D., 14 Ph.D., 16 Master's (but not Ph.D.), 11 Master's in Education, 11 Engineering, Mining or Architecture, 5 Religion or Literature. So the stereotype of ivy-clad halls direct to Wall Street seems far from the typical case, even though we do have our share of inhabitants of the canyons of Lower Manhattan.

The occupations '26 has entered follow. Classification is in terms of actual duties, as reported by the man himself. Thus, if he is an attorney for an insurance company, he is listed as law rather than insurance. The occupations: 49 store owners or managers, including restaurants; 38 sales managers or salesmen, including insurance; 30 top executives; 21 lawyers; 19 doctors (1 dentist; no psychiatrist); 16 bankers; 16 educational administration, college or secondary; 15 engineering, architecture, efficiency experts; 15 teachers, 12 college, 3 secondary; 14 public relations or promotional; 10 scholarly, not college, such as industrial chemist; 9 advertising; 7 esthetic: music, photography, theater, ministry; 2 owners of manufacturing establishments; 7 unclassifiable or retired.

The range of incomes reported was from $3,000 to over $300,000, with a median of $14,950. 85 men (31%) earn over $20,000. How high many of them go, I don't know, as in my ivory-tower ignorance of such lush figures my highest bracket to be checked read simply "Over $30,000." I wish now I had included at least one higher category. The distribution of earnings was:

7 Under $5,000

32 Between $5,000 and 7,499

26 Between $7,500 and 9,999

47 Between $10,000 and 12,499

26 Between &12,500 and 14,999

49 Between $15,000 and 19,999

85 Over $20,000

Do we punch the time clock, or work for ourselves? 97 men, 36%, list themselves as self-employed. It seems to pay to work for oneself, as the 39 professional men on their own hook have a median income of $19,445, while the 58 men in business for them- selves average $19,417. Both figures are nearly five thousand above the class median.

Data as to activities outside of work actually added little to the practical part of the study, so let us merely observe that our alumni have been very active in professional organizations, civic and community affairs, but have been far less inclined to affiliate with such clubs as Rotary, Kiwanis, Elks, etc. We have vigorous interests outside the home, but are by no means "joiners."

Three-fourths said they would elect the same major if they were to go through college again. Of the 70 who would choose a different one, 22 would elect one in liberal arts and the other 48 would take a more practical one - usually business. A number commented spontaneously that apart from the major, more emphasis should be devoted to written and spoken English.

Only 21 (7%) would choose another college in their reincarnation. Whether this is well-thought-out conviction or pure loyalty, one can only guess. Of these few, 7 would choose engineering, and the other 14 some highly practical course, usually business. There were quite a few com- ments to the effect that a liberal arts education is preferable, but that a somewhat greater proportion could be profitably devoted to practical subject matter.

COMPARISONS AMONG ACTIVITIES AND ACHIEVEMENTS

IBM tabulating being so rapid and flexible, we were able to indulge in virtually unlimited cross-analyses. Many of these comparisons involve present income, as correlated with undergraduate data. This brings up the most baffling, and perhaps insoluble, problem of this entire investigation. JUST WHAT IS LIFE'S SUCCESS? I have discussed this at length with classmates, educators, and business men. The three factors that constantly crop uppermost are: (1) Income; (2) Title, such as senior partner, sales manager, or bishop; and (3) Satisfaction. It is hard to avoid the financial as the prime index. Title is far from satisfactory; for example, the owner of a general store may be less of a merchandiser than say a buyer for a single department in a big city store. Satisfaction with life's success is a fine thought, but it is hard to judge, and frankly sometimes hard to separate from weak ambition or even downright laziness.

Finally, I decided to use two indices of success, and treat the data two ways. (1) Income. (2) An index based on how well a man has done in his profession in comparison with estimated opportunities. Where earnings reflect skill and effort, as in selling or private law practice, it is not too difficult. But where salaries are involved, as in a banker or teacher, the size of city and type of organization complicate evaluations.

