PRESIDENT DICKEY'S ADDRESS AT THE HOPKINS DINNER

THIS occasion has been billed as the greatest Dartmouth gathering ever held outside Hanover. Having a decent regard for certain remarkable Saturday afternoon gatherings that have been held outside Hanover, we might clinch tonight's claim to unique fame simply by adding the qualifying word "indoors" or, if we would be both more exact and more embracing, we can surely claim tonight to be the greatest Dartmouth black-tie gathering ever held anywhere.

However we may prefer to have the superlative qualities of this occasion defined, there can be no doubt that it takes its unique distinction from one whose service in Dartmouth's purpose makes him both the most honored and most beloved among all the men of Dartmouth.

It is fitting on such an occasion that the privilege of bearing our formal sentiments of tribute should fall to a New Hampshireman whose bearing of himself in the public service is one of the brightest chapters in the long story of Dartmouth. And it is no less fitting that the sentiment of this very special Dartmouth night should be personified in the lifelong Dartmouth devotion of our chairman who first learned of our honored guest as a young boy through the admiring eyes of his own distinguished father and Dartmouth's good friend, John D. Rockefeller Jr. It is my privilege on behalf of all of us to thank Governor Adams and Nelson Rockefeller not merely for their parts here tonight but beyond tonight for lives and careers which have added to the definition of Dartmouth's distinction.

My part in tonight's affair pays its portion of tribute to you, Dr. Hopkins, in the form of a report from the front on how goes the fight for liberal learning which you, as the eleventh in the Wheelock Succession, so gallantly led forward in a campaign of nigh thirty years' duration.

With postal-card terseness our report could be put thus:

"The fight continues. The forces of ignorance are being pushed back but they never retreat; their reinforcements seemingly are endless, their territory seems unlimited and their resourcefulness in resistance defies description. When we win everybody wonders; when they win nobody wonders. We need more men, better weapons and more money - lots of it. We are of good heart but wish you were here. Love."

The military figure of speech makes a point but we can also simply say straight-forwardly that any education worth having has always been and always will be hard work. Whatever else we can do with pills and push buttons, we have no prospect of bringing men to knowledge, ma- turity and wisdom with such devices. Education has become big business but learning is still ultimately, both painfully and joyfully, a one-man enterprise.

One hesitates to speak of such elementary things on this occasion and yet if we are to understand the crisis scene in American education on which the curtain has just gone up, I am sure we must be willing to begin at the beginning.

Where does education begin? I propose to you that it begins for both the individual and the institution with those powerful words Dr. Hopkins used to entitle his collected papers - "This Our Purpose." Purpose is the front on which the fight for liberal learning is always won or lost. If our purposes are wrong, nothing else can be really right, but if our purposes are right, we have the great advantage of knowing where we want to go, however hard the going may be from one day to the next.

In a totalitarian society, to borrow the Biblical idiom, in the beginning there was the state. In such a society a man's purposes are supposed to be what the government wants. What the government wants may come packaged in a fancy ideology or it may come simply in a blunt, unexplained command. Regardless of how it comes, the daily goal of human activity is not something millions of individuals have to work out for themselves man by man, family by family, group by group, or institution by institution. In such a society your purposes come ready-made.

Is there any doubt on the other hand about where the beginning is as to anything in a free society? It is plumb inside the personal purposes of each one of us.

I PROPOSE tonight to say bluntly that on the whole our personal purposes are not good enough to produce the kind of education we say today we must have. Personal purposes are largely learned and my guess is that they are learned earlier and more by example than most of us as parents care to believe. This is the point where each one of us must himself write part of the answer as to what's wrong with American education. How many of us, honest Injun, can say that either the home from which he came or the home he in turn created, let alone the homes of his friends, would get high marks as places where the life of the mind was honored in word and deed? Could we give a different answer as to our clubs, our businesses, the average American alumni association?

Yes, we all had good homes and there are many other fine things in life besides the human intellect, but that's not the point, is it? At least that's certainly not the point if we're in earnest about why the American schoolboy and college student is often not intellectually motivated and intellectually creative.

