Speaker: MAHOMEDALI CURRIM CHAGLA INDIAN AMBASSADOR TO THE UNITED STATES AND MEXICO

IT is an honor and a privilege to address this Convocation on the Great Issues of Conscience in Modern Medicine. The honor and privilege become even greater when I am sharing it with so distinguished a writer and humanist as Mr. Aldous Huxley. I have always been a great admirer of Aldous Huxley's writings. I remember reading his earlier book of poems Leda and I have always regretted that he deserted the muse of poetry. His novels provided a thrill and excitement to English literature that it then lacked. And for many years now Mr. Huxley has preached the message of humanism and held before a rather skeptical world the values which it is fast forgetting or ignoring. It was indeed an essay of Mr. Huxley's which vividly brought home to me the problem that the world is facing in the population explosion which is taking place before our eyes and which, with that delightful knack of refusing to notice unpleasant facts, we pretend is not explosion at all but just a natural phenomenon which God in his goodness has ordained and which we sinful mortals must accept with proper Christian resignation.

Let us first look at a few figures. The population of the world in the 17th Century was 500 millions. It is about three billions at present. Every ten seconds 31 new babies are born into the world. In my own country, which is about one-third the size of this country, the population is more than 400 millions and is rising every year by about eight millions. In China, which is the problem country of this decade, the population is 600 millions and the Government of that country welcomes a continuous increase in the population as providing it with a greater potential for expansion and, may I say so, aggression.

The great crisis of this decade is not one of differing ideologies. The great enemy and the threatening menace that we have to face is not communism. The really explosive factor is poverty. The per capita income of 1¼ billion people in one hundred less developed countries is less than $100 a year as compared to the per capita income in the U.S. of $2,100. In my own country it is a little more than $60. And by a curious twist in the working of natural laws, the largest increase in population is taking place in these underdeveloped and poor countries. What does that mean? It means that population explosion is increasing every day and every minute; the number of people living below the minimum standards of subsistence, the number of people who are uneducated, who are unemployed, who are frustrated and who have no hope of a better future for themselves or for their children, is also increasing.

It is poverty and distress that is the most potent source of communism. The last twenty years have seen many countries in Asia and Africa achieving freedom. They have thrown off the colonial yoke, but are still left with a colonial economy. Freedom after all is only a means to an end. It acquires significance only if it can satisfy the inner craving of man. Is it surprising if these newly freed people of the world should compare their own standards of life with those in this country or in the affluent countries of the West? The aspiration for a better life is a laudable one but the great question mark of today and tomorrow is whether that aspiration can be satisfied in a free society. The answer given to that question by Russia and China is that the only way to fight poverty and bring about industrial and economic development is to regiment people and to prefer material progress to the welfare of the spirit and the soul. We in India are attempting to give a different answer. In our last thirteen years of freedom, we have maintained democratic institutions and have granted full freedom to the individual in thought, expression and even to a large extent in action, and at the same time we have launched upon the gigantic task to raise the standard of our 400 millions. But we must fight poverty successfully within a measurable period of time. Otherwise we will have demonstrated to other independent countries in Africa and Asia that democracy and free institutions are no answer to underdeveloped countries: they are an exotic plant that can only flourish in an affluent society. People will turn to totalitarian methods if they are driven by poverty and if they can find no relief by adhering to free and democratic institutions. The continuous increase of population in underdeveloped countries constitutes a growing threat to freedom and democracy.

We in our country are about to complete our second Five Year Plan and in the last ten years we have made considerable progress in transforming the economy of our country and in raising the standard of our people. We are particularly concerned about our food production. Our country is a country of villages and farmers and up to now, to a large extent, our economy has been an agricultural economy. The farmers press heavily upon the land. They need fertilizers and the land is so parcelled out that the only solution is a system of cooperatives. We are industrializing our country in order to take people off the land and we are setting up fertilizer factories and large irrigation dams. We have increased our food production considerably, but whatever we do we have all the time, as we march forward, to look behind us at the specter of increasing population. The population is always catching up with our progress.

This country has given us a great deal of economic aid. She has given us a great deal of food supply out of her abundant grain surpluses. It is clear therefore that there is a full and clear realization in this country of the important role that India is playing in Asia and how important it is that her economic experiment should succeed. The new nations in Asia and Africa are watching India to see whether democracy can solve the problem of poverty. It seems to me that this country should not only be interested in giving economic aid to India but also equally interested in the fight that India is putting up, with which I shall deal later, to control her rising population.

