'41, PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

EVER since Vice President Nixon's adventuresome journey through eight of the ten republics in South America last spring there has been an increased interest in the regions to the south of us which most North Americans vaguely lump together as "Latin America." Most appear to be puzzled by Mr. Nixon's reception, and ask with some asperity, "What happened to the Good Neighbor Policy?" Much of this bewilderment stems from the profound ignorance of the area on the part of most Americans. One is reminded of the story told about Queen Victoria who upon hearing of the illtreatment of the British minister to Bolivia called for a map of South America, crossed out Bolivia with a flourish, and said, "For us Bolivia does not exist!" For most Americans Latin America simply does not exist except on the occasions when revolutions or attacks on the Vice President cause the region to leap into the headlines.

Latin America is important to us. Politically they share our Western European heritage, and, however imperfectly, strive toward the ideal of representative democracy. Every nation, with two rather shortlived exceptions, at the time of independence adopted the republican form of government. Currently in the United Nations the so-called Latin American bloc usually is found in support of the United States point of view, although one must admit that this support is not now as readily forthcoming as previously. Economically Latin America is of immense importance to us. There we find in abundance such strategically vital commodities as oil, tin, copper, lead, and zinc, and agricultural products such as coffee and bananas. The population of Latin America is growing by leaps and bounds. It is, in fact, the fastest growing population of any of the world's areas. Politically, economically, and strategically Latin America will be an area of growing importance to us in the future.

Today Latin America is a land of unrest, but it would be in error to say, as most writers have been saying since Mr. Nixon's trip, that this unrest has bubbled up during the past few years. The difficulties in Latin America have deep roots in history, and although the people there have as much right to call themselves "American" as we do, it would be foolish not to recognize the great differences between the Anglo-American and Hispanic-American heritages. The very word "Latin America" is somewhat of a misnomer. Latin America is by no means a cultural unit. The peoples range from the most primitive Indian of the Amazon region and the hardly less primitive Indian of the highlands of Guatemala, Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador to the very sophisticated upper-classes of Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, and Mexico City. They live in twenty republics, eighteen speaking Spanish, one French, and one Portuguese. Each nation has its own deep pride in its individual history. They have been molded by forces whose similarity to those at work in Anglo-America is more apparent than real.

Take, for instance, the Indian. The history of both areas in North America is replete with heroic exploits involving the conquest of the Indian, but the final result and, what is perhaps more important, the attitude taken towards these conquests are quite different. We erect statues to our colonial forefathers who trod the redman beneath his foot, and blazed a bloody trail of white supremacy from Atlantic to Pacific. Contrast this with the attitude in Mexico towards the conquistadores of Cortez. Cortez, the Mexican child is taught, struck down the great Aztec nation, and forced the Mexican into a 300-year period of enslavement to Spain until independence was restored by the Mexican insurgents during the war for independence. As Latin Americans often put it, "You North Americans killed your Indians; we married ours!" Although practically all these liaisons were without benefit of clergy, there was produced a great new race, the mestizo, part white and part Indian, which in a great number of the nations to the south forms the largest racial element. To put it another way, there are relatively few Latin Americans today whose ancestry is free from some racial mixing.

Or take the colonial background of Latin America as compared with ours. In general we were the fortunate heirs of a relatively liberal political, economic, and religious system born from the hundreds of years of development and travail in the English motherland. But what of Spain? She ruled her vast empire with as heavy a hand as any colonial power in history. Every official, indeed, every colonist, was circumscribed by such a monumental and detailed series of laws and regulations that his only freedom lay in disobeying the law. This pattern of disobedience to the law, although rather minute in the over-all colonial scene, did serve to establish a pattern which was fraught with danger for a stable future when these areas became independent. Every significant colonial official, viceroy, captain-general, bishop, even the mayor, was appointed by the Spanish Crown and was, almost without exception, a native Spaniard. Thus the American-born Spaniard was deprived of all training in selfgovernment except on the municipal council level, and was completely unprepared for the responsibilities which were his after the Spanish hand had been struck away.