It is simply neither fair nor good sense for you and me to expect entire student bodies to be propelled, so to speak, into the outer space of the mind by the pur- poses of any number of good teachers. In this kind of space travel you've got to rely on the thrust of your own rockets and you've got to go yourself, not send a dog.

Good teachers, especially the rare great ones, are in perilously short supply. We can and we will do something about our teacher shortage through that old-fashioned remedy that goes back to the Phoenicians, namely, money; and we can also insist that all of us, including the teacher, try to be more resourceful in finding better, more effective ways for spreading the influence of good teaching over more students rather than just more students over a good teacher. The possibilities for progress on this problem through a combination of more old-fashioned money and a few new ideas are undoubtedly very real and very substantial.

The equation between good teaching and good learning is not fixed. The relation shifts as the student grows. At first good teaching is the preponderant thing, but if it's education we're talking about, at some point, and the sooner the better, good learning must become the ever larger part.

The point I want to make here is that in education, especially at the higher levels, there is nothing, literally nothing, that could so quickly raise and compound both the quantitative and the qualitative productivity of our existing fine teaching force as a more intellectually motivated American student. A hungry student does the same thing for a teacher that a fighting soldier does for a general - wins the battle and makes the general look good and feel even better.

I suggest to you and to myself that here is a sector of the educational front where you and I who probably never again will raise the intellectual level of the nation by our efforts as students can come hand-to-hand to grips with the problem, begin to do something about it right here tonight, now, and, believe it or not, without acting like a taxpayer. Whatever else is beyond us, it is within the reach of each of us to upgrade the life of the mind in our daily attitudes. Nothing, literally nothing, will produce a quicker or more lasting renaissance in American education than such an improvement in our personal purposes.

GOVERNMENT has its part to play in the total effort needed to achieve a true national breakthrough on the educational front, but, as with any deep human trouble, the remedy for deficiencies in personal purpose are not for sale in Washington or anywhere else. This kind of repair work must be done inside each of us on our lonely own.

The Federal Government does have purposes of its own that touch both the purse and the purposes of American education. Let me give several illustrations HI higher education where what needs doing can only be done in Washington.

First, take the basic problem of solvency for both our colleges and their customer - the average parent who pays as his children go. There are not many good devices for getting the Federal Government into this problem without getting it into education more deeply than many of us want. There is, however, one clear way that is now before the Congress with the support of most of the major educational groups and that is to amend the income tax laws so as to permit any parent to take a tax credit against what he pays in tuition to any college, public or private. Such legislation would permit all institutions both to increase their own scholarship coverage and, by charging more realistic fees for those who can and ought to pay their way, to raise their teachers' salaries.

An even more direct instance is at hand. The Federal Government right now is operating educational programs of its own involving over a quarter of a million college students on the campuses of some three hundred public and private institutions from coast to coast. I refer to the ROTC programs of the Army, Navy and Air Force. There cannot be the slightest question about the propriety or the necessity of this highest of all Federal purposes, our national defense. These programs no longer merely produce reserve officers to be called up in time of emergency, they are now a principal source of supply for active duty officers as well, actually producing more regulars than the service academies. Contrary to the impression of most people, the colleges receive no direct financial assistance from the Federal Government for these programs.

I am one who believes that under present conditions a broadly conceived and adequately financed ROTC program would be good for the nation, the colleges and many of our students. I do seriously question whether the existing three separate programs are thus aligned to the critical educational needs of our national security today. I believe the time is here for a totally fresh, first-rate study of this educational purpose and potential from the point of view of both the Federal Government as a whole and of the colleges.

With the financial assistance of the Carnegie Corporation, we are now mounting such a study at Dartmouth. A creative, open-minded approach to this matter could lift ROTC to a position of first magnitude as an educational response to governmental needs. Such a program would surely command the kind of Federal financial support it merited and our colleges require for service rendered.

I shall not undertake a detailed discussion tonight of the various proposals currently being considered for large Federal scholarship programs. I do find it hard to begin "way out there" in the forest when here in the front yard this kind of wood is down and waiting for attention.

