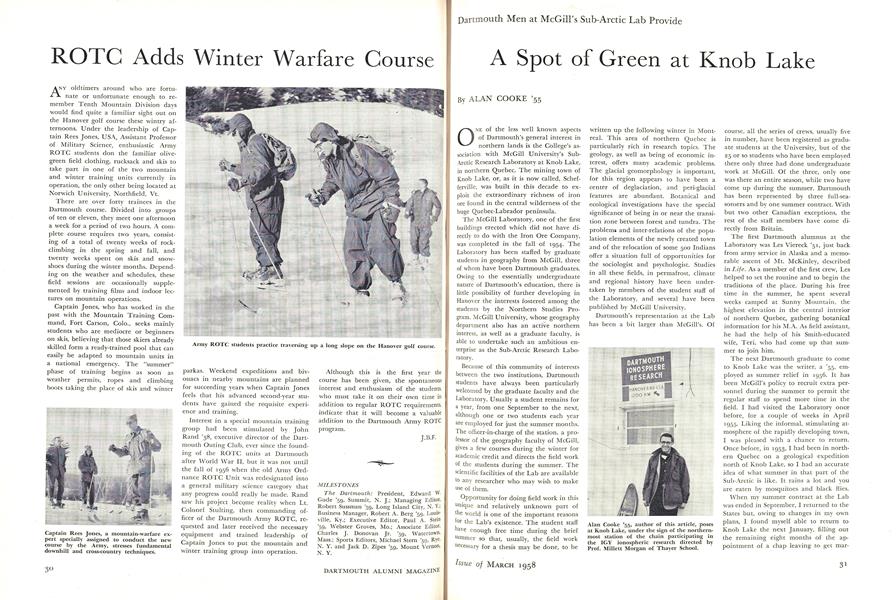

Dartmouth Men at McGill's Sub-Arctic Lab Provide

ONE of the less well known aspects of Dartmouth's general interest in northern lands is the College's association with McGill University's SubArctic Research Laboratory at Knob Lake, in northern Quebec. The mining town of Knob Lake, or, as it is now called, Schef-ferville, was built in this decade to exploit the extraordinary richness of iron ore found in the central wilderness of the huge Quebec-Labrador peninsula.

The McGill Laboratory, one of the first buildings erected which did not have directly to do with the Iron Ore Company, was completed in the fall of 1954. The Laboratory has been staffed by graduate students in geography from McGill, three of whom have been Dartmouth graduates. Owing to the essentially undergraduate nature of Dartmouth's education, there is little possibility of further developing in Hanover the interests fostered among the students by the Northern Studies Program. McGill University, whose geography department also has an active northern interest, as well as a graduate faculty, is able to undertake such an ambitious enterprise as the Sub-Arctic Research Laboratory.

Because of this community of interests between the two institutions, Dartmouth students have always been particularly welcomed by the graduate faculty and the Laboratory. Usually a student remains for a year, from one September to the next, although one or two students each year are employed for just the summer months. The officer-in-charge of the station, a professor of the geography faculty of McGill, gives a few courses during the winter for academic credit and directs the field work of the students during the summer. The scientific facilities of the Lab are available to any researcher who may wish to make use of them.

Opportunity for doing field work in this unique and relatively unknown part of the world is one of the important reasons for the Lab's existence. The student staff have enough free time during the brief summer so that, usually, the field work necessary for a thesis may be done, to be written up the following winter in Montreal. This area of northern Quebec is particularly rich in research topics. The geology, as well as being of economic interest, offers many academic problems. The glacial geomorphology is important, for this region appears to have been a center of deglaciation, and peri-glacial features are abundant. Botanical and ecological investigations have the special significance of being in or near the transition zone between forest and tundra. The problems and inter-relations of the population elements of the newly created town and of the relocation of some 500 Indians offer a situation full of opportunities for the sociologist and psychologist. Studies in all these fields, in permafrost, climate and regional history have been undertaken by members of the student staff of the Laboratory, and several have been published by McGill University.

