The death oftwo studentscalls for asmall actof redemption:this story.

Just before the 1991 summer term, two Dartmouth graduate students were murdered in their sleep. It happened in Hanover. The papers covered it for about a week. Even in Hanover, where people kill each other only very rarely, a murder probably isn't as shocking as it used to be. It is a peaceful town, but Hanoverians are Americans nonetheless, and Americans are a violent people as a whole. The older residents were reminded of the last time someone deliberately killed someone else. In 1948 a housewife out in Etna shot her husband and turned herself in to the police next morning. The last time somebody killed a student was in 1949, when a group of students beat up a classmate, who died when he hit his head against a radiator.

The 1991 murder had to do with a love spurned. Hanover police arrested the perpetrator immediately, and he was sentenced to life in prison. For anyone who reads the paper or watches television, it is difficult to make this murder stand out from the daily litany of violence—except that it was in Hanover, and neither the victims nor the murderer were Americans, and the crime was done with an ax. The story of the murder itself is gruesome but not all that unique. Angry lovers, lives cut short—crimes of passion are delivered for us wholesale in this country. But there is a wider and more important story that has to do with the two women who were killed. They had escaped a larger and even more brutal tragedy, only to fall to a smaller and more personal one. Unless we know the story of these women, there is the danger of still another tragedy: that we will forget them and what they stood for. Dartmouth, in particular, must know what it lost so that it can save what there is to save of the two women.

Selamawit Tsehaye and Trhas Berhe were graduate students in physics. Both were 24 years old, and both were from Eritrea, an Ethiopian province that was fighting a bloody war for independence. .The two women did everything together. Neighbors, who called them Selam and Teri, say they were never seen separately. They went to classes together. They did labs together, they even on occasion team-tutored undergraduates. "Only when they had to—when one of them had to tutor someone or do a lab or something—would they split up," says Ken Davis '94, who was tutored by the women. "But immediately after, they'd hook right back up."

On Sundays they would both walk across Summer Street to `attend the Reverend John Lemkul's Our Savior Lutheran Church, where they got to know some of the townsfolk. Many nights they could be seen studying at Our Savior, very occasionally engaging fellow church members in light conversation. Teri and Selam seem to have been extremely well liked. The congregation considered them to be under its collective wing, often inviting the women over for dinners. Seldom was there a church function the women failed to attend.

While the two students were friendly enough, they were not exactly gregarious. They had much contact with their church group and the people they worked with in the physics department, but beyond that the two were somewhat reclusive, preferring to spend nights studying at the church rather than going out with friends. They were graduate students, very serious about their work. And they were good at it.

Selam arrived in the States intending to earn her doctorate in order to return and help rebuild her country by teaching. Teri, a friend from their undergraduate days at Asmara University, came to escape Ethiopia. With guidance from some Dartmouth administrators, she was seeking political asylum.

In Hanover they spent much of their time in the physics department, concentrating on the task immediately before them.

"They always smiled and spoke to you," says Connie Elder, an administrative assistant in the physics department. "They, not like many of the graduate students, would come by the back door so they could walk by our desks to see us."

"And they would always say good morning," adds Judy Lowell, another administrator in the department. "They were always polite and meticulous, but more than that, they were genuinely friendly." Lowell and Elder first met Selam when they were supposed to take her picture for the rogues' gallery of physics graduate students to be displayed in Wilder Hall's basement. "Selam had to take time in considering how

to be photographed for the rogues' gallery," Elder says. "It was important for her to make sure it was just right." Selam fixed her hair and worried about the dull lighting. She then, for a short time, insisted she should change her clothes.

"That really struck me," Lowell says. "It was the same as in our culture. Selam wasn't conceited, she simply thought it important how she was presented.'"

Professor Jay Lawrence remembers their enthusiasm. They would invariably be the first to come in for office hours with questions on the homework. At first he was impressed that they had always given a good go at the work before coming in. Then he was surprised to see them coming in with questions on problems he hadn't assigned. "They were insatiable," Lawrence says. "I had to slow them down sometimes They were just so enthusiastic."