I will also say that I seriously doubt whether we have at hand either the teachers or facilities in our high schools and colleges to make the best use of a large, Federal, science-slanted scholarship program at this time. As of now I should prefer to bet my Federal taxes on the compounding benefits that would come from assisting the schools and the colleges to get badly needed instructional facilities and among them, laboratories - without mortgaging community or alumni resources for such requirements. These resources might better be reserved for supporting teacher salaries and other needs the Federal Government cannot reach.

ASSUMING the pluralistic premises of a free society, the educational crisis of this hour is not primarily one of faulty purpose in our institutions or the system itself. We do, of course, have problems of purpose in the American educational system. At some points there is still a division of opinion as to whether we need better minds or better temperaments, but even here the gap of disagreement is narrowing as both sides gradually concede that neither a well-adjusted blockhead nor a maladjusted egghead is necessarily just what the doctor ought to have ordered, whether he be a doctor of pedagogy or of philosophy.

American higher education also has its institutional disagreements about purpose and emphasis. There is not complete agreement about the comparative value of cultural and vocational studies, but here again we've found a lot more common ground than existed a few years back when seemingly endless battles were being waged by purely platonic suitors over whether the Mona Lisa or the monkey wrench was most to be loved.

The large truth is that America is pluralistic in educational purpose as in religion, economics, politics and almost all else. No thoughtful person doubts for a moment that this diversity of purpose can put our country at some disadvantage, at a given moment, as to certain things, in competition with a totalitarian state such as the Soviet Union where all purpose is monolithic.

This fact presents us today with a frightful question of judgment: is this competitive disadvantage so perilous that we have no prospect of surviving unless we too focus our educational diversities into a sharp instrument of military preparation? I frankly am not sure what my attitude would be if I believed the answer to that question had to be "yes." I am inclined to guess that most Americans even in the terrible tension of cold war will never give a flat "yes" answer to that question simply because as a free society we are constitutionally incapable of believing that suicide may be the best policy after all.

To be exterminated by someone with inferior purposes but superior weapons is certainly neither a desirable nor noble end, let alone a promising prospect for liberal learning. Let us be clear, such an outcome is not necessary. But let us also be clear that if the best of American education now panics and loses its sense of great purposes, American power will assuredly lead, as Soviet power today leads, to what great power without moral restraint has always led - a very dead end.

As for the great purposes of Dartmouth, I stand where staunch predecessors stood, on the belief that the ultimate obligation of the College is to human society and that this obligation is best met by a liberating education that enlarges a man's will and capacity for the creative enjoyment of life. I believe further that the creative enjoyment of life in any community of men and in any employment requires a lifelong cultivation of both competence and conscience in the same man.

Finally, I believe that in college, as in an adult life, these things are best learned together and that in the pursuit of competence and conscience most men will find it helpful to know the clues left behind by those creative men and women to whom you and I owe the liberation into which we were born.

We call these clues the liberating arts because it is through knowing and use of them that men are liberated from the meagerness and meanness of mere existence. These civilizing trail marks are found wherever a truly creative mind has ventured - in all the sciences, in all the arts and in all the beliefs by which we live and prepare to die. If ever there was a time when any man could theoretically master all the knowledge of his civilization (and I doubt that such a paragon of scholarship ever actually existed), that time is many, many old-fashioned moons behind us.

The great interdependence of today and tomorrow is neither political nor economic. It is the absolute and ever-widening dependence of civilized men on each other for the daily re-creation of the knowledge their civilization breathes. Even though no man can be an island of civilized knowledge "entire unto himself," each of us can be aware that such knowledge exists, we can know something of the whereof and the how of its fashioning, we can each create an informed appreciation of its place in our life, we can man by man work at mastering a small sector of it in return for our daily bread, and finally we can know that out of such a society a few venturesome ones will fashion the clues that lead into tomorrow.

I ask you, is this not the educational creed upon which mind by mind, generation by generation, man's relationship to the universe has grown from a mere quiver of meaningless life to this precious imperfection we call civilization?

If our answer is "Yes, it must have been something like that," then, whatever the crisis, there can be no future in turning our back upon such a sense of purpose. Rather, having cleared our head about this, let us work to focus this purpose into the sharper image of a better performance.

