Following the award of his honorary degree, President Heuss spoke briefly in German. Following is the text of the translation read to the audience by Mr. Heinz Weber, interpreter with the official party.

IF any American citizen visits me, I say to him, "If you speak slowly, I understand you." He answers, "Wonderful." I say that is all. And we laugh together. Excuse me, I have no experience in English conversation, so Mr. Weber here will interpret the few words addressed to you.

I deeply appreciate the honor of having so old and respected a college confer an honorary degree upon me. When, some years ago, I had the pleasure of President Dickey's visit in Bonn, we discussed neither the' possibility of my visit here nor of this academic honor. Apart from general university matters, we did talk about my friends Carl Zuckmayer and Shepard Stone.*

When it was suggested to me that Dartmouth College was planning to admit me thus into its community, I did not refuse. I did not refuse because I had these two men in mind and also because President Dickey is the sort of man to whom one cannot very well refuse one's cooperation in so friendly an intent.

May I make a remark which I should not like to be misunderstood? In former years, and also in this year, many such academic honors have been offered to me. Sometimes I have refused. The former inhabitants of this land were somewhat familiar to me, as they are to you, through the intermediary of Defoe and Cooper, but in the case of invitations to which I could reply with candor, I wrote thus:

"After all, I am not a Sioux Indian who means to return home from a war of conquest, carrying honorary degrees like scalps on his belt."

The closest friends in the new world, as we in our childhood used to call the American continent, were not the people from New England, nor were they in need of any academic training - instead they roamed along the Mississippi; their names were Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.

I cannot say that these characters of Mark Twain's had any ennobling influence upon me in my small-town childhood, but they left on me the abiding impression that this vast land has adventure in its very blood.

Through a charming coincidence I read many years ago (before I knew President Dickey at all) the history of the foundation of Dartmouth College. I read it with emotion. Alice Herdan-Zuckmayer has described the tough enthusiasm of that Reverend Wheelock who tried to convey to the Indians in this inaccessible wilderness not only Christianity, but also knowledge — what one likes to call "education."

What happened here is a splendid demonstration of the intellectual forces at work during the second half of the 18th century: the so-called enlightenment with its belief in the value of education in conjunction with an intense religious feeling turned towards practical good works.

Now did I come here to tell you something of the history of your college? That would be presumptuous indeed - you, or most of you, know much more about it. But I had to say this, for it indicates the vision which I have associated for many years with the name of Dartmouth.

And here it is that I see for the first time, in tangible form, the pristine glory of early American education - the fact that besides colleges and academic institutions established by public agencies there will remain private initiative in full vigor, the foundation, the kind of institution which merits a special measure of gratitude.

Here is your magnificent library - its glory belongs not only to the State of New Hampshire, not only to the United States, it has also reached us - a memorial to the past, to serve the future.

Alice Herdan has composed what amounts almost to a love song in praise of these library treasures and of the spirit prevailing here. Later she went through the library catalogs to check if there was anything here by the German author Theodor Heuss. She reported to me full of satisfaction this and that and that was registered in the catalog. This flattered me quite a bit. But it is not very much and your new doctor honoris causi has written so much - one of my books has also been translated into English.

I said to myself: "You might send them the missing volumes." In material terms, this is not a big present, but perhaps it will be felt as a symbolic gesture. I should not like to consider the honorary degree awarded to me by Dartmouth College as being the result primarily of the political office which I hold at the present time, although I realize that there is a suggestion of political concurrence in this act. I regard the award of this degree as a gesture of friendly appreciation for many a book on political history, on philosophy, and on the arts which I have written in the course of the years.

I have not written, or at least I have not printed any poems, plays and novels that have become part of the history of literature, like those of my friend Zuckmayer. But to me, who feels so much affection for Carl Zuckmayer as a human being and as a poet, it is a source of great happiness to join him in the community of your great college. A thousand thanks!