Both were prepared to immerse themselves in their physics once again that summer of 1991. Spring term had been out a couple weeks. Summer term was to start in a couple of days.

Few places could have seemed more different to the women from wartime Eritrea than Hanover. The interim between spring and summer classes makes the place even quieter than usual. Many residents say it is the best time. The two hot dog vendors out in front of Town Hall eye each other warily in the sun. Even the dogs are scarce. Only Buildings & Grounds seems active, attempting to accomplish a term's maintenance in the two or three weeks the students are gone. Hanover Police see a sudden drop in noise complaints, public drunkenness, and traffic. They eat more donuts than usual.

Like many graduate students, Selam and Teri stayed on campus. Their families were still in Eritrea, a land that had been seized over the past couple of centuries by the Portuguese, Turks, Egyptians, Italians, and Ethiopians. The Eritreans are traditionally a trading people, having conveyed goods among other peoples around the Red Sea and the Upper Nile. The region was never very wealthy. Agriculture accounts for almost half the gross domestic product, with coffee being the major export. Three major famines struck in recent years—1972, 1984, and 1989— and killed as many as two million people. Starvation was a tool used by the Ethiopians in an attempt to subdue the Eritreans.

Eritrea had become federated with Ethiopia in 1952, and then in 1962 Ethiopia forcibly took over the land. For four decades the Eritreans fought back. Remarkably in the midst of cluster bombs and napalm dropped from Soviet MiG 23s, they established a network of underground schools and hospitals.

It was from this context that Selam and Teri fled to America. They had risen through the highly competitive ranks of Eritrean underground academia to attend the University of Asmara. They were Eritrean models of success in a culture that stressed education as few others do. The two women were among the struggling nation's most valued assets: its nascent intelligentsia. But they had not escaped the violence entirely; both of their fathers were killed while the girls were still young. They spent their first several months in the United States trying to extricate friends and relatives. Selam attempted to bring her brother into the United States from India, where he held an expiring student visa. Teri was trying to recover a sister and a nephew from a Sudanese refugee camp. Teri herself had to acquire political asylum in order to stay in this country; she had the help of Dartmouth administrators and a Yale Law School class that took on her case as a class project.

Throughout their stay, local groups helped them financially. The town of Hanover helped out with rent, and the local church took over their expenses. Carole Gause, a member of Our Savior and one of the people to speak about the two at the Lutheran memorial service, says that the church "practically adopted them."

Although they were deeply private people, Selam and Teri quickly became central figures in the local Lutheran community. Their extraordinary politeness, a trait said to be common among Eritreans, endeared them to other parishioners. Some would say they were almost overpolite. Neither of the women would allow themselves to walk with the Lemkuls. They would always lag a few steps behind. And they would never allow guests who came over for dinner to help with the dishes. "They were exceptionally sharing," noted the reverend. "The only thing that came before the church was their studies." (They missed only one service, because of a conflicting exam.)

And they loved to share this faith they had. They would often talk to parishioners about their beliefs, and about the customs of their native church, the Makane Yesus (an Ethiopian form of Lutheranism). On Christmas Eve both women wore completely white native celebratory dresses to services and told curious churchgoers about the shared religious customs of the Lutherans and the Makane Yesus.

On Palm Sunday, Selam and Teri took the palms that the Summer Street church traditionally distributed and wove them into elaborate rings. Mrs. Lemkul recalls Teri telling her, "This is worn from Palm Sunday to Easter in Eritrea," as she handed her the woven ring as a gift.

They also shared their time with people who were lonelier than they. After news of the murder spread through the town, an elderly woman showed up at the minister's home and asked to have the full names of Selam and Teri written down. The woman could not read or write, and she handed a piece of paper to Mrs. Lemkul and said the two had visited her regularly in the senior-citizens apartment down the street for almost a year. She simply didn't ever want to forget those names. Other people turned up at the Lemkuls' house with similar stories—people whose lives the two women had quietly touched.

