PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY

THIS is an account of a Fulbright year in France. During the academic year 1959-60 I was a visiting lecturer under the Fulbright program at the University of Rennes in Brittany for the first semester and at the University of Aix-en-Provence for the second. The basic purpose of Public Law 584, 79th Congress (otherwise known as the Fulbright Act) is to "increase good will and understanding between the people of the United States and the people of other countries through the exchange of students, teachers, university lecturers and research scholars." I cannot, of course, vouch for the amount of good will and/ or understanding between the people of France and the people of the United States that accrued from my Fulbright year. But I can speak for this particular university lecturer. This was one of the most rewarding experiences of my life.

It was both a new intellectual and a new social experience. As a sociologist, I am interested in both types of experience, and I shall try to organize my impressions about this theme. I shall speak, briefly, of interpersonal (social) relationships in several related contexts: notably, (a) between faculty and students, (b) between faculty and faculty, (c) between faculty and "administration," and (d) between students and students. In each of these respects, the relationships are very different from those in an American college.

FACULTY AND STUDENTS

When I entered my first class, all the students rose and remained standing until I sat down. Then they sat down, opened their notebooks, took out their pens, and looked at me expectantly. It was up to me to communicate. This is, after all, the basic requisite of the educational process. And this was, of course, the most difficult part of all for me. I am not a professor of French (as the latter say, French is not my metier), and the students understood little or no English, even though most of them could read it. Hence even my bad French was more comprehensible to them than reasonably correct English. I have spent a good deal of time in France in recent years (I trust the reader will forgive the personal pronoun), and hence have had considerable first-hand contact with the spoken and written language. But it is one thing to read a newspaper, order a meal, and converse in a fairly intelligible fashion with one or more people. It is quite another thing to deliver a lecture in a language not your own. In any event, I was on my feet and on my own.

In my opening lecture, I tried to tell the students something about the system of higher education in the United States, the number of colleges and universities, the different levels of admission and of instruction once you are admitted, the methods of teaching, and the reasons people go to college. In France, incidentally, there is a sharp distinction between the "college" and the "university." The former term refers almost exclusively to the lycee or "college," which is the core of the system of secondary education. It is confusing to them to speak, as we do, of college and university education as (on the undergraduate level at least) referring to the same thing. When I told them I was from Dartmouth Col-lege, they naturally assumed that this was a lycee and that enterprising students then went on to, say, Harvard for their higher education. I did my best to disabuse them of this notion.

A word is in order about the composition of the student body in a French university. First and foremost is the generally high intellectual standard. University students in France and, for that matter, in all the continental countries, constitute an intellectual elite. To be admitted to the university, they must pass the Baccalauréat examination at the end of their training in the lycée. The same examination is given at the same time all over France; approximately half of the students who present themselves (and many do not even try) fail the first time, and only a fraction more pass the second time. The Bachot is front-page news in France and the questions are published in all the Paris newspapers. The system has in recent years been criticized as being too difficult and thereby depriving the nation of thousands of people who, because they did not remember the date of, say, Charlemagne's death, never get to the university. The system remains, however, essentially what it has been for generations - namely, an extremely difficult intellectual hurdle.

The students are, therefore, a highly selected and motivated minority of their total age group. They come to the university, usually, to prepare for a specific career in one of the liberal professions. They receive most of their "general" education in the lycee, where they specialize in what we would call the "humanities" - that is, ancient languages, French, modern languages, history, philosophy (perhaps the heart of the entire program), and mathematics. The majority thus reach the university with their "liberal arts" training virtually completed; they then enroll directly in one of the several Faculties - Letters, Law, Medicine, Science, or Pharmacy. The work in Sociology is still given in the Section (Department) of Philosophy, which also includes Psychology in all its varieties. The awarding of formal credit through the Certificat in Sociology is a very recent development, even though France produced one of the great modern figures (Durkheim) and a Frenchman (Comte) gave Sociology its name.

In my early lectures, the students listened politely, wrote down everything I said (presumably translating my remarks into acceptable French), and did not, until much later in the semester, dream of asking questions or "discussing" anything brought up in the lectures. After the initial shyness wore off, they did begin to question me and express their own opinions. In this latter respect, they are very different from American students, who have been encouraged by the "discussion" technique to give you the benefit of their wisdom on a great variety of matters, whether they know anything about them or not. Many American professors maintain that such discussion is an end in itself, no matter how uninformed. This educational philosophy may be open to question; in any event, my point is that it has not yet reached France.