Dartmouth's representation at the Lab has been a bit larger than McGill's. Of course, all the series of crews, usually five in number, have been registered as graduate students at the University, but of the 25 or so students who have been employed there only three had done undergraduate work at McGill. Of the three, only one was there an entire season, while two have come up during the summer. Dartmouth has been represented by three full-sea-sonsers and by one summer contract. With but two other Canadian exceptions, the rest of the staff members have come directly from Britain.

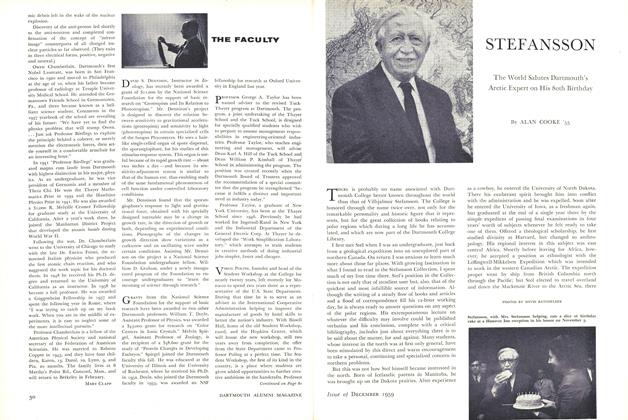

The first Dartmouth alumnus at the Laboratory was Les Viereck '51, just back from army service in Alaska and a memorable ascent of Mt. McKinley, described in Life. As a member of the first crew, Les helped to set the routine and to begin the traditions of the place. During his free time in the summer, he spent several weeks camped at Sunny Mountain, the highest elevation in the central interior of northern Quebec, gathering botanical information for his MA. As field assistant, he had the help of his Smith-educated wife, Teri, who had come up that summer to join him.

The next Dartmouth graduate to come to Knob Lake was the writer, a '55, employed as summer relief in 1956. It has been McGill's policy to recruit extra personnel during the summer to permit the regular staff to spend more time in the field. I had visited the Laboratory once before, for a couple of weeks in April 1955. Liking the informal, stimulating atmosphere of the rapidly developing town, I was pleased with a chance to return. Once before, in 1953, I had been in northern Quebec on a geological expedition north of Knob Lake, so I had an accurate idea of what summer in that part of the Sub-Arctic is like. It rains a lot and you are eaten by mosquitoes and black flies.

When my summer contract at the Lab was ended in September, I returned to the States but, owing to changes in my own plans, I found myself able to return to Knob Lake the next January, filling out the remaining eight months of the appointment of a chap leaving to get married. The reader will note that I have counted myself twice in figuring Dartmouth's representation at the Laboratory. This is not because of a split personality, but because I was there at two different periods, on separate contracts. Continuing the Dartmouth succession at the present time is Tony Williamson '57. An English major converted to geography, he will take his M.A. in that subject next year at McGill.

Frequent visitors at the Laboratory during the last few years have been Dr. Millett Morgan and Dr. Huntington Curtis of Thayer School. The Lab houses one of the oldest units in their chain of Whistler equipment, now part of a far-flung IGY project. Their gear, as nearly as I understand it, records ionospheric noises called specifically whistlers, tweets and bonks. The timing mechanism of the apparatus looks not unlike a pin-ball machine. Pilots from all over the Eastern Arctic come to "have a look at that there thing in the back room you say is a clock." Tending this precious machinery, and that belonging to another IGY project for Stanford University, is yet another Dartmouth representative, Ervil Bentley of West Canaan, New Hampshire, who is working with the Thayer School professors.

AMONG other contracts for scientific work, the Laboratory serves as a firstorder observing station for the Canadian weather station network. This program of observation has remained the chief part of the Laboratory's work, with a routine of 24 hourly statements of "aviation weather," a more complete "synoptic" report every six hours, and pilot balloon ascents to determine winds in the upper atmosphere four times daily. The other contracts include the maintenance of a seismograph for the Dominion Observatory, snow and ice surveys and two IGY projects, one sponsored by Dartmouth.