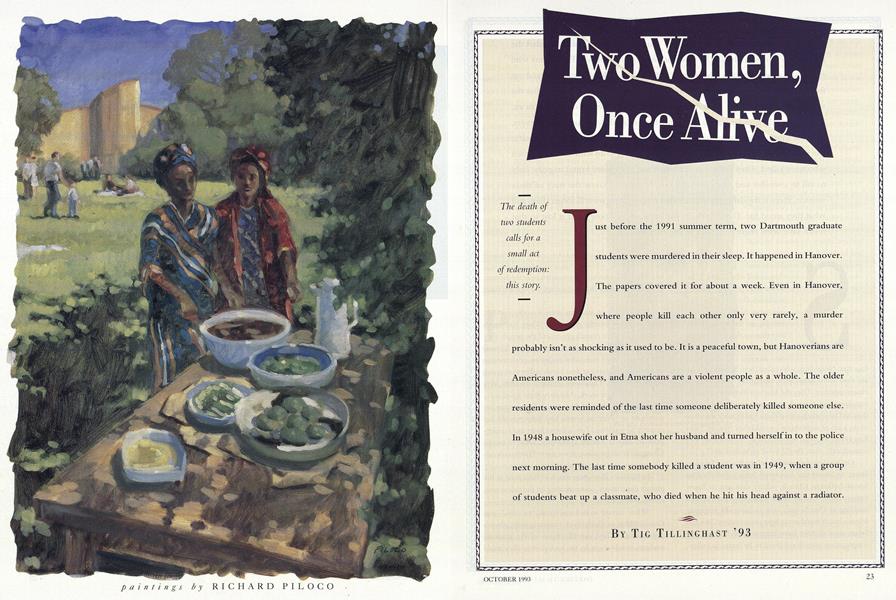

There were, for instance, the people who had taken the Ethiopian cooking course the two Eritreans co-taught at the Hanover Food Cooperative. The Co-op eventually asked Selam and Teri to make all the Eritrean food they could remember. They attracted crowds of Hanoverians, some of whom came for the food, others who came to see the colorful Eritrean dresses the two women donned just for such events. (Except for these times, they always seemed to be wearing exceptionally warm clothes against the Hanover climate, no matter what the season. "They were always encased," recalls the minister's wife.)

The women also cooked their spicy dishes for the church potlucks; the reverend politely asked them one day to tone down the seasoning a wee bit.

Mrs. Lemkul remembers a particular act of generosity. After one church service, some parishioners sang "Happy Birthday" for Mrs. Lemkul at a post-service reception. Neither Selam nor Teri had known it was her birthday, so they immediately went back to their apartment and returned with a framed poster of a famous monument in Addis Ababa—a poster that had been hanging on their wall to remind them of their homeland and of their mission.

The minister admired the women for their fierce determination and dedication to their studies: "Their goal was to return to Asmara for teaching—for helping their country. They wanted to return." Selam would occasionally point out to those who asked that all of her professors back in Eritrea were European. There weren't any native teachers. Selam and Teri were to be the first.

They were not the only Eritreans to go to graduate school abroad, of course. Another was Haile Selassie Nega Girmay, a soft-spoken doctoral candidate in geophysics at Sweden's University of Uppsala. He had been there eight months before traveling to Hanover last summer for a visit with Selamawit Tsehaye, the woman he wished to marry.

Laust Pedersen, an Uppsala University professor who advised Girmay and was perhaps the closest to him during his eight months in Sweden, says Girmay was a brilliant student—quiet yet clearly determined. Girmay struck Pederson as an honest and thoughtful man, and it came as a great surprise when one day he up and left for the United States without telling a soul.

Pedersen hadn't known that back in Ethiopia, just before leaving tor his doctoral studies, Girmay had proposed to Selam. She accepted an offer from Dartmouth College just about the same time he received his offer from Uppsala. She also accepted his proposal. But for reasons that may never be fully known—perhaps sheer distance or perhaps a lack of adherence to the strict Eritrean matrimonial codes— the relationship began to sour. Friends of Selam say she had grown out of the relationship.