PERFORMANCE in human affairs is hard to judge in an absolute way. There are no records against which to measure yourself in the first race run over any obstacle course. In such a race you judge yourself against the performance of your competition and when you find yourself becoming an authority on the rear view of your opponent, it's time to get going yourself. For the past four months we have been exposed, as the saying goes, to a southern exposure of Soviet science going north and we have judged, rightly I am sure, that this reversal of our normal outlook was not accomplished with mirrors. If we're serious about this one, we'll stop talking a good race and get going.

I speak figuratively but assuredly not frivolously about this challenge to our nation's performance. Inevitably there is frantic talk and silly advice in any crisis, but anyone who has worked close to this one knows full well that there are also many reasons for rational concern. We cannot go far into them tonight. We can say this, whether we regard the problem of war as one to be met by mutual deterrence or enforced disarmament, it is not a happy thing to find both yourself and the sheriff more deterred than deterring.

We can also say that however much ground we retake in the missiles race, and I suspect we still have it in us to put on quite a spurt, the great failure in the performance of all education at this point is in mankind's feeble moral and political response to the problem of modern power. In this race there is no national competitor to spur us on; we are running against ourselves and against time.

If I may be permitted one unqualified certainty tonight, it is that only disaster can come out of any attempt to conquer and control outer space for national purposes. Any such universal arrogance must surely bring down on all of us commensurate catastrophe. President Eisenhower requires the dedicated service of every educated man on earth behind his wise proposals to forestall this ultimate folly. If we can stop this by the positive cooperation of all peoples on this earth, then all else is possible.

It has always been hard for men to act resolutely on things of great urgency and yet know, really know, that other things are of greater importance. But is that not the dilemma of this hour? We have little choice but to compete in the arms race on its own imperative terms, while each day's greater effort tells thoughtful men it is a race that can never be won. Our best hope is only not to lose it.

Keeping us from losing this race of mutual deterrence is a task that American education cannot and will not shirk, but beyond this urgency still stand the great civilizing purposes of all education. Even today, indeed, I say especially today, these purposes are not remote, they are not postponable and they must be well served. If we are asked why, my answer is that only thus can men be grown who will someday be tall enough to win the arms race the only way it can ever be won, by ending it. We cannot know how far off this day may be; we can only know that bringing it nearer remains the prime civilizing business of liberal learning today.

Manifestly, you and I cannot write out a prescription for these tasks on the back of a Waldorf menu. From here on out they are the daily fare of American life.

WE are met tonight in tribute to a man who I believe did more than any other of the great leaders of liberal learning to create as between a college and its product a sense of lifelong partnership. To you, Dr. Hopkins, the men of Dartmouth offer the tribute of being willing to be worthy of the purposes you so nobly served.

We are citizens of many communities and we expect to act as such.

We are the stuff of an institution and we know that what we are, it will be.

Our business everywhere is learning and that forever will be up to us.

We thank you, sir, for being with us all the way, and Good Luck!

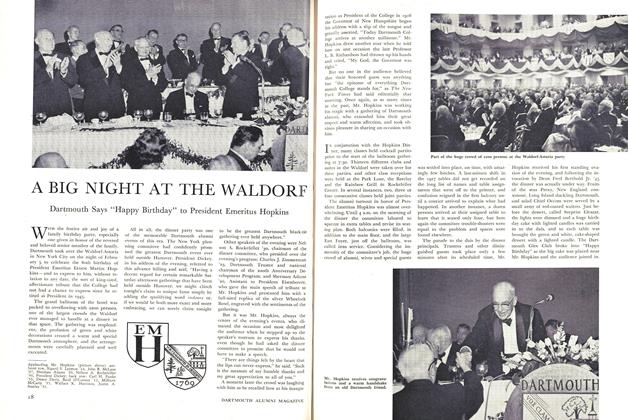

President Dickey speaking at the dinner for Mr. Hopkins, shown at left

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Spot of Green at Knob Lake

March 1958 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Feature

FeatureA BIG NIGHT AT THE WALDORF

March 1958 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Has Record Attendance

March 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

March 1958 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, WALLACE BLAKEY, JOHN F. RICH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

