THE COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

C.S.C., PRESIDENT OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME

MANY weeks ago, one of the editors of your student paper called me to ask what I was going to talk about today. I told him at the time, quite frankly, that I did not know, but hoped I would get an inspiration between then and now. I could have told him that I did not intend to subject you to the standard commencement speech we have all heard so often: that commencement means a beginning, that the cold, cold world beyond these ivied halls awaits you with bated, if chilled, breath, and that the bright future and the brave new world are yours to make.

It is not that all of these things are not true, but that they always have been true, for all graduating classes. Almost despite the efforts of many commencement speakers, they continue to be true.

Perhaps the difficulty, or the rub as Shakespeare would say, is that somehow the - graduating seniors have not left their college days with a deep enough personal conviction that it does matter what they think about themselves, their life and times, and the contribution that they will or will not make to the world that will encompass them after graduation.

Meditative reflection, deep-set conviction, personal commitment are hardly the predominant virtues of our day. It is much easier to take ourselves and our world for granted, to assume that somehow we will muddle through life, and life will be good to us. The goals of our day will be our goals: each of you will somehow marry the dream girl, have the pleasant ranch house with a few healthy children running about, progress steadily to a junior and then senior executive position; and let us hope that there will be peace in our times so that this halcyon dream will not be substantially disturbed. True, some of you will idealistically pursue the teaching profession, the ministry, or goverment service, but, for the most part, the future will be cast in Exurbia, in a setting of charcoal-broiled steaks, martinis, and the gray flannel suit.

I am not about to launch into the usual tirade against conformity, but I will say, that if this Madison Avenue picture of your future can be taken for granted, or if it substantially satisfies you, then the faculty here has suffered genteel poverty in vain. The reason why was enunciated long ago in ancient Greece when Plato said that the unexamined life was not worth living. He did not say that it was not pleasant, within the bounds of human tragedy, but that it was not worth living.

Dartmouth has traditionally cherished and pursued the ideal of liberal education in the hope that it might provide you with this one great and lasting value: that you become capable of critically examining yourself, your values, the world you live in, and the kind of life you choose to live. If you take yourself, your values, your world and your way of life for granted, then liberal education has not taken root in your mind and is not guiding your will.

I WOULD ask you, first of all, today to begin by examining yourself. Have you ever calmly and rationally and objectively taken stock of yourself? Why you are alive, where you are going, and why? Are you willing to be just a passive member of a group or of many subsidiary groups, national, cultural, religious, social, or do you cherish your own identity as a person, more than a name or a number, an individual that really matters, who consciously lives a life of his own, freely and rationally, by choice not by pressure, by personal standards not by the impersonal, even subliminal proddings of the mass of your contemporaries? Do you, in a word, live a life of your own, or just a mirroring of everybody else's life?

These are not unimportant, or purely academic questions. If you cannot answer them in a way that establishes you as an individual, then you are indeed living the unexamined life, and your future will really not be worth living, for despite your years in college, you must be considered as uneducated if your life is not consciously rational and deliberately free. God grants us intelligence and freedom, but He will not force us to think critically and to choose intelligently. That is part of our own individual task of becoming an educated person. College is not essential to this process, but it may help. As graduates, you must today answer for yourselves. A diploma, in Latin or in English, is no guarantee that each one of you is what he should be. Here, too, the Greeks gave some terse and good advice: Gnothi sauton — know thyself. Our Lord stated the same truth in an eternal context: "What doth it profit a man if he gain the whole world and suffer the loss of his soul?" Or what will a man give in exchange for his soul?

Here then is the first point that I would make: that each one of you is important, and what you do with your life is important, if only you will take serious stock of yourself and are able to stand on your own feet as an individual person and to make your own decisions as to what you are going to do with your life. St. Paul asked the early Christians to be able to give an account of the faith that was in them. You, too, must be able to explain, at least to yourself, why you stand where you do. Next to being wrong, the worst state is to be right and not to know why, or to be right for the wrong reasons.