The relationships between faculty and students, as I found them, were pleasant but not intimate. At Christmas time, I received formal little notes from a number of my students at Rennes. Others gave me the season's greetings in person. As the time went on, the language barrier became less pronounced, not only because I became more fluent but also because the students gradually began to realize that they could understand what I was saying. Few professors, if any, call students by their first names. The opposite is, of course, virtually unthinkable. This situation, in final analysis, reflects a different culture from the free-and-easy democracy of the United States. The French student, like his elders, is polite but not effusive.

FACULTY AND FACULTY

The second type of interpersonal relationships involves one's colleagues. In the first place, the number of professors is comparatively small in France, at least as compared with the United States. The entire Faculty of Letters at Aix, for example, has only about thirty full professors and perhaps an equal number of instructors in other ranks. The student body numbers well over four thousand in Letters alone. In the whole of France in 1959 there were only 279 full professors in all the Faculties of Letters, plus other categories to bring the total up to less than a thousand instructors all told. There were approximately 55,000 students in Letters for the entire country, of which almost half were in Paris.

The comparatively small number of university teachers reflects at least two related conditions: (a) the continuance of the lecture system in most fields, whereby one professor is heard by a large number of students; (b) the system of advanced degrees and promotions, both of which are extremely slow. (One of my colleagues described this as a "mandarin" system, based as it is upon wide learning and leisurely advancement.) The professor must take a doctor's degree (the Doctorated'etat) which is viewed as virtually a life work. Most people do not receive the doctorate until they are well into their forties, and they usually do not get their full professorship until they have completed the degree.

Shortly after my appearance at both Rennes and Aix, I was invited to a group dinner at one of the local restaurants for the members of the Section of Philosophy and their wives. This being France, a great deal of careful attention was paid in advance to the ordering of food and wines. The Doyen (Dean) of the Faculty of Letters was present and, after the dinner and the wines, the head of the Section (i.e., the senior professor), the Dean, and your own correspondent were each called upon for a few well-chosen words. My own were, I need hardly add, both fewer and not so well chosen as those of my colleagues. However, I did my best for the honor of Dartmouth College, the Fulbright Act, and the United States of America.

Another pleasant faculty custom is to schedule public lectures for six in the evening. After attending the lecture, usually given by a visiting professor, the members of the Section go to dinner, again at a restaurant, and thus honor the speaker. At the same time, the wives do not have to get dinner, one regales oneself at a modest price on the French cuisine, and all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds. In the month of May, I was the visiting lecturer at a public lecture. When that was over, I was ready for a nourishing glass of the wine of the country.

Speaking of conviviality, I had the honor of attending a hands-across-the-border ceremony at Aix, given in honor of several visiting professors from the University of Tubingen. The gathering was held in the handsome reception hall of the Faculty of Letters, decorated with frescoes and opening on a court. Down the middle of the hall ran a long table, on which a row of champagne glasses was neatly arranged. At a signal from the Doyen, we all advanced to the table, took a glass of champagne, and toasted our guests. The Doyen gave a graceful little speech in which he remarked (in passing) that he knew parts of Germany rather well, having spent four years there as a prisoner of war. The toast was answered by one of the Germans mans who, it turned out, had spent his student years at the Sorbonne and at Aix in the decade before the late unpleasantness. He pointed out that Tubingen felt somewhat humble before Aix in point of view of age, the former dating only from 1468 and the latter from 1409. After that, we drank another toast to both universities and to the ancient and honorable status of higher learning.

FACULTY AND"ADMINISTRATION"

I use quotation marks in this context advisedly, for the "administration" has a very different meaning in a French (or other continental) university than in the United States. Each university district in France is under the nominal direction of a Recteur, appointed by the Minister of Education and responsible for all primary and secondary, as well as higher education. The Recteur is the closest thing to an "administrator" they have, but he does not have much to do with the actual running of the university. For all practical purposes, the various faculties are autonomous bodies, each electing its own Doyen and making its own policies. This officer is elected by the full professors from among their number, and his role is that of first among equals.

The educational policies are made in the Assemblée, a body composed of the full professors and some of the other instructional groups. As a visiting professor in good standing, I was invited to attend these sessions, and I was delighted to do so. The Assemblée decides on everything from the time of final examinations to the appropriations for the library. In between, this august body touched on a variety of other matters, including: (a) the awarding of student prizes (one such prize at Aix being called, happily, the Cezanne Prize in honor of the great painter whose home town this was and who, for a time and most reluctantly, attended the Faculty of Law); (b) changes in the curriculum (several of the professors remarked, for the record, that they were thinking of giving several new courses next year, which was all right with everybody); and (c) promotions and awards to members of the Faculty (including several colleagues recently awarded the Legiond'Honneur). The younger members of the faculty have an indirect voice in these and other matters, largely through the senior professors in their sections. In general, however, the junior members wait until they are full professors.