March 1958 By JOHN A. SAWYER, FRANK T. WESTON

Features

-

Feature

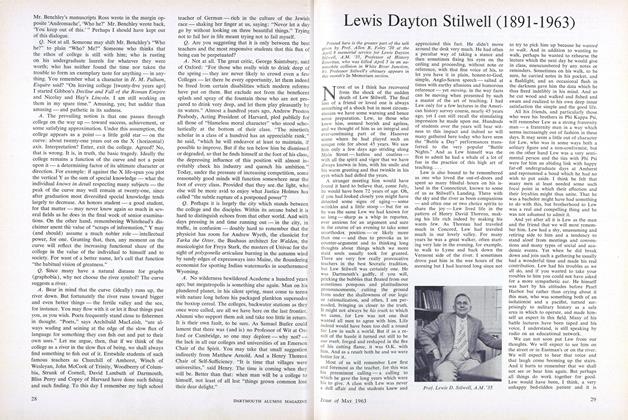

FeatureLewis Dayton Stilwell (1891-1963)

MAY 1963 -

Feature

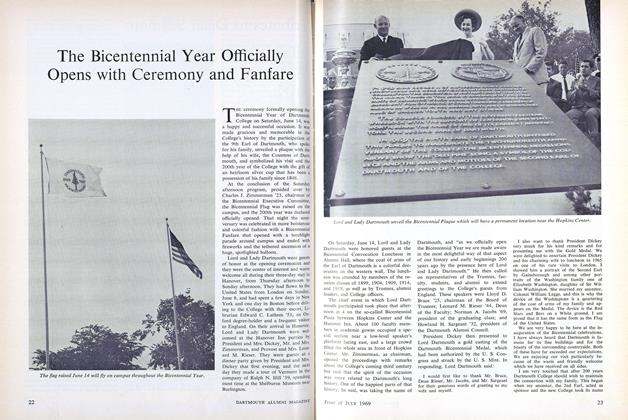

FeatureThe Bicentennial Year Officially Opens with Ceremony and Fanfare

JULY 1969 -

Feature

FeatureA Mother's Dilemma

Jan/Feb 2002 By JAMIE HELLER '89 -

Feature

FeaturePort Professional

October 1973 By M.B.R. -

Feature

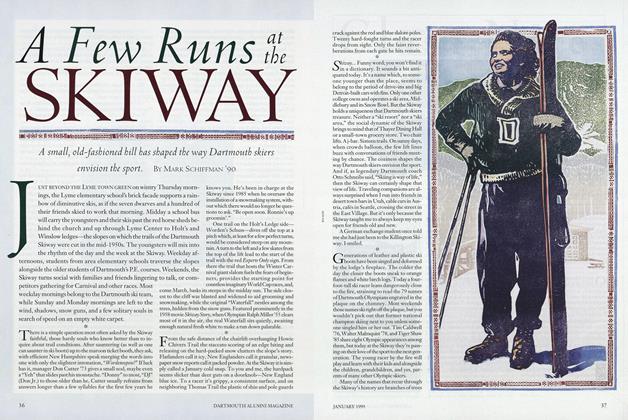

FeatureA Few Runs at the Skiway

JANUARY 1999 By Mark Schiffman '90 -

Cover Story

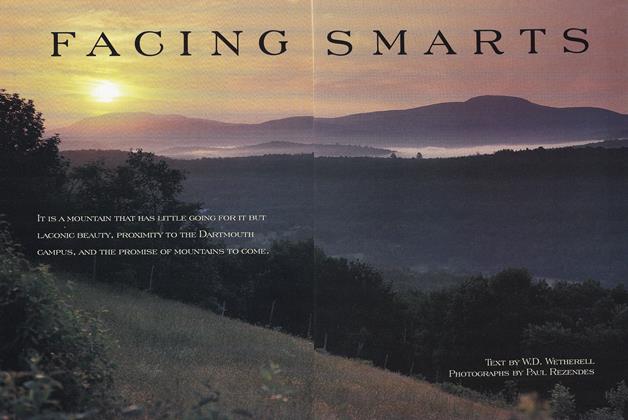

Cover StoryFACING SMARTS

Novembr 1995 By W.D.Wetherell