ECONOMICALLY, too, Spain kept a stranglehold on her colonies in America. In the best mercantilist tradition she saw to it that her colonies served merely as producers of raw materials for the motherland and as markets for her finished products. Had even a tenth-part of the economic restriction applied by Spain to her colonies been applied by England to hers our revolution would have been launched at a much earlier date. As it turned out, when England finally did decide to advance hesitatingly along the mercantilist path with the Navigation Acts and similar legislation the American air was filled with shouts of "Hang George III!" and the waters of Boston Harbor received case after case of the East India Company's principal product. Here, too, the only escape for the Spanish colonist lay in circumventing the law, and smuggling became a finely developed art in Latin America. It still is.

There were no colonies of religious dissidents in colonial Hispanic America. Spain, "more Catholic than the Papacy," saw to it that only Roman Catholics received a license to travel to America. The relationship between State and Church was so close as to be scarcely distinguishable. The Royal Patronage (Real Patronato) granted to Ferdinand and Isabella by the Spanish Pope Alexander VI permitted to them and their successors absolute control over ecclesiastical affairs within their realms. No direct

communication was permitted between Rome and the Spanish clergy without the approval of the monarch. Every high church official was, in effect, appointed by the king. The control over religious affairs was so complete that it was quite true that no real distinction existed between heresy and treason.

Independence came as a heady wine to Latin America. In many areas the local population has never achieved the heroism and singleness of purpose evinced during that struggle which in ferocity, number of troops involved, distances covered, and obstacles overcome made our glorious Revolution somewhat pale in comparison. Once the bayonets had been sheathed the national leaders, almost to a man pure-white American-born Spaniards and not mestizos, turned to the task of launching these nations into their independent life. When the common enemy returned to Spain the shaky unity of areas and leaders melted away, and Latin America entered into a period of great unrest, rebellion, even anarchy, which in some regions has continued to exist to the present day.

With no knowledge whatever of republican government, constitutions by the dozens were adopted to last only so long as the party in power could successfully manipulate them to its own good. Dependence on the local caudillo (leader), usually a military man, became the rule, and personal struggles for power caused the countless revolutions and counterrevolutions (for example, six presidents in Mexico in one year) which make the college student electing Latin American history long for the peaceful days of Greece or Rome. And gradually during the latter part of the past century a mounting feeling of social injustice emerged when the Indian and mestizo began to ask why he was so very very poor, landless and underpaid, while the rich were so very very rich. Beginning with the social legislation of Battle y OrdÓñoz in Uruguay after 1903, and with the great social upheaval in Mexico after 1910 Latin America has continued to pass through a stage of raising up the peon from his semi-slavery and bringing down the great landowner from his feudal heights. This social revolution is still going on with increasing momentum.

BUT what of the current situation? One may well ask again what has happened to our relations with Latin America in the past few years when we had the comfortable thought that the Good Neighbor Policy, with its agreement not to interfere in the internal affairs of Latin America made good by the withdrawal of our Marines from various Central American and Caribbean countries, had solved forever our problems in that area and bound all 21 of us together in the mystic bond of Pan-Americanism. One writer has gone so far as to state that our Latin American policy has reached its greatest crisis since Mr. Monroe pronounced his famous Doctrine in 1823. Although that is patently an overstatement of the case, it remains true that "an agonizing reappraisal" of our policy appears to be called for. It is reported that Mr. Nixon came home with a bag-full of ideas to meet the complaints which were made to him not only by spittle-bedewing students but also by sober and sensible statesmen.

One of the most constantly recurring accusations made by student and statesman alike was our "coddling" of dictators. Specifically cited were our awarding of a Legion of Merit and then granting of a resident visa to the discredited dictator of Venezuela, Marcos Perez Jimenez, and our close collaboration with the dictator of the Dominican Republic, Trujillo. These dictators, and many others, are supported by their respective armies which are in turn supplied by the United States with weapons with which the suppression of civil liberties is continued. In many of these areas truly democratic elements find themselves stifled on every hand by forces supplied and, so they claim, encouraged by the very nation which claims to be the champion of world democracy.