Undergraduate Grades and Income. The first thing the typical recruiter inspects is the senior's academic record. This table shows the relation between college grades and income thirty years later:

Point Average Number Median Income 1.50—1.69 17 $10,625 1.70-1.89 49 14,250 1.90 - 2.09 36 15.625 2.10 - 2.29 31 14,375 2.30 - 2.49 50 14,680 2.50-2.69 19 14.375 2.70 - 2.89 24 15,000 2.90-3.09 17 13.125 3.10 - 3.29 11 16,250 3.30 - 4.00 14 20,000 plus

Trends appear only at the two extremes. First, we see that those who barely graduated have definitely lower earnings. Whether this might be because they are not quite so talented as the majority, or whether there was lower motivation both in college and subsequently, is a matter of speculation. Second, contrary to the stereotype that "The Phi Bete is a low-salaried intellectual," we see the top two groups showing a definite rise in income. The truth is that of the 22 awarded Phi Beta Kappa, 13 are earning over $20,000. Only five entered scholarly work, four as college teachers and one in research. Six became lawyers; virtually all the rest are in some form of business.

Without taking space to present detailed figures, comparisons between intelligence test scores and present earnings permit three conclusions: (1) Those lowest in the scale have not done so well; this agrees with the statistics involving grades. (2) The very highest fall off in earnings. This was supposed to occur with grades, but analysis discloses that in our class the men going into scholastic work were more likely to be B students with exceptionally high intelligence scores. (3) Between these extremes, no special trends appear.

Major and income show about what one might expect. Those choosing Tuck School or Economics have achieved the highest median return: $16,800. Social science was second highest, but many of our business men specialized within that area. Third was basic science, chiefly taken by pre-medics. Cultural majors have present income nearly fifteen hundred dollars below class median. Perhaps these facts reflect personal scales of values as much as they do the preparation for vocation provided by the various specialties.

Extracurricular Activities and Income. We all know that the role of outside activities in college life has been questioned. Not only does the recruiter lack evidence, but some college administrations begrudgingly tolerate rather than encourage these activities outside the classroom. This table shows a direct relationship between the extent of extracurricular participation and present earnings. The same is true with regard to numbers of activities - those who engaged in three or more now earn a median of $18,750 yearly.

No participation 78 $13,840 Slight participation 126 14,220 Wide participation 46 15,625 Outstanding success 16 20,000 plus

Fraternity membership was not counted as an activity in the treatment above, but was surveyed as a possible additional factor, and produced one of the most surprising findings in this entire investigation. We see a difference of $4,000 in favor of fraternity members: Fraternity Members - $15,235, Non-Fraternity - $11,250. One might be skeptical as to this much benefit from whatever social or personality development accrues from such membership. More likely is the social personality already formed by eighteen which persists throughout adult life. The theory that they came from more well-to-do families and were more likely to fall into plush jobs is discounted by knowledge that relatively few of our class did have such hereditary sinecures.

Sports. Movies and fiction are full of stories of the All-American who turns out to be a complete bum. How about this? As these figures show, our athletes have done all right for themselves after thirty years in the world.

No athletics 194 $14,280 1926 numerals only 18 15,000 "D" letter 24 18,575 Two letters 9 17,500

Literary and musical leaders have done well in subsequent years. Those who became editors or top staff members, leaders, or engaged in several literary or musical pursuits now average $16,250, as compared with the class median of slightly under $15,000. Those who were "privates" in these organizations average a few hundred above the entire class.

"Political" activities, grouping class officers, Green Key, Palaeopitus, and senior societies, show even more pronounced trends. Again, this is especially true for those who held two or more such positions or memberships.

None 185 $14,250 One 43 14.583 Two or more 38 20,000 plus

One might conclude that the same traits that made them selected by their own classmates also have led them to be chosen by boards of directors, or in the case of professional men made them unusually successful in their vocations.

