By Douglas Alden '33 New Brunswick, N. J.: RutgersUniversity Press, 1958. 367 pp. $6.00.

To the excellent series of works dealing with eminent living French writers published by the Rutgers University Press, Professor Douglas Alden of Princeton has contributed an exhaustive biographical and critical study of another contemporary man of letters, the novelist Jacques de Lacretelle. Little known in the United States (only three of his novels, two short stories, and a travel essay have been translated), and bypassed in his own country by a meteoric succession of literary movements, de Lacretelle should gain many new readers as a result of Professor Alden's sympathetic study.

The book's two brief initial chapters deal with de Lacretelle's family background and take him through his troubled adolescence, military training, and uneventful wartime service. Professor Alden then concentrates primarily on a detailed analysis of successive literary efforts, while keeping "a thread of biography" running through the remaining chapters. Born at Cormatin, Saône et Loire, in 1888 the novelist inherited from his bourgeois ancestors a distinguished record in the learned professions, an affinity for the pen, and a strong legacy of nineteenth century positivism. The -novelist's own life is perhaps best characterized by diffidence, a meticulous devotion to his craft, as well as a constant refusal to espouse artistic "isms" or political ideologies.

Professor Alden sees de Lacretelle's literary career as essentially a series of oscillations between a nineteenth century and a twentieth century point of view in art, between objectivity and subjectivity. His first work, La Vie inquiète de Jean Hermelin (1920), depicts the author's painful adolescence in emotional yet delicately restrained terms. Silbermann (1922), a moving account of a brilliant, erratic Jewish youth's ostracism, retains the illusion of subjectivity; the protestant narrator, Silbermann's youthful friend, becomes deeply involved and grows to emotional freedom through this tragic friendship. Although the obsessive modern theme of sexual inversion runs through La Bonifas (1925), the creation of a whole society, the use of third person narrative, and the "physiological fatalism" dominating the characters, recall sharply de Maupassant's realism. Through reading Rousseau the author again returns to instrospection, breaking down the barriers between confession and fiction in L'Amour nuptial (1929). A tetralogy, Les Hants Ponts (1932-36), the saga of a provincial family's decline, rejoins the documented realism of the nineteenth century by its very theme, its more detached third person narrative, and its large number of living, autonomous figures. Le Pour et leContre (1946), while masking its subjectivity by the use of impersonal narrative, clearly projects de Lacretelle's own deep personal concerns through the hero's literary vicissitudes and complex marital relationship.

Professor Alden's study is well served by ample documentation, a complete bibliography and an excellent index. His judgment that de Lacretelle's literary reputation ultimately rests on his unobtrusive, lucid style, rather than on mannerism or shocking subject matter, is amply borne out by his study.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHistory and Moral Responsibility

July 1959 By CHARLES H. MALIK -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1959 By JOSEPH W. WORTHEN '09 -

Feature

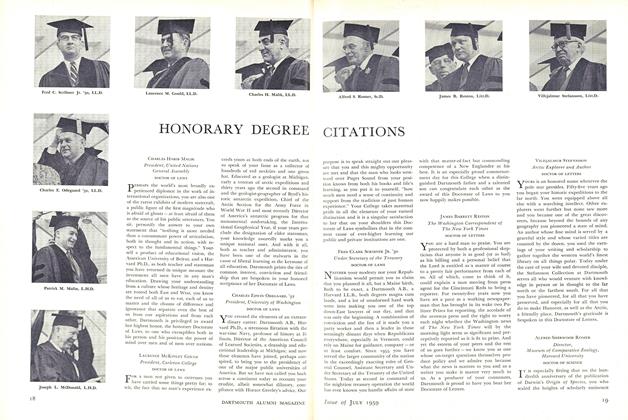

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1959 -

Feature

FeatureFor Distinguished Service . . .

July 1959 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1959 By JOHN E. BALDWIN '59 -

Feature

FeatureThe 190th Commencement

July 1959 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

Books

-

Books

BooksGAUSERIES—LA VIE SCOLAIRE,

November 1949 By Charles R. Bagley -

Books

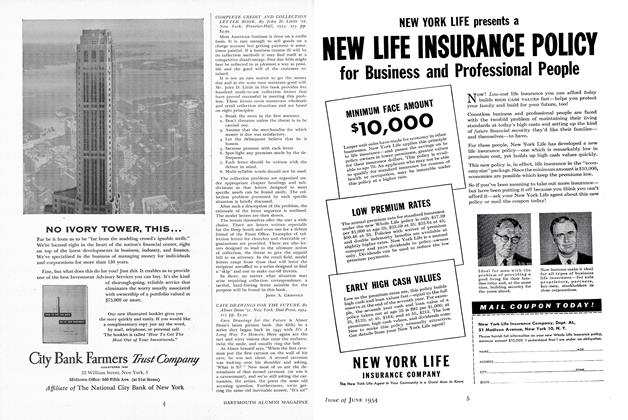

BooksCAVE DRAWINGS FOR THE FUTURE.

June 1954 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Books

BooksTHE MOLLY MAGUIRES.

DECEMBER 1964 By EDWARD C. KIRKLAND '16 -

Books

BooksX-RAY AND RADIUM IN THE TREATMENT OF THE DISEASES OF THE SKIN.

MARCH 1968 By LESLIE K. SYCAMORE '24, M.D. -

Books

BooksGENERAL AND SPECIFIC ATTITUDES

MAY 1932 By Maurice H. Mandelbaum -

Books

BooksHURRAY! I WENT TO THE DENTIST TODAY!

MARCH 1970 By RICHARD L. SMALL, D.M.D.