THIS brings us to my second point. After establishing yourself as a free and rational person, an individual endowed with God-given dignity and value, the next step in orienting yourself consciously to your times and to your way of life is to consider critically the values you cherish - for values are the wellsprings of human motivation, the guide lines to excellence of human performance.

Let us admit frankly that there are many options in the wide spectrum of possible values, that no one in America is forced to adopt this or that set of values, that not all values are good, that some values are good, not exclusively and all by themselves, but in the context of a total hierarchy of values, with a total range of good, better, and best.

Values, consciously examined and adhered to, are extremely important to the examined life that alone is really worth living. I know of no greater obstacle to the good life than the attitude of denying the importance of values, or of equating all values, good and bad, or, what is perhapps more prevalent in our day, just taking good values for granted. Values, in this, are like wives - if you take them for granted, you are in danger of losing them.

We hear more praise of talent today than of values. Talent, however, is useless, even dangerous, without values. A man of great talent and no values is like a powerful sport car without a steering wheel - there is no direction for the power and no meaning to its journey.

What are the values that press in upon you for allegiance today? I have already casually mentioned the most obvious ones: the values of material security, physical comfort, and ease. These have become almost a national mania in our day. Glance through the advertisements of our popular magazines, endure, if you will, a cross-section of the commercials on television, and you will have undergone as heavy a barrage for these Lowest of all values as man has ever experienced in the course of history. If you just normally exercise your eyes and ears, and if you live the unexamined life, these material values can easily become the substance of your waking hours, the strong focal point of your human aspirations. There is, of course, nothing essentially wrong with material satisfactions and comforts - but just ask yourself: What great human achievements have these values nurtured? At best, they provide a context for gracious living, but man does not live for bread alone. When accepted as ends in themselves, material values are the strongest possible deterrent to the achievement of the really significant human aspirations.

Think for a moment of the other spiritual values that have nurtured the giants of human history: the pursuit and love of truth, that have inspired the great scholars, such as Socrates and Aquinas, who have illumined and guided man's faltering steps upwards through history; the passion for justice, which has given us our great advocates like Coke, legislators like Justinian, statesmen like Adenauer, and jurists like Marshall; the enduring love of beauty in all its forms, that gave birth to the artists who, like Beethoven, have filled the world with music, who have, with Cezanne, brightened our rooms with paintings, and who have lent dignity and grandeur to the simple and lovely aspects of life on earth - a woman's face, a sunset at sea, a child in the park; the intelligent use of human freedom, a value which has been the foundation of stable government, social institutions, and the great humane movements of our times; respect for the dignity of the individual person, which has made possible our courts, our concern for the oppressed minority, the espousal of human rights; compassion for the suffering, which has made our superfluities available to those who need them abroad, has given rise to the great philanthropic foundations, has led men to sacrifice the carefree years of youth to prepare for service and research in the medical profession; capacity for sacrifice, here you begin to understand the value of those who enter the non-lucrative, but highly dedicated professions, the minister, priest, and rabbi, the nurse, the nun, the teacher, the scientist, the foreign service officer, the social worker, the professional military man, the honest and talented public servant; lastly, reverence for things spiritual, without this value you cannot understand our Constitution and Bill of Rights, the simple eloquence of the Gettysburg Address, the motto on our coins, the brave pioneers who built and filled our early churches and schools and Dartmouth, too.

When you think of these values, so much at the heart of Western man, so indicative of the high points of human history, so intimately bound to the inner life and growth and permanence of this beloved country of ours, so inconsistent with the evil spirit that has enslaved a third of the world - when you think seriously of these values and measure yourself against them, I think you will agree that while no one of us will be likely to give to all of these values the full and heroic allegiance they deserve, nonetheless, no one of us can achieve the good life in our times without cherishing the high goals and the human aspirations of excellence that these spiritual values represent.

I have said that this allegiance to higher values must be a conscious choice, a considered conviction, for such is the demand of the examined life which alone is worth living. It is no easy task, to cherish such goals as supreme when our eyes and ears are being constantly pummeled to think mainly of other things: the skin you love to touch, the car more powerful than all others, the refrigerator door that opens and shuts automatically, the cigarette that tastes better and still goes easy on your lungs, the beer that is brewed better than all others, the coffee that won't keep you awake, the barbiturate that will put you to sleep. A consumer society must expect these pressures, but it need not accept them as shining goals for all human aspirations or else our society will become so shoddy, so superficial, even meretricious, as to become unbearable to those who still think and judge and cherish on a level slightly higher than that of titillated-sense life.

THIS thought, I think, should bring us to our third point: that just as the educated man today cannot take himself or his values for granted, the world, or the particular times in which we live can stand and should have conscious examination, too. Speaking of values, we have necessarily become involved somewhat in the examination of our times, but I would like to take a different tack now, on a broader base leg.

There are elements of great danger in our times, but as Toynbee has said, it is the really great challenges that have called forth the equally great, civilization-founding responses. It would seem to me that our times are made to order for the young who traditionally have had the capacity for high adventure. Adventurous may not be the proper adjective for our times, but it seems to me that never, since the discovery of the new world, have there been so many opportunities for the young man who will not allow himself to be seduced by the easy way, the safe choice, the altogether secure haven.

Broadly viewed, our times face these great challenges: first, a diametrically opposed system of thought and action that has taken over one-third of the world's people and territory and now challenges us to prove to the other, uncommitted third that our system is better. While there is great evil in. this situation, there is also the possibility of great good, for now we must examine and buttress our own unique spiritual strengths and demonstrate through higher motivation and more excellent performance that we really believe what we have too often and too long taken for granted.

The second challenge might be called the explosive scientific revolution that has gone far in harnessing the earth's powers and is now vaulting the space beyond. Inherent in this challenge is whether we will be able to master in a human and humane way this Promethean power within our grasp, whether we will be able to use it for the good of mankind and not for his destruction, whether in the face of these new and dramatic scientific values, which are also good and extremely useful, we will be able to maintain the balance and the supremacy of those older and better treasures of mankind - the humanistic values that you have learned here at Dartmouth - the values that alone provide a human framework for science, a direction for its power, a meaning for its contribution, a family in which it can be an honored, but not a sole member. We fear the scientific and technological power of Russia, not because this power is essentially bad, but because without the supporting framework of a humanistic tradition and policy, it can become as dangerous as a bomb in the hands of an idiot. Power, scientific or otherwise, is meaningful and fruitful in the world of man only when it reckons with those deeper spiritual values that we spoke of earlier, and these values come from outside the realm of physical science.

A third great challenge of our times comes from the revolution of rising expectations in the third of the world that is yet underdeveloped. We in America will sleep uneasily on our Beautyrest mattresses if we remember that a third of mankind has gone to bed hungry. We may enjoy our banquets less if we remember that half the world's children have never seen milk or medicine. We can say this is none of our business, but that essentially is what the first murderer said: "Am I my brother's keeper?"

Related to this third challenge is another anguish of our own country: Should one-tenth of the American people, long ago granted full citizenship, be citizens in fact or in fiction? You may dismiss this challenge, too, but then remember that the uncommitted third of the world is not white, but colored, and while our political theory sounds fine in every language abroad, the strongest language everywhere is what we do at home.

There are, of course, other basic challenges in our times. For example, how can we educate more young people than any one nation has ever attempted to educate, and still hope to maintain excellence in the process, as indeed we must, if America is to be enabled to bring to bear upon its great current problems the totality of the nation's human talents and capabilities and skills.

Rather than extend further this assessment of the challenges of our times, may I assume at least that ours are not dull days, unless we insist upon being dull people and, in that event, we shall not long survive.

THIS brings us, without, I trust, too great a strain on logic and coherence, to my fourth and last basic point. This last question that I would ask you to put to yourself today is answerable only in the context of what you think of yourself, your values, and your times - the first three points of our discussion - if I have not lost you along the way. The last question is: What are you going to do with your life?

May I suggest, before you answer, that unless your ambition is to be a bank robber, a gigolo, a confidence man, or something similar, the specific profession you wish to follow is not overwhelmingly important. God and man are served in myriad ways - all of them good. But the point most at issue for the graduate of today is the spirit in which you are going to do whatever you plan to do. I suggested earlier that too many Americans today are espousing false values of luxuriant ease rather than hard work, material gain rather than human and spiritual service, hide-bound, built-in security instead of adventure, dedication, and the capacity to sacrifice oneself to a higher and loftier purpose.

You must occasionally have meditated upon that famous paradox of Christ, Our Lord: "A man must lose his life to gain it." I think that Our Lord meant this, at least: that if a man lives completely and exclusively for himself, only for his own comfort, security, and well-being, he will in the end have just this and nothing more — himself, and the things that alone are incapable of making life worth living. On the other hand, a man who selflessly devotes himself to others and their welfare in the end finds his life rich in meaning, significance, and happiness. In losing his life to others, he has paradoxically gained a better, a finer, a fuller life for himself.

May I suggest that each of your lives will have in it just that measure of meaning, significance, and happiness that is derived from the challenge, the nobility, and the grandeur of the goals to which you dedicate your educated talents. If your life becomes only full of yourself, it will indeed be empty. But if your life is cast in the context of service to God and men, it will surely be a full life, worth living, and of eternal value. And when we say your life, it must be viewed in the broadest possible context: your daily work, your marriage and family, your neighborhood, your civic commitments, your recreation - yes, and your religious life, too.

Fortunately, you have been educated for this broader service at Dartmouth - you have been given a reverence for the mind at work throughout the broad range of universal knowledge. You have learned, I trust, to keep on learning about God, man, and the world by every legitimate means, be it divine revelation in theology or human reason ranging through all the liberal arts that can free a man, with the help of God's grace, from the bondage of ignorance and easy answers, from pride, prejudice, and passion.

Your own President once summed up the blessing of a liberal education when he said, "The American liberal arts college can find a significant, even unique, mission in the duality of its historic purpose: to see men whole in both competence and conscience." President Dickey added a note that underscores all that I have been saying. He spoke of the need for honest humility, compassion, and faith that become personal through the experience of life's tragedies. Then he concluded: "An undergraduate who has not yet known these things in his own life can sometimes borrow from the total store of human woe and joy, and by using the tools of the intellect he can begin to lay out a pattern of belief for himself, but it will be a sharper etching after the bite of life's acid is on it."

All I have said today can perhaps be best summed up in these words: that your greatest opportunity at this hour is to lay out a pattern of belief for yourself. My prayer for all of you today is that your personal pattern of belief will do justice to all that you are and all that you might yet be, as a person, intelligent and free, that your pattern will reflect the values that make life meaningful and worth- while, that your pattern will be adequate to meet effectively, positively, and courageously the total human situation today, and ultimately, that by faithfully following your pattern of belief, each of you will somehow, God willing and helping, make incarnate in your life tomorrow the high aspirations, the true dedications, the personal commitments, the symphony of all good things that make the angels rejoice and the earth fruitful.

God bless you.

