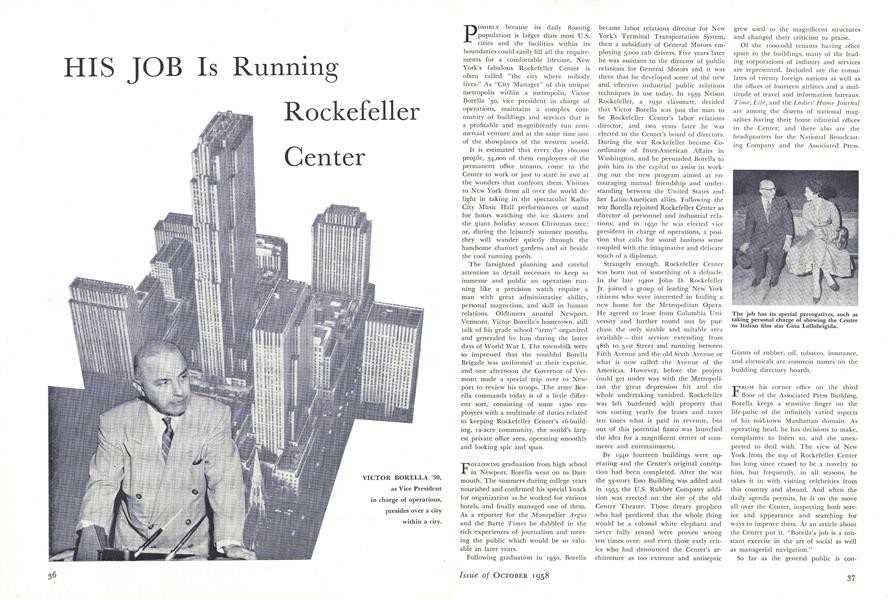

POSSIBLY because its daily floating population is larger than most U.S. cities and the facilities within its boundaries could easily fill all the requirements for a comfortable lifetime, New York's fabulous Rockefeller Center is often called "the city where nobody lives." As "City Manager" of this unique metropolis within a metropolis, Victor Borella '30, vice president in charge of operations, maintains a complex community of buildings and services that is a profitable and magnificently run commercial venture and at the same time one of the showplaces of the western world.

It is estimated that every day 160,000 people, 34,000 of them employees of the permanent office tenants, come to the Center to work or just to stare in awe at the wonders that confront them. Visitors to New York from all over the world delight in taking in the spectacular Radio City Music Hall performances or stand for hours watching the ice skaters and the giant holiday season Christmas tree; or, during the leisurely summer months, they will wander quietly through the handsome channel gardens and sit beside the cool running pools.

The farsighted planning and careful attention to detail necessary to keep so immense and public an operation running like a precision watch require a man with great administrative ability, personal magnetism, and skill in human relations. Oldtimers around Newport, Vermont, Victor Borella's hometown, still talk of his grade school "army" organized and generaled by him during the latter days of World War I. The townsfolk were so impressed that the youthful Borella Brigade was uniformed at their expense, and one afternoon the Governor of Vermont made a special trip over to Newport to review his troops. The army Borella commands today is of a little different sort, consisting of some 1500 employees with a multitude of duties related to keeping Rockefeller Center's 16-building, 12-acre community, the world's largest private office area, operating smoothly and looking spic and span.

FOLLOWING graduation from high school in Newport, Borella went on to Dartmouth. The summers during college years nourished and confirmed his special knack for organization as he worked for various hotels, and finally managed one of them. As a reporter for the Montpelier Argus and the Barre Times he dabbled in the rich experiences of journalism and meeting the public which would be so valuable in later years.

Following graduation in 1930, Borella became labor relations director for New York's Terminal Transportation System, then a subsidiary of General Motors employing 5,000 cab drivers. Five years later he was assistant to the director of public relations for General Motors and it was there that he developed some of the new and effective industrial public relations techniques in use today. In 1939 Nelson Rockefeller, a 1930 classmate, decided that Victor Borella was just the man to be Rockefeller Center's labor relations director, and two years later he was elected to the Center's board of directors. During the war Rockefeller became Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs in Washington, and he persuaded Borella to join him in the capital to assist in working out the new program aimed at encouraging mutual friendship and understanding between the United States and her Latin-American allies. Following the war Borella rejoined Rockefeller Center as director of personnel and industrial relations; and in 1950 he was elected vice president in charge of operations, a position that calls for sound business sense coupled with the imaginative and delicate touch of a diplomat.