The principal job, observing the weather, is not in itself an especially difficult operation. The arctic winter is typically cold and clear for long periods; January 1957 had a mean average temperature of —22° F. The sub-arctic summer weather is almost continually terrible, although it manages to be bad in such a variety of ways that one cannot help being interested in keeping track of what is going on. For the hourly aviation reports we recorded cloud cover, visibility, barometric pressure and the altimeter setting, temperature, dew point, relative humidity, wind direction and velocity, together with remarks on special conditions helpful to a pilot. The four synoptics are more complete, including the past precipitation, maximum and minimum tempera- tures, and the barometric tendency. Reports were sent out on an enthusiastically noisy teletype, when it worked, and we received on it other reports from all of eastern North America.

In our capacity as Dominion weather observers, we were a public service to aviators and to the townspeople. Before seeing much of bush pilots, I had supposed them to be exceptionally qualified representatives of their occupation. In actual fact, with lamentably few exceptions, the dozens of them we met bordered on incompetence. Most annoying in them was a superstition that we had some occult control over the weather, that if We said the fog would lift or the rain would stop, it would; that it was pure meanness on our part when we would not venture to pronounce. Forecasting is only to state the probability of weather conditions based on the (generally inadequate) in. formation at hand, but of this concept we could never fully persuade them. Naturally, these gentry got into trouble with monotonous regularity; the wonder being that more were not killed. The townspeople, though not incompetent, contrived to be an even greater nuisance. Apparently the Laboratory possessed the only clock in town in which anyone placed faith, for we were continuously pestered with phone calls, sometimes four in five minutes, to learn the time. This was rather trying when rushing to teletype a report in proper sequence; at such time I usually left the phone off its cradle.

Both times I have lived at the Laboratory it has been a notable experience in Anglo-American relations. As my own family is English, I had begun my sojourn among them with a vaguely pro-British feeling. This by degrees changed, blossoming into a prejudice against attitudes British. Happily, I liked personally the fifteen or so Britons I met there and got to know rather well, but I found it a revealing situation in many ways. Constituting the smallest of minorities (no other American or Canadian was there most of the time), alone in an unfamiliar cultural climate, I was brought to share in a range of social problems I had not before suspected. Forcibly exposed, for a lengthy and confined period, to ideas and attitudes which were not mine, I was obliged to overhaul a good many of my own ideas I had not previously questioned. Generalizing, I concluded that, though remarkably polite, the British are (quite unconsciously) thoroughly intolerant of everything non-British, equating every aspect of civilization with the adjective "British." Their reaction to me, if I understood them right, was that I seemed distressingly American, having no proper respect for the subtle refinements that make a man a gentleman. Perhaps they are right. We remain good friends.

Our private work was more interesting than the routine chores and a good deal more fun. During the winter about all we could do was read and argue, though the Dartmouth contingent has kept up a tradition of cross-country skiing. To get around the gravel roads we were handsomely enough provided with two jeeps and a snowmobile. The sensible thing to have done with them was to drop lighted matches into the gas tanks. The snowmobile never worked. The jeeps, usually, were either in the garage with an expensive and complicated ailment or some ten to fifteen miles out of town waiting to be towed back. On the rare summer days when a jeep was relatively mobile and when the showers stopped for a time, we made excursions into the surrounding territory and, leaving the jeep, went for long hikes. Rough, narrow roads stretched in all directions.