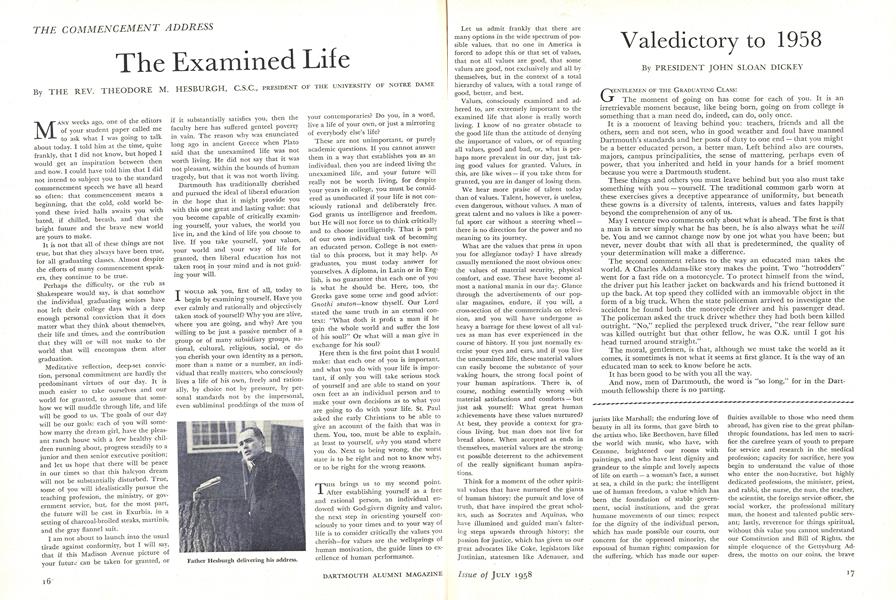

Father Hesburgh delivering his address.

An innovation for Commencement this year was a community art show at College Hall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe 1958 Commencement

July 1958 By C.E.W. -

Feature

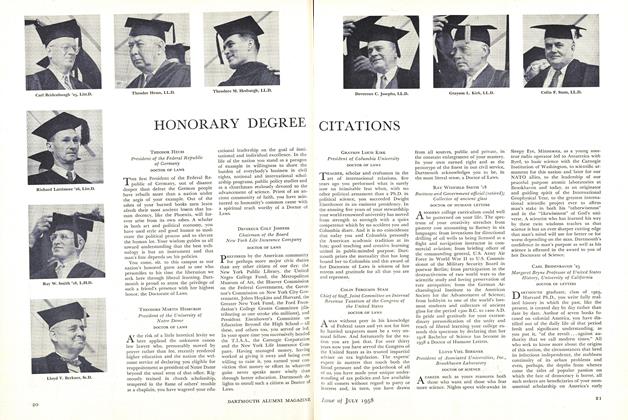

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1958 -

Feature

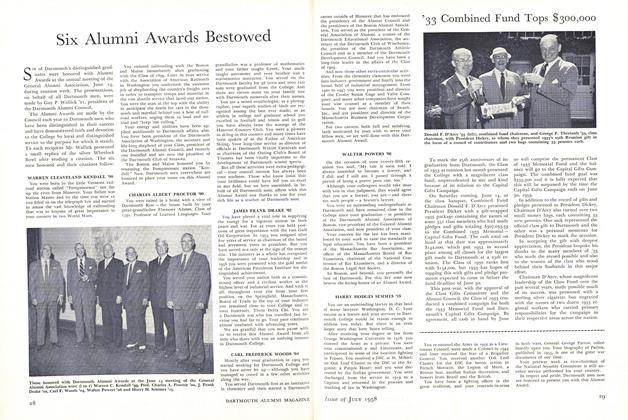

FeatureSix Alumni Awards Bestowed

July 1958 -

Feature

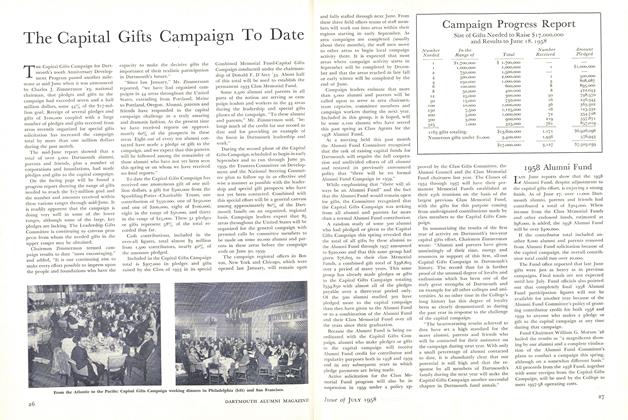

FeatureThe Capital Gifts Campaign To Date

July 1958 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1958 By JAEGWON KIM '58 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1958 By LAURIS G. TREADWAY '08

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Classic Tradition of Judaism

FEBRUARY 1968 By JACOB NEUSNER -

Feature

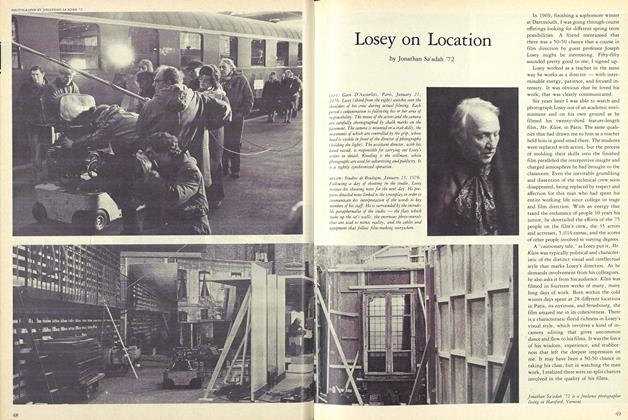

FeatureLosey on Location

November 1982 By Jonathan Sa'adah '72 -

Cover Story

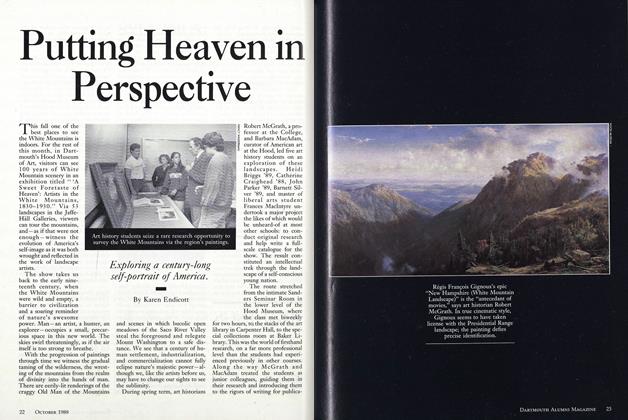

Cover StoryPutting Heaven in Perspective

OCTOBER 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

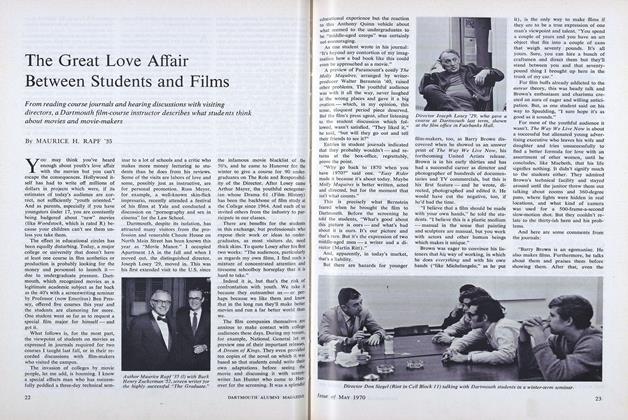

FeatureThe Great Love Affair Between Students and Films

MAY 1970 By MAURICE H. RAPF '35 -

Feature

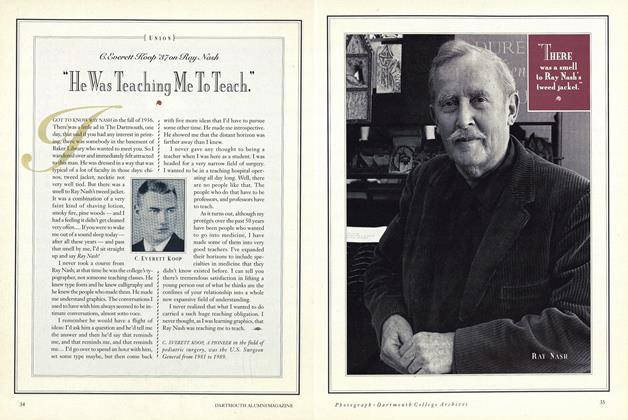

FeatureC. Everett Koop '37 on Ray Nash

NOVEMBER 1991 By Ray Nash -

Feature

FeatureMoney and Luck

MARCH 1999 By Regina Barreca '79