ECONOMIC grievances were frequently voiced during Mr. Nixon's trip. The Latin American nations complain that during the war the United States, faced with a severe shortage of many commodities usually obtained in the Far East, came to them with hat in hand begging that production of oil, sugar, copper, tin, rubber, and so forth, be greatly increased. In response to this anguished cry from the good neighbor to the north marginal fields were planted to sugar, oil reserves were tapped and drained, marginal mines were opened. Then with the end of the war the roof caved in. North Americans turned their back on their wartime suppliers, and once again went to other world areas for the bulk of their purchases of these commodities. A violent dislocation of the economy of many Latin American areas followed.

Financial aid from the United States was not the answer, for here again the Latin Americans complain that they have not received fair treatment from us and are quick to cite statistics to prove their point. Out of $57,662,000,000 in foreign aid granted by the American government in the years 1945-1957 only $1,107,000,000 was allocated for the American republics while $1,095,000,000, almost as much, was sent behind the Iron Curtain to European Communist countries. Moreover, most of the money sent to the Communists was in the form of grants, i.e., not to be repaid, while well over half of the money sent to Latin America was in the form of loans to be repaid with interest. A Colombian complained last year that although his country was in dire economic straits and had been the only Latin American country to send a fighting unit to Korea, the amount of aid sent to Communist Poland just in 1957 was vastly greater than the entire amount of aid granted his country since 1945. Latin Americans look at the booming prosperity of the former enemies, Germany and Japan, a prosperity which rightly or wrongly they feel was in a large measure created with United States help, and ask themselves what it profited them to cooperate so closely with us during the war.

Latin Americans also complain about the activities of many American companies operating in their area. In many of the republics a single company, or companies engaged in similar activities, have a virtual stranglehold on the nation's economy. They are often the nation's largest employers and its largest producers of goods for export. In the past they have often gained their position through ruthless business methods which have driven smaller local producers to the wall, and although most American companies now have a much more enlightened policy in this regard, some of the old methods linger on and provide the extreme nationalists and Communists with one of their prime targets.

Another of the favorite themes of the Communists with which many Latin Americans agree is that of racial discrimination by North Americans. Recently a Mexican newspaper published a photograph of a sign on the door of a Texas restaurant which read, "Dogs and Mexicans, Keep Out!" A Honduran labor newspaper reported that two Negro labor leaders from the North Coast of Honduras went to the capital, Tegucigalpa, and were refused admission to one of the leading hotels on the grounds that the owner was attempting to build up his business with American tourists, and they did not like Negroes. These incidents, and scores like them, are difficult for us to counter.

Latin Americans still think of the United States in terms of the "Colossus of the North." They continue to cling to the belief best expressed by the Uruguayan author, José Rodó, in his Ariel, that the United States is a Caliban, uncultured and materialistic, while Latin America is an Ariel, the embodiment of man's higher spiritual aspirations. All these complaints, whether real or imagined, are used by the Communists, whose activity in Latin America is currently greatly on the increase. Taking advantage of the vulnerability of the United States position in many of these matters, the Communists, both the local parties and the Soviet Union itself, have redoubled their efforts to maximize the resentment against all forms of "Yankee imperialism." Local Communist parties, although ostensibly outlawed in most of the republics, are seeking and finding alliances with the nationalists, while the Soviet Union is making a concerted drive to capture a much larger share of Latin America's trade at the expense of the United States and other Western powers. Witness the recent, and almost impossibly tempting, offer of the Russians to take a large part of Brazil's mounting glut of coffee in exchange for the oil which Brazil so desperately needs. It is only the unswerving faithfulness of the present government of Brazil to the West that has prevented an eager acceptance of this attractive offer.

