THE ISSUES CONCERNING MAN'S BIOLOGICALFUTURE

Chairman: SIR GEORGE PICKERINGREGIUS PROFESSOR OF MEDICINE, OXFORD UNIVERSITY

WE propose this afternoon to discuss with you three of the more important problems concerning "Man's Biological Future," and these problems arise in two ways. First, because of what we've already done and second, what we might do. Now, what we've already done has posed two new problems - one, an enormously large one, and one, a rather small one.

The enormously large one is concerned with the future size of the population of the world. As you know, populations have been in balance with the natural enemies of man - disease - over countless years and in some of the large centers of population, owing to the application of medical and scientific knowledge, the death rate has suddenly fallen without a corresponding fall in birth rates, with the result that the population of the world is likely to increase to such an extent that within perhaps the time of our grandchildren the population may outrun its food supply.

The second problem arising out of what we've done is of puny proportions as compared with the last, but it is an issue which particularly concerns medicine: "Should we keep certain extremely sick people alive indefinitely?"

With the use of all the paraphernalia of modern medical science it's possible to keep nearly anybody alive for an indefinite period; with the use of artificial respiration, artificial circulation, artificial kidneys, transfusion and antibiotics it's possible to keep the sickest people alive for quite a long time. Now this has presented society with certain new problems which society, meaning you, find disturbing. What ought the doctors to do? The issue to the doctor is of two kinds. The first is euthanasia. As you know this is an ancient problem and for a long time there have been people who have held that when one gets sick or old, and life no longer has anything pleasant in it, one ought to be put down as a favorite dog or a favorite horse is put down, and that this is one of the things that the doctor ought to do. My own view is that this is not a fair request for society to make of the doctor, because it is the doctor's duty to save life and I don't think he can ever take it.

The second problem is: Should one keep certain very sick patients alive indefinitely? Now this, I think, is a different issue. My own view is that the doctor-patient relationship demands that the doctor must keep the patient alive unless the circumstances are very exceptional. I can illustrate what I mean by two examples: About two years ago a young woman was admitted to the hospital in which I worked, after an automobile accident, and she was unconscious. She would have died had it not been for artificial respiration, which kept her alive. Two years later she is still alive, but she is unconscious and it's doubtful whether she will ever regain consciousness so long as she lives. Now, I have no doubt that it is our duty to keep that patient alive, because the discipline of a hospital demands that this should be done, and it's not doing anybody any harm.

Another example: A distinguished scientist whom I knew very well had a series of strokes. He couldn't walk; he couldn't talk; he was bed-ridden; he had to be fed, and he was incompetent both in the urine and feces; and he was looked after by his devoted wife, who was unable to go out of the house the last year of his life. The last time I went to see him he was breathing at 40 per minute and I knew that he had bronchial pneumonia. Should I have informed his physician so that he could give him antibiotics? This was a question that I had to settle with my own conscience. I couldn't ask his wife. What I did was to say nothing, and four days later that man died. And that I think was right, because this was ruining a devoted woman's life.

Now, a problem of quite a different order is what we ought to do in the future about trying to improve the human race, and when I talk about "the human race" I'm not talking about one race against another - for instance, an Arab against a Chinaman - because I think that kind of question has led to so much trouble in the past that we ought to keep off it! But what I mean is: Ought we to be breeding children as we breed dogs and race horses and within our community?

This became an exciting problem about a century ago when the acceptance of the evolution theory opened people's eyes to the possibility of evolving better human beings. And it particularly excited Francis Galton who was a cousin of Darwin, and whose observations of man had convinced him of the reality of human inheritance. Galton thought that it was our duty to breed better human beings and he suggested that the State should make awards to young men and young women to enable them to marry and produce children. In other words, that the State ought to run a sort of stud farm with selected young men and young women - selected, of course, on their genetic characteristics, to produce better babies.

