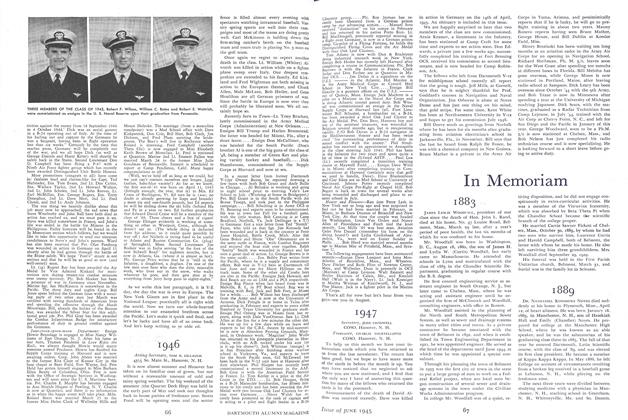

Autobiography of Professor John Moffatt Mecklin Should Hold Special Interest for Dartmouth Readers

by John M.Mecklin. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York,'945, 293 PP- $2.75.

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF Professor Emeritus John Moffatt Mecklin, which is quite possibly his finest book and certainly will be his most popular, has appropriately appeared with the title My Quest For Freedom. This book, especially important for Dartmouth men, should appeal to all interested in college education and also to those interested in the ever-continuing fight for freedom. In this fight Professor Mecklin has been a fine soldier all his life. We owe him a lot and I'm sure that his students more than all others realize this. I mean his students not only at Dartmouth but also at Lafayette College and the University of Pittsburgh.

My Quest For Freedom adds new dignity to the profession of teaching. It indicates that teaching may well be a hazardous profession demanding not only intelligence but courage as well. When a man deals with ideas, "fictions" or symbols, he is dealing with dynamite. The fact that Professor Mecklin survived to a mellow old age and retired with honor is a tribute to his good judgment, to his never failing sense of humor, and to the fact that he never hauled down his flag and surrendered to academic and administrative reaction.

More than half of his book deals with his escape from that theological nightmare known as Calvinism. Born in the hinterland of Mississippi (Choctaw County), son of a strict Presbyterian minister, his boyhood and youth, even extending far into maturity, "were far from being sane and rational." The dogma of eternal damnation, the utter corruption of human nature, the emphasis on sin, and the doctrine of the "elect" made him utterly unhappy. So much so that after vegetating mentally and spiritually in a small Presbyterian college he suffered a nervous breakdown. He lived, as he said, in a tragically unreal world.

After spending a dismal time in the doltish Ph.D. mills in Germany he found spiritual liberation in Italy and Greece, and by 1905 when he took a newly created chair at Lafayette he could truthfully say, "From this point on the last word in my philosophy of life became and still remains homo sumhumani nihil a me alienum puto." (I am a man and deem nothing human alien to myself.)

Because Professor Mecklin advocated free discussion of religious questions, as well as of some of the more subtle points of theology and dogma, and encouraged his students to think for themselves, he soon came into conflict with President Warfield of Lafayette, who was determined to force the teaching in Lafayette to conform to the orthodox theology of Princeton Seminary, where he was President of the Board of Trustees. To make a long story short, after eight years of brilliant and stimulating teaching Professor Mecklin was forced to resign. He fared little better at the University of Pittsburgh where he clashed with the capitalistic steel interests.

When he came to Dartmouth he found the heritage of freedom left by President Tucker to be our most precious possession. President Hopkins, who thinks Professor Mecklin's estimate of Dr. Tucker's influence the best in print, carried on this tradition, and under him Dr. Mecklin found complete intellectual freedom and happiness.

Professor Mecklin found impressive, and the reader will too, President Tucker's faith in Dartmouth as written in a letter to the Boston Alumni Association in 1919, when he was in his eightieth year: "The faith, that is, of the open, the courageous, the undistorted, the unconfused mind in the presence of great issues as they arise. This is the power as X apprehend, perhaps the greatest gift of our inheritance as it is the greatest discipline of our citizenship, through which we as the sons of Dartmouth, and as loyal citizens of the state are to strive to fulfill the 'unmanifest destiny' whether of the college or the nation."

With the passing o£ the years Professor Mecklin became an enthusiastic fisherman, and all anglers and nature lovers will enjoy his chapter on fishing in the Connecticut, and other waters. This is one of the finest chapters of the book.

