The Address at the Cornerstone Ceremony

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ASSOCIATION OF AMERICAN MEDICAL COLLEGES

THE revolution in medical education that followed the Flexner Report of 1910 was really precipitated by the fact that the then-developing body of scientific knowledge was not being translated into medical practice by the then-existing system of medical education. The gap between what was known and what was taught was unnecessarily wide and would have continued to widen further if most of the nation's sub-standard schools of medicine had not gone out of existence and if most of those that remained had not bolstered their educational programs by adding qualified medical scientists to their faculties, by introducing research as part of their academic function, and by raising their standards of admission and education accordingly.

And now almost fifty .years later we find again that medical education has much in common with the era of the Flexner Report - the gap between what is known and what is taught is once more becoming wider than can be justified. But this time the gap is widening for reasons that differ from those that accounted for the difficulty a half-century ago, for instead of suffering from the blight of pedestrianism we are belabored by the fruits of progress - progress within medicine itself and progress within the society in which medicine must serve.

Since the war, new research tools, methods and concepts are making it clear that we are approaching a much broader and deeper understanding of basic human biology than we ever dreamed of before. The use of radioactive isotopes and the development of many new methods of molecular analysis and electronic measurement, together with startling progress in the fields of computation, microscopy, microchemistry and tissue culture, are leading our scientists into more meaningful studies of cell genetics, cell function and cell differentiation, and this in turn to a better understanding of the factors involved in normal and abnormal growth and biological damage and repair. Also these and other new concepts, methods and tools are leading to advances in psychology, psychobiology and psychopathology, which in turn will permit us a better understanding of human mental and emotional processes, the development of human personality, and the evaluation and management of interpersonal relationships. Other research, much of it statistical and epidemiological in character, can now evaluate factors in the working and living environments of our people - factors long suspected of being important to health and illness. And finally the time has come when research in the socio-economic aspects of medicine is pointing the way to a better understanding of the distribution, availability, administration and effectiveness of medical service.

In other words, it can be said that research is now producing a body of knowledge that is of first importance to all of human biology and medicine. The potentialities of medical research and service have come to be appreciated by the general public, and the public in turn is pressing for more of both. The difficulty is that the research which is increasing the demand for service is moving ahead of the ability of our schools of medicine to develop and maintain the educational programs that can translate the resulting knowledge into the production of the kinds and numbers of the academic, research and practitioner personnel which both the present and future effectiveness of medicine requires. And unless corrective steps are taken, history will repeat itself and we will again be confronted with the pre-Flexner gap between what is known and what is taught.

Obviously it would be impossible, even unwise, to undertake to meet this problem by discontinuing or slowing down research and thus discouraging the improvement of service. Also, I am sure the problem cannot be solved by continuing to increase the content and length of the educational experience. Limitations of intellectual capacity preclude the addition of more curricular material without adding educational time, and limitations upon the human span of usefulness make it unreasonable to cut further into potential years of professional service.

The adjustment between the output of research, the performance of medical education, and the demands of service needs to develop a fresh approach. To accomplish this, we must shift away from those educational objectives that emphasize the acquisition of information and techniques under a spoon-feeding, tightly supervised situation toward objectives that can more effectively promote the ability to select, organize, and evaluate information and techniques, and this in a way that will stimulate as well as satisfy curiosity and also foster the kind of critical perception and sensitivity which the judgments of medicine as a learned profession will increasingly require. In this shift of objectives, the acquisition of information and techniques becomes a means to an end instead of an end in itself, and the manner of learning rather than what is learned receives the proper emphasis.

If we are to have the understanding necessary to the development of educational programs that can satisfy the implications in this shift of objectives, our concept of research that is basic to medicine must go beyond the laboratory, the hospital and clinic, the human environment and the economics, efficiency and effectiveness of medical care and include research that will increase our ability to select those teachers and learners most apt to succeed in the fast-moving medical scene and also research that will permit evaluation of the degree of objective attainment, particularly in terms of student accomplishment and the relative effectiveness of each combination of subject matter, teaching method, and practical frame of reference that is involved.

If the above statements are justified, perhaps this extension of research interest and activity can provide the framework within which all faculty people representing all of the discip lines important to medicine can be brought to develop more concern for and interest in the strictly pedagogic aspects of medical education.

So much for the qualitative considerations that I feel are important to the corrective steps of which I speak.

The most important corrective step of a quantitative nature is that our per-capita rate of physician production must be brought to a level that will keep pace with a rapidly growing population that is changing its composition in such a way as to require everincreasing amounts of health and medical care. The consideration of this problem can lend itself to rather simple arithmetic. But the task itself is not a simple one, for any way we may figure, we are forced to conclude that it is only the minimum goal that is capable of attainment. This means that if even our present ratio of physicians to population is to pertain, between now and 1975 our number of medical graduates must increase from eight to more than eleven thousand. Since the number who graduate from our schools of medicine is definitely limited by the number of students admitted to the first-year classes, all of which fill to capacity, I can say that in order to produce an annual increment of three thousand new physicians by 1975, we must by 1971 be admitting 3500 more medical freshmen than is presently the case. This is an input equal to that of 35 average-sized schools of medicine. While this input can be accomplished by various combinations of expanding existing enrollments and creating new schools, it will suffice for the purposes of this discussion to limit myself to a consideration of the particular contribution that can be made by the two-year school of medicine.

Speaking for the moment of our 83 schools that offer the full four-year medical course, I would have you know, now that the class of 1958 has reached its junior year, that vacancies have developed by a factor of nearly 900. Since transfers from the three schools currently offering the freshman and sophomore years can reduce this by only one hundred, so far as the two-year schools are concerned, the expansion of enrollments and the development of new units offer two very substantial answers to our shortage of physicians - and this in terms of considerable economy in money, faculty and facilities.

In doubling its number of freshman admissions, allowing for the usual academic attrition and physician deaths, Dartmouth's contribution to the physician manpower of this country will account for the care of an additional 25,000 people each year.

It is against this backdrop of qualitative and quantitative potential - new educational objectives, concepts and opportunities and expanding enrollments - that I see the challenges and opportunities for schools offering the first two years of the four-year medical curriculum. I cannot conceive of such programs giving satisfaction except within the framework of an environment that is academically strong and that is deeply rooted in the liberal arts and sciences on the one hand and graduate-level biology upon the other.

Because of nearly two centuries of honorable tradition in the liberal arts and sciences, because of recent advances into the graduate areas of biology, and because of the intimate availability of the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital and its practical frames of reference for clinical orientation and basic medical research, Dartmouth offers such an environment.

In my opinion the constellation of resources now present upon this campus - unfettered by any status quo, far removed from urban distraction, and closely associated with a hospital which, unlike its usual urban counterpart, offers academic opportunity free of the complications of clinical competition - provides Dartmouth with the opportunity, almost the mandate, to establish the two-year school as a significant part of this nation's system of medical education and this upon the basis of ideals and educational standards that are badly needed when we are struggling to keep pace with rapid medical progress. In fact, I do not think I exaggerate when I compare the importance of Dartmouth's opportunity of 1960 with that which confronted Johns Hopkins in 1893.

As a part of filling this destiny, with the elective work, the research opportunity and the free time Dartmouth can make available, it is important that many of its students go beyond simple preparation for the clinical years of some other school of medicine and seek competence in one of the basic medical disciplines - hopefully to the level of the master's degree, preferably to that of the Ph.D. With medicine constantly cutting deeper into and across more and more disciplines, the continued splitting of the resultant body of knowledge into separate and learnable parts is inevitable. But this body of knowledge is greater than the sum of its separate parts, and as a consequence, if proper coordination in the use of this knowledge is to pertain, individuals with the multidisciplinary experience herein implied will be the great hope of our future.

With a long tradition of superior students and superior faculty, with academic and research challenges and opportunities enhanced by the integration of the liberal arts and sciences with basic medicine and graduate biology, and with the decision to expand enrollment, this handsome and functional building will permit Dartmouth to go far in playing an increasingly important role in American medical education. We all recognize that a building must not become an end in itself, but we also recognize that a building can be a very necessary means to an end. I hope that this end marks two beginnings - the beginning of a new educational era for Dartmouth and the beginning of a new emphasis upon human biology for medicine. The President of Dartmouth and his deans and faculty should be the envy of the entire world of medical education, for I am sure they are embarking upon an experience that will be brimful of the satisfactions of accomplishment. May all go well!

Dr. Darley speaking during the cornerstoneceremony at the Medical Science Building.

"I do not think I exaggeratewhen I compare the importance of Dartmouth'sopportunity in 1960 with that whichconfronted Johns Hopkins in 1893."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMedicine's Moral Issues

October 1960 -

Feature

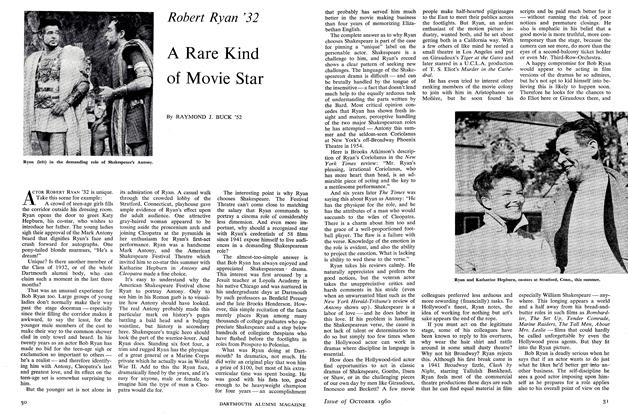

FeatureA Rare Kind of Movie Star

October 1960 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1960 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

October 1960 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, ERNEST H. GRISWOLD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

October 1960 By WESLEY H. BEATTIE, GEORGE N. FARRAND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1960 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER

Features

-

Feature

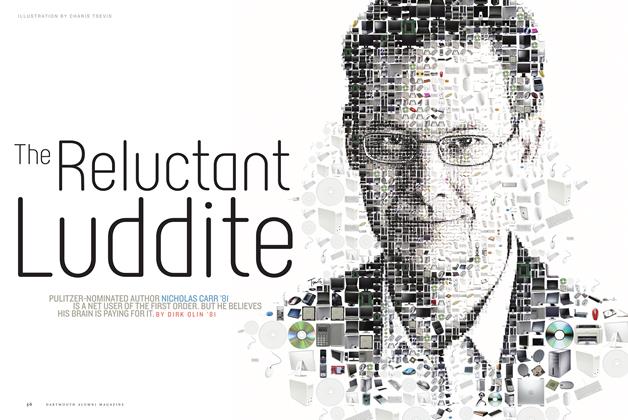

FeatureThe Reluctant Luddite

Sept/Oct 2011 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNo Script Required

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2017 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureHanover in the Ice Age

November 1957 By RICHARD J. LOUGEE '27 -

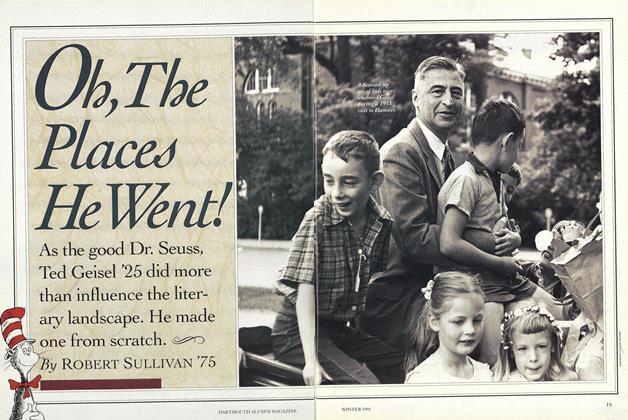

Cover Story

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureBONFIRE!

OCTOBER • 1986 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureProphet of Limits

NOVEMBER 1993 By Suzanne Spencer '93