Professor Brown's talk about Dartmouthand its faculty was originally presented tothe Class of 1932 at its 25th reunion. Itspublication in the Alumni Magazine hasbeen urged by many persons who heardit: an idea the editor can claim to haveacquired independently the moment heread the text. The talk, printed here withProfessor Brown's permission, is a remarkably astute and instructive analysis of theteaching side of the College.

CHENEY PROFESSOR OF MATHEMATICS

THE Class of 1932 was a fortunate class. It came to Dartmouth at a very good time. Let me summarize the accomplishments of the half-dozen years before the class arrived in the fall of 1928: (1) A selective system for admission had been put into operation, a system that really worked; (2) there was a new curriculum, with reasonable distribution, reasonable freedom of eleetion, and a strong major; (3) there was a new library which was, and still is, about the best of its kind; (4) there had been built up for this new and larger Dartmouth a solid core of young, enthusiastic assistant professors and instructors.

It was a new college that the Class of 1932 came to: old in traditions, but very new in spirit.

What makes a college new? This is the question I want to examine and try to answer. Why was Dartmouth old in 1890 and new in 1895? Why was she new in 1928? What is she today? What makes a college new?

It isn't the students. They respond, they reflect a change, but they do not cause it.

It isn't the alumni that make a college new - although they can mightily help, and under the wrong conditions, mightily hinder.

Leadership you must have. An outstanding president, backed by a competent and understanding board of trustees. This is necessary, but it is not enough.

For a college to be new, you must have a good faculty. That may work. It will work if you have a great faculty.

From which you may gather that I am going to say a lot about the faculty of Dartmouth College. You are very right. As responsible alumni you know a good deal about many aspects of the College. Possibly the phase you know least about is the faculty. In addition to undergraduate contacts, some of which have become blunted, and some of which have become sharpened over the years, you have three pieces of positive information:

(a) it is a funny, funny faculty; (b) it sleeps in trundle beds; (c) it indulges in unmentionable orgies in Leb and the Junction.

Certainly it is funny. As for the trundle beds, Rand's Furniture Store reports that their sale has fallen off the last few years - apparently another old tradition failing. But I do want to enter a mild protest against the orgies in Leb and the Junction. Perhaps I don't know how to go about this business of organizing orgies. The most desperate thing I have ever succeeded in doing is to buy a bottle of Scotch for home consumption.

Dartmouth has been old much more of the time than she has been new. She was born old. Eleazar Wheelock brought an old, old college to Hanover. The faculty was old, the Gradus ad Parnassum was old, the Bible was old, the drum was old, even the whole curriculum was old. The faculty in particular remained old. It is true that there were a few great teachers, and a very few scholars; and in all charity I must say that was purely accidental. The average was mediocre, and the depths were abysmal. In conservatism and orthodoxy, the Dartmouth faculty exceeded the faculty of any other college in New England.

Dartmouth was never new until William Jewett Tucker assumed the presidency in 1893. He caught the imagination of the student body, fused the alumni into a loyal unit, and expanded every phase of the College. Every one talked about the "new" Dartmouth; she was new. He did one more thing: he brought into the faculty William Patten, John Poor, Charles Darwin Adams, David Wells, Frank Dixon, Fred Emery, Craven Laycock, Ashley (Dutch) Hardy, Herbert (Eric the Red) Foster, Ernest Fox Nichols, Louis Dow, Gordon Ferrie Hull, and Leon Burr (Cheerless) Richardson.

That was not merely a good faculty; that was a great faculty. Give Dr. Tucker all credit for seeing that a great college must have a great faculty. Give him credit for his ability to go out and assemble such a faculty. There is still much room for credit for a great faculty which realized Dr. Tucker's dream.

New things don't stay new - not without a lot of effort. The newness had worn off when Ernest Martin Hopkins took over in 1916. And before he could do much, there was a World War on our hands. Once that was over, things started to click.

The College grew amazingly, outrageously. Some completely new system of admission had to be developed, and was. The faculty had to be expanded, enormously. But teachers must have some assurance that this is a good place to come to. At that time a Department had a permanent head, and rather incredible powers were delegated to him. He could hire and fire and, within limits, set all salaries. He arranged all schedules, planned the courses, picked the textbooks. That's not a good set-up for an ambitious young instructor with ideas. Further, there were two or three Departments where the autocracy of the head made conditions quite intolerable. So the Trustees, at the instigation of their young president, abolished the system, installed a rotating system of chairmen, and gave the humblest instructor the same voting rights as the most august professor. This plan was more liberal than that which obtained at most of the comparable institutions. As a result of this, from 1919 to 1928, Dartmouth skimmed off a good deal of the cream from the Eastern graduate schools, and a vigorous, competent, young faculty with only a sprinkling of veterans greeted the entering Class of 1932 in September 1928.