Girmay met most of the women's friends in those weeks he spent with them in their Summer Street apartment in Hanover. Dartmouth professors and students who became acquainted with him repeatedly used the same two words to describe him: quiet and measured. Professor Jay Lawrence and graduate student Ben Bromley dined with the three Ethiopian students on a Sunday night, June 16. Girmay seemed charming, if a bit reserved. There was nothing in his demeanor to show that he had for the previous week been hiding an ax bought from the Kmart in West Lebanon.

That same night, two Hanover police officers responded to a distressed caller: a medical student who had been startled by screaming in the middle of the night. She had been up studying for a physiology exam and washing some laundry. Hanover Police Supervisor Patrick O'Neill just out of police academy—thought he and his partner had better swing by. They spoke with the med student and then were heading back out into the cool night when O'Neill spotted a light on in apartment number three. He stopped and knocked on the door.

Girmay answered the door, shook Officer O'Neill's hand, and said, "I killed them. I killed them both with an ax." Later that night, O'Neill would discover blood on his own fingers from having grasped Girmay's outstretched hand.

In searching the apartment, police found Girmay's packed black suitcase containing, among other things, $4,300 in American currency. Twelve hours later, two policemen led Girmay into a tense Hanover municipal courtroom for arraignment on two counts of first-degree murder—a charge that carries a mandatory life sentence without parole in New Hampshire.

At the trial, the defense, led by public attorney George Ostler, pleaded insanity. The jury listened to a two-hour taped confession in which Girmay described how he and the two women had met back at the university in Ethiopia. He detailed how he and Selam fell in love and how she more recently began criticizing him, eventually calling the relationship off just days before the murders.

Girmay wove an occasionally tangential story about love and his home culture. Ethiopian tradition requires that the parents of a suitor negotiate with the parents of a potential bride in order to arrange a marriage. In February of 1991, Girmay broke this tradition by appealing directly to Selam's family for her hand in a letter. Girmay surmised that because the letter never got a response Selam may have felt this signified a rejection of him by her mother. Things climaxed with an argument in a Hanover restaurant. Soon alter, Girmay took a taxi out to West Lebanon to purchase an ax. He said he prayed to God to help him stop what he feared he would do.

The jury found Girmay guilty on March 2. Judge Smith then imposed the automatic sentence of life imprisonment for each charge without the option for parole.

The trial itself seemed a rather eerie affair. Not many observers attended, and no family members or representatives of the victims ever made an appearance. And with Girmay not present for much of the trial, one court officer told the Valley News, "It's turning into a victimless and defendantless case."

Colleagues and acquaintances, however, spent as much time as they could afford observing the trial. Lowell, the physics department administrator, would later say, "I needed to bring some closure to this."

Connie Elder added, "I needed to go [to the trial] and listen to everything. It was difficult, but I was glad I did. A lot of questions were answered that wouldn't have been otherwise, without sitting right there in the courtroom."

The New Hampshire victim/witness advocate, Linda Juranty, kept the families of the victims informed of the trial's progress, as they could not afford to attend themselves. She said there didn't seem to be any close friends in attendance, probably because the victims had been at Dartmouth only a year.

After the women's deaths, the smallish Eritrean community that lives in Boston made their way up to Hanover for the Lutheran memorial service. Local parishioners looked on as all the Eritrean women lined up along the road and began to wail in mourning.

Outside the physics department, the reaction on campus had been much more subdued, in part because there were so few people around. Most students did not hear of the crime until they arrived for summer term. The murders had hardly made a blip in the national press—little outside the Northeast, a blurb in the New York Daily News, a blurb in the Boston Globe, nothing in The Times. In another era, a double ax murder would have caused a national sensation. But what was another pair of murders these days? And what were the deaths of two more Ethiopians among the millions who have starved or been bombed or shot?