All in all, there is no doubt that we have proven a case in favor of extracurricular participation. Like many such correlations, however, we have not necessarily demonstrated that participation developed the traits which created vocational success. Possibly the ultimate answer is that effective work habits, broad interests and enthusiasms, and desire to succeed, are what bred success at two stages of life.

Actually, we have found higher correlations between extracurricular records and life's success than between academic data and income. I think we could agree with the recruiter who looks at both the classroom side and the activity side in sizing up a senior applicant. On the basis of our data, if we were to choose a recruit for top executive training, we would look for a senior with one or more of these attributes: breadth and success in several outside activities, a class political leader, and/or better than a B average.

Next we attempted to balance classroom and outside activity records to derive an all-round rating of college achievement, and we obtained these figures: College scholarship poor and little or no extracurricular - $16,667; Fair in either or both combined - $13,889; Average in combined rating - $14,422; Top quarter in both, or outstanding in one and above average in other - $19,603.

This gives substantiation to the recruiter who says he would like to employ the B student with some outside activities. The peculiar status of the "poor" group is puzzling; but the number of cases was limited, and also virtually every last one in this category went into a financially profitable occupation.

College Record and Life's Record. Let us now compare the two ratings: judgment of a man's college career and rating of his general progress since. I'll admit that dividing people into four or five categories is open to error, and that more intimate acquaintance with each person might cause some changes. The table does demonstrate general correspondences, but as usual in the case of data in social areas trends rather than absolutes appear.

Thus we see that of the seven who were judged to have made poor vocational progress only one had even an average undergraduate record. The rest barely graduated and had little outside activity. One step higher was the list of those who have made only mediocre success in life, and 70% of these had mediocre college records also.

At the other end of the scale we observe what has commonly been found — it is easier to predict mediocrity than success. This is probably because any one crucial failing can produce mediocrity, while all factors have to be favorable for success to occur. We see that of the 32 now rated as outstanding, only six had college ratings of poor or just fair, while half of this group, 16 of the 32, had highly superior school records as well as having made an exceptional mark in the world. So we do find correspondence, but as a trend rather as an inclusive and exclusive certainty.

We previously pointed out that D winners earn about §3,500 more than class average. Using this alternative criterion of success, they still appear to advantage. Whereas just 9% of die class won a varsity award, 25% of those now rated as outstanding made a team. Again, 1926's sports leaders were not bums and have not become bums. Of the 24 letter winners, three are rated as having a poor or mediocre career, 13 as good, and eight as outstanding.

SPECIAL GROUP

In addition to studying the class as a whole, certain special groups should be surveyed, specifically: (1) Those who did not do so well in college, but who have made fine successes since; (2) Today's status of undergraduate leaders, and the reverse - the undergraduate performance of today's men of outstanding accomplishment; (3) Those in Who's Who; and (4) The non-graduate.

1. Mediocre in college - excellent vocational success. Just as we have stories of the big wheel in college who becomes a bum, so we also have fiction about the nonentity who returns to reunion in a Rolls Royce and gives a million dollars to the alumni fund. For the business world this man presents a challenge. If we reject him while on a recruiting trip, because he has barely passed his courses and has done little in extracurricular lines, we may be overlooking a potential major executive two or three decades hence. Is there any way by which such a person might be identified while still in college?

There were 50 cases of men whose grades point average was below 1.90 and who engaged in little or no outside activities, and yet who at middle age report earnings better than $15.000. Their grades were of course low, so this factor needs no discussion. Their median rank on the aptitude test was only a trifle higher than their classroom rank, so the special success of this group was not due to any hidden intellectual talents not being used on the books. We must look to personality factors, then. Since their extracurricular participation was by definition scanty, a recruiter couldn't look for factors outside the classroom. A few more did major in a practical area, but the proportions were not significantly different. Exactly half of this group is composed of executives, salesmen, sales managers, and financiers.

Now, here is an interesting figure. Two-thirds of them took further education after Dartmouth, in spite of their undergraduate performance suggesting a disinterest in book learning. Almost a third earned some advanced degree. Actually, analyzing individual cases, much of this reversal is contributed by the MD's, the majority of whom had surprisingly poor undergraduate records. They averaged 2.05, scarcely above a straight C.

These facts suggest a possible explanation. The president of another New England college has dubbed these people "late bloomers." Perhaps there is no way of predicting by springtime of their senio-year that some people will ultimately become real successes. So we seem forced to the conclusion that both they as job aspirants and the recruiters seeking developmental material would be disappointed. However, let us point out that these cases of drastic change are exceptions rather than the rule; the rule is agreement rather than reversal of form.

2. "Men of Distinction." Fifteen men who have been prominent in class affairs and have wide acquaintance were asked to suggest two lists of ten or a dozen each of (1) men who were outstanding as undergraduates, and (2) men who are highly successful today. While 42 and 63 nominees were suggested, it was surprising to see how a few names repeated on list after list. Actually, 15 men received five or more votes for college status, and 15 also were nominated five or more times for outstanding success since graduation. Six names were on both lists.

The undergraduate leaders could be described thusly: Only slightly above average in scholarship and intelligence score. Every one was prominent in extracurricular activities, 10 of the 15 having highly successful records and the other five having a good amount of participation. All 15 belonged to fraternities, and 11 won athletic awards: one numerals, six "D". and four others two letters. Checking their record after college, 11 of the 15 now earn over $20,000, and all 15 are above class average. Eight received an advanced decree, and three more took isolated courses. Vocationally they show quite a range, with three in the investment area; two each are listed as top executives, sales executives, public relations or promotional work, and medicine; and one each in law, advertising, banking, and foods. 40% of this group has held five or more jobs, as compared with 20% of the class having moved that often.

Those '26ers who were nominated as being outstandingly successful at our present age averaged in the top fifth of college scholarship, and Bof the 15 won Phi Beta Kappa or other scholastic honors. They were not quite as outstanding in undergraduate affairs as those judged class leaders in those days, with just four rated as outstanding and another four as having engaged in a rather wide range of activities; therefore seven took part in little or none, as compared to no one in the undergraduate distinguished group. Seven had earned one or more D's, one his numerals, and seven engaged in no sports. Whereas all 15 of the undergraduate leaders belonged to one or more honorary societies or were class officers, just eight of those highly successful in later days were recipients of such college honors. Two-thirds took further education, five for degrees and five more electing isolated courses. Twelve of 15 now earn over $20,000, but it is interesting - and in a way gratifying - to see two people in the $10,000 bracket nominated as being outstandingly successful in their own fields of endeavor. Like the undergraduate leaders, 40% of these present-day leaders have held five or more jobs, demonstrating again that switching jobs can lead to great improvement.

We might summarize by saying that without exception our undergraduate leaders have made either superior or excellent records in the world, and as a whole our middle-aged standouts had fine college records 30 years previously - scholastically, extracurricularly, and socially. There are four of the latter group, however, who were judged to have had mediocre or even poor college achievement. These perhaps are the "late bloomers" discussed above.

3. Who's Who. To the best of my knowledge, 15 men of 1926 have been given this well-known recognition. I'll challenge any other class, Dartmouth or elsewhere, to show better than one graduate in 15 getting into Who's Who.

Who's Who is tied up rather heavily with scholastic and literary endeavor, and we find that 9 of the 15 could be so classed: 6 college teachers, an educational administrator, a museum director, and a biological researcher. Two others are lawyers, and four are in business. All but one engaged in further education after graduation, and 11 earned higher degrees.

The undergraduate records of this Who's Who group were exceptional. The grade point average was 3.30 (better than B); 8 made Phi Beta Kappa, and three others lesser scholastic honors. As a whole, this group also went in strongly for extracurricular activities; 11 of the 15 engaged in three or more activities. Nine were on athletic squads, five winning a total of six D's. Eight had records as class officers or such organizations as Green Key, Palaeopitus, or a senior society.

Present earnings of Who's Who men present a strange picture, with no one near the class average. Seven earn over $20,000; the other eight in the neighborhood of 8-10 thousand. This is the academic influence!

4. Non-Graduates. The original questionnaire was mailed to all connected with 1926, graduate or non-graduate. In follow-up reminders, not as much effort was made to elicit replies from non-grads. For one thing, many are not so interested in the College, and the ratio of returns would be bound to be small. Also from a statistical standpoint data are incomplete and hard to treat properly, because some didn't even finish the first semester and others put in four years but failed to receive a diploma due to low grades or over-cuts. Extracurricular data ' were not available, since their names did not appear in the Aegis.

However, for what the data might be worth, let's see what happened to the 34 non-grads who did reply. About a quarter had been separated, and the majority were behind an average necessary to graduate. But one earned a Ph.D., a second a Phi Beta Kappa key elsewhere, and four more bachelors' degrees. One is an MD, and four have law degrees.

Median earnings of this group are 516,875. Vocations are very diverse, with appreciable groups only for executives and financial or investment areas. One doubts whether such a small sample is typical. The self-selection factor might be crucial; in fact the high median income suggests the possibility that those who replied may be mainly those who have done well and are proud to show that they have succeeded without being handed a sheepskin.

Vocational RecordCollege Record Poor Mediocre Good Outstanding Total Poor 1 8 18 1 28 Fair 5 75 5 98 Average 1 7 85 10 103 Top quarter combined 2 27 14 43 Outstanding in both 2 2 Total 7 30 205 32 274

This '26 group on the Alpha Delt porch senior year includes Hal Gibson (seated) and (l to r) Bob Loomis, Obbie Barker, the late Heinie Sage, Red Merrill and George Tully.

BEFORE GOING to Florida State University in 1953, Professor Husband taught psychology at the University of Wisconsin and lowa State College and for three years in between, 1942-45, did industrial relations work for the U. S. Steel Corporation. Among his books are Applied Psychology (1934, 1949), General Psy-chology (1940) and The Psychology of Success-ful Selling (1953). A native of Hanover, he is the son of the late Prof. Richard Wellington Husband, who taught Greek and Latin at Dartmouth from 1900 to 1919, was Associate Dean from 1919 to 1923, and was Director of Personnel Research at the time of his death in 1924.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAssignment: Antarctica

June 1957 By DON GUY '38, -

Feature

FeatureIGY

June 1957 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN -

Feature

FeatureConquest of the Antarctic

June 1957 By DAVID C. NUTT '41, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

June 1957 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, FREDERICK K. WATSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1957 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

June 1957 By JOHN H. RENO, WILLIAM F. STECK

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Official Dartmouth Reunion Guide to Greenspeak

MAY • 1987 -

Feature

FeatureHEAR ON THE STREET

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

MAY | JUNE -

Feature

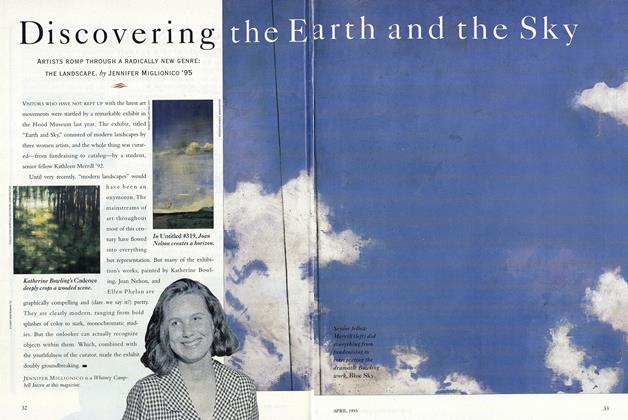

FeatureDiscovering the Earth and the Sky

April 1993 By Jennifer Miglionico '95 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryLouis Burkot

OCTOBER 1997 By Jon Douglas '92 -

Feature

FeatureWomen at the Top (almost)

May 1977 By SHELBY GRANTHAM