It was the fall of 1965, and New York City newspapers were tied up in a second prolonged strike within three years. CHARLES H. BROWN '35, "a little restless" after 20 years as a foreign correspondent and editor for Newsweek and TheNew York Times, was in the offices of the International Executive Service Corps, talking with its public relations director. The man, it turned out, was looking for his own successor.

When the strike was over, Brown resigned from The Times and joined IESC, which is affectionately known as "The Paunch Corps." As vice president for public relations, he has since been spreading the word about the remarkable pioneering program organized by U. S. businessmen to lend America's managerial know-how to developing countries. He edits a monthly newsletter and brochures about the Corps' aims and procedures and handles press relations, keeping newspapers, trade journals, corporations, and general publications abreast of IESC activities.

The Corps recruits top-flight executives, mostly retired, for volunteer short-term missions to counsel young and growing enterprises on problems of production, engineering, administration, and marketing. Its file of over 7000 potential volunteers represents an unparalled reservoir of managerial experience.

Since IESC was born in 1964, 2361 projects have been completed, with 156 currently under way. More than 1500 men, 12 of them Dartmouth alumni, and 14 women have been sent to 46 countries in Central and South America, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean area. Yugoslavia is the latest—and a significant—addition to the growing list of countries inviting the service.

Harrison F. Dunning '30, retired chairman of the board of the Scott Paper Company, interrupted an IESC mission to Brazil to join his fellow Dartmouth Trustees in Hanover in November to share in the historic decisions on coeducation and year-round operation.

Projects originate with a request from the firm seeking help. When New York headquarters approves the project, in large part on the basis of potential economic impact on the local community, IESC recruiters search out the man with the best qualifications for the job. Most clients are private companies, a few government agencies. All private firms must be more than half locally owned.

Volunteers receive no pay, only transportation and living expenses for themselves and their wives. Age is no barrier—the oldest volunteer spent his 76th birthday on the job—and there is no language requirement. Competence and experience, patience and adaptability, willingness to live overseas, and the desire to serve, Brown says, are the criteria for selection. Missions are kept deliberately short—the average is three months—to reduce the risk of dependence of client on volunteer or the temptation to manage rather than advise.

Although Brown sees most of the volunteers in New York before they leave, orientation is minimal. "IESC volunteers are sent to a specific country to do a specific job," he points out. "They all know their business, or they wouldn't be going, and there's little we can tell them."

Charles Brown—"Chuck" when he was an undergraduate, cornering the market in debating and oratory honors—is a "PR man's PR man." He dispenses information about IESC with infectious enthusiasm and computer efficiency:

• its origins in David Rockefeller's call for "task forces in free enterprise" to developing countries at a 1963 International Management Conference;

• its support by fees from clients, contributions from corporate sponsors in the U. S. and beneficiary countries, and "no-strings" foreign aid funds;

• its leadership, with Rockefeller, the first chairman, suc- ceeded by George D. Woods, former head of the World Bank, and Frank Pace Jr., L.L.D. '51, former Secretary of the Army and Chairman of General Dynamics, as chief executive officer;

• its success, testified to by the satisfaction of volunteer and client alike and a spate of imitators among the industrailized nations.

"Charley" Brown, as he is now known to his occasional dismay, has a postgraduate history that would move the most adventurous of the new generation to envy. He worked his way around the world "by boat train and bullock cart, hitchhiking and plain hiking" the first year out of college. Five years of writing for newspapers and magazines, one as a free-lancer in the Middle East, preceded three years in the Army, from which he emerged with the Legion of Merit, the Bronze Star, and a flock of campaign ribbons representing the North Africa-Germany trail.

He joined Newsweek as an assistant foreign editor in 1945, was sent to Germany as Frankfurt bureau chief and later to set up the Bonn bureau. He and his wife, a Newsweek colleague, were married in Paris. Newsweek brought him back to New York in 1952 as associate editor for foreign and national affairs. Three years later he went to The Times as a Sunday magazine editor.

He admits to having trouble with his name. A substantia, percentage of people find it irresistible to ask, with a blinding flash of originality precisely like someone else's five minutes earlier, "How is Snoopy?"

He would rather talk about "the Paunch Corps."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEDITING ROBERT FROST

February 1972 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Growing Threat to Privacy Posed by Computer Data Banks

February 1972 By ROBERT P. HENDERSON '53 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSymphony Conductor

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSnow Engineer

February 1972 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1972 By MARK HELLER '70

Features

-

Feature

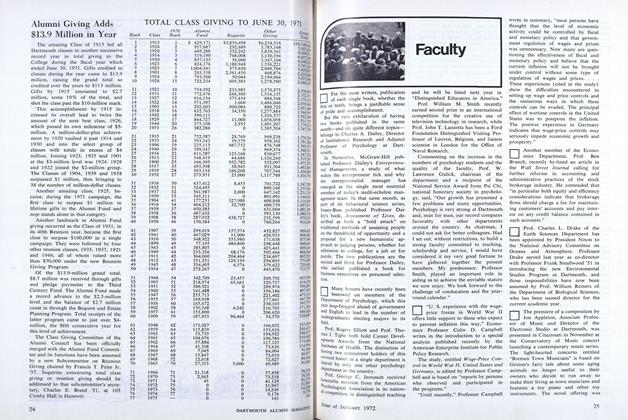

FeatureAlumni Giving Adds $13.9 Million in Year

JANUARY 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO CHOOSE A LAWYER

Sept/Oct 2001 By BARBARA MURPHY '79 -

Feature

FeatureA Course of Reading for Dartmouth Men

December 1955 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

FeatureMinimum Standards

APRIL • 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Feature

FeatureIt's Spring and Job Time for Seniors

By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO CONVINCE YOUR CLASSMATES TO FORK IT OVER

Jan/Feb 2009 By TROY STEWART '07