Once the returning College community heard the news, the shock did not seem to register very strongly. Several factors distanced people from the horror: the fact that the news was several days old, that the women were not well known beyond their department and the church, that they had not been in this country or this community very long, that they were graduate students—members of a group that has traditionally suffered from collegiate ambivalence. Besides, it is a human trait, and perhaps a healthy one, to distance oneself from death and violence. We cannot take eveiy death personally and stay sane. But now and then, for the sake of our own humanity, we must look beyond ourselves and see a greater loss. Why remember Selam and Teri, when there are so many other human stories to tell? Because they were a part of Dartmouth that gets forgotten too often, because we can learn something from their story, some old notions of heroism and love. Mostly, though, we must remember them for our own sake. There is a point at which the distancing must stop, when we must see the loss as our own. Briefly as they were at Dartmouth, Selam and Teri were our students, they were a part of us. Through knowing them we know ourselves.

Last June 13, eight physics students graduated with new Dartmouth Ph.D. degrees, five fewer students than the number that started the program. Two had married and moved to different schools. One had dropped out soon after a professor politely told him that he might want to try math instead. The other two were Selam and Teri.

Girmay now awaits appeal, imprisoned in North Haverhill, where in all probability he will spend the rest of his life. One court observer in the original trial noted, "There were really three lives lost in this case.

Both mothers of the victims still live in Addis Ababa. Their fathers were killed years ago in the Ethiopian violence. Various brothers, sisters, and cousins continue to seek asylum in other countries.

School started at the University of Asmara a month ago. According to the registrar, no native Ethiopians are teaching.

A former editor of The Dartmouth, TIG TILLINGHAST now works for Leo Burnett in Chicago.

The two Eritreans were "insatiable" intheir studies, according to their professor.

Residents of the senior-citizens center recalled regular visits by the two young women.

Few places could have seemed stranger than Hanover.

Girmaywove alongstoryaboutloveand hishomeculture.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

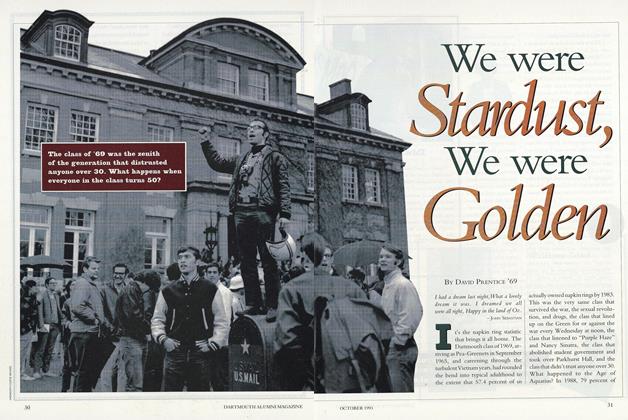

Cover StoryWe were Stardust, We were Golden

October 1993 By David Prentice '69 -

Feature

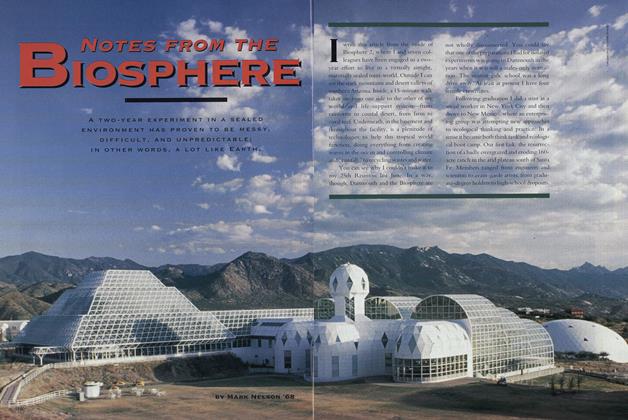

FeatureNotes from the Biosphere

October 1993 By Mark Nelson '68 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

October 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleThe Daughters of Eve

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

October 1993 By Thomas G. Jackson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