In addition to the Doyen, each Faculty has an organization known as the Secretariat, which occupies itself with all the housekeeping chores. The members of the Secretariat are appointed by the state, wear long grey smocks, and are very respectful of the professors. The students pay their fees to, arrange for their examinations with, and receive notices from the Secre-tariat. The professors get their mail from, have their mimeographing done by, and place their telephone calls through this same organization. The Secretariat, in short, serves as a sort of combined Bursar's Office, Registrar's Office, and Department of Buildings and Grounds.

In one of the meetings of the Assemble, a recent student strike came up for extended discussion - not so much in terms of the strike itself, with which both the Dean and the Professors were in hearty accord, but because of an unfortunate episode involving the police. A "strike" in a French university consists of staying away from lectures by the students, having a mass meeting, and generally indicating their unhappiness with the way things are going. There were two student strikes during my year in France, one involving the amount and allocation of scholarships and the other a recent governmental decree concerning the postponements (not exemptions) of certain categories of students from military service.

In the course of the demonstration at Aix, however, several members of the local police force took it upon themselves to invade the university buildings without being specifically asked by the Doyen. When the latter heard of this unwarranted invasion, he immediately protested vigorously to the Prefect of Police. This unhappy officer apologized humbly, said it was all a mistake, and promised that it would not happen again. The autonomy of the university on such matters is an ancient prerogative that goes back to the founding of the University of Paris in the thirteenth century. Since then, it has been extended to all French universities. The rights of Gown against Town are jealously guarded, both in custom and in formal law, and the university authorities intend to keep it that way. When the Dean told the assembled professors of the steps he had taken, he received hearty and unanimous approval. This principle is taken seriously.

STUDENTS AND STUDENTS

I approach this fourth type of interpersonal relationship with some hesitation, inasmuch as I was not involved directly. Nevertheless, some very general remarks may be interesting, for the contrasts between the French university and the American college are perhaps more striking here than in any other respect. Student life is obviously an important aspect of the French university, but the latter is not the tight and self-contained little world of the American campus, especially at such institutions as Dartmouth. Only a handful of students live "on campus" - that is, in the Cite Universitaire built by the university and providing lodging for a few students and meals for a good many more. Most students live in rooms in the city and eat wherever they can afford to. Their time at the Faculty is largely spent attending lectures and studying in the library. The Big Man on Campus is unknown in such an environment.

Furthermore, as noted, students come to the university primarily for intellectual reasons - not to enjoy a pleasant respite between high school and work, because it is the thing to do, or to make contacts that will be valuable in business. Their academic standing will either haunt or help them the rest of their lives, and their intellectual motivation is correspondingly high. The reading rooms of the library are full from morning to night with boys and girls who are studying - not whispering, talking out loud, reading the comics, or sleeping with their shoes off.

French universities are coeducational, but primarily for educational and intellectual, rather than social or matrimonial, reasons. Girls come to the university to prepare for various professions (teaching, child welfare, social service, medicine, the law), and not primarily to get married. I do not mean that the atmosphere of the long marble halls is exactly monastic, but I do mean that coeducational contacts in France appear to be incidental to other ends, rather than ends in themselves. The girls make little effort to "dress up." Most French coeds come from homes of modest circumstances and they wear what clothes they have.

Campus activities are run on a very informal basis. Athletics are really amateur in the French university. At the beginning of the fall semester at Rennes, a flurry of handwritten notices appeared on the student bulletin boards, suggesting that, if one were interested in playing football (soccer), he might drop around some afternoon to the office of the football club. Then they would all see if they could put together a team this year.

Much of the "social" life of the students, apart from that in the cafes of the town, is centered in intellectual clubs, formed by the students themselves and sometimes having the use of a vacant room lent by the university. At Rennes, the Social Psychology Club was the place where the Sociology students gathered. They had fixed up the room themselves, painted murals on the walls, chipped in to buy a coffee machine and a record-player, and they were in business. The records ranged from Beethoven to Basie, but not Elvis Presley. French students are very interested in American jazz, which they take seriously as an exotic cultural manifestation, and which they ap- proach in a highly intellectual fashion. The members of the Social Psychology Club were fascinated when I told them that, in my own misspent youth, I had actually listened to the great Louis Armstrong on La Rue Trente-Cinq (South 35th Street) in Chicago - a good twenty years before they were born.

In these brief pages, I have tried to indicate some of the differences between the French university and the American college in terms of several types of interpersonal relationships. In each of these types, the differences are considerable; in some, they are striking. Like any other institution, the university reflects its social setting. The French student is exposed to a different set of cultural expectations than is the American student. There is, of course, an emphasis upon the things of the mind in any institution of higher learning. But in addition to this intellectual foundation, the American student is interested in empirical training, in practical results, and in social contacts. One educational system is not necessarily "better" than the other. They merely perform functions in very different societies.

I shall end this account, as I began it, on a very personal note. The Fulbright year was, above all, a highly personal experience. After a quarter of a century at Dartmouth, the year in France evoked many personal adjustments, not the least of which was living and lecturing in a language not my own. I made a number of lasting friendships among my colleagues at Rennes and Aix, and I hope to see them in the years to come, whether in Brittany, Provence, or Hanover. I lived through an exciting and crucial year for France, and I experienced many of their uncertainties through the eyes of the people themselves. For all these, and many more, experiences, I am deeply grateful. I should like, therefore, to express my deepest appreciation for this unique privilege to Public Law 584 and to the senior Senator from Arkansas.

"La Cité Universitaire" provides lodging and meals for university students at Aix

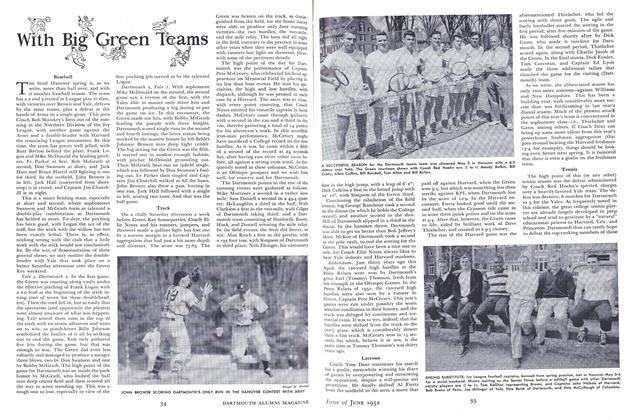

This 15th century chateau at Lourmarin, near Aix, is owned by the university and serves as a center where students in the creative arts study and work during the summer months.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIt Was A Dartmouth Jinx All the Time

November 1960 By AMOS N. BLANDIN '18 -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Leadership

November 1960 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

Feature"The Era of the Shrug"

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleEvening Assembly

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleSecond Panel Discussion

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleFirst Panel Discussion

November 1960

FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26

-

Sports

SportsYALE 6, DARTMOUTH 0

December 1945 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsMISCELLANY

January 1947 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsTENNIS

June 1950 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsFootball Broadcasts

November 1950 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Sports

SportsTRACK

March 1951 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Sports

SportsLacrosse

June 1952 By Francis E. Merrill '26

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Dinner Honors Football Team

FEBRUARY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureDE Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

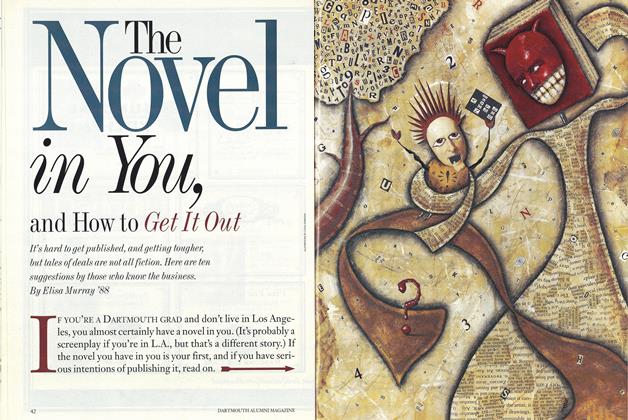

FeatureThe Novel in You, and How to Get It Out

DECEMBER 1996 By Elisa Murray '88 -

Feature

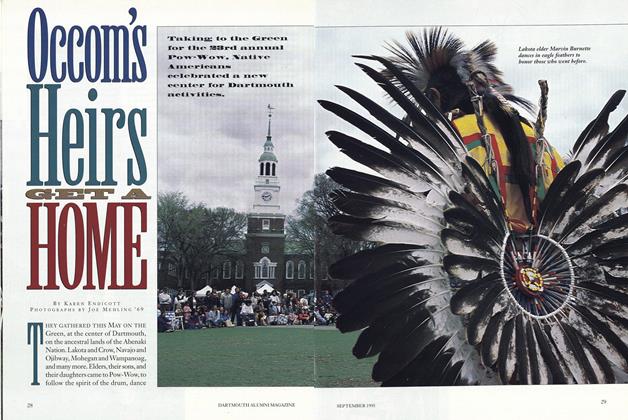

FeatureOccom's Heirs Get a Home

September 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1964

JULY 1964 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureThe Second Emancipation

JULY 1963 By THE REV. JAMES H. ROBINSON, D.D. '63