IN recent months Congressmen, publicists, and experts, real and self-styled, have offered suggestions concerning reforms which might be made in our Latin American policy. Certainly we should no longer take Latin America for granted. The days when the United States could count on their unquestioning support for each and every move it made in world affairs are gone forever. The United States must become more aware of that area's genuine problems and grievances, and treat them with a sympathy which is their just due. We can no longer afford to relegate Latin American requests for aid to the very bottom of the priority list. We must abandon our erratic tariff policy toward the products on which the economic life of many of these republics depends. The sudden threat of an increased tariff on copper, lead, and zinc this past year caused a severe panic in Chile and Peru. An assured tariff rate for, say, five years, and the abandonment of the practice of establishing quantitative quotas on many Latin American products would go a long way toward stabilizing many regional economies.

In working with Latin American nations we must treat them with respect and as equal partners. We should be less reluctant to provide long-term, low-interest credits for sound governmental projects. Our constant harping on the primary role for private capital falls rather sourly on ears which have heard us so quickly answer the pleas for help from Communist Poland and Yugoslavia. Increased investment of private capital, however, can supplement, but not supplant, long-term aid from the United States government. These nations offer a happy promise for private investment which can do so much to aid in a diversification of their economies and a lessening reliance on a relatively few products for their national livelihood. To counter the Communists, who point to the rapid industrialization of Soviet Russia under state socialization as the only logical answer to their aspirations, we must continually point out that we are a people who achieved industrialization without sacrifice of personal freedom. Above all, we must not brand every genuine movement for social progress in Latin America as Comnunist. We have been much too prone in the past to ally ourselves with the so-called "stable" elements of the various republics which in many cases are merely the vestigial remnants of an old order of feudal barony.

These are a few of a great many suggestions which might be made to improve our relations with Latin America. One hopes that the shock at Mr. Nixon's treatment may have been deep and lasting enough to cause our government to recast this policy in the light of the swiftmoving events of today. One thing is certain, unless we do pay more attention to our southern neighbors we stand in grave danger of having some of these republics start along the road toward Communism. As Secretary of State Dulles himself has admitted, "If we don't look out, we will wake up some morning and read in the newspapers that there happened in Latin America the same kind of thing that happened in China in 1949."

We do have in much of Latin America a great reservoir of good will for us and an appreciation that the United States is engaged in a world struggle in which the basic ideals of all America, North, Central, and South, are at stake. It is up to us, as individuals and collectively as a nation, to do all in our power to eliminate where possible the growing frictions between ourselves and the republics to the south. It is an urgent task, but not an impossible one. If something of the same energy and imagination that is currently being applied to the question of the Middle East were applied to Latin America, we could all look forward with confidence to a rapid restoration and even improvement of what used to be our "Good Neighbor Policy."

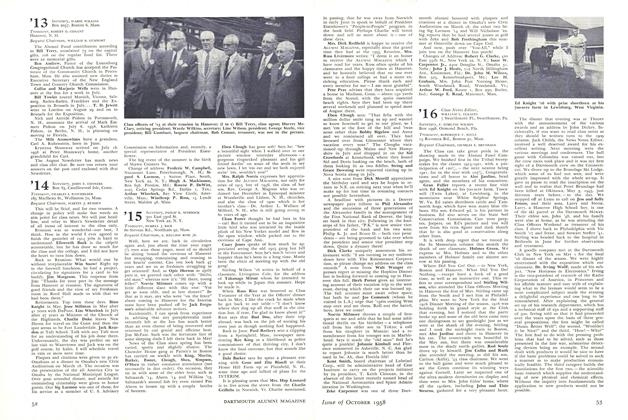

Professor McCornack

The Author: At the request of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, Professor McCornack has written this article presenting some of the views expressed in the talk he gave in the Hanover Holiday program last June. Latin America is a field in which he first became interested as a Senior Fellow and in which he now specializes as a member of Dartmouth's History Department. After graduate work at Harvard and Navy service in Panama, he joined the faculty in 1947, took his Ph.D. at Harvard in 1949, and became assistant professor in 1951 and full professor in 1957. He served in the State Department in 1951-52 and received a Ford Foundation Fellowship for study in Latin America in 1954-55. His most recent trip to Latin America occurred in the summer of 1957. Professor McCornack bears a name famous in Dartmouth football annals. His father, the late Walter E. McCornack '97, was captain and quarterback in 1895 and 1896, and was head coach in 1901 and 1902.

"We should no longer take Latin America for granted. The days when the United States could count on their unquestioning support for each and every move it made in world affairs are gone forever."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

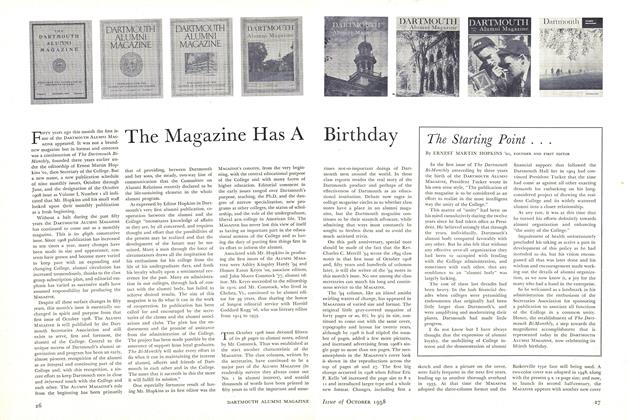

FeatureThe Magazine Has A Birthday

October 1958 By C.E.W. -

Feature

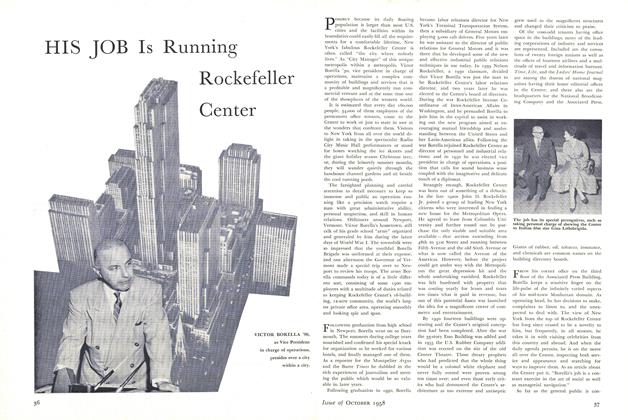

FeatureHIS JOB Is Running Rockefeller Center

October 1958 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureIndependence in Learning

October 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

October 1958 By LT. FREDERICK H. STEPHENS JR., CHARLES B. BUCHANAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

October 1958 By JOHN HURD, LINCOLN H. WELD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

October 1958 By WILLIAM L. CLEAVES, F. STIRLING WILSON, RODERIQUE F. SOULE1 more ...

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Cold War and Liberal Learning

November 1961 -

Feature

Feature75 Years of Helping Students

APRIL 1971 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFLUDE MEDAL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

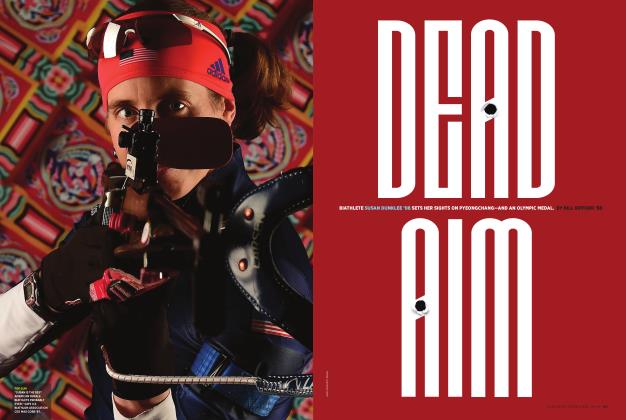

FeatureDead Aim

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2018 By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1968

JULY 1968 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY