A New Translation. By FrancisSteegmuller '27. New York: Random House,1951- $3.95.

While unlikely to prove the definitive translation of Flaubert's novel, Francis Steegmuller's centennial English version is notable for its intelligent and highly skilled fidelity to the letter and spirit of MadameBovary. The translator was well prepared for his exceedingly difficult task by long familiarity with the great novelist, by painstaking study of many thorny textual problems, and by his uncommon acquaintance with the resources of both the French and the English tongues.

In an absolute sense a perfect translation of such a book is an unattainable ideal. But judged against what might be considered humanly possible, this rendering must rank high, in spite of certain weaknesses. While it is almost completely free from glaring misunderstandings, it does contain a number of examples of erroneous or inadequate translation, some gratuitous additions and occasional paraphrases which are a kind of surrender to the undoubted difficulty of the problems set by certain passages.

"Troubles du coeur" means "turmoils of the heart," rather than "broken hearts" (p. 41). The "bosquets" of the nightingales are not "thickets" (p. 41) but "groves." When Emma passionately tells her lover Rodolphe he is "beau" and "intelligent," the English equivalents are "handsome" and "intelligent," not "beautiful" and "wise" (p. 215).

The whole imagery is changed and weakened when "unlimited opportunities for deep emotions and exciting sensations" (p. 50) is used to render "des existences ou le coeur se dilate, où les sens s'épanouissent." There is a similar weakening and de-poetizing in the translation, "Since he had heard the same words uttered by loose women or prostitutes" (p. 215) for "Parce que des l&vres libertines ou vénales lui avaient murmure des phrases pareilles."

Possibly less excusable is the addition of words to make explicit what was implicit in Flaubert's text. Such additions are italicized in the following examples: "Human speech is like a cracked kettle on which we tap crude rhythms for bears to dance to, while we long to make music that will melt the stars" (p. 216) for "La parole humaine est comme un chaudron fele où nous battons des mélodies a faire danser les ours, quand on voudrait attendrir les étoiles." "She loosened thesilk ribbon of her hat" (p. 292) for "Elle denouait son chapeau." Or "a romantic pile of ruins" (p. 391) for "un amas de ruines."

But the number of such weaknesses is relatively small in the whole closely textured novel. Mr. Steegmuller has unquestionably done a great service to English readers of one of the world's great novels.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

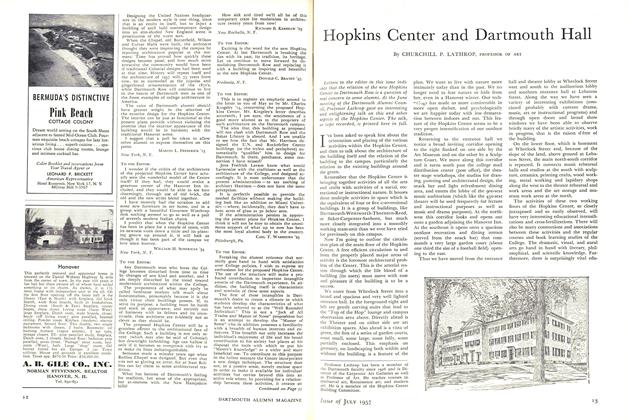

FeatureHopkins Center and Dartmouth Hall

July 1957 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Feature

FeatureThe Commencement Address

July 1957 By DOUGLAS HORTON, D.D. '57 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1957 By JAMES M. O'NEILL '07 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1957 By LLOYD L. WEINREB '57 -

Feature

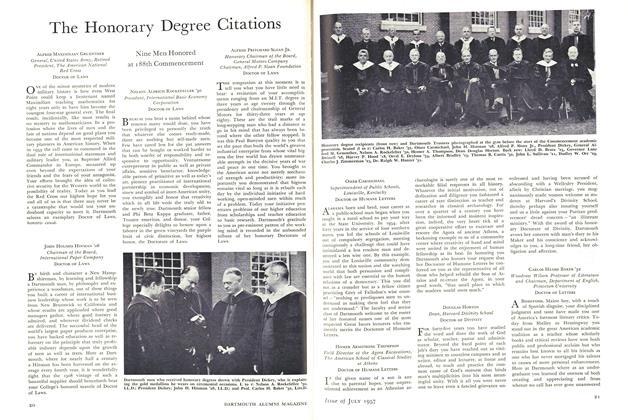

FeatureThe Honorary Degree Citations

July 1957 -

Feature

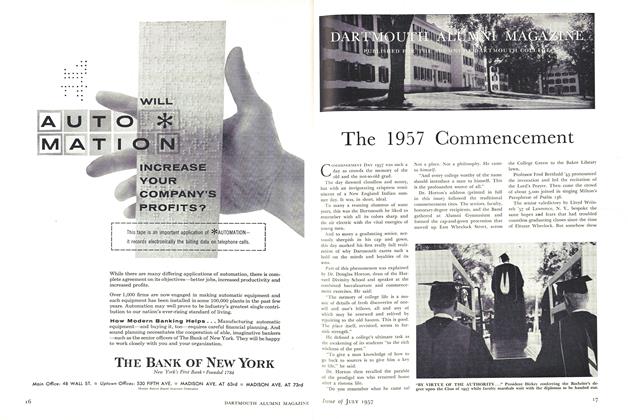

FeatureThe 1957 Commencement

July 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

GEORGE E. DILLER

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

July 1920 -

Books

BooksJohn C. Holme '30

MAY 1930 -

Books

BooksThe Arts Anthology, a Book of Poetry

MAY 1930 -

Books

BooksTHE PATTERNS OF ENGLISH AND AMERICAN FICTION

February 1943 By Allan Macdonald. -

Books

BooksAMERICAN FEMINISTS.

NOVEMBER 1963 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Books

Books"Psychology and the Days Work"

February 1919 By CHARLES FREDERICK ECHTERBECKER