This problem has received new urgency because of new knowledge obtained in genetics and because of new knowledge of reproductive technique. If I may again use the analogy of animal husbandry - because after all, if we detach ourselves, that is what this problem is - when we realize that it is possible to collect sperm from a bull and to store these and transport them all over the world, and to have progeny from that bull by artificial insemination, one realizes what enormous possibilities there are in terms of the human race. There obviously are social consequences of all that, but I'm not going to follow that up. I'm now going to ask the Panel to take over and I shall call first on Dr. Chisholm.

Speaker: BROCK CHISHOLMDIRECTOR-GENERAL OF THE WORLD HEALTHORGANIZATION, 1948-1953

I THINK it might be most profitable if I spent the minutes at my disposal in talking about conscience, which is the basis of our discussions here - "The Great Issues of Conscience in Modern Medicine." Most people tend to take for granted that they know what they mean by "conscience" and that "conscience" is in fact what they mean, which is not necessarily true.

For most people conscience is something that is not questionable - that gives an answer without thought - that is a feeling, which produces in relation to certain ideas, or certain forms of behavior, a feeling of virtue or, on the other hand, a feeling of guilt or shame. For most people this voice, which is internal, is accepted as ultimate authority, their basic authority. It occurs to relatively few people that the language in which conscience speaks is for each of us entirely accidental. "It is determined by the family in which we were brought up and by the attitudes which were about us when we were small; and largely its development is finished by about six or seven or possibly eight years of age. Relatively few people of the human race, generally, do undertake to help their conscience to continue to grow and develop toward maturity. Conscience for most people, then, is simply whatever they believed when they were small children.

All through the development of the human race, consciences have been valuable. They're a short-cut. They make it unnecessary to think about a great many things and, if the attitudes of the parents who inculcated attitudes in their children were sound at that time and continue to be sound, then conscience can be very valuable. But in general, consciences are not necessarily to be relied on, unless one has examined one's own conscience very carefully in relation to every conceivable situation and adjudged it reliable in terms of the evidence and the present situation, and not in terms of the attitude of the ancestors, which may or may not continue to be valid in changed circumstances.

There is considerable authority now in support of such an attitude. For instance, in the Constitution of the World Health Organization there are two statements that are relevant to this discussion. One is the definition of the word health. This statement, by the way, has been subscribed to by some ninetytwo governments on behalf of practically all the people in the world, so that it is a highly authoritative statement defining the word "health." "Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity." This is an important statement because it indicates the requirement placed on individuals now in this generation that did not exist in previous generations. No one was expected to be socially healthy in the past.

There's also a further relevant statement about children. 'The healthy development of the child (healthy meaning physically, mentally and socially) is of basic importance. The ability to live harmoniously in a changing total environment is essential to such development." This means that generations from now one must be able to live in ways appropriate to new circumstances, whether or not those circumstances were known to his parents or any of his ancestors. And this is important because we are now trying to live in circumstances totally unknown to any of our ancestors in the past. The conditions of survival of the human race are now different from those of any previous time. And the ancestral patterns, we can be quite confident, are not adequate for survival in this or in future generations, because our ancestral attitudes inevitably and invariably led to warfare, which now for the first time in human history has become synonymous with suicide. This is new in the world! A situation totally unknown until just the last few years. We have no precedents to work on, no previous experience of this situation, and we have no education for coping with it. Nor can we count on our consciences in reference to this situation, because our consciences are based on what our parents believed when we were little children, very often what they got from their parents. It would seem that the time has now come when man can no longer afford to submit himself to the accident of the time and place of his birth, as almost all people in the world have done up till now.

There has been a thesis, almost a faith on the part of most of the people in the world, which is still extant and forms the basis of many attitudes. Roughly, it can be stated in such words as these: The welfare, the prosperity, the prestige, the power, and so on, of the group into which I happen to be born, or adopt at birth, is more important than the welfare, the prestige, the power, and so on, including the lives of all the rest of the people in the world - all put together! On the face of it, of course, this statement is manifestly absurd. Because the group that I happen to belong to by birth can not be more important in all these ways than everybody else in the world put together. And yet, this is the impression that children are getting all over the world - that our loyalties can be limited to the group into which we happen to be born.

In these new circumstances, in this kind of world around us now which never existed before, we can no longer afford to go on that way. We are going to have to help our own consciences to grow up to a degree of maturity that will allow us to function as members of the human race, which we have not been educated to do in the past The unit now, for the first time in the world's history, has become the human race. We will survive as a human race, or not at all! This is a situation again totally unknown to any of our ancestors and we have no learned, or early-learned, or hereditary concern for this situation. We have no conscience-values generally that concern themselves with survival of the human race. Indeed, we haven't even got a government department in any country that I know of that is set up to concern itself with the "survival of the human race." And if there is any question about which we have no government department, it obviously is not very important!

And yet, this is the overwhelming question of this generation — the survival of the human race! In order for us to learn how to cope with this, and all the problems that go with it, including, and perhaps more important than any other, the population problem, we're going to have to deal with our own conscience values. And this is an extraordinarily difficult thing to do! Because in effect it means dealing with our own prejudices, and our own limiting loyalties and demanding of ourselves that we grow up to a level of maturity that was not even considered in any previous generation. If enough people in enough places can grow up - mature - to be able to function adequately as members of the human race, then we can begin to be reasonable about population explosion, about genetics, about food supply, about nationalism, about all sorts of things with which we are not coping effectively now. And this is a personal problem for each individual. These problems can not be effectively coped with by any international agency, or any government, not until enough people in each country want their government to cope with these problems. That is a matter then of individual growth - individual recognition of responsibility. Responsibility now will have to extend itself to responsibility to the human race.

How to go about this change - how to undertake such growth is a problem for the educators of our cultures largely. Doctors, obviously, as indeed all the people working in the field of health, have an immense responsibility in this field. That responsibility is defined in the two statements that I gave from the Constitution of the World Health Organization. If and when we can assume responsibilities at that level, then all these questions of problems facing, and at the present time reasonably frightening, the human race can be tackled logically and sensibly without the emotional overtones that make it so difficult to talk about them reasonably now.

Speaker: HERMANN J. MULLER DISTINGUISHED SERVICE PROFESSOR OF ZOOLOGY, INDIANA UNIVERSITY

THE typical attitude, in our time, of the progressive liberal who has been exposed to some discussion of evolution has been a blindly optimistic one. He notes how far the line ancestral to man has come in the two to four billion years of its history. Like the gambler who has had such a fabulous streak of luck that he believes it cannot ever fail him, he ignores the multitudes who fell by the way and thinks that that cannot happen to him, even though some of them had done about as well as he, up to their point of failure. He caps his argument by pointing to the unprecedented new means of progression, cultural evolution, that man alone has been possessed of. Noting how much faster it can be than biological evolution, he is inclined to take the position that it has now superseded biological evolution entirely, and rendered it quite unnecessary.

It is true that for hundreds of thousands of years, as men's cultural evolution proceeded, it increasingly brought into being "artificial" conditions of living, and that these conditions unintentionally promoted the natural selection of biological traits and proclivities that in their turn were conducive to cultural activities and development. Thus, biological and cultural evolution were reciprocally reinforcing. At last, however, with the generation of modern science and technology, including more especially medicine, cultural evolution has entered a new phase in its relation to biological evolution. Its very successes have made facilities available that no longer afford effectively differential advantages in a competitive struggle for existence to the healthier, the abler and the more moral individuals, families, or small groups. Instead, these modern methods of overcoming natural obstacles are so nearly foolproof, knave-proof and proof against men's bodily ills as to accord to many of the genetically inadequate individuals ample powers of reproduction which they, in consequence of or in compensation for these defects, are likely to indulge unduly.

As in the parallel case of arriving at world misery through the overpopulation made possible by medical victories over death that have not been balanced by adequate medical aid in the control of birth, so here too. But whereas in the former case the promotion of the mere quantity of life results in the choking off of life's finest expressions, in this case the innermost and most precious core of life, its genetic quality, is subjected to a deterioration that is actively promoted by medical practices. Mutual aid, the uplifting of the weak by the strong, the process that constitutes the heart of civilization, is defeating its own purposes when administered so blindly as to bring about a continual increase in the need for such aid, and in the burden that it entails on the whole community. Thus what medical practices, and in fact all our powerful modern aids to living, are giving people with one hand they are in the long run taking away with the other hand. That other hand is the one that fails to extend to them the techniques and the hardwon fruits of human inquiry that would enable and induce them to exercise discrimination in their procreative decisions.

It has been known to geneticists for decades that the vast majority of mutations are detrimental, in that nearly every one of them occasions, at least to some small degree, one or more of the many thousands of possible impairments, bodily, intellectual, or in the genetic basis of the emotional organization or moral fiber, that our organism is subject to. The reason that evolution succeeded with us in spite of this prevalence of undesirable changes is that the very rare mutant who happened to be superior won for himself or his small group of relatives a chance of leaving more descendants, while the thousands of mutants less fit than the already established type tended to die out. It is not commonly realized that even the maintenance of the genetic status quo requires an active selection of this kind. For, the more that selection is diminished by aiding the reproduction of the genetically unfortunate, the more must the population accumulate from generation to generation all the constitutional ills that body and brain can fall heir to, as new mutations continue to occur and accumulate.

Although this process is, even at its worst, a far slower one than the present rate of aggravation of human overcrowding, nevertheless its substantial magnitude can be gauged from a surprising conclusion arrived at by modern genetics. This is the fact that at least one in every five persons, on the average, is encumbered with a mutant gene that arose "spontaneously," as we say, in a reproductive cell of one of his parents. He received this, of course, in addition to the many other mutant genes that had arisen in earlier generations and had been regularly transmitted to him by his parents. Moreover, in arriving at this tally of at least one in five persons having a new mutant gene, we are leaving out of the reckoning any newly arisen mutations that may have been induced by one of the many novel practices of our day, such as exposure to radiation and to possibly mutagenic drugs, cosmetics, contraceptives, food additives, industrial wastes that are thrown out into the air or water. None of these suspect chemicals has been adequately tested in this regard, that is, as to whether it is mutagenic. It is obvious that unless people of the genetically least fortunate fifth of the population, when saved for reproduction by the triumphs of modern medicine and other technologies, reach a firm decision not to pass along their burden to posterity, the genetic quality of future generations must inevitably undergo decline.

We see, then, that since our new techniques of healing and of prophylaxis are breaching the natural dam of selection that holds up the genetic quality of our species, these techniques must now be balanced by new attitudes regarding the goals to be aimed at, and also balanced by other techniques that can materially implement our progress toward these goals. Both the general public and the members of the medical profession must be given, from childhood on, a more meaningful education in the fundamentals of genetics and evolution, one that they will carry into their judgments and decisions regarding their work and their own living, and into their sense of values and moral feelings. When they have been awakened to our increasing human load of mutations and of all that this implies, they must come to recognize their own obligation to aid in the production of a future generation not worse, genetically, than their own, but, if possible, better. They must rise above the antiquated view that reproduction is chiefly the means whereby parents may indulge their selfish vanity in the idiosyncracies that chance to characterize their own stirps, or the stirps of the clan or so-called race they happen to belong to. They must replace this anachronistic attitude with the more ethical, civilized view that reproduction is chiefly the means of bringing into existence a family, and a generation, of more truly human beings; that is, beings who have been endowed as far as possible with those genetic virtues of health, stamina, ability, loving-kindness, that the elders in their deepest hearts wish that they themselves could have had in greater measure. This is, after all, but the Golden Rule, applied in the realm of human genetics. If, as some critics claim and others deny, this means a kind of abnegation, it is abnegation of that type which rises above self, into the glory of acts of achievement and creation that bring the deepest sense of fruition.

The early communists' dreams of plenty of material goods, reasonable hours of labor, and a worthy education for everyone are more than half way toward realization in our own moderately free society today, because our techniques of production have advanced so much as to make all this possible. Similarly, the dreams of Galton and the early eugenists, of a voluntary reproductive selection whereby the genetically less fortunate would contribute fewer progeny and the more fortunate a larger number, are now at last becoming possible of attainment, because of modern advances in the techniques of reproduction. For example, the fear that atomic war or the illmanaged disposal of waste from atomic reactors will contaminate the hereditary material entrusted to us for future generations is in part an unnecessary fear, if only we will avail ourselves of at present available techniques by maintaining, underground, banks of deep-frozen spermatozoa from every man. This would be a procedure far less costly than that of establishing bomb shelters for all. In these banks the germ cells of men, at any rate, would be kept far freer from all mutagenic influences than are the germ cells within the body. Perhaps a relatively small amount of research would make a similar procedure possible for women.

At the same time, the storage banks would make these germ cells available for indefinitely long periods of time, so that they could be utilized even after the decease of the individuals themselves, thereby, in a sense, evading their bodily deaths, supposing for instance that they were killed in war. Surely, under these circumstances, many couples, desiring to make a significant contribution to the good life, would decide to take advantage of such an opportunity for genetic choice by having, right in their own family, a child who had derived his genes from the source they held in deepest regard, rather than a child whose genes had been determined purely by the chance of what their own genetic composition was. And they would tend to bring up this child of choice rather than chance as their very own, with all their warmth, their tenderness and their justly founded pride.

Important new techniques are likely to break through into general use byway of many different channels, in consequence of the diverse benefits they offer. Breaking through in various ways, of which that just sketched is only one example, the new techniques of reproduction must eventually come to afford the necessary balance to our present genetic predicament. Reversing the present downward genetic trend, they offer the hope of not merely compensating for ailments and weaknesses, but of allowing a resumption, under conscious guidance this time, of our progression toward an ever higher estate. Thus we should be able to give free rein to our advancing medicine, while at the same time actively helping future generations. And we should thereby have advanced from barbarism to civilized practices in that major field of human life that has till now remained in its essentials the most untouched by culture, namely, the field of reproduction.

Dr. McDermott: I find myself at quite large dissent from much of what has been said. I refer first to the problems of population control. And, in order to get the record absolutely straight, may I make the point that I am not a member of any organized church. Nevertheless, it seems to me that the argument put forth, which is the conventional argument, is unconvincing, and having devoted considerable thought to this, as we all have - and I happen to be especially engaged in research in technological development - I find myself, perhaps rather reluctantly, coming to the conclusion that population control on a programmatic basis, at least, is simply unconvincing.

What are the reasons for this stand? The strongest argument has to do with the food supply, but it seems to me that all the rest of the arguments have to do with our viewing with Western eyes a situation that is not Western at all. Several times this afternoon the statement has been made that our birth rate is going up because of the application of modern medicine throughout the world. Now, no one has yet mentioned the Island of Ceylon, but whenever you scratch a demographer, he always comes up with Ceylon, because the two things have occurred together: modern medicine has been applied and the birth rate is going up. But birth rates are going up in many other parts of the world and I think all of us who are familiar with the problems in the economically underdeveloped area, know that despite the valiant efforts of W.H.O. and UNICEF and other wonderful groups, it's illusion to believe that the benefits of modern medicine are being applied on any world-wide scale at the present time....

I have had some experience in doing an absolute birth-rate count. By "absolute" I mean no samples - to go out there and count the babies in an underdeveloped situation. And when one does that, I think, as all demographers would agree, the birth rate is indeed higher than the anticipation rather than lower. So that the birth rate is going up - it fluctuates - it does go up high in various parts of the world, but the case that this is occurring because of the application of modern medicine ... I believe that I challenge.

The second point has to do with the idea that if the population gets so large all our gains in the standard of living will have been lost. If this affects the food supply — in other words, if the population actually does outrun the food supply, which by pencil and paper one can show quite easily, but in history has not yet been demonstrated - then I will become convinced. But as for the other aspects of the standards of living - these are in Western eyes! In the middle of an Indian village there are no television sets to buy; there are no colleges with tuition, yet - I mean, they will come. There are none of the things that we call "a standard of living." It makes no difference if there are eight or there are two, so that except for the food supply I think that neither of these cases - that modern medicine has been applied on the one hand, or that the standard of living will be reduced on the other hand - is there.

Aldons Huxley: Whether, as Prof. Muller suggests, we can as a matter of practical policy impose or get people to accept a system of eugenics seems doubtful. I think the best we can hope for at present is possibly to encourage certain forms of negative fear of eugenics - that is to say, of discouraging people with obvious genetic defects from reproducing their kind; and for the rest it seems to me we have to find out what are the best environmental conditions for eliciting the enormous potentialities of human beings. I think it's quite clear that most of us are functioning in the terms of engineering at about 15 per cent of capacity. And it would be very nice if we could function, say, at about 20 per cent of capacity. I think there's very good reason to suppose that if we set to work, not merely to develop the conceptual part of the mind, but actually to educate the mind-body which has to do the learning and the living, to educate the perceptions, to educate the whole muscular system, to educate the imagination then, I really do think that even given the present not extremely high level of genetic accomplishment, we could get a great deal more out of ourselves than we are getting now. It is possible, of course, that in the future positive eugenic policies may come into play. I don't know, but I think this is extremely remote. And, of course, we are at present pretty much in the dark as to what exactly we are selecting.

If I may quote my own excursions into this field, in the prophecy of the future which I wrote nearly thirty years ago - I placed it five or six hundred years ahead, but unfortunately a great many of its forecasts are already coming true in that prophecy I made it clear that there would be a simultaneous attack on the human problem, both from the genetic and the environmental side, and there it was a totalitarian regime which artificially produced certain types of human beings which were useful for specific social purposes. And this, I think, is by no means out of the question. I think it is possible that this could be done. I don't think there's any likelihood of it's being done in the near future, but unfortunately I think it is quite clear that the whole idea of human breeding does lend itself very much to some kind of totalitarian manipulation. And for the present, perhaps for this reason, I feel we should concentrate more, first of all, on avoiding the more obvious genetic defects, preventing the more or less genetic defects from being multiplied, and in the second place, on seeing what can be done with the capacity that we already have.

Sir Charles Snow: A number of the speeches have borne on topics which we raised this morning on problems like statistical morality, the extended imagination and what I think, from Mr. Brock Chisholm's extremely moving speech, I should now like to call the "extended conscience" - that is the conscience that contains in it an element of foresight. And foresight seems to me, the more I think of these things, perhaps the most essential quality that sensible men have got to train themselves into.... And with this extended conscience, it seems to me, one has got to think about problems such as the future size of the population. I think that beyond a reasonable doubt there is a limit beyond which the race can't reasonably, or tolerably, exist. I thought Doctor McDermott with great charm and blarney slightly got away from facts which I think are there only too plain for us all to see. I agree that at the moment the gloomier prophecies are not coming through. That is, at present so far as we can see the available food supply is keeping up a little more than the population is going up. That is true. It is also true that there are many people by temperament - and I think that with those I would include myself - who are not so indisposed to see an increase in population. That is, there are some people who like crowds, and some people who don't like crowds. And so, by temperament, I have nothing against a world which is appreciably larger than it is now. At any rate, I don't hate great urban aggregations, as Mr. Huxley does.... There is something to be said for an increase in population. Don't let us take it too tragically, if we can keep it within terms which the race can materially survive. But there is a limit, I have no doubt, and I'm afraid that that limit is very nearly upon us.