At one time a rising population did not present a serious problem to India. There were always epidemics, or local wars or a heavy infant mortality and a low expectancy of life to counterbalance the large number of births. I may also point out that people in those days looked upon a large number of children as an insurance - so few survived that a large family seemed to be essential. But all that has changed now. Advance in medical knowledge, steps taken to improve standards of hygiene have eliminated many diseases in India which took a heavy toll in lives. There are no epidemics now and if one breaks out it can be immediately put down. Civilization no longer believes in small local wars - we have to wait for a nuclear holocaust. The result has been a sharp fall in the death rate. But the birth rate has remained the same. So in a sense we have been suffering from the civilizing effects of science and medical research. Civilization has shown us how to reduce our death rate but so far has failed to point the way to a controlled population. I think this is one of the most important issues of conscience in modern medicine. Medicine must advance on both the fronts. If it considers life is sacred and everything must be done to prolong it, it must also prevent human beings being born into an existence of poverty, destitution and frustration. The sanctity of life demands that the dignity of the individual must be upheld. What dignity will millions of children have who are being born today?

This country has fought a ceaseless war against disease in different parts of the world. There are national institutes of health and other organizations which are carrying on unceasing research in cancer, malaria, typhoid and other fell diseases which the human flesh is heir to. But Government and official institutions fight shy of doing research in the problem of human fertility. Why? To my mind increasing population is a more terrible sickness from which a country can suffer than the diseases with which medical science is presently concerned. Cancer or malaria can only kill the body. When you have unwanted children, when you have children whom you cannot feed or clothe or educate, you maim the soul - you leave a scar which destroys the equanimity of mind and twists and distorts the human personality.

I have heard it being said that this country should remain neutral on the question of birth control or family planning in a foreign country. I have no desire to interfere with the domestic policy of this country. Indeed, it would be wrong, looking to the position I am occupying here, to criticize or comment on any matter which is primarily the concern of this country. But this is something which concerns the whole world. This country is not neutral when it is a question of fighting disease in other parts of the world. It has poured out millions and billions of dollars in order to improve the standards of health everywhere. There are few countries which have shown such missionary zeal in the cause of human advancement. I am sure that if it is once realized that the increase in population is a grave menace facing the world, then this country will also realize that this menace must be fought on a global basis and all the resources of the civilized world should be utilized to fight this menace.

I should like to say a word about the ethical or moral aspects of the problem. To my mind morality consists in giving the least pain to fellow human beings and contributing to the largest extent to their well-being. This is not, I fully appreciate, a philosophic definition of morality. But it is a pragmatic one and can serve as good a guide to human conduct as any other. Applying this test, I think you are causing more misery and suffering to untold millions by denying a knowledge of birth control technique than by doing everything possible to bring home to the people in this country the vital urgency of the problem of population explosion that is facing the world. Nor am I impressed by the argument that it is morally wrong to take life - that we should trust to a benign and benevolent Providence to feed all the mouths that exist in this world. Experience, unfortunately, does not prove that all mouths are in fact fed. Millions in Asia and Africa go hungry and underfed. I would rather prevent life than bring into existence children who do not and cannot live as human beings and who are a shame and a scandal both to Providence and to man.

We have been so engrossed in recent times with the dangers of nuclear bombardment that we have ignored the more insidious but equally dangerous consequences of an uncontrolled population. If millions who are being bom today are going to suffer privations and disease and may grow up into abnormal and twisted personalities, it is not a situation which can be faced with greater equanimity than the large destruction that might be caused if a war were to break out. At least, if we are all dead, we will have no problems. But if we continue to live or if we are allowed to live, then we will have a problem which, if attention is not paid to it immediately, might soon become insoluble.

You might well ask me what India herself has done toward the solution of this tremendous problem that faces her. We are one of the very few Governments in the world who have officially adopted a policy of birth control and family planning. It is not easy for any Government to do this. There are orthodox people in every religion who are opposed in principle, whatever the principle may be, to birth control. Religions in India are no exception to this. But our Government has placed the welfare of its people before religious sentiments, and even at