ONE of the great events in the recent life of the College was the Dartmouth Convocation on Great Issues in the Anglo-Canadian-American Community, held in September 1957 to coincide with the tenth anniversary of the widely known Great Issues Course, and to mark the launching of the College's campaign to raise $17,000,000 as the first major step toward fulfilling its 1969 Bicentennial goals.

Last month, for the three-day period September 8 to 10, the College and the Dartmouth Medical School jointly sponsored a second Great Issues Convocation, this time on the theme of "Conscience in Modern Medicine." The assemblage of distinguished scientists, physicians, authors and statesmen who were participants and the many hundreds of alumni and others who were their audience marked the "refounding" of the Dartmouth Medical School, which last month occupied the first completed unit of its new Medical Science Building and also made additional advances in an expanded program of medical education anchored in the basic sciences.

The Convocation provided an appropriate occasion for the gathering in Hanover of the Dartmouth men who are serving as national and regional leaders in the campaign to raise the $5,000,000 still needed to carry out the Medical School program. Over $5,000,000 has already been contributed, mainly in the form of large grants from private foundations and the U. S. Public Health Service, who see in Dartmouth's "prototype" two-year school one of the answers to the country's growing need of more physicians and medical scientists.

The moral and social questions that these doctors and scientists will find pressing in on them more and more in the years ahead, as medical science and technology advance at a rapid pace and the world's population grows alarmingly, were the central theme that the Great Issues Convocation tackled for three days in Hanover. "Medical science only tells us how to do things, not what we should do among all the things we can now do and the many more we will be able to do in the near future - and the choice as to what we do will have to be the responsibility not of the doctors and scientists but of all society, because the questions to be answered are moral questions." This was the idea that pervaded a wide variety of discussions that ranged over such topics as air pollution, man-made radiation, food additives, increasing longevity, the so-called "statistical morality" of today,' new techniques of blueprinted human reproduction, man's breaching of the age-old dam of natural selection, birth control, brain washing, the control of man's social behavior through behavioral science, drugs that influence the mind, and psychotherapeutic procedures to limit man's dangerous rages.

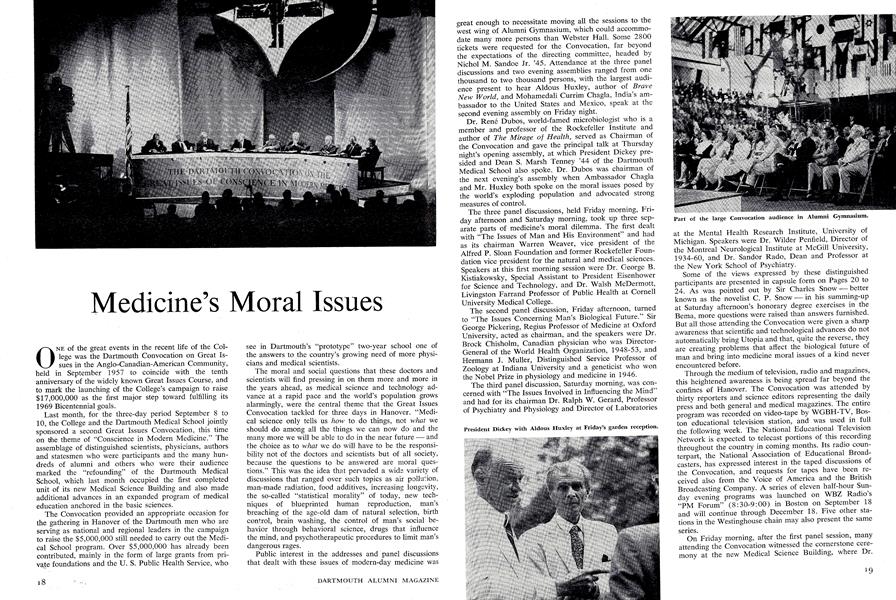

Public interest in the addresses and panel discussions that dealt with these issues of modern-day medicine was great enough to necessitate moving all the sessions to the west wing of Alumni Gymnasium, which could accommodate many more persons than Webster Hall. Some 2800 tickets were requested for the Convocation, far beyond the expectations of the directing committee, headed by Nichol M. Sandoe Jr. '45. Attendance at the three panel discussions and two evening assemblies ranged from one thousand to two thousand persons, with the largest audience present to hear Aldous Huxley, author of BraveNew World, and Mohamedali Currim Chagla, India's ambassador to the United States and Mexico, speak at the second evening assembly on Friday night.