October 1993 By Amy Iorio

Tig Tillinghast '93

-

Article

ArticleThe Second Four Years

September 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Article

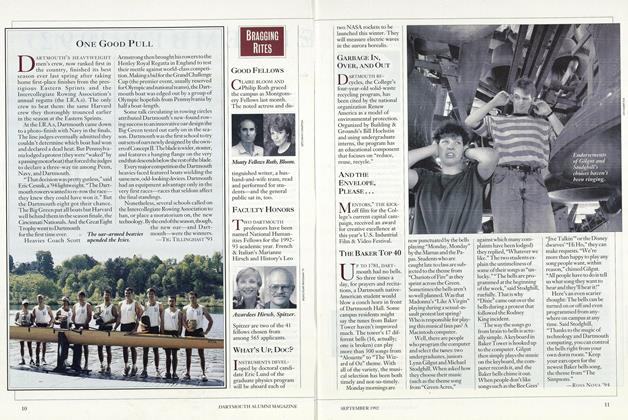

ArticleOne Good Pull

September 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Article

ArticleA Leader of Gay Journalists

October 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Article

ArticleThe Anti-Doctor Doctor

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Cover Story

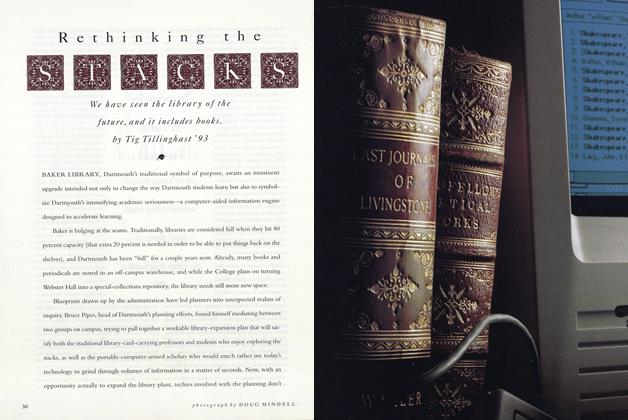

Cover StoryRethinking The Stacks

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Feature

FeatureCure1 For The Common Cold2 Proven3 At Dartmouth4!

December 1992 By TIG TILLINGHAST '93

Features

-

Feature

FeatureJohn D. Rockefeller Jr. Gives $1,000,000 To Fund for Building the Hopkins Center

July 1956 -

Feature

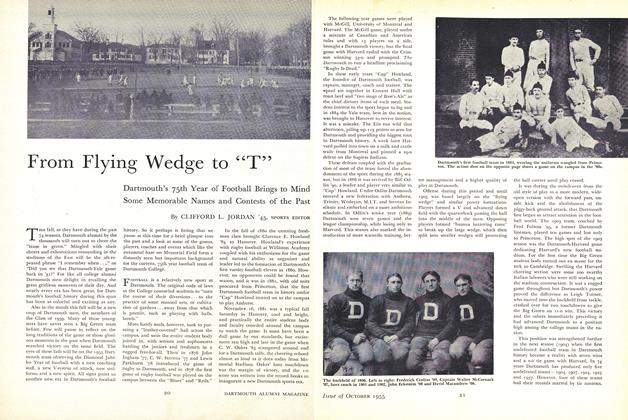

FeatureFrom Flying Wedge to "T"

October 1955 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45, SPORTS EDITOR -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Productivity

March 1996 By James Wright -

Cover Story

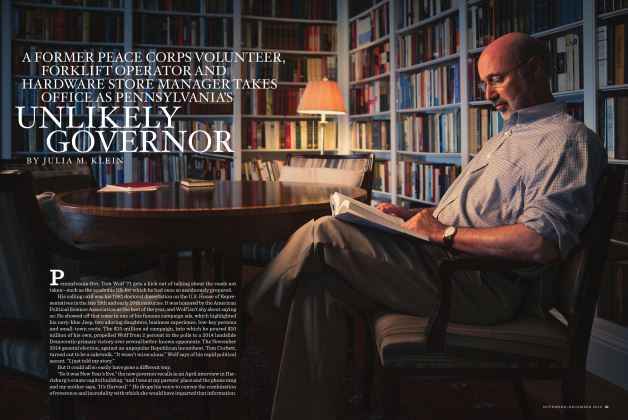

Cover StoryThe Unlikely Governor

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1962

July 1962 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY