WAH HOO WAH!

I disapprove of that particular cheer, and the meanspiritedness inherent in it, although I sometimes shouted it myself back in the early seventies. I disapprove of it now and haven't yelled it in years. But I set it up there in boldface capitals for a reason. I hope to suck in the Wahoo Yahoos who wouldn't otherwise read this here diatribe. (It was born a book review, but it's now destined, I fear, to be a diatribe.)

I need to sucker the Wahoo Tribe with this lure because* it seems, Yahoos like to listen only to their own voces clamantium in deserto. They turn a deaf ear whenever someone else savages their principles (term used loosely). We'll see this arrogant singlemindedness exhibited shortly by one of the tribe's current spear-carriers, the journalist (term used loosely) Charles J. Sykes. Sykes's recent book, The Hollow Men, purports to be an examination of Dartmouth's soul. Said soul is being probed these days by everyone from him to Harper's to The Boston Globe t0...we11, I guess, to me. Sykes's best shot at finding this essence the heart of Dartmouth is a shot indeed, a one-sided broadside that purports (there's that word again) to be objective and informed. It is neither. It is a diatribe, and I know a diatribe when I stumble upon one. It is so much a diatribe that it has caused this here essay to emerge from its book-review cocoon and fly forth as an answering diatribe. Sykes has, needless to say, got my dander up.

The Hollozu Men is one of four new books about higher education that I've read during the current publishing semester, and they supply variant examples of the current deep-thinking about college.

You may reasonably react: There are four new books about university life?

Trust me there are four and more including, of course, Dinesh D'Souza's provocative Illiberal Education (see the related story, page 24).

It's a phenomenon. While many of the authors contend we are experiencing the darkest age of American education, it is inarguably the golden age of The American Education Book. Everyone's into the act. Even the distinguished Pulitzer prizewinner Tracy Kidder suffered the indignity of squeezing himself into a little kid's seat to come up with Among Schoolchildren, one of the finest non-fiction books of the last couple of years.

And one of the bestselling: not an insubstantial point.

Blame Bloom. Blame Allan Bloom, who authored 1988's million-copy bestseller on higher education, The Closing of the AmericanMind. Blame him for the current spate of books on academe; blame him for all the folderol being printed in hopes of finding the fast buck; blame him that the wheat-books like Kidder's that are products of first-rate minds-risk being lost amongst so much chaff. Blame Bloom and his (Stephen) Kingly sales figures. It hardly matters that Bloom's book is said to be the least-read bestseller this side of Professor Hawking's A Short Historyof Time. Hardly matters? It matters not at all. Much of the book biz, 1991, isn't really about reading. It's about trends, marketing, sales. That education books should bloom like crabgrass throughout the land was assured by Bloom's mega-success. This plague of higher-ed books was as inevitable as "Darkman" following "Batman," as The Guys Next Door chasing The New Kids around the block. It's all part of the pseudo-sequel scenario, a staple of American life.

There! That diatribe done, I return to my original diatribe:

The Hollow Men is one of four new books about higher education that I've read during the current publishing semester, and they supply variant examples of the current think- ing on higher education. It is within this multi-hued tapestry that The Hollow Men is best considered. When it is set against bet- ter and more balanced books, its true colors shine glaringly. We can see The Hollow Men and its hollow mission for what they are.

Let's first paint in some background. Most suitable for this purpose is Page Smith's pretty good book, Killing the Spirit.

Smith, as it happens, is a Dartmouth alum ('40). He's also an accomplished educator and historian; his seven-volume People's History of the United States is widely praised.

In the first half of Killing the Spirit Smith puts his twin talents to work and presents a breezy, informative survey of the birth and middle age of American higher education.

His take on the founding fathers of the U.S. university is intriguing. We have the giants of society, tycoons like Hopkins, Rockefeller, and Carnegie, trying to outdo one another with their newest toys, their colleges. Out of this competition come some pretty fine schools, and no sooner were they founded than the squabbling began. About curriculum. About research versus teaching. About the relative significance of undergrads and post-grads. Still and all, the university, flush with the vitality of youth, burgeons throughout the late 1800s and looks like one more irresistably dynamic American force as the twentieth century begins.

That damned twentieth century. Bummer, as they say.

The signs of doom could have been seen, Smith seems to believe, in the unequivocal triumph of science over religion in American academe. He depicts Harvard philosophy professor William James, a seeker of truth and a dedicated teacher, as a symbol of the century's turn: a fallen hero, squeezed out by the secularists. A martyr, even.

Having taken a hundred pages to wet his whistle with entertaining history, Smith begins Chapter Nine this way: "There seems little doubt from the perspective of the present day that the introduction of the Ph.D. as the so-called union card of the profession was, if not a disaster, an unfortunate and retrograde step." Ahh... now we see where he's going. He gets there: tenured teachers who don't teach; bogus research performed as nothing more than busywork; professors who don't like their students and who want to bury their heads in their own books. In short, the killing of the spirit of education.

Although Smith's book is better before it takes this polemical turn, many of his arguments about contemporary higher education are persuasive. And they are highly pertinent to this "battle over Dartmouth's soul" that rages in 1991. A college the size and kind of ours would be well-advised, I think, to tread carefully as it listens to the siren song of the sexy, famous "Research University." It seems to me that within a damned fine undergraduate college of about Twin Peaks size, teaching should still be the primary thing. The current Dartmouth administra- tion seems to feel some alums don't think big enough. I would mildly state the obvious, that bigger isn't necessarily better, and that more isn't necessarily bigger. If more research means less time for teaching, and this transitively means more grad students teaching undergrads, how is this bigger? It's certainly not better.

So Smith's book, which is about half a good book, is wholly a cautionary tale for the Dartmouth family. Read it, think about it, enjoy it.

Read The Hollow Men too, and think about it. I did. And I must say, it's the least enjoyable, most infuriating book I've ever waded through.

It's tempting to compare the tones of Killing the Spirit and The Hollow Men. In Killing the Spirit, Smith writes most often as a chronicler. Sykes's usual mode is that of the investigator/critic. On occasions, both writers enter themselves into the narratives. This works better for Smith, who comes across as an expert witness rather than as someone who is simply bitching about his persecution by the liberal academic community. I'm referring here to Sykes's whining preface, wherein he digs into the Dartmouth Trustees' perceived effort to "cut the ground out" from under the crusading Sykes, as he storms the Hanover Plain. By contrast, Smith's personalized arguments have some weight. When he criticizes "the Cult of Dullness" that must be joined to get a Ph.D. these days-a cult that practices "oozy writing" and suffers from "oozy thinking," according to Smith-he comments as one who knows. He has been there. He has painfully attained that Ph.D.

Sykes, who once was a reporter for a Milwaukee newspaper and an editor for a Milwaukee magazine, has no such credentials. He doesn't try to write as a scholar, and I think that was a smart decision. As a journalist, he talks only to his friends, which is a cardinal sin of the profession. His procedure, as we say in the trade, has been to "fill in the quotes." It seems quite clear that he had an agenda going in. He never deviated a degree from his course.

This should surprise no one who has the necessary background information-mentioned nowhere between the covers of TheHollow Men-about the genesis of this book. Sykes is the author of 1988's Prof Scam, a better book than this, which also was about the "demise" of our universities. (A Prof Scam tidbit: "In the midst of this wasteland stands the American professor. Almost single-handedly, the professors... have destroyed the university as a center of learning and have desolated higher education." He should have called it The Waste Land, and got his Eliot theme rolling earlier.)

This man Sykes is a clear thinker, figured the good folks at the Ernest Martin Hopkins Institute when they finished reading Prof Scom. The EMHI, as you probably know, is Dartmouth's ever-helpful conservative conscience. It's sort of The Dartmouth Review's alumni association.

The Hopkins Institute must have felt it wasn't impacting the College sufficiently with its bulletins, and therefore offered Sykes $30,000 to do a prescribed task, which was to write The Hollow Men. Note carefully: his five-figure advance didn't come from a publishing house, in this case Regnery Gateway, but from a New York-based watchdog group cum political action committee. Writing The Hollow Men was Sykes's assignment from the Wahoo Yahoos. The Hopkins Institute put out a contract, literally and figuratively, on the College. Whereas Smith and others act as writers, Sykes acted as a hit man.

Too strong an assessment, you say? Look at it another way. Don't you think the Hopkins Institute would have been mighty distressed if Sykes had returned a report saying that, by and large, things were pretty good at Dartmouth?

They'd have gone nuclear on him.