My Quest For Freedom is a most interesting autobiography, but it is also an illuminating commentary on the United States written by a kindly and civilized man.

Professor Mecklin is one of Dartmouth's great teachers and his book is at times a noble record of a career full of richness and variety far beyond the lot of most college teachers.

I hope it reaches the wide audience it deserves.

JOHN MOFFATT MECKLIN, Professor of Sociology, Emeritus, whose autobiography, "My Quest for Freedom," tells much of his happy teaching ex- periences at Dartmouth,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

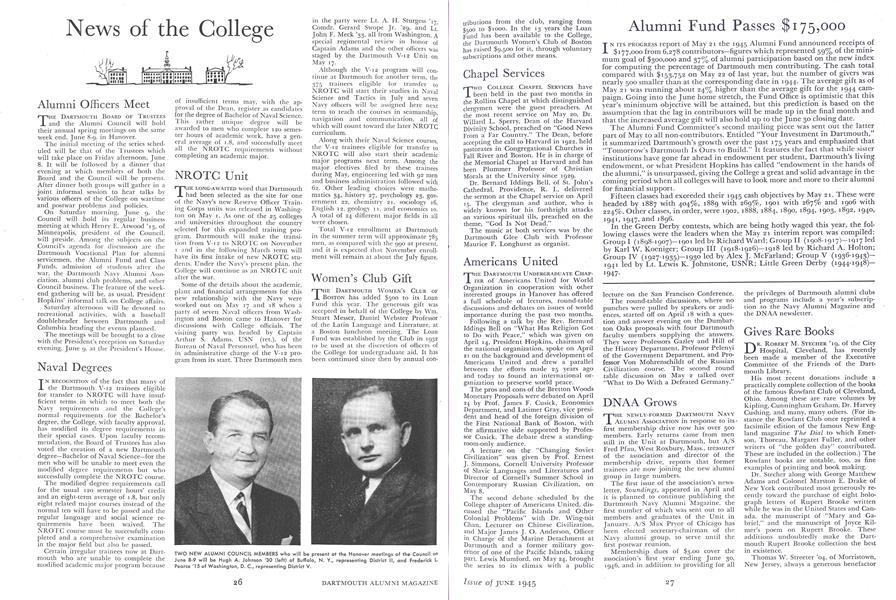

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S RIVER

June 1945 By Alice Pollard -

Article

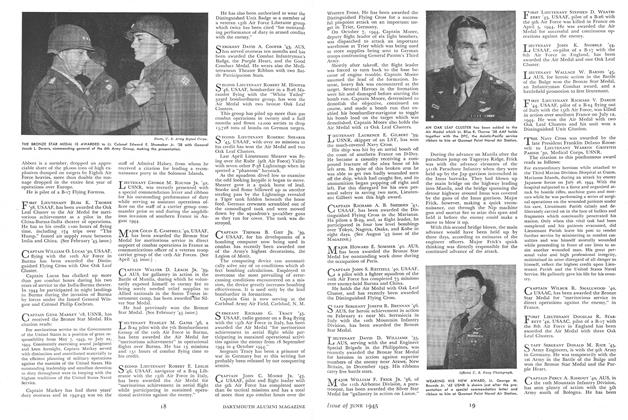

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

June 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleFOR MILITARY TRAINING

June 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

June 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1908

June 1945 By LAURENCE SYMMES, WILLIAM D KNIGHT, ARTHUR BARNES

Herbert F. West '22

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1935 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1944 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

December 1946 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksNO PLACE TO HIDE

January 1949 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1950 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

March 1956 -

Books

BooksNATURAL PHILOSOPHY AT DARTMOUTH: FROM SURVEYORS' CHAINS TO THE PRESSURE OF LIGHT.

November 1974 By ALLEN LEWIS KING -

Books

BooksReadings in Money and Banking

January 1917 By EDMUND E. DAY. -

Books

BooksSTEEPLE BUSH

July 1947 By Francis Lane Childs '06 -

Books

BooksMOUNTAIN CLIMBING GUIDE TO THE GRAND TETONS,

November 1947 By Henry Coulter '43, NATHANIEL L. GOODRICH -

Books

BooksTHE ELECTRIC INTERURBAN RAILWAYS IN AMERICA.

June 1960 By WAYNE G. BROEHL JR.