Before the miners and newly settled Indians had shot most of the caribou, we could usually see a few along the windswept ridges. Fox and ptarmigan are common and sometimes a black bear is met. There is a great beauty in the rolling panorama to be seen from the elevations. A few colors fuse in subtle combination: dark green spruce, yellow-green larch and occasional paper birch on fair days lift into the perfect clarity of a northern blue sky, blend back into soft browns and blacks of distant rock outcrops and to the yellowish white of the woodland's lichencovered floor. Patches of burned forest stretch in silver swaths to the horizon. Autumn is most wonderful, for the dwarf willows and birches turn yellow, blueberries and other low plants sweep the open slopes in purple-brown, the far ridges melt into earthy colors and, again, the lichen mat is like new snow beneath the eternally green-black spruce. The blending, shadowing and reworking of this limited range of subdued hues is an unending satisfaction to the eye. Our New England hills in fall are a blazing, dramatic triumph of extravagant color. Though my eyes were brought up to such autumnal flamboyance, I have learned to prefer the controlled richness, the infinite-in-little of the untouched, almost unknown northern forests and tundra.

ONLY newcomers to the town call it Schefferville, although that is now its proper political name. It is more often called Knob Lake, as it was known in the first days of settlement. It has a fluctuating population of about 2500, producing some twelve million tons of high-grade iron ore in a year. The building of a townsite, where many of the miners live with their families, is now almost completed. Knob Lake is strategically important as the distribution point of air supply for mining activities throughout the peninsula, as a center of communication for the Mid-Canada radar line, and as the proposed site for a new jet base. The McGill students at the Lab are fed through the cooperation of the RCAF by their messing facilities. Earlier Lab crews had to do their own cooking, a problem which was often resolved by five separately prepared, separately eaten meals. During part of my time there, interested by Stefansson's book Not by Bread Alone, I adhered to his well-known meat-and-fat diet. I agree with Stef that this all-meat diet is at once more satisfying and results in greater physical well-being than the usual diet of varied foods.

The town has by now lost almost all the hearty pioneering spirit of its early days and, except for the long winter and moist summer, anyone living there might easily suppose himself in some modern housing development far to the south. The "club" alone retains something of its former primitive flavor of rough simplicity. Aspiring to tavern status under the modest title of "The Quebec-Labrador Pioneers' Association," it is in reality a large-scale log cabin on the edge of town. Beer by the imperial quart is purveyed to members who represent nearly the whole male population. It is possible to bring lady guests, though uncommonly done, for the atmosphere verges from boisterous to unrefined. When the bar closes at midnight, the foresightedly thirsty have their tabletops almost obscured with bottles of the potent brews which I believe are greatly superior to American beers.

The transition from tents and log cabins to modern pastel-colored duplexes has been rapid. There are three churches, including a massively ugly cathedral, a movie theatre, two large department stores, a bowling alley, two schools, a bank and a post office and, just opened, a licensed hotel. Soon this town, too, will receive telecasts and its inhabitants will need no longer to distract themselves with only the best fishing in the world and several hundred thousand square miles of virgin wilderness.

A year in the Laboratory at Knob Lake is a rewarding, fascinating experience. Besides quantities of kodachrome slides, one comes away with a new facet to his education, the memories and lessons of an unusual social situation, a heightened appreciation of the variety and beauty in nature and landscape, and a more adequate understanding of the enormous difficulties inherent in northern planning and development. Unless there may come a time when Dartmouth will be in a position to establish her own arctic and subarctic field stations, we cannot do better than to promote the already excellent relations between Dartmouth and McGill, to the continuing benefit of the students and the two colleges.

Alan Cooke '55, author of this article, poses at Knob Lake, under the sign of the northernmost station of the chain participating in the IGY ionospheric research directed by Prof. Millett Morgan of Thayer School.

Les Viereck '51 and his wife Teri, with Kobuk, shown at Knob Lake on Christmas Day, 1954. Viereck was a member of the first crew at McGill's sub-arctic laboratory.

Tony Williamson '57, an English major converted to geography, is boring a hole in the lake ice to take a temperature reading.