"Ahhh, Challie... Challie, Challie. Ya let usdown, palo. Whad'we gonna do 'bout this, Challie? We gonna have to do sumpin'. Thirty G'sChallie. We needs results, for firty G's, yaknow?"

He'd have been fitted with cement shoes and dumped into the conservative think tank.

Of course, the Hopkins Institute has not reacted that way at all. The Institute finds Sykes's results more than satisfactory. He did his task and he did it loyally and well. In a recent issue, the Institute's bulletin refers to The Hollow Men as "The Great Book With The Objective Analyses of Your College's Curriculum." (The capitalization, which seems to know no rules, is the Institute's. I can't restrain myself from noting, perhaps too puckishly and with unseemly glee, that elsewhere in the same issue the Institute misspells Wah Hoo Wah.)

Any ways... the Institute is happy, and why shouldn't it be? Among the goods Sykes has delivered:

• professors who argue that a "lesbian continuum" can liberate women from "patriarchical concepts";

• safe-sex programs "chock full," as Sykes writes snidely, "of valuable infor- mation and helpful no- tions";

• a ridiculing of black and other minority-studies pro- grams;

• another recounting (just what everyone needed) of the strike, the Hovey mural debate, the shanties, Bill Cole, and — yes, again — the Indian symbol battle.

Here is Sykes, writing objectively, on the last item: "Although the symbol was an integral part of the school's tradition and wellloved by the college's loyal alumni, the trustees felt they must accommodate to the mood of the time." Well, good! Now it's finally been explained.

Of course, the focal point for much of Sykes's discussion is the war between the administration and The Dartmouth Review.

Re. the Review: as a journalist, I was happy to see another paper appear in Hanover, and I remain happy that The Review still exists. I really mean that; I'm not being disingenuous man being with half a brain in his head, I found Sykes's history of The Review galling. It read like a Review press release.

The Reviewers are portrayed here as either crusading journalists or, at the very worst, merry pranksters. The noted 1982 essay, "Dis Sho' Ain't No Jive, Bro'," was virulendy racist-just as right-winger Jack Kemp believed when he resigned from The Review's board of advisors after it was printed. Sykes, however, calls it a "satire," perhaps "a lapse in taste." The Review, to him, is "outrageous in its spoofs," as when it attacked the Gay Students Alliance by proposing College funding for the "Dartmouth Bestiality Association." In another case, a Review reporter called a College health officer, feigned distress about her sex life, got the administrator's sympathetic and graphic advice on tape, and published the transcript. The Review calls this journalism. Others would call it a setup, a sting. Stykes calls it an example of the paper's "penchant for mischief."

Sykes's decision to present a one-sided view is unfortunate for reasons besides the inherent one. It is unfortunate because beneath the bile and the bias lurk several valid criticisms. These criticisms, most of which have to do with curriculum, cry to be taken seriously. But how can they be, in this context?

Like Smith and most other reasonable people, Sykes has problems with phoney-baloney courses. Sykes cites "The Creative Process: Videotape," "The History of Clothing and Psychology of Dress," and "Sport and Society" among courses that trouble him. Since I can opine with confidence only upon the last one it's a gut, I would guess I'll not discuss his complaint further, except to say the whole question of what is taught and how it is taught is a very important question.

Unlike Smith, Sykes seems to think weird studies are something new. You want goofy class names? How about "Trends in Hosiery Advertising?" That course was taught in this country in the 19205, according to Smith, and this song was popular in the thirties:

I sing in praise of collegeOf M.A. 's and Ph. D.'s,But in pursuit of knowledgeWe are starving by degrees.

By the way, Dartmouth was presided over at that time by E.M. Hopkins '01 himself, the man who has been claimed by the College's conservative wing as a symbol of the golden age of education. Writes Smith, the historian: "There has been, so far as I have been able to determine, no golden age of teaching, certainly not at the better-known institutions." Sykes disagrees, writing in his chapter "The Hopkins Era" of a respectful faculty with superstars like David Lambuth, "the academic gentleman of the ancien regime," and Lewis Stilwell, "whose penchant for costumes. .. and vivid rhetorical imagery forever fixed both the form and the content of his lectures on his students' minds." I obviously never met Stilwell, but I'd hazard to match John Rassias's modern-day performance art against anyone's. And, right off the top of my head (and based solely upon personal experience), I would nominate Shewmaker of History, Starzinger of Govy, Bien of Comp Lit, and Hart of English as fine teachers. I learned a lot from them. They're all still on the job. There you have it: excellence in 1930, excellence in 1990. And no doubt a modicum of nonsense on the faculty of both eras as well.