Strangely enough, Rockefeller Center was born out of something of a debacle. In the late 1980s John D. Rockefeller Jr. joined a group of leading New York citizens who were interested in finding a new home for the Metropolitan Opera. He agreed to lease from Columbia University and further round out by purchase the only sizable and suitable area available - that section extending from 48th to 51st Street and running between Fifth Avenue and the old Sixth Avenue or what is now called the Avenue of the Americas. However, before the project could get under way with the Metropolitan the great depression hit and the whole undertaking vanished. Rockefeller was left burdened with property that was costing yearly for leases and taxes ten times what it paid in revenue, but out of this potential fiasco was launched the idea for a magnificent center of commerce and entertainment.

By 1940 fourteen buildings were operating and the Center's original conception had been completed. After the war the 33-story Esso Building was added and in 1955 the U.S. Rubber Company addition was erected on the site of the old Center Theatre. Those dreary prophets who had predicted that the whole thing would be a colossal white elephant and never fully rented were proven wrong ten times over; and even those early critics who had denounced the Center's architecture as too extreme and antiseptic grew used to the magnificent structures and changed their criticism to praise.

Of the 1000-odd tenants having office space in the buildings, many of the leading corporations of industry and services are represented. Included are the consulates of twenty foreign nations as well as the offices of fourteen airlines and a multitude of travel and information bureaus. Time, Life, and the Ladies' Home Journal are among the dozens of national magazines having their home editorial offices in the Center; and there also are the headquarters for the National Broadcasting Company and the Associated Press. Giants of rubber, oil, tobacco, insurance, and chemicals are common names on the building directory boards.

FROM his corner office on the third floor of the Associated Press Building, Borella keeps a sensitive finger on the life-pulse of the infinitely varied aspects of his mid-town Manhattan domain. As operating head, he has decisions to make, complaints to listen to, and the unexpected to deal with. The view of New York from the top of Rockefeller Center has long since ceased to be a novelty to him, but frequently, in all seasons, he takes it in with visiting celebrities from this country and abroad. And when the daily agenda permits, he is on the move all over the Center, inspecting both service and appearance and searching for ways to improve them. As an article about the Center put it, "Borella's job is a constant exercise in the art of social as well as managerial navigation."

So far as the general public is concerned, Rockefeller Center is far more than a nerve center for commerce and industry. It is the entertainment and tourist attraction par excellence; the famous Radio City Music Hall performances, fascinating exhibitions, and myriad displays throughout the year make it a virtual wonderland for the tourist and an ever-changing spectacle for even the most blase New Yorker.

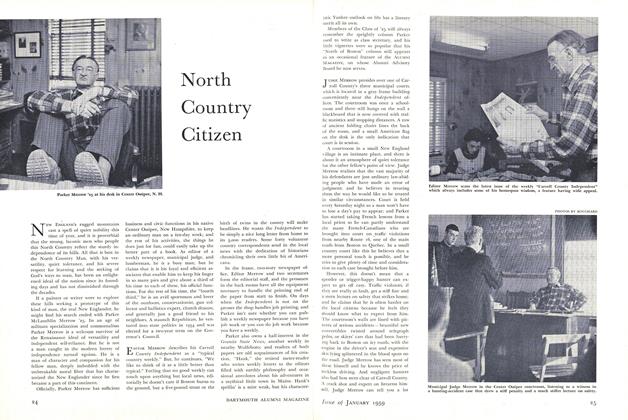

The huge Christmas tree is selected every year for its height and perfection from a forest somewhere in the country and trucked to the Center with painstaking care. As Borella feels, it must not be outsized in any proportion, but be "a perfect gem of a tree," beautiful to behold. New Yorkers and tourists, the humble, the great and the would-be great take time out from their busy Christmas seasons to stop for a minute and stare in common admiration at the towering evergreen so brightly decorated - truly a symbol of the nation's Christmas. Many get their toes a little cold with the December chill but linger a bit longer to listen to the hundred-voice Rockefeller Center choristers, talented volunteers chosen from among tenants and employees.

Multitudes of carefully cultivated flowers, scattered through the man) gardens and roof pavilions, change with the season, beginning with Easter lilies in the spring and ending with the traditional fall chrysanthemums. Many a tired New York office worker looks forward to a cooling lunch hour spent sitting by the floral-lined brook running down the "Channel" - so called because it lies between the British and French buildings - that wide pavilion walk gently sloping down into the heart of the Center from Fifth Avenue. These gardens are so loved and respected by the public that the usual perfunctory "Do n0t..." signs are superfluous; the only known case of vandalism was perpetrated by a tipsy visiting fireman who lifted an inviting fresh pineapple from a tropical display.

THE Center's daily transient population offers, as do its permanent tenants, a cross-section of the world, striped ties beside turbaned heads and sandled feet; and Victor Borella is the man to see that all receive the same impressive service. His sincere cordiality well complements the quiet, subtle efficiency found everywhere from the top of the towering RCA Building to the lowermost sub-basement supply depot, and his aim is "to make the Center an institution in the sense of being kind of a community center." For an enterprise of its size and scope, Rockefeller Center's public relations are amazingly good, and most of it revolves around cancelling out potential problems before they can even start and, as Borella says, "avoiding the undignified." A log placed on his desk each morning records every event out of the ordinary that occurred during the previous 24-hour period. Accidents and incidents are isolated immediately, their cause determined and, if necessary, remedied.