Prof. Huntington W. Curtis of Dartmouth's Thayer School working on an antenna used in the research project recording whistlers and other noises of the ionosphere.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

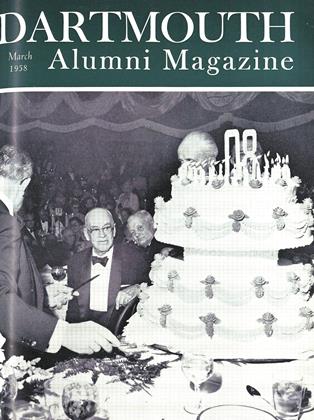

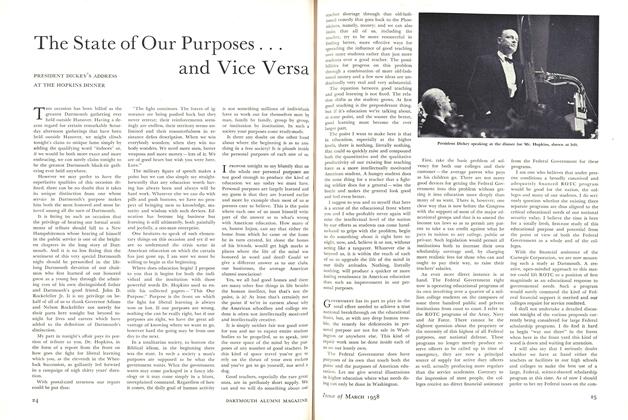

FeatureThe State of Our Purposes ... and Vice Versa

March 1958 -

Feature

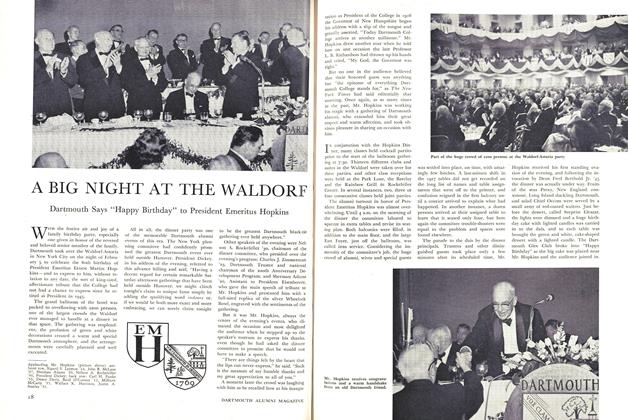

FeatureA BIG NIGHT AT THE WALDORF

March 1958 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Has Record Attendance

March 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

March 1958 By RICHARD W. BOWLEN, WALLACE BLAKEY, JOHN F. RICH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

March 1958 By JOHN A. SAWYER, FRANK T. WESTON

ALAN COOKE '55

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWHAT OF ADMISSIONS AT DARTMOUTH?

October 1961 -

Feature

FeatureWolf-winds at the Doorways

January 1974 -

Feature

FeatureJOHN CAREY

Nov - Dec -

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHoney, They're HOME

January 1996 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79 -

Cover Story

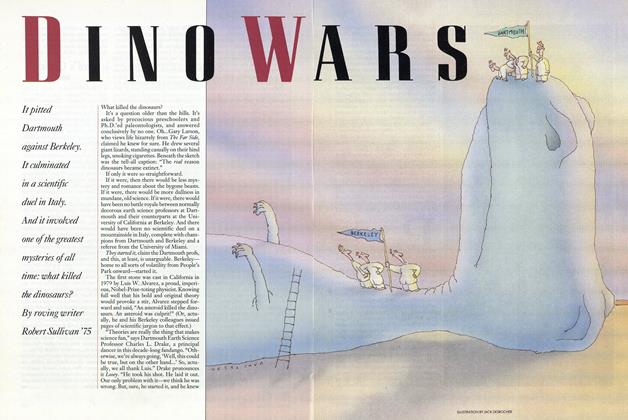

Cover StoryDino Wars

FEBRUARY 1990 By Roving Writer Robert Sullivan '75