By Foster ErwinGuyer '06. New York: Bookman Associates,1957. 247PP. $4.00.

By the time Chretien de Troyes appeared on the scene of medieval French literature in the last half of the twelfth century, the reading public — or rather the listening public which gathered around as the traveling minstrel sang his tales of the knights of old - was beginning to grow tired of the heroes of the epic poems, of which the Song of Roland was the best known. These epic figures were actually very tough characters: they treated their women almost as roughly as they did their enemies; most of their waking hours were filled with the sound of battle: bloody, brutal, and always victorious.

When the public was ready, Chretien appeared with a completely new style, the romance. Its success was enormous: here were chivalrous knights who adored their ladies, who had time for the leisurely pursuit, who even talked a gentler and far more poetic language. Chretien de Troyes did not invent the romance all by himself; the work of his predecessors and contemporaries has been studied by the late Professor Guyer in his Romance in the Making, published in 1954. But Chretien's romances were superior to all others and his influence has been unequalled.

Professor Guyer, whose death last November saddened the Dartmouth community, tells us just how widespread this influence has been in Italy, Spain, France, and England. The volume is an able presentation of the patent rights which Chretien might claim in the modern novel. In the early chapters, Professor Guyer analyzes the various works which Chretien wrote. He then traces Chretien's influence upon such novelists as these: Chaucer, Shakespeare, Rousseau, Sir Walter Scott, Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Balzac and Tennyson.

Did Chretien de Troyes actually invent the novel? There may be some who will dispute his claims. Nevertheless, there are few elements in the modern novel that were not also present in Chretien's romance. It may perhaps be significant that the French continue to use the word roman for our "novel." In any case, Professor Guyer's volume will serve as a useful introduction to Chretien de Troyes. It will also serve as a reminder to the novelist of the twentieth century of the debt which he owes to this "inventor" of the twelfth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe State of Our Purposes ... and Vice Versa

March 1958 -

Feature

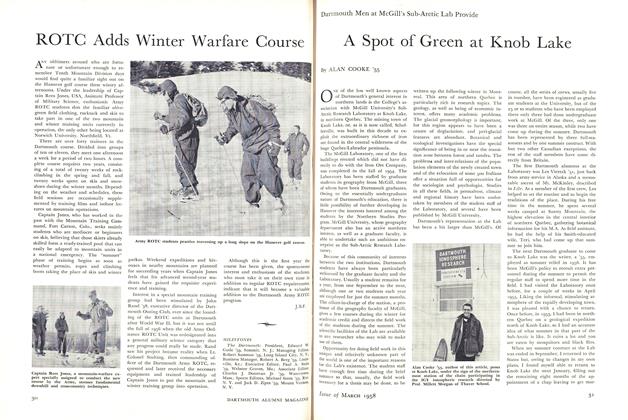

FeatureA Spot of Green at Knob Lake

March 1958 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Feature

FeatureA BIG NIGHT AT THE WALDORF

March 1958 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Has Record Attendance

March 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

March 1958 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, WALLACE BLAKEY, JOHN F. RICH

WILLIAM R. LANSBERG '38

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

February 1935 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

JUNE 1971 -

Books

BooksA PRIVATE PARTY.

March 1954 By HENRY M. DARGAN -

Books

BooksYACHTING IN NORTH AMERICA.

March 1949 By Herbert F. West '22. -

Books

BooksYANKEE KINGDOM.

July 1960 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksGOVERNMENT, BUSINESS AND VALUES,

October 1943 By WILLIAM A. Carter '20