Dr. Rene Dubos, world-famed microbiologist who is a member and professor of the Rockefeller Institute and author of The Mirage of Health, served as Chairman of the Convocation and gave the principal talk at Thursday night's opening assembly, at which President Dickey presided and Dean S. Marsh Tenney '44 of the Dartmouth Medical School also spoke. Dr. Dubos was chairman of the next evening's assembly when Ambassador Chagla and Mr. Huxley both spoke on the moral issues posed by the world's exploding population and advocated strong measures of control.

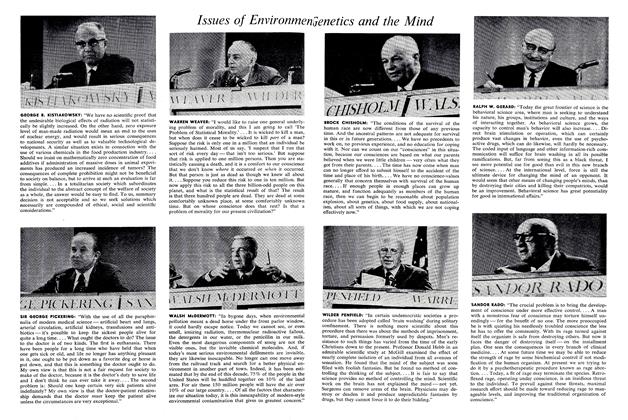

The three panel discussions, held Friday morning, Friday afternoon and Saturday morning, took up three separate parts of medicine's moral dilemma. The first dealt with "The Issues of Man and His Environment" and had as its chairman Warren Weaver, vice president of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and former Rockefeller Foundation vice president for the natural and medical sciences. Speakers at this first morning session were Dr. George B. Kistiakowsky, Special Assistant to President Eisenhower for Science and Technology, and Dr. Walsh McDermott, Livingston Farrand Professor of Public Health at Cornell University Medical College.

The second panel discussion, Friday afternoon, turned to "The Issues Concerning Man's Biological Future." Sir George Pickering, Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford University, acted as chairman, and the speakers were Dr. Brock Chisholm, Canadian physician who was DirectorGeneral of the World Health Organization, 1948-53, and Hermann J. Muller, Distinguished Service Professor of Zoology at Indiana University and a geneticist who won the Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine in 1946.

The third panel discussion, Saturday morning, was concerned with "The Issues Involved in Influencing the Mind" and had for its chairman Dr. Ralph W. Gerard, Professor of Psychiatry and Physiology and Director of Laboratories at the Mental Health Research Institute, University of Michigan. Speakers were Dr. Wilder Penfield, Director of the Montreal Neurological Institute at McGill University, 1934-60, and Dr. Sandor Rado, Dean and Professor at the New York School of Psychiatry.

Some of the views expressed by these distinguished participants are presented in capsule form on Pages 20 to 24. As was pointed out by Sir Charles Snow - better known as the novelist C. P. Snow - in his summing-up at Saturday afternoon's honorary degree exercises in the Bema, more questions were raised than answers furnished. But all those attending the Convocation were given a sharp awareness that scientific and technological advances do not automatically bring Utopia and that, quite the reverse, they are creating problems that affect the biological future of man and bring into medicine moral issues of a kind never encountered before.

Through the medium of television, radio and magazines, this heightened awareness is being spread far beyond the confines of Hanover. The Convocation was attended by thirty reporters and science editors representing the daily press and both general and medical magazines. The entire program was recorded on video-tape by WGBH-TV, Boston educational television station, and was used in full the following week. The National Educational Television Network is expected to telecast portions of this recording throughout the country in coming months. Its radio counterpart, the National Association of Educational Broadcasters, has expressed interest in the taped discussions of the Convocation, and requests for tapes have been received also from the Voice of America and the British Broadcasting Company. A series of eleven half-hour Sunday evening programs was launched on WBZ Radios "PM Forum" (8:30-9:00) in Boston on September 18 and will continue through December 18. Five other stations in the Westinghouse chain may also present the same series.

On Friday morning, after the first panel session, many attending the Convocation witnessed the cornerstone mony at the new Medical Science Building, where Dr. Ward Darley, executive director of the Association of American Medical Colleges, delivered the main address (see Pages 24 and 25). That afternoon there was a chance to meet the Convocation's guest participants at a garden reception at the President's House. Guided tours of the old and new medical plants were available, and among special exhibits was one in College Hall depicting the educational program of the Medical School and another in Baker Library dealing with history and personalities of the School, the third oldest in continuous service in the country.

As Dean Tenney pointed out in his remarks at the cornerstone ceremony, the Convocation, quite by chance, was held just 150 years after Dr. Nathan Smith, founder of Dartmouth Medical School, had planned and seen realized the building that is still standing and is known as the Old Medical Building. It now has the dubious distinction of being the oldest medical building still in active use for medical purposes in the United States. The contrast between Nathan Smith's original building and the new seven-story Medical Science Building is enormous. And equally immense is the difference between the early faculty and the present staff, which includes some fifty Hitchcock Hospital doctors as the clinical faculty and forty medical scientists as the full-time faculty.

Among the large number of Dartmouth College and Medical School alumni in Hanover for the Convocation were John Brown Cook '29 of New Haven and Dr. John L. Norris '25 of Rochester, N. Y., co-chairmen of the Dartmouth Medical School Campaign. Dr. Waltman Walters '17 of the Mayo Clinic, honorary chairman, was also present. These three leaders, in company with three of the four honorary vice-chairmen - Dr. Frank Meleney '10, Dr. Arthur Ruggles '02 and Dr. Frederick Sanborn '99, met with other members of the campaign executive committee Thursday afternoon. Present were Dr. John P. Bowler '15, Charles E. Brundage '16, Edward M. Cavaney of Hanover, Dr. Sven M. Gundersen of the faculty, Dr. Ralph W. Hunter '31, Prof. Russell R. Larmon '19, Basil O'Connor '12, Walter Paine of Norwich, Dr. Curtis C. Tripp '18, and Dr. Robert J. Weiss of the faculty. Other executive committee members are: Rollin H. Sturtevant '12, honorary vice-chairman; James C. Chilcott '2O, Dr. Emerson Day '34, Charles Gilman, William H. Lang '33, Richard D. Lombard '53, Thomas C. Murdough '26, Ralph E. Samuel '13, and John C. Wood '22.

During the weekend meetings were held by two other development groups: the National Committee for the Development of the Dartmouth Medical School and the area chairmen for the Medical School Campaign. For all these leaders the Convocation and the sight of the nearly completed Medical Science Building were a great stimulus for the fund work ahead.

Convocation Chairman

DR. RENE DUBOS, the Convocation chairman, is shown above (center) with C. P. Snow and Dr. Penfield at the close of a panel discussion. Following are some of the views expressed in his address at the opening assembly:

"One could believe that the increasingly rapid development of science will soon lead us to Medical Utopia. In reality, however, the greatest difficulties to the achievement of health in the modern world will come not from lack of scientific knowledge but from social limitations that will create great problems of conscience for the medical community. . . .

"As a group we are not emotionally prepared to act toward problems that seem remote in time. Air pollution is such that it affects health not necessarily this year, next year, or in ten years, but the health of the community in twenty years. It is extremely difficult to enlist public interest, even the interest of scientists, in such long-range problems. . . . How much of economic prosperity and of conveniences of life is society willing to sacrifice to prevent lung cancer, emphysema, and chronic bronchitis that will become apparent only in the future? How can we balance the value of human suffering that will occur in some undetermined future against the effectiveness of social performance of a community today? . . .

"The problem is no longer the scientific one of how to produce vaccines, but rather the social one of deciding which vaccines should be produced. . . . Should emphasis be placed on diseases which are fatal or crippling, but affect only small numbers of individuals, like poliomyelitis? Or should priority be given to ailments of the upper respiratory tract, rather mild and self-limited, but of great economic importance because they affect a large percentage of the population and disrupt industrial production and other activities? . . .

"There are now many techniques available for postponing death in every age group and for most any type of disease. . . . Consider the problem of prolonging the life of an aged and ailing person. To what extent can we afford to prolong biological life in individuals who cannot derive either profit or pleasure from existence, and whose survival creates painful burdens for the community? . . .

"Experimental and clinical science can solve the biological aspects of almost any medical problem, but in practically all cases the solution will be very costly in money, and especially in terms of specialized talent. While it is possible in theory to deal with all the new health problems that will be created by our rapidly changing social and technological order, many possible measures of control will have to be neglected in practice because of the limitations of economic and human resources. Hence there will have to be choices, and these choices are not to be left to the physicians. They will have to be made by society as a whole, because they will involve value judgments."

Some of the Things the Panelists Said...

Issues of Environment Genetics and the Mind

Part of the large Convocation audience in Alumni Gymnasium.

ALDOUS HUXLEY: "What are the humane and rational substitutes for Nature's methods of dealing with overpopulation? . . . Two courses are open to us. Both must be pursued simultaneously. (1) Increase production of food and industrial goods. This is feasible, but only if vast amounts of capital are forthcoming and only if all available knowledge, intelligence and good will are mobilized. . . . (2) Efforts to increase production must go hand in hand with efforts to bring birth rates into balance with death rates. Death control is easy and cheap; birth control is expensive and difficult, for it is a multiple problem—chemical, medical, sociological, psychological, educational and, in some quarters, theological. . . . Though a rational population policy, internationally agreed upon, would not bring an immediate solution, it must nevertheless be adopted. If it is not, our grandchildren and great-grandchildren will be in for the worst time of troubles ever faced by the human race."

SIR CHARLES SNOW: "I'm inclined to think that the reverse, or obverse, of statistical morality is technological cynicism. . . . It's growing upon us day after day; the actual tone of voice in which we discuss these problems is not the tone in which decent men should discuss them. We do it in a sort of dry, flip way, which means we are not immersed, we're not using the extended imagination. . . . Now, as to what we should do. It is clearly not easy. It seems to me that the first thing is to tell the truth. That is the first duty of all scientists - it's a built-in feature of science itself, and one which makes me feel that it's wrong to say that 'science is ethically neutral.'. . . The second thing is not to leave it to society in quite as easy a fashion as some of my wiser friends would suggest. . . . We happen to know just a little more, to be a little more articulate. We happen, if we're not very bad men indeed, to have our consciences a little sorer, because this statistical morality is something we have to live with."

GEORGE B. KISTIAKOWSKY: "We have no scientific proof that the undesirable biological effects of radiation will not statistically be slightly increased. On the other hand, zero exposure level of man-made radiation would mean an end to the uses of nuclear energy, and would result in serious consequences to national security as well as to valuable technological developments. A similar situation exists in connection with the use of various chemicals in the food production industry. . . . Should we insist on mathematically zero concentration of food additives if administration of massive doses in animal experiments has produced an increased incidence of tumors? The consequences of complete prohibition might not be beneficial to society on balance, but to arrive at such an evaluation is far from simple. . . . In a totalitarian society which subordinates the individual to the abstract concept of the welfare of society as a whole, the answer would be easy to find. To us, summary decision is not acceptable and so we seek solutions which necessarily are compounded of ethical, social and scientific considerations."

SIR GEORGE PICKERING: "With the use of all the parapher- nalia of modem medical science - artificial heart and lungs, arterial circulation, artificial kidneys, transfusions and antibiotics it's possible to keep the sickest people alive for quite a long time. . . . What ought the doctors to do? The issue to the doctor is of two kinds. The first is euthanasia. There have been people for a long time who have held that when one gets sick or old, and life no longer has anything pleasant in it, one ought to be put down as a favorite dog or horse is put down, and that this is something the doctor ought to do. My own view is that this is not a fair request for society to make of the doctor, because it is the doctor's duty to save life and I don't think he can ever take it away. . . . The second problem is: Should one keep certain very sick patients alive indefinitely? My own view is that the doctor-patient relationship demands that the doctor must keep the patient alive unless the circumstances are very exceptional."

WARREN WEAVER: "I would like to raise one general underlying problem of morality, and this I am going to call 'The Problem of Statistical Morality.'. . . It is wicked to kill a man, but when does it cease to be wicked to kill part of a man? Suppose the risk is only one in a million that an individual be seriously harmed. Most of us say, 'I suspect that I run that sort of risk every day - that isn't too serious.' But suppose that risk is applied to one million persons. Then you are statistically causing a death, and it is a comfort to our conscience that we don't know where it occurred or when it occurred. But that person is just as dead as though we knew all about it. . . . Suppose you reduce this risk to one in ten million. But now apply this risk to all the three billion-odd people on this planet, and what is the statistical result of that? The result is that three hundred people are dead. They are dead at some comfortably unknown place, at some comfortably unknown time. But on whose conscience does that rest? Is that a problem of morality for our present civilization?"

WALSH McDERMOTT: "In bygone days, when environmental pollution meant a dead horse under the front parlor window, it could hardly escape notice. Today we cannot see, or even smell, ionizing radiation, thermonuclear radioactive fallout, the detergents in our water, or the penicillin in our milk. Even the most dangerous components of smog are not the visible ones, but the invisible chemical molecules. And, if today's most serious environmental defilements are invisible, they are likewise inescapable. No longer can one move away from the railroad track and search for a better physical environment in another part of town. Indeed, it has been esti- mated that by the end of this decade, 75% of the people in the United States will be huddled together on 10% of the land area. For air these 150 million people will have the air over 10% of our large country. . . . Of all the factors that characterize our situation today, it is this inescapability of modern-style environmental contamination that gives us greatest concern:"

BROCK CHISHOLM: "The conditions of the survival of the human race are now different from those of any previous time. And the ancestral patterns are not adequate for survival in this or in future generations. . . . We have no precedents to work on, no previous experience, and no education for coping with it. Nor can we count on our "consciences" in this situation, because our consciences are based on what our parents believed when we were little children - very often what they got from their parents. . . . The time has now come when man can no longer afford to submit himself to the accident of the time and place of his birth. . . . We have no conscience-values generally that concern themselves with survival of the human race. . . . If enough people in enough places can grow up mature, and function adequately as members of the human race, then we can begin to be reasonable about population explosion, about genetics, about food supply, about nationalism, about all sorts of things, with which we are not coping effectively now."

WILDER PENFIELD: "In certain undemocratic societies a procedure has been adopted called 'brain washing' during solitary confinement. There is nothing more scientific about this procedure than there was about the methods of imprisonment, torture, and persuasion formerly used by despots. Men's resistance to such things has varied from the time of the early Christians down to the present. Professor Donald Hebb in an admirable scientific study at McGill examined the effect of nearly complete isolation of an individual from all avenues of sensation. He found that the mind of the subject was soon filled with foolish fantasies. But he found no method of controlling the thinking of the subject. . . . It is fair to say that science provides no method of controlling the mind. Scientific work on the brain has not explained the mind - not yet. Surgeons can remove areas of the brain. Physicians may destroy or deaden it and produce unpredictable fantasies by drugs, but they cannot force it to do their bidding."

RALPH W. GERARD: "Today the great frontier of science is the behavioral science area, where man is seeking to understand his nature, his groups, institutions and culture, and the ways of interacting together. As behavioral science grows, the capacity to control man's behavior will also increase. . . . Direct brain stimulation or operation, which can certainly produce vast changes in behavior, even the use of psychoactive drugs, which can do likewise, will hardly be necessary. The coded input of language and other information-rich communication will suffice for brain washing in all its possible ramifications. But, far from seeing this as a black threat, I see more potential use for good than evil in this new branch of science. . . . At the international level, force is still the ultimate device for changing the mind of an opponent. It would seem that other means of changing people's minds, than by destroying their cities and killing their compatriots, would be an improvement. Behavioral science has great potentiality for good in international affairs."

SANDOR RADO: "The crucial problem is to bring the development of conscience under more effective control. . . . A man with a monstrous fear of conscience may torture himself unendingly — for the benefit of no one. The more preoccupied he is with quieting his needlessly troubled conscience the less he has to offer the community. With its rage turned against itself the organism is safe from destroying others. But now it faces the danger of destroying itself - on the installment plan. One sees the consequences in every branch of clinical medicine. . . . At some future time we may be able to reduce the strength of rage by some biochemical control if not modification of the human organism. At present we are trying to do it by a psychotherapeutic procedure known as rage abortion. . . . Today, a fit of rage may terminate the species. Retroflexed rage, operating under conscience, is an insidious threat to the individual. To prevail against these threats, maximal research effort should be made toward reducing rage to manageable levels, and improving the traditional organization of conscience."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

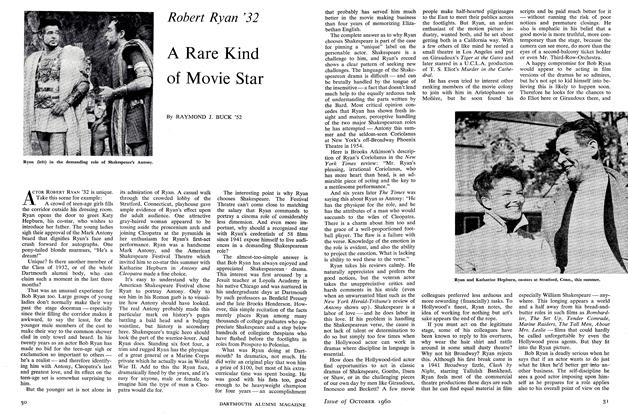

FeatureA Rare Kind of Movie Star

October 1960 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Medical Opportunity

October 1960 By WARD DARLEY -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1960 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

October 1960 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, ERNEST H. GRISWOLD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

October 1960 By WESLEY H. BEATTIE, GEORGE N. FARRAND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1960 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER

Features

-

Feature

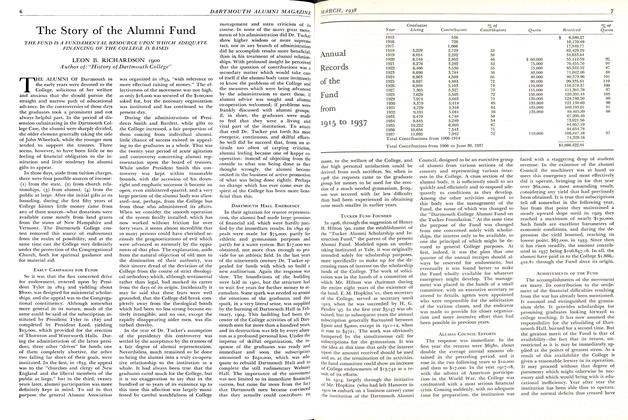

FeatureAnnual Records of the Fund from 1916 to 1937

March 1938 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChargé d'Affaires

April 1981 -

Feature

FeatureThe Diminishing Citizen

July 1962 By BASIL O'CONNOR '12 -

Feature

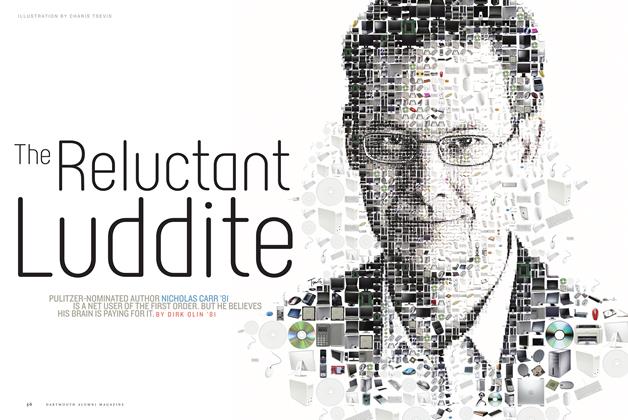

FeatureThe Reluctant Luddite

Sept/Oct 2011 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Merlino Miss

OCTOBER 1994 By George Anastasia -

Feature

FeatureNew Edition of Webster Papers

MARCH 1968 By John Hurd '21