Not far from Borella's office there is a large control board which makes it easier to keep track of what is going on throughout the farflung reaches of the Center. A small army of watchmen and maintenance personnel patrol and service the buildings continuously, and the large cleaning force covers every cleanable and polishable inch in a regular pattern. The size of this cleaning operation is difficult to comprehend; the force uses monthly, 2800 pounds of soap, 500 gallons of wax and 110 gallons of brass polish. Every evening at 7 o'clock the 620 cleaners assemble and move out according to a detailed plan, keeping the insides of every building as bright and fresh as when they were built.

Unusual problems involving maintenance are solved by the staff with energy and imagination. When the huge Prometheus statue reposing in the sunken fountain in the heart of the Center was growing dull and needed a new coat of gold leaf, the staff hoped to have it ready for the Easter display, but cold weather continued to plague their efforts to make the leafing stick correctly. So with the usual energy a complete wooden shelter was built around the huge statue and the temperature inside controlled, allowing work to proceed in time for the Easter opening.

As even smug New Yorkers will tell you, coming from the rest of Manhattan's often dilatory and begrudging service into Rockefeller Center, where the employees seem to take pride and pleasure in serving the public, can be a surprising and delightful change. There is a certain esprit de corps among the employees and this is possibly reflected in the lack of direct strikes against the Center since Nelson Rockefeller first assumed the president's duties in 1938 — though some of the foreign consulates contained in the buildings are occasionally picketed by their irate nationals for a variety of reasons. Being an old labor relations man himself, Borella naturally keeps close touch on the pulse of opinion among his incredibly varied types of employees. After the war when "new-look" skirts dropped several inches and petticoats naturally followed suit, many an unhappy cleaning woman found her lace protruding beneath the old-style work uniform into which she changed every morning. Hearing of this minor tragedy of feminine decor, Borella immediately ordered all work uniforms to be altered by the Center, fitting the new requirements of high fashion and soothing feminine pride.

As host to millions, Borella is a very busy man, but he still finds time for Dartmouth, as chairman of the Class of 1930 and a member of the Hanover Inn Board of Overseers. And in 1951 he was awarded the Freedoms Foundation Medal for his stirring commencement address before the graduating class of Newport, Vermont, High School.

There is rarely a day goes by in Rockefeller Center that doesn't require some important decision on his part or the planning of a new project to improve the Center's service to the public. It is this thoughtful planning and attention to detail by Victor Borella and his staff that maintain the Center's universal reputation for high standards and good taste, and for that matter, as a place that's an awful lot of fun to visit.

VICTOR BORELLA '30, as Vice President in charge of operations, presides over a city within a city.

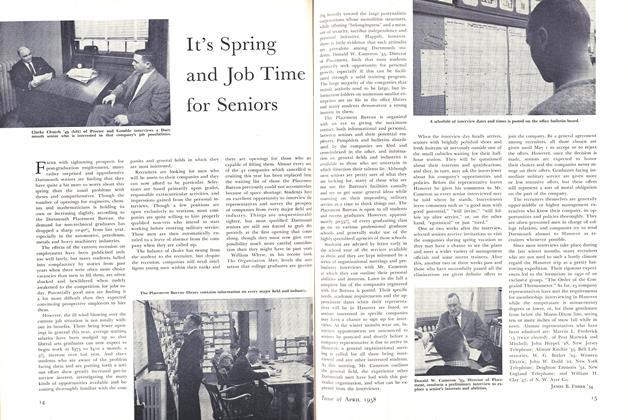

The job has its special prerogatives, such as taking personal charge of showing the Center to Italian film star Gina Lollobrigida.

Two special and famous attractions during the Rockefeller Center year are the annual Christmas tree and Easter lily displays. The tree shown, a 64-foot white spruce, was the gift of the State of New Hampshire.

Two special and famous attractions during the Rockefeller Center year are the annual Christmas tree and Easter lily displays. The tree shown, a 64-foot white spruce, was the gift of the State of New Hampshire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureUnrest in Latin America

October 1958 By RICHARD B. McCORNACK -

Feature

FeatureThe Magazine Has A Birthday

October 1958 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureIndependence in Learning

October 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

October 1958 By LT. FREDERICK H. STEPHENS JR., CHARLES B. BUCHANAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

October 1958 By JOHN HURD, LINCOLN H. WELD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

October 1958 By WILLIAM L. CLEAVES, F. STIRLING WILSON, RODERIQUE F. SOULE1 more ...

JAMES B. FISHER '54

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1961 -

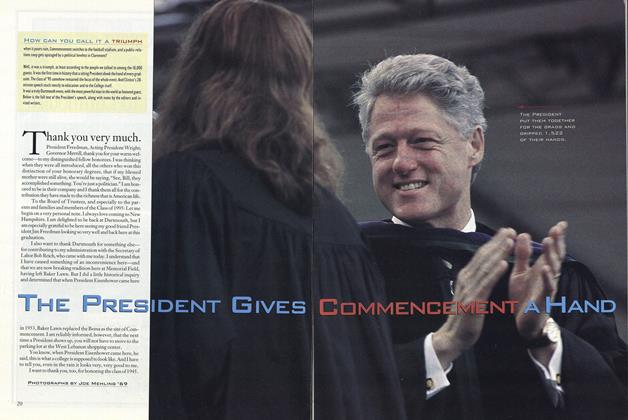

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe President Gives Commencement a Hand

September 1995 -

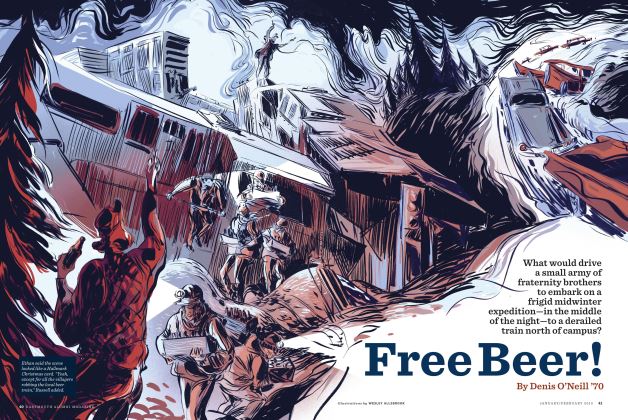

Feature

FeatureFree Beer!

JAnuAry | FebruAry By Denis O'Neill ’70 -

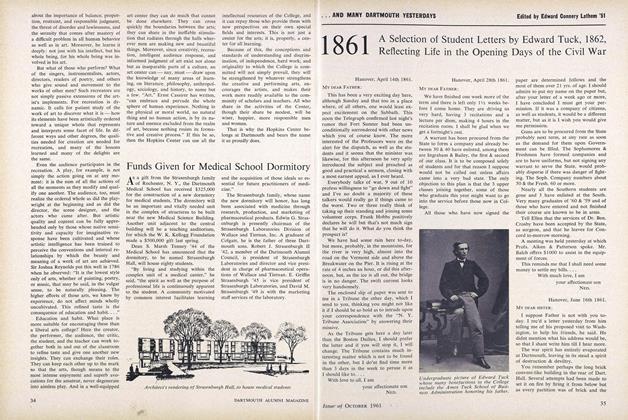

Feature

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

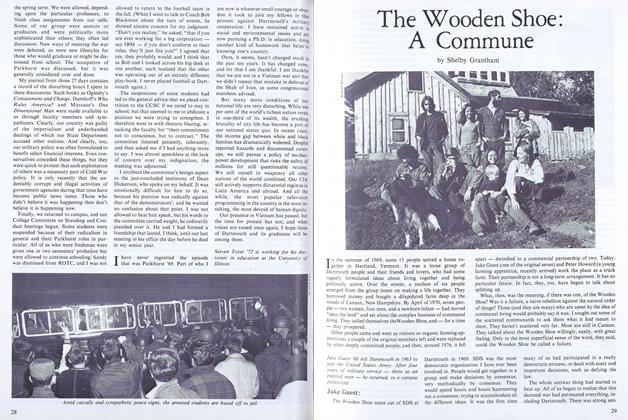

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

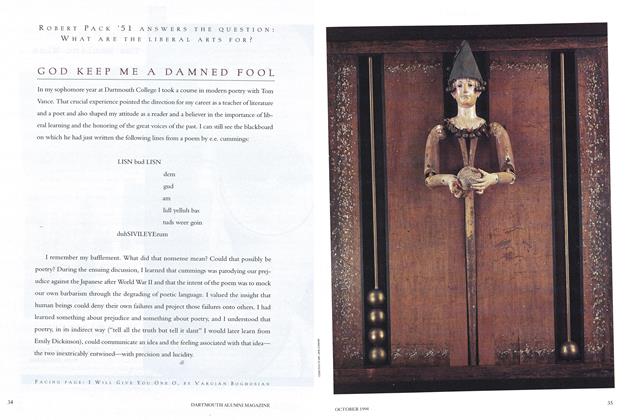

FeatureGOD KEEP ME A DAMNED FOOL

OCTOBER 1994 By Varujan Boghosian