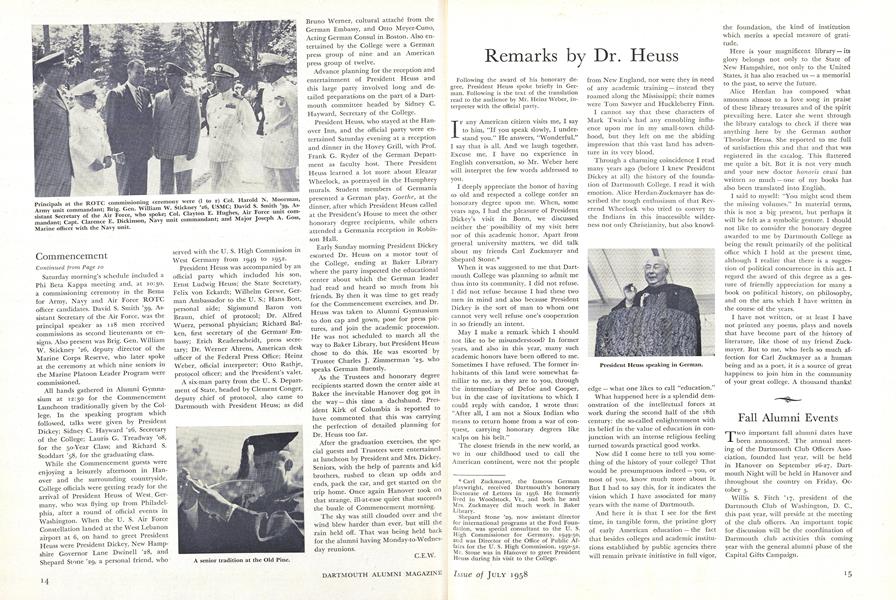

President Heuss speaking in German.

* Carl Zuckmayer, the famous German playwright, received Dartmouth's honorary Doctorate of Letters in 1956. He formerly lived in Woodstock, Vt., and both he and Mrs. Zuckmayer did much work in Baker Library. Shepard Stone '29, now assistant director for international programs at the Ford Foundation, was special consultant to the U.S. High Commissioner for Germany, 1949-50, and was Director of the Office of Public Affairs for the U.S. High Commission, 1950-52. Mr. Stone was in Hanover to greet President Heuss during his visit to the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Examined Life

July 1958 By THE REV. THEODORE M. HESBURGH -

Feature

FeatureThe 1958 Commencement

July 1958 By C.E.W. -

Feature

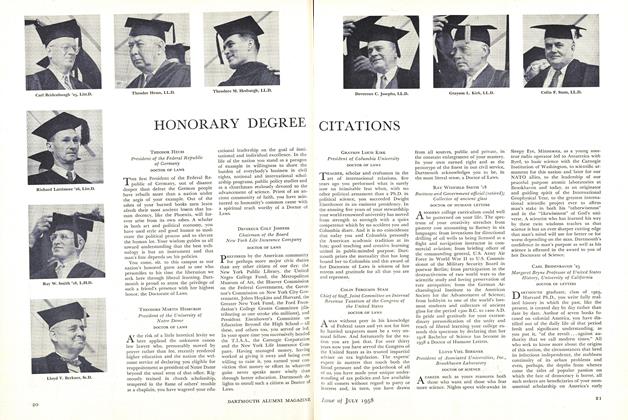

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1958 -

Feature

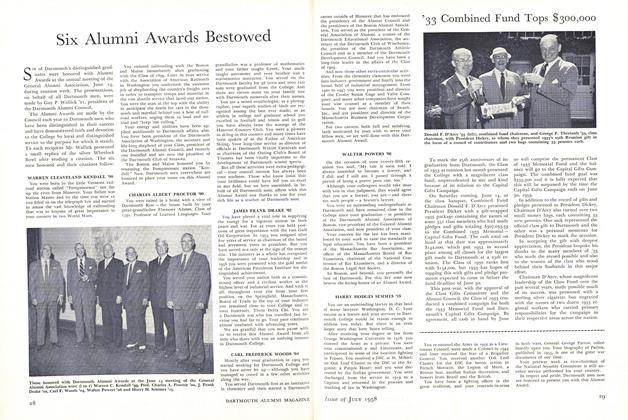

FeatureSix Alumni Awards Bestowed

July 1958 -

Feature

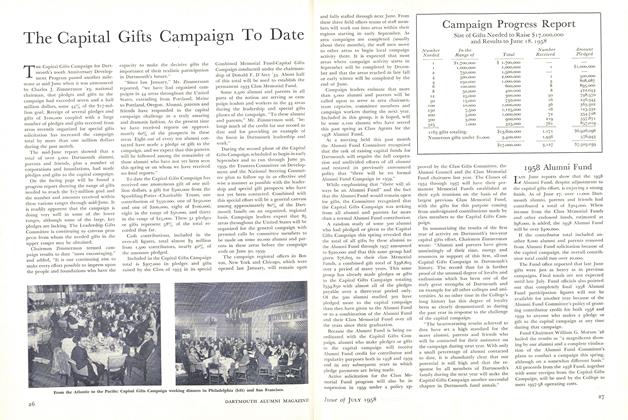

FeatureThe Capital Gifts Campaign To Date

July 1958 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1958 By JAEGWON KIM '58

Article

-

Article

ArticleHonored by Simmons

MARCH 1968 -

Article

ArticleGenetic Engineering: the Question of Ethics

MAY • 1988 -

Article

ArticleCAMPUS CONFIDENTIAL

MAY | JUNE 2016 -

Article

ArticleTHE 1944 ALUMNI FUND

January 1945 By By HENRY E. ATWOOD '13 -

Article

ArticleBOOK REVIEWS

January, 1914 By G.D.L. -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH CLUB OF CLEVELAND

January 1924 By S.S. Larmon