But I would say this, because among Dr. McDermott's charming blarney there is also humanity: It is very important that we do this with the best psychological manners at our command. It mustn't come from the West, sitting fairly pretty, having substantially controlled this problem ourselves, having quite enough room at our disposal, far more than enough. It is not for us to say to the East, "This is about the size you ought to be." ... The West must be very careful what it says. Any real move for the control of numbers of the human race must, I am sure, come from countries where the explosion is now about to begin, or has just begun. On that I am quite clear, and I think we must constantly remember it....

I would like to say a rather similar word about eugenics. I think it is not for us in our generation to try and tell future men everything they should be like. I don't think we're omniscient. I think we've got to show a proper humility. They may choose to be very different from what we would like them to be. And, therefore, I find myself very strongly on Mr. Huxley's side. I think we've got to make the environment tolerable. "Leave if you like" is a strange legacy to our descendants. Dr. Muller's great pool of sperm - that seems to be one of the really original bequests one generation might ever leave to another. But leave it there for them to make the choice. They are going to live in a very different world. They're going to live in a world, as Dr. Chisholm began by saying, which will be in many ways unimaginably different from anything that we have lived through. They have got to make that other world. Let us leave that for them. We can't take too much upon ourselves. If we leave them a world which is tolerable, which is not faced by great biological disaster, then I think they will probably feel that we have done our best.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIt Was A Dartmouth Jinx All the Time

November 1960 By AMOS N. BLANDIN '18 -

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Year in France

November 1960 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Feature

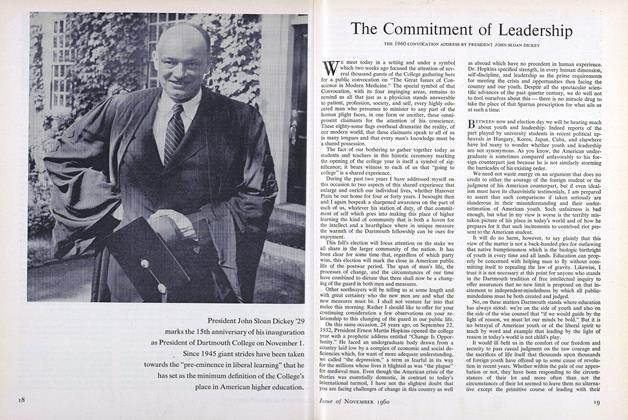

FeatureThe Commitment of Leadership

November 1960 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

Feature"The Era of the Shrug"

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleEvening Assembly

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleFirst Panel Discussion

November 1960

Article

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Publications

June 1939 -

Article

ArticleFourth Hanover Holiday Program Announced

March 1940 -

Article

ArticleEstate Planning Group Has Regional Meetings

January 1957 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

OCTOBER 1972 -

Article

ArticleIn the Tower Room

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

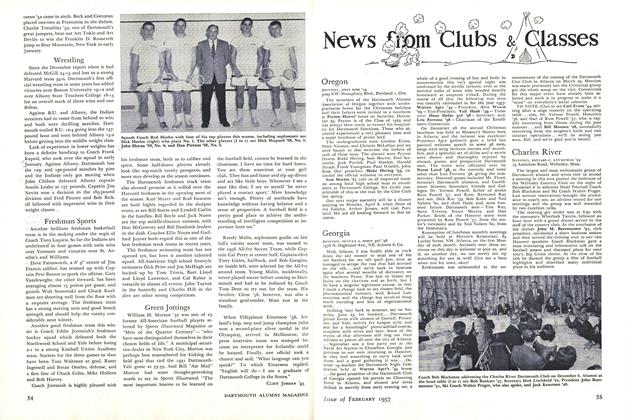

ArticleWrestling

February 1951 By CLIFF JORDAN '45