That faculty stuck. Statistics are the last thing you want to listen to; but when I say that faculty stuck, I could back it with an impressive array of figures. Teachers went to Amherst, shifted to Brown, shifted to Harvard, shifted to Chicago. Teachers came to Dartmouth and stayed. A liberal policy of promotion and tenure, freedom so genuine you didn't have to talk about it all the time; these and other factors made Dartmouth an attractive prospect for a teacher at the start of his career. This Hanover Plain is a curious thing once it gets its hooks into you. You damn the climate, damn the B & M, triply damn the month of March - and stay.

ALL of this in retrospect had its good and its bad points.

A job on the Dartmouth faculty was safe and secure. That was good. But it was too safe and too secure, and that was not so good. During the period 1920-1945, it was unusual for an instructor or assistant professor to be refused a reappointment, and if he stayed on, as most of them did, he was eventually promoted to a full professorship. Although the Trustees have the final authority in all such matters, it is the older members of the faculty who have the real responsibility; and it was we who made the mistakes.

At Dartmouth in the twenties and thirties there were too many promotions, and too many men received tenure. The reasoning back of some of these promotions was wrong. "A has been in the Department longer than B. B is much the better man, but harmony will be better preserved if we promote A this year and B a few years later." "C has been with us 15 years. He isn't any ball of fire, but within his limitations, he has worked faithfully. We can't fire him after all these years. Every one will feel better if we promote him." "D doesn't really rate a promotion. But he has an offer from Podunk, and he says he won't stay unless he is promoted. It will take time and money to go out and hunt up a replacement, and it's such a nuisance. It's so much easier to just promote him."

A little too much we followed the line of least resistance. There were times when we paid just a little too high a price for harmony.

And so the new faculty of the 1920's stayed on, and were promoted. Mind you, it was not a mediocre faculty; it was a good faculty; and yet somehow it missed being a great faculty. It had lost just a touch of the fresh, new feeling of 1928. And the main reason for this brings us into a very difficult question - the question of teaching and research. This is tricky, and you don't get a mathematical answer to this question.

A community of scholars must do two things: it must teach and it must create. Every scholar in the community must teach, or create, or both. The community is judged by the sum of their achievements.

Now it is silly and wrong oversimplification to say that colleges should teach, and graduate schools should do research. Both must do both. The problem is one of shading and balance.

The words teaching and research are supposed to be dynamite. Dynamite is a very useful article. In addition to blowing up things which need to be blown up, dynamite furnished the money which led to the Nobel prizes.

For many scholars, research is the biggest thing in life. Teaching is incidental, if that. The two greatest mathematicians who ever lived were hopeless flops as teachers. Sir Isaac Newton, required to give lectures at Cambridge, delivered them to empty halls. Karl Friedrich Gaus simply refused to have any pupils, claim, ing (and with some justice) that no one could profit from his instruction. For the great big men, research is the whole story They grudge the time and effort spent in teaching, and even today (you might not know this one) there are curious methods of avoiding teaching, of which full advantage is taken. This may be expensive but it doesn't do very much actual harm.

But when they say every young scholar should take them as a model; when they demand all the plums; when they plan ridiculous elementary courses for some one else to teach; and when they urge young instructors deliberately to avoid getting a reputation as a good teacher because "it will hurt your career"; by this time the situation calls for dynamite.

At the other extreme is the man whose life is one long devotion to teaching. He himself, he likes to tell you, was once tempted by the siren of research; but since no man can serve two masters, he chose the greater, the nobler career of teacher. He explains that no one is worthy the name of teacher if he squanders his energy on creative writing. He himself devotes all his time to planning his teaching. He devotes so much energy to planning that he has precious little left when he finally enters the classroom. He prides himself on his carefulness and objectivity, and spends untold hours correcting hour examinations, and considering whether a split infinitive should cost the culprit 2 or 2½ points. Every college department loves a guy like this because he will take on all the tedious jobs that no one else wants. It is human nature to keep him and even promote him - but he is not an asset to a community of scholars, and you know it. You have to use dynamite. He is hurt, deeply hurt; he thought Dartmouth appreciated devotion to teaching, but he was wrong; Dartmouth is merely trying to ape the research universities. He loves Dartmouth, and hopes eventually that she will see the light before it is too late; in the meantime he forgives us. Is there anything more unpleasant in this world than being forgiven?

Now in the 1930's we made a very honest mistake. We knew that the universities gave an exaggerated emphasis to research. We knew that some colleges aped them. We knew that was wrong. But we swung just a little too far the other way. What we said to our young instructors was this: "First of all, Dartmouth asks you to give your best efforts to teach and inspire your students." That is not enough. We should have asked more. And so in the thirties there was a subtle slackening of the creacive urge at Dartmouth. We were content with too little.

This is one of those things that is not all black or all white. Suppose Mr. X wants to stay at a high-power research center; he has got to turn out half a dozen research jobs in five years. They don't have to be big ones; they don't even have to be the best measure of his powers. It would not be fair to use such words as assembly-line production; nevertheless, continuous tinuousproductivity is expected. Now suppose Mr. X wanted five years to mull over and digest a really big job. Under those conditions he might find Dartmouth a much better place for a creative scholar than a big research center.

This happened, and this is good: good for him and good for Dartmouth. But again, this isn't simple. High hopes and expectations sometimes bog down in lethargy. Many of us - and we should be ashamed of it, but there you are - many of us work better if the atmosphere of the place rather continually demands of us our best.

Statistics have no meaning here; we can only judge trends, and try to judge fairly. Personally I would say that we were content with too little, that we did not demand quite enough of ourselves and of each other, and that the Dartmouth faculty in those years never quite realized its full potential. The world of pugilism has an expression for this. In speaking of a fighter who has gone a long way, but has missed the top, they say, "He wasn't hungry enough."

So the faculty of the 1920's was here in 1940, older, more urbane, dedicated to teaching, full professors with tenure, much more tolerant than the faculty you knew, but definitely overloaded at the top. "What's wrong," you ask, "with having a top-heavy professorial group? Won't the instruction be better, and isn't that what we want?" Here at last is a question to which I think I know the answers. The first answer is that it costs too much. You have to pay professors more than instructors.

The second answer is allied to the first. You pay them more, and also you get much less out of them. You have no idea what a low minimum of actual teaching an established oldtimer can get away with. One freshman section of twenty, just to show that at Dartmouth we believe the best is none too good for freshmen. An advanced group of eight students who meet once a week to discuss, criticize, and compare. A couple of hours of conferences with honors students. Six hours a week: total of thirty students. If, in addition, he has any committee work, he will drop the freshman section.

My third reason is that even if a departmental group of professors is young, they aren't going to stay young, and they will almost certainly stagnate unless new blood is brought in.

If that doesn't seem to you at first thought a good reason, I'd like to enlarge on it. I give you my own Mathematics Department. In 1928 the Department consisted of five professors, four assistant professors, and two instructors. In 1945, seventeen years later, three of these eleven had died - the other eight were full professors. The important thing (and the bad thing) is that during those seventeen years, there had been no new blood added to the group.

Now let me make clear why that is a very bad thing. You may think of mathematics as a static thing invented by Euclid, unchanged and unchangeable. That isn't so; in the last thirty years the very foundations of mathematics have changed; symbolic logic has acquired an imposing structure; entirely new disciplines such as game-theory and linear programming have appeared from nowhere. Three of my younger colleagues have recently written a book on Finite Mathematics which is used in a course taken by 200 freshmen. In my considered judgment I am not competent to teach this course; and with this judgment I am quite sure my very competent young colleagues would concur, although they are too much the gentlemen to say so. The survivors of the old group have of course heard of these new developments. What we have never had until quite recently is a succession of young enthusiasts who would tell us that these things are good, and that a considerable amount of die traditional analytic geometry - calculus sequence is now archaic. It's hard to make changes unless you are prodded; and for years we didn't have any prodders.

I give you one example. Back in 1928 I taught that logarithms were important because they were so useful in computation. I should have known better; they weren't very useful even then; and since that time their usefulness has diminished almost to the vanishing point. Your instincts told you the less you had to do with the stupid things, the better. Your instincts were right, and I was wrong. If you fed logarithms into a modern computing machine, it would spit vacuum tubes at you.

No, a college faculty must not be static; it must continually draw in younger men, trained in different schools and in different disciplines. There must be constant flow: in and out.

I HAVE detailed some of the sins of omission of the faculty in the go's and early 40's. The Second World War found us with a solid core of full professors, and not much else. What there was of the younger group immediately girdled the earth. The older group stayed on and put in some exhausting work on the V-12 contingent. This was necessary; but it was dull plodding, and there was very little opportunity for creative work. When it was over, we were a tired lot, and we weren't any younger either. We remembered the old days, and we wanted to get right back to them. In this nostalgia there was a touch of staleness. In 1945 Dartmouth wasn't "new," as she had been in 1893 and in 1928. President Hopkins, a great leader who had brought the College even beyond the vision of Dr. Tucker, and who had seen the College through two World Wars, wanted a new man, a young man on the job. The faculty hated to see him go. We were just tired enough so that we were a little afraid of change, and we were afraid there would be changes.

There have been. Now I am not going to embarrass anyone on the scene by singing praises for jobs that are still not finished; and this will have to be in generalities. That tired old faculty bounced back. There has been remarkable and quite unexpected creativity. There has been added a brand-new younger group of impressive size, and slightly terrifying ability. The friction between the two groups has been remarkably little. Somewhat to their surprise, young instructors coming here have been immediately given considerable responsibilities, and urged to recommend and then put into effect rather sweeping changes. The word has gone out that Dartmouth is a good place for a young instructor with ideas. The methods by which this younger group have been recruited come as a bit of a shock to those of us who knew the old days when you boarded the noon train for Boston and picked up an instructor the way you would pick up a hat at Raymond's.

The simple fact is that today we have a good faculty which is on the verge of becoming a great faculty.

What do you do with a faculty after you have it; or more exactly, how does a faculty ultyoperate to achieve its greatest potential?

I assume you have read an article by Beardsley Ruml in the Atlantic Monthly entitled "Pay and the Professor." I should like to comment on two of his statements: "The teaching process is incredibly inefficient, and has not made the progress that might have been expected over the past fifty years." And again: "The really wasteful teaching is done in the classes that have between twenty and sixty members." These seem to me to be sensible, reasonable statements of fact. I would have said they were obvious, but some people seem to disagree.

I think I can make a point here only if I am specific. And I very much want to make the point. So I apologize only in a perfunctory way for talking about mathematics and myself. When I came to Dartmouth as an instructor, I was given five freshman sections of 24 men each. I'd like to explain that 24. There were two strong men in the Department at that time: Cy Young and Charles Nelson Haskins. Young was feeling on the subject that no section should ever have more than 18 men. The more rugged Haskins said you could handle 24. Young had been head of the Department, and had reduced the number of seats in the classrooms of old Chandler Hall to 18. When Haskins became chairman he had six more seats installed. Young succeeded him, and ripped them out. Haskins again followed Young and put them back. These were men of conviction, and action. As I said, I came here in a 24-year. It was slightly stultifying for me to give the same lecture five times in a row - and I really liked teaching —but it must have been deadly for the students who heard my fifth phonographicrecording. Still and all I did earn my keep, although it was not the best way to do it. 120 students a semester is a pretty fair load for a beginner. Every time I got a promotion the number of sections was reduced, and by the time I had been here ten years, I was teaching two or three classes, with an overall of something like thirty students a semester. There is something fundamentally wrong about that way of operating.

I won t detail all the experiments and changes; but I would like to tell you how we do it today. An experienced man in the Department lectures three times a week to a group of 125; then we supplement this with one hour of conference, handled by instructors or teaching fellows, in small groups of about 15.

That is what we do for the large freshman and sophomore courses. Advanced courses and Honors courses are all in very small groups. Honors courses, by the way, begin the very first semester of freshman year.

I know that 125 may sound pretty conservative to some of you. I've tried much larger, but they don't seem to work as well. I am a blackboard and chalk man; I know only the technique of the theatre; a flesh-and-blood actor in constant touch with his audience - responsive to their cheers, doubts, and hisses. Now if you have 400 students, there seems to be a loss of contact; and for another thing you have to write with the chalk sideways. I'm pretty conservative, and will settle for 125. experienced man can handle two such groups; that's only one lecture a day, plus organizational details. It's much better to have these groups in different subjects. If you repeat, you don't do as well the second time. But 250 students is a good fair teaching load. You feel that you are pulling your weight in the boat Of course, if one had a really modern lecture room, and projectors, and all kinds of gadgets, it would be sort of fun to take on the whole freshman class.

I am not competent to tell other Departments or Divisions what they should do. Mr. Ruml's generalizations on lectures and small discussion groups may be too sweeping. I don't know. But this basic thesis that our overall program is inefficient, and that the wasteful teaching is done in classes between twenty and sixty: this basic thesis is a clear call to action, And to a very considerable extent, we have anticipated this call.

Finally I am not going to describe in detail the new three-course three-term program. As responsible alumni of the College you are supposed to know about such things. Since I had nothing to do with it, I have no hesitation in saying that I think it is the greatest step forward in curriculum and organization that the College has ever taken. I believe it is more important than the other three big changes: the changes of 1880, 1902, and 1925. And my chief reason for saying this is that it differs from the big three in one very important aspect. Each of those laid down a new curriculum in finished form. When adopted, this was the curriculum that did in fact last (and with only minor changes) until the next big change. The curriculum seems to me to be in a very real sense a dynamic thing, whereas the others were static. If any one thinks he can heave a sigh of relief and say,

"Well, that's over for the next thirty years, let posterity worry about the next change," if any member of the Dartmouth family has that kind of an idea, he is very much mistaken.

Not that a new curriculum, or a new reading course, or a new anything else ushers in the millenium. Undergraduates are going to continue to be undergraduates; sophomores will continue to be sophomores; the month of March will not be abolished. But there will be big changes.

Now, please, I am no prophet. I am not defining College policy; and I am not sending up any trial balloons.

But a lot of things are being talked about. We talk about a five-day week. We talk about a grading system confined to Honor-Credit-Fail. We talk about an Honor System. We talk about fewer courses, large lectures, and a much greater use of teaching fellows and assistants. That means a smaller faculty. We talk about summer sessions. For juniors and seniors, we talk about two terms in residence, one term of independent study anywhere, and one term free. Brash upstarts, forgetting the traditions of 188 years, talk about co-education.

For once again, Dartmouth is new. By the same standards which showed her newness in 1893, and again in 1928, she is new.

What is newness? Newness is the assurance that you can do your job, plus a positive hunger for making the job bigger, and doing it better. Newness is second wind. Newness is that surge of power under which the dynamo gives out more than it takes in; under which the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It is I, a professional mathematician, who tell you that this can happen.

MY office is on the top floor of Dartmouth Hall. It resembles all the other faculty offices by being untidy but comfortable. I do have one special thing - a wonderful view of the campus. Now an office is the place to do business, but in the odd hours, the curious hours, it is the place to create - and dream.

You wouldn't think that a mathematician at seven o'clock on a winter morning would dream in his office. I tell you it is almost impossible to do anything else. Hanover and Dartmouth face the West. What we see are the rising foothills of the Green Mountain Range. Do you know those marvellous lines of Arthur Clough.?

And not by eastern windows only When daylight comes, comes in the light.

In front, the sun climbs slow, how slowly. But westward, look, the land is bright.

Winston Churchill quoted those at a time in World War II when he felt that England really could rely on the America to the westward for help. But we in Hanover see this so often. Fifteen minutes before the sun rises in Hanover, we can see the foothills of Vermont bathed in sunshine. The East is still dark and cold; the West tells the story.

Creation, and dream. Perhaps neither one is possible without the other. I don't know. But no one can sit high in Dartmouth Hall in the late afternoon and not feel the force of the lines:

Who can forget her soft September sunsets?

Who can forget those hours that passed like dreams?

The long cool shadows floating on the campus. The drifting beauty where the twilight streams?

October afternoons I sit at my desk with a typewriter and a bunch of notes - and watch a touch football game. In the hours I have wasted watching these games I could have written a calculus text. I'm glad I didn't. It wouldn't have been a very good book. December mornings I hear the clanging bells, the crunch of feet on snow. In March, feeling like a lifeguard at a swimming beach, I look down at the students crossing on the duckboards. March is a marvellous month, once you have learned to stop fighting it. This is the month of the long white afternoons, the twilight glow.

May would be good if we could only slow down and enjoy her, but we keep hurrying on to that conclusion which we call Commencement. By a stretch of the imagination it is Commencement for the black-robed seniors, but it is Conclusion for every one else: undergraduates, janitors, precinct commissioners. The faculty, after the ordeal of examinations and Commencement, is at peace, but not asleep. There is that monograph that we promised to get to the publisher by August first. Books to read, papers to referee, and that new course we are to give next fall. A pleasant summer; and this year a profitable one. The jobs get done, but before we know it, September with her sharp and misty mornings. The Tanzi Brothers, wise in the ways of the world, say "It won't be long now." And it isn't. This is the high tide of the year. The bells ring, commanding and yet understanding. You start across the campus to your class, curiously thrilled, although this has happened so many times before. You are ready: you know just how you are going to begin: "Gentlemen of the Class of 1961...." After that there will be some wise and witty comments. You want to start off just right; you want this class to be one which your boys will remember; their first class at Dartmouth.

And suddenly, right out in the middle of the campus, something happens. Past and Future do not exist. There is only the Present. A Present with a breath-taking type of newness. This is your first class. You also are beginning at Dartmouth:

Dartmouth! The gleaming, dreaming walls of Dartmouth, Miraculously builded in our hearts.

"I am a blackboard and chalk man ..."

"The situation calls for dynamite"

"I came in a 24-seat year"

"In March, feeling like a lifeguard, I look down at the students ..."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePsychology at Dartmouth

February 1958 By CHARLES LEONARD STONE '17 -

Feature

FeatureFastest Man on Skis

February 1958 By BOB ALLEN '45 -

Feature

FeatureRegional Leaders Named for Campaign

February 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

February 1958 By JOHN A. SAWYER, FRANK T. WESTON -

Article

ArticleThe Murder of Christie Warden

February 1958

Features

-

Feature

FeatureYou Can’t Always Give What You Want

May/June 2004 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

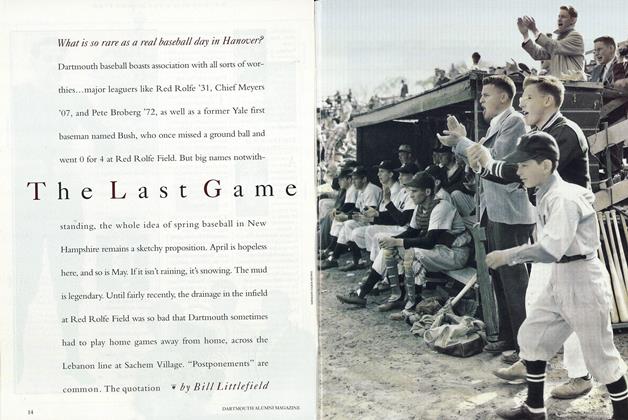

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Last Game

April 1993 By Bill Littlefield -

Feature

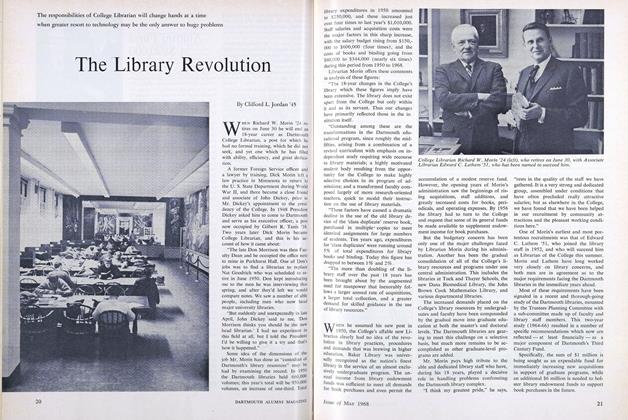

FeatureThe Library Revolution

MAY 1968 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Broadcasters and the Government

February 1960 By ELMER E. SMEAD -

COVER STORY

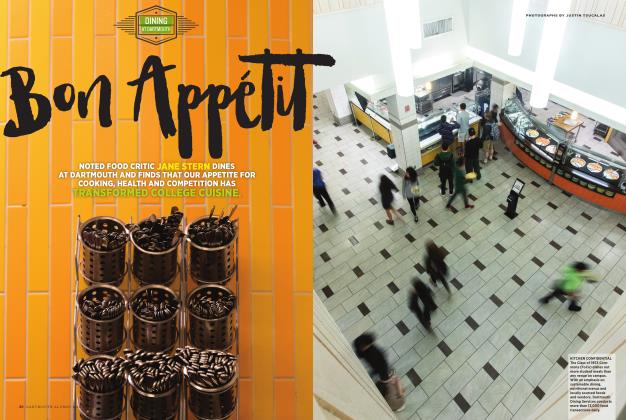

COVER STORYBon Appetit

JULY | AUGUST 2017 By Jane Stern -

Feature

FeatureEducation's Marshall Plan

JULY 1967 By ROBERT H. WINTERS, LL.D.