For five days last December, a corner of the Dartmouth campus was transformed, quietly and without fanfare, into a diplomatic arena in the cause of peace.

The occasion was Dartmouth Conference VII, seventh in a series of unofficial, off-the-record talks among a couple of handfuls of influential shakers, makers, and thinkers from two of the world's superpowers—the United States and the Soviet Union—that began at Dartmouth 13 years ago.

They gathered by design without the usual panoply of publicity and ideological histrionics which so often accompany official conferences and freeze differences. Indeed, except for a scarcely detectable extra flurry of activity around the Hanover Inn and at Hopkins Center's Alumni Hall, one would not have known that anything out of the ordinary was happening.

Yet, for five days, forty leading Soviet and American business executives and managers, scientists, economists, publishers, writers, and politicians talked candidly about how the two nations might improve relations and mutual understanding through increased trade, cooperate in protecting a healthy human environment, and reduce or defuse international tensions.

Results of the dialogue may never be measured. No accords were signed, no protocols initialed. But importantly, very important persons from the two countries—each in position to make or shape in some way critical national decisions and actions affecting Soviet-American relations—had the chance to talk with each other about crucial issues in a nutsand-bolts way that eludes them at formal conferences.

Yet, because of the caliber and influence of the men invited to participate, the conference is recognized as being far more than a debating exercise. Each participant knows that the recommendations growing out of the probings for areas of potential cooperation—and even reports of attitudes—will be fed in various unofficial ways into official channels and seriously considered for possible substantive action.

In a couple of instances, past conferences have set off dramatic chains of events, according to Norman Cousins, editor of World magazine, co-chairman of the American delegation to the conference, and one of the initiators of the series.

He has recalled that, as a direct consequence of discussions during an early Dartmouth conference—held fortuitously at the time of the Cuban missile crisis—he was designated as the intermediary in an unofficial liaison mission among Soviet Premier Nikita Khruschchev, Pope John XXIII, and President Kennedy. That mission resulted in the release of a Catholic bishop long imprisoned in the Soviet Union, elicited from Premier Khruschchev a pledge of greater religous freedom in the Soviet Union, and moved the two nations closer to talks on the reduction of nuclear arms, now still going forward as SALT II.

Similarly, the proposals for increasing Soviet-American trade initiated by President Nixon and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev at the Moscow Summit Meeting last year are recognized as having had their genesis in Dartmouth Conference VI held in Kiev in 1971.

At that meeting, trade possibilities were explored in detail, and participants on both sides agreed that it was past time for the two nations to find ways to regularize and increase trade between them. Despite the size and leadership roles of the two nations in the world, Soviet-American trade remains a small fraction of either country's total.

The Soviet response at the Kiev meeting underlines how sensitive and alert the governments can be to the signals given at these Dartmouth conferences. The sixth session ended at 11 p.m. one day. An hour and a half later, just as the American delegation was boarding a bus to leave Kiev, the four American trade specialists were suddenly called aside and requested to enplane immediately for Moscow. It was explained that Premier Alexsei Kosygin, returning at that same time to the Soviet capital from a trip to Mongolia, would like to talk with them. That afternoon, the American quartet met for about four hours with Kosygin, who at the end asked the delegates to convey to President Nixon his hearty concurrence with the conference recommendations favoring expanded trade. From there, the negotiations passed into the hands of government people, leading to the Moscow Summit.

Now again, one group at Dartmouth Conference VII, chaired by David Rockefeller, chairman of the board of Chase Manhattan Bank, spent four days exploring practical ways and means by which, despite basic economic differences, American and Soviet producers could find and serve markets in each other's country. In effect, they began the arduous task of figuring out how to implement the Nixon-Brezhnev accord on trade, seeking common grounds of understanding in such areas as pricing, credits, and monetary exchange, establishing adequate and reliable flows of information about products, and setting up protection against dumping or other economic disruption.

Although not formally on the agenda, one of the subjects which American participants pressed informally and frequently at the recent conference was this country's grave concern with the virtually confiscatory emigration fee being charged Russian Jews seeking to leave the Soviet Union for Israel.

This expression of concern was reinforced and dramatized by a candlelight protest vigil conducted by several dozen Dartmouth students in the snow outside the Hopkins Center on the second day of the conference.

In part because the protest, as described by Gordon J. F. MacDonald, the Henry Luce Professor of Environmental Studies and Policy and one of two Dartmouth faculty delegates to the conference, was "conducted with great restraint and even beautifully done," the point had been made.

Shortly after the conference, it was reported that the Soviet Union had relaxed its application of the emigration tax—at least for a time—in some kind of signal, and Mr. Cousins specifically called President Kemeny to say he was convinced Moscow was responding to the concerns expressed with eloquent restraint by Hillel members and friends at Dartmouth and by the conference participants.

Significantly, beyond the months of the planning that went into Dartmouth Conference VII by the Charles F. Kettering Foundation, which sponsored it, and Assistant Dean of the College Gregory Prince, Dartmouth undergraduates proved to be the catalysts that gave the recent conference a special quality of spontaneity and candor.

Part of the special hospitality features planned for the Soviet visitors was the enlistment of volunteers from Russian language classes to serve as bi-lingual handymen around the conference, available to drive the Soviet delegates on sightseeing trips or to accompany them to the stores on Main Street. Other students in the Russian Civilization and Culture course of George Kalbouss, Assistant Professor of Russian Languages and Literature and one of three faculty rapporteurs of the conference, also helped.

Thus, right from the start, the undergraduates added an informal and friendly human touch that dented the reserve of the Soviet delegation.

Formalities were further broken down on Monday evening when various members of the Dartmouth faculty involved in the conference in one way or another had small groups of American and Soviet delegates to their homes for dinner.

But the real breakthrough came on Tuesday evening, when the Dartmouth Glee Club presented a special concert for conferees and participating faculty.

Among a medley of foreign songs, the Glee Club sang three Russian numbers, in Russian, with arrangements written by Professor Kalbouss' father, a musician who had left Russia shortly after the November Revolution but who had continued to specialize in playing Russian folk and popular music in this country.

When the Glee Club sang the catchy, rhythmic "Galinka," the feet of the Russian guests could be seen to start tapping and their until then impassive expressions to give way to visible smiles. And when the Glee Club switched its mood to sing the melodic, nostalgic song of "Moscow Nights," a mellow mood settled in and never left.

At the start of the concert, it was'not known how many of the Soviet conferees would attend a reception scheduled by the Glee Club after the concert. But the medley of Russian songs had cast its spell, and almost all came. Later, when by request the singers sang the songs again, the Russians joined in and some of them even started dancing, one persuading Mrs. Kalbouss to join him in a Russian folk dance.

That "'evening the Soviet visitors stayed late talking freely with both students and their American hosts, as they waited up to see on TV the Apollo moon rocket lift off. The next day, breaking all precedent, as far as is known, several expressed an interest in talking to or attending Dartmouth classes.

Evgeni K. Fedorov, a member of the USSR Academy of Sciences, chief of the main directorate of the Soviet Hydrometeorological Service and cochairman with American Russell Train of the American-Soviet environmental survey group, talked to a class of David T. Lindgren, an assistant professor of geography who served as rapporteur for the conference subcommittee on environmental matters. In the course of his talk, he acknowledged that the now extensive nterest among Soviet youth in environmental protection matters was triggered by reports of the vanguard role American youth were taking in persuading American governmental bodies to confront the pollution hazards.

Nikolai Orlov, director of market research at the Soviet Institute of the Ministry of Foreign Trade, and Michael I. Zakhmatov, chief of the economic foreign trade section of the Institute of U. S. Studies of the USSR Academy of Sciences, visited a joint class of graduate students at the Tuck School of Business Administration and the Thayer Engineering School. Their host was Wayne Broehl, Professor of Business Administration, rapporteur of the conference section on trade. Earlier, Tuck School Dean John W. Hennessey Jr. had entertained the Soviet trade specialists at dinner at his home overlooking the Connecticut River.

Yuri A. Zhukov, a deputy to the Supreme Soviet of the' USSR and a political commentator on the Soviet newspaper Pravda, spoke to a class on military history at the invitation of Louis Morton, the Daniel Webster Professor of History, and Jonathan Mirsky, Associate Professor of History and Chinese.

And finally, Boris N. Polevoi, editor-inchief of the magazine Youth and president of the Soviet Peace Fund, spoke to the final session of Professor Kalbouss' class on Russian Civilization and Culture.

The logistics planning that went into making sure the conference ran smoothly presented a gargantuan task to Dean Prince and his aides, and ranged from pretasting the Vichy water the Soviet visitors had indicated they wanted to rigging the complex communications system to provide for simultaneous translation.

Yet it was the myriad of thoughtful little amenities that made the conference an outstanding one from the human point of view.

For instance, Nancy Lindgren, wife of Professor Lindgren and a talented ceramist, fashioned by hand and fired in her own kiln 27 stoneware patio lanterns for all the Soviet visitors. Each lantern featured on opposite sides a depiction of Dartmouth Hall, representing the United States and the site of the first and seventh conferences, and St. Basil's Cathedral in Moscow, representing the Soviet Union.

But the amenities did not stop with the making of the lanterns. At the final banquet, they were brought in on a tray, all with lighted candles shining through the window cutouts, and, on signal, each American arose and took a lantern to his Soviet counterpart in what proved to be a moving moment of personalized friendliness. Later, with old world courtliness, several of the Soviet recipients came up individually to thank Mrs. Lindgren and kiss her hand.

in addition, each conferee received a copy of The College on the Hill, the Dartmouth chronicle written by Ralph Nading Hill "39, and each volume contained a special greeting from President Kemeny on the flyleaf.

John Scotford '38, the College designer, created a striking souvenir poster for the conference, showing the Dartmouth Pine, also suggestive of the palm of peace, linking depictions of the American and Soviet flags, with the entire design contained with a circular peace symbol. From this design, Mrs. Kalbouss, who also is the designer of the bicentennial flags of the Church of Christ at Dartmouth College, made a Dartmouth Conference VII flag which hung in Alumni Hall while it served as headquarters for conference plenary sessions.

To make free moments pleasant socially, a hospitality room was set aside for conferees in the Inn, and there Dean Prince installed a teletype terminal to the Kiewit Computation Center. In addition, with a big assist from the Russian Department, he presented each Soviet visitor with a primer on how to use the Dartmouth Time-Sharing System, written in Russian, and a user number. And at least one program was rewritten to produce its printouts in Russian, and in the acrylic alphabet. Needless to say, not only was the computer a great hit, but the Soviet scientists and scholars were fascinated by the way Dartmouth had made the computer an integral part of its educational facilities.

Thus, when the group was invited by President and Mrs. Kemeny to their home, President Kemeny was even able to persuade one of his Soviet guests to take on the computer in a game of chess. Postscript: the computer won, after "breaking up" the Russian with its bumptious comments, such as "How could you make such a silly move?"

A special guest of honor at the final banquet was former President John Sloan Dickey in tribute to his role in making possible the first Dartmouth Conference in 1960.

It all began late in the 1950s when President Eisenhower became convinced it was important to find some way to speed cracking the ice of the Cold War. There was at that time very little effective conversation between the two countries outside of official channels, and those were still frozen in well-set positions of antagonism or suspicion. President Eisenhower's idea was that if highly respected private citizens near the levers of power could be marshaled to discuss mutual problems in a private, off-the-record conference, the governments could then review the proposals and later, without loss of face, arrange official meetings to frame formal agreements.

Norman Cousins was authorized by President Eisenhower to travel to the Soviet Union and propose such a meeting. The first few overtures met with rebuffs but on the fifth or sixth try, the Soviet leadership decided to risk a test session.

Casting about for a site removed from urban distractions and national press, Mr. Cousins went to his old hunting and fishing companion, President Dickey, who, from his years with the State Department, understood both the importance and problems of such an undertaking. He immediately invited the conference to come to Dartmouth and that first session in 1960 was so successful that the pattern has been repeated at irregular intervals six times since.

Although held at different sites alternating between the United States and the Soviet Union, the conference has retained its Dartmouth identification in tribute to the role the College played in making the first round live up to the hopes held out for it as an informal instrument of diplomacy.

The seventh session was the first time it had reconvened at Dartmouth, and, as Professor Kalbouss said describing his students' reaction to the conference presence: "The whole thing was thrilling to be a part of. I think we all were aware that we were participating in an historic event of some sort."

Among key people instrumental in making Dartmouth Conference VII possible were two Dartmouth alumni in leadership positions in the Kettering Foundation, which has sponsored the last several conferences. They are Robert R. Chollar '35, president and chairman of the board of the foundation and American co-chairman of the conference, and Richard D. Lombard '53, vice chairman of the foundation and a Trustee of Dartmouth College. The other Dartmouth participant, in addition to Professor Mac Donald, was Prof. Dennis L. Meadows, director of the Club of Rome study on "The Dilemma of Man" and coauthor of the book Limits to Growth.

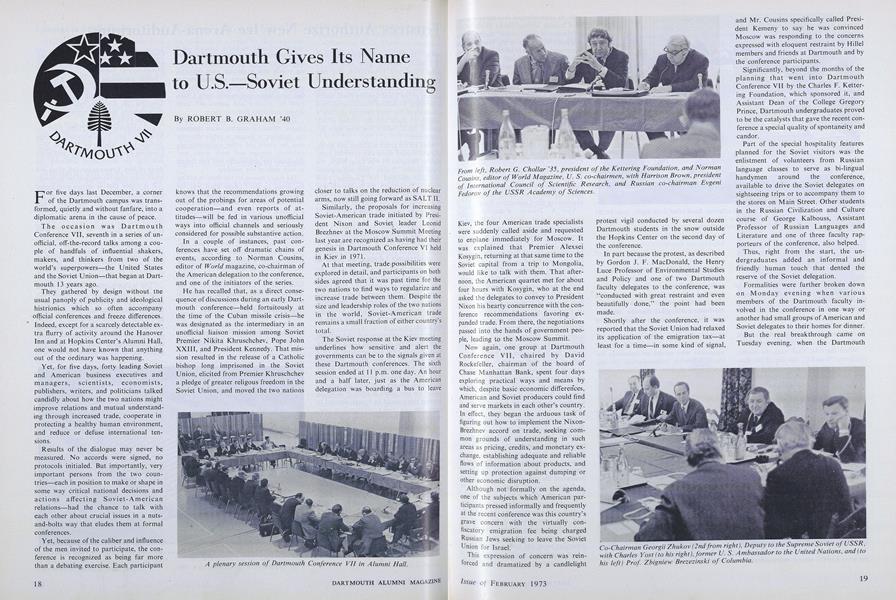

A plenary session of Dartmouth Conference VII in Alumni Hall.

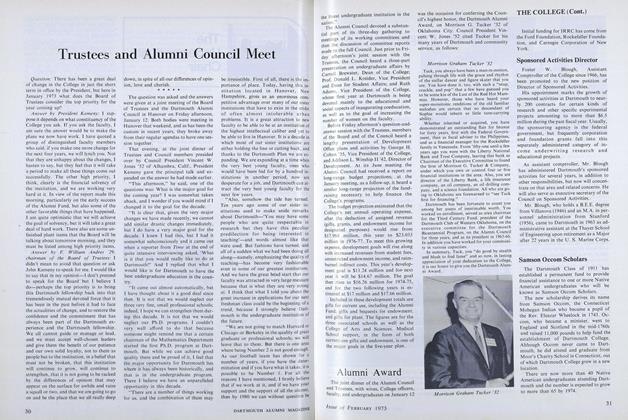

From left, Robert G. Chollar '35, president of the Kettering Foundation, and NormanCousins, editor of World Magazine, U. S. co-chairmen, with Harrison Brown, presidentof International Council of Scientific Research, and Russian co-chairman EvgeniFedorov of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

Co-Chairman Georgii Zhukov (2nd from right). Deputy to the Supreme Soviet of USSR,with Charles Yost (to his right), former U. S. Ambassador to the United Nations, and (tohis left) Prof. Zbigniew Brezezinski of Columbia.

David Rockefeller, chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank (2nd from right), was U. S.chairman for the sessions on trade. To his left is Nikolai Orlov, Director of MarketResearch. Institute of the Ministry of Foreign Trade.

Ceramic patio lanterns, made by NancyLindgren, faculty wife, were presented toall the Soviet delegates.

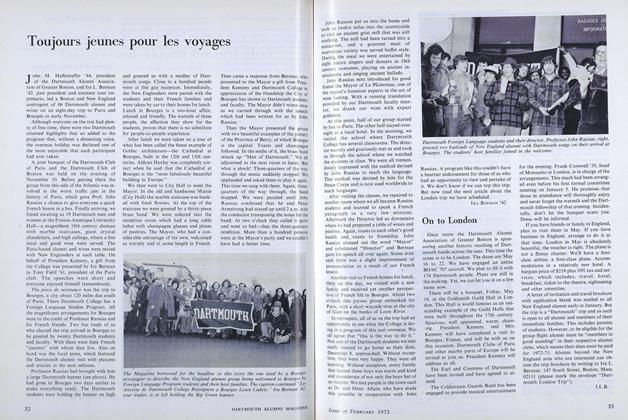

Boris Polevoi, editor of Youth magazineand president of the Soviet Peace Fund(with interpreter), speaking to a class onRussian civilization.

Yuri Zhukov, political commentator for Pravda, meeting with military history classtaught by Profs. Louis Morton and Jonathan Mirsky.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

February 1973 -

Feature

FeatureThe Making of a Mural

February 1973 By GOBIN STAIR '33 -

Feature

FeatureToujours jeunes pour les voyages

February 1973 By IRA BERMAN '42 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Alumni College

February 1973 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

February 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Days—60 Years Ago

February 1973 By Leslie W. Leavitt '16

ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

-

Feature

FeatureNew Environmental Studies Program To Be Launched in the Fall

JUNE 1970 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Price Clean Air?

JUNE 1971 By Robert B. Graham '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

OCTOBER 1971 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

DECEMBER 1971 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

MARCH 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Story, A Narrative History Of The College Buildings, Peioke, and Legebds

June 1992 By Robert B. Graham '40

Features

-

Feature

FeatureConvocation Installs Tucker Foundation

DECEMBER 1958 -

Feature

FeatureFood for Alumni Thought

DECEMBER 1967 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement '88

June • 1988 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH and DARTMOUTH

DECEMBER 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN, JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureReels, Jigs, and Hornpipes

April 1974 By THOMAS W. SHERRY