I just had a disturbing thought as I scribbled that last paragraph. The Wahoo Yahoos, to whom politics is everything, are no doubt perusing my short list and figuring the political persuasion of each professor. The Yahoos are counting at least two and perhaps all of these teachers in their camp. (I know "at least two" because two are thanked by Sykes in his Hollow Men acknowledge-ments.) I'd like to stress something that might surprise the Yahoos: It doesn't matter. If Starzinger be a Marxist, a fascist or a radical feminist and I have no idea what he is he kept it out of the classroom. He taught, and there are others at Dartmouth who teach, with dedication. Those who don't, those who inflict their personal philosophies irrelevantly into their teachings, are in error. No doubt there are some of them on either extreme of the political spectrum. No doubt there were in Hopkins's day.

Now I promised this diatribe would deal with four books, and here I've gone on and on and I've dealt with only a pair. That's purposeful. The other two are very different from Smith's and Sykes's, and they concern us only tangentially.

One is morosely tided The University: AnOwner's Manual. Its author, Henry Rosovsky, who writes with surprising flair inside the book, would be well advised to enroll in Charles Sykes's "Titillating Titling 101." (But now that I think of it, I'm a bit surprised that Sykes didn't opt for the obvious Profli-Gate! -it's even sexier than Prof Scam for his first volume. And I still think Waste Land seems a good idea. Maybe for Volume Three.)

Rosovsky is of Harvard, and so is his book. The former dean of that school's faculty tells, anecdotally and well, of his good feeling for his university, and for much of higher education today. Rosovsy argues for reasonable standards that all students should be able to write well; that there should be a certain breadth to the curriculum but he does not shrink from asserting that the modern American university is a sounder institution than its forebear. At one point he takes on "our most severe critics" who, he senses, "have a distincdy right-wing political flavor."

"Let me make clear that I agree with many specific criticisms directed at us," Rosovsky writes. "Incoherent curricula, uncaring professors, 'gut courses' wherever they occur -upset me at least as much as they do our inquisitors. We do differ, I am sure, about the presumed frequency of these occurrences.

. .Much of the recent carping is based on nostalgia, an emotion which I do not share. About 40 years ago... there allegedly existed a Golden Age, and as John Buchan said with irony, civilization has been in decline ever since. In those wonderful days, core was core (and the 'gendeman's C' reigned supreme); adoring undergraduates sat at the feet of kindly mentors engaging in Socratic dialogue (the suggested image seems to be a 1930s Hollywood version of Oxford). These wonderful days were destroyed by the excesses of the 19605: dope, sex, grade inflation, contempt for the classics, and rock music.

"I like the university better today than 40 years ago."

He goes on to point out that it's simply not true that four decades past "we students -sat around our dormitories munching cookies and drinking milk while debating the merits of late Beethoven quartets."

I believed Rosovsky as I read that. And for the first time in all these pages of reading, I suddenly felt sympathy for Sykes and the other Wahoo Yahoos. For a moment, I wasn't angry with them. I saw them in a new light: as displaced Victorians, forced by Faust to constandy bear witness in this horribly unVictorian age. Perhaps, as they would no doubt argue, the present day is sad for us all, but certainly it's saddest for them. It's unremittingly sad for those who want to espy nothing but ivory-towered, arts-based, Christian, Mr. Chips-type universities on the educational horizon. Preferably all male, some would add. And preferably all white, others wouldn't dare to add.

Dear sad Victorians: you quest for something not to be found. It can't exist, it didn't exist yesterday, it never existed. You yearn for Camelot. Camelot was a myth. It was a terrific musical, and nothing more.

Which brings me in a round-about way to book number four. This is called, simply, Dartmouth. It's a coffee-table book edited by professors David Bradley '38 and Shelby Grantham, two who know and love the College well. They have chosen a host of lovely photographs and illustrations and have found scores of sometimes beautiful and always pertinent short writings about the institution.

This type of book often turns out to be about Camelots about mythical places but this one is more intelligent than that. This one seems to be about Dartmouth at its best, a place of much beauty, with an emotive pull, a place of dedication. Bradley and Grantham's is a good and true picture of the place.

The editors include in pictures and prose all the lovely green and white of the campus: Hanover at night at Christmastime, the last ember of a bonfire, the foliage always, always the foliage. And then there is a photo of Russell Sage Hall, banners draped from its windows, with an accompanying essay by Grantham on the tradition of protest at the College. She traces this from the Cambodia incidents through Watts up to South Africa, and the ugliness over the shanties. She has found a quote from John Sloan Dickey '29: "A college must learn as it goes and go as it learns and a healthy college being a somewhat ornery creature, all that learning and all that going are not likely to be in one direction."

Bradley and Grantham include the words to the alma mater, of course, and I applaud the way they do it. They reprint the current and correct words-"Dear old Dartmouth!" the words that all of us can share. Then they attribute them to Richard Hovey, class of 1885, as if Hovey would have written the song that way if he lived in our age.

Near the end of the book they include a comment that was made by Frank S. Streeter, class of 1884 and a 30-year trustee, to President Hopkins: "I'm not a religious man...but I think every man has to give worship to something bigger than himself, and Dartmouth College is a good enough religion for me."

I like that. It's a little pungent, and more than a mite sentimental, but I like it never-theless.

And it bothers me deeply, at this moment, that there are people reading this-people whom I might have suckered by planting that archaic cheer at the top of this diatribe -it bothers me deeply that there are doubtlessly some people who feel I have no right to align myself with anything pertaining to their patron saint, Hopkins.

As if it's their College exclusively, their Dear Old Dartmouth that existed once, and that will rise again.

As if it doesn't belong to each and every one of us, diverse as we are.

As if we all don't care for it just as deeply, and all want to see it get past this current strife.

As if we don't want it to be better each day, to be the best.

As if some of us love it less.

A diatribeuh, makethat reviewconcerningsome recentprobings ofDartmouth'spubliclyembattledsoul.

"Given theproclivitiesof the typicalacademicadministratorof the 19905,a seizure of anadministrationbuildingby militantradicalswould be simplyredundant." The Hollow Men, by journalistCharles Sykes

"Today's selectstudents knowso much less,are so muchmore cutoff from thetradition, areso much slackerintellectually,that theymake theirpredecessorslook likeprodigiesof culture." The Closing of the American Mind, byAllan Bloom,classicist atthe Universityof Chicago

"I like theuniversitybetter todaythan 40 yearsago, and thatmay be thereason for myoptimism." The University: An Owner's Manual, byHenryRosovsky,former deanof the Facultyof Arts andSciences atHarvard

Harvard's Rosovsky makesa lonely defense of highereducation. "To be positiveis never very popular inintellectual circles," he says.

The academy's downfall beganwhen the secularists bumped asideWilliam James and his philosophy,according to Page Smith.

"Thefacultiesat the eliteuniversities(and, increasingly, atthose lesserinstitutionsbent on apingthem) are infullflight fromteaching. Thisis certainlynot a newdevelopment. Ithas been goingon, in varyingdegrees, sincethe rise ofthe modernuniversity. " Killing the Spirit, by Page Smith'40, historian

"Behind thedesigners andthe builders,barely noticed inthe long, coolshadows, areDartmouth'sdreamers: thepoets, themusicians.They formedour impulsesinto words. Theygave singingto our spirits.Miraculously." Dartmouth, byDavid Bradley'38 and ShelbyGrantham

"If facompellingreasons, suchas a strongexpression fromthe governingboard, thepresident musttake a positionagainst foolsand nonsense,it must becarefullycrafted afterconsultationwith universitylawyers andthorough staffanalysis andreview." A Primer for University Presidents, by Peter T.Flawn,former presidentof the Universityof Texas

Sports Illustrated editor and diatribalist RobertSullivan's last article for the Alumni Magazinewas on Corey Ford, in the September issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

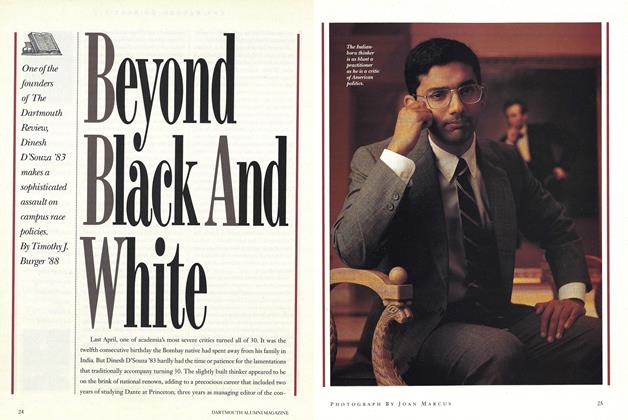

FeatureBeyond Black And White

June 1991 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Feature

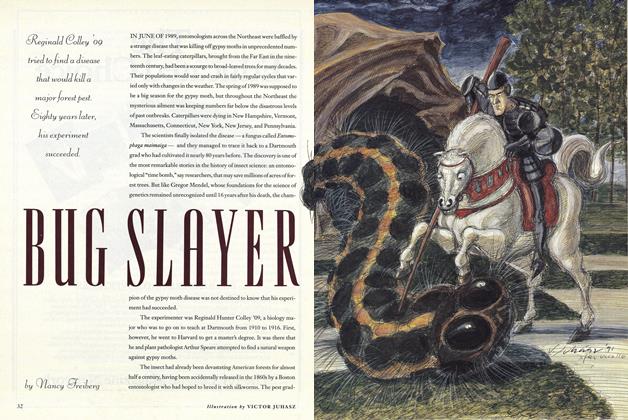

FeatureBUG SLAYER

June 1991 By Nancy Freiberg -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

June 1991 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleCOMPUTING AND THE RING OF INVISIBILITY

June 1991 By Professor James Moor, Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Alumni Awards

June 1991 -

Article

ArticleORIGINALS AND COPIES

June 1991 By James O. Freedman

Robert Sullivan '75

-

Cover Story

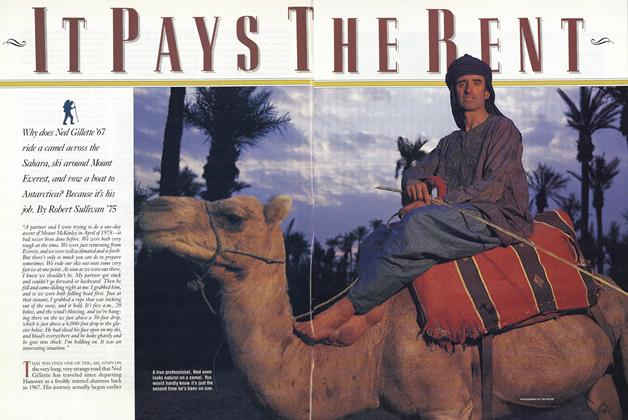

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

APRIL 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

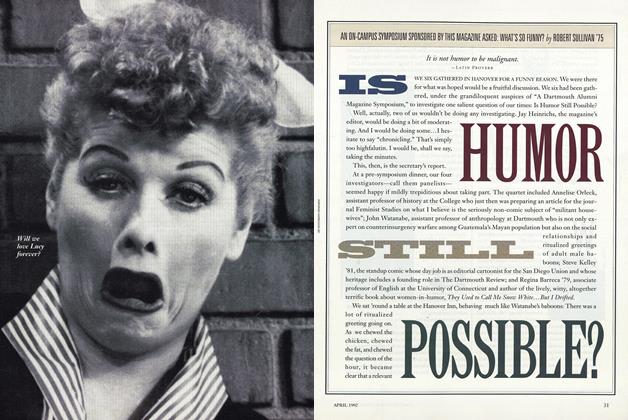

Cover StoryIS HUMOR STILL POSSIBLE?

APRIL 1992 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

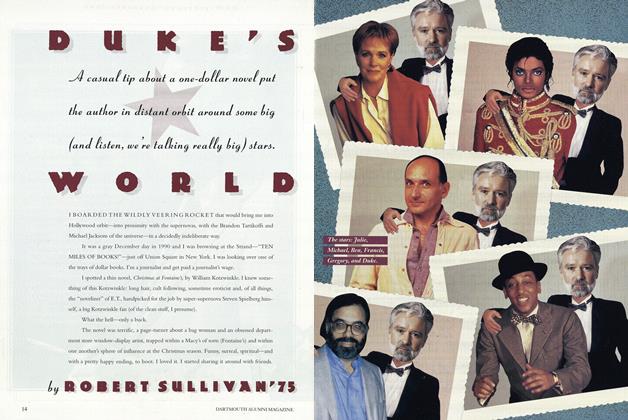

FeatureDUKE'S WORLD

February 1993 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Cover Story

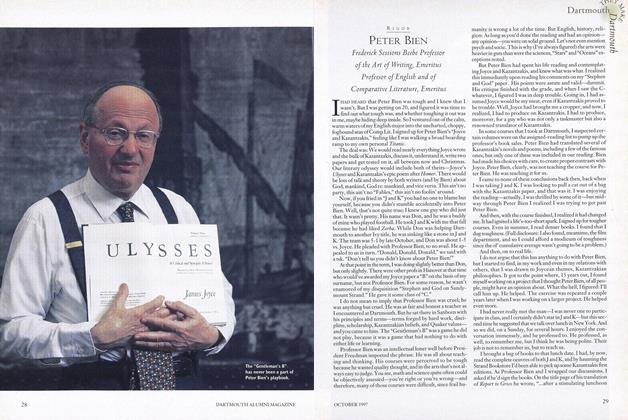

Cover StoryPeter Bien

OCTOBER 1997 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe New New York

Jan/Feb 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Cover Story

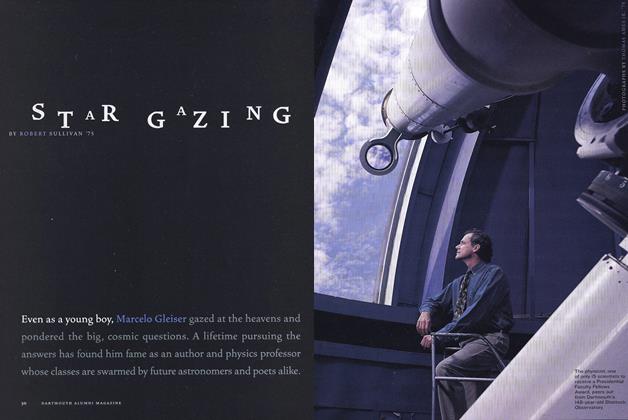

Cover StoryStar Gazing

July/Aug 2003 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFourteen Gained — Three to Go

MAY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureOnward and Upward with '68

NOVEMBER 1964 -

FEATURE

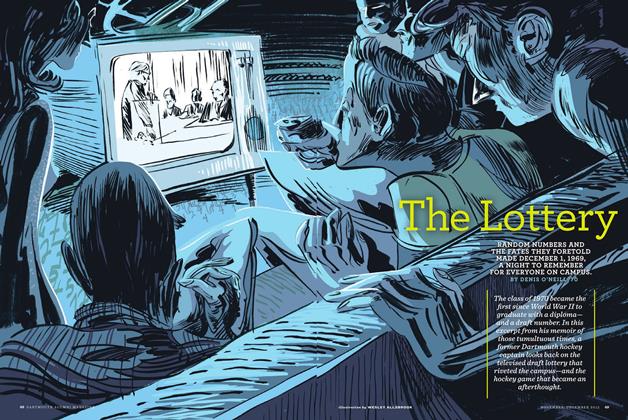

FEATUREThe Lottery

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By DENIS O’NEILL ’70 -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND REMEMBRANCE

December 1995 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureAn Environmental B

Winter 1993 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

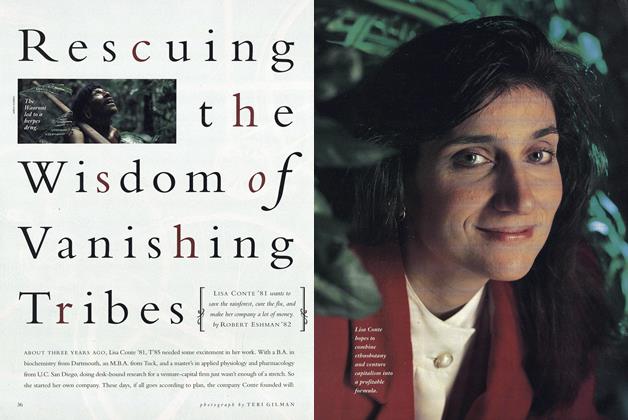

FeatureRescuing the Wisdom of Vanishing Tribes

June 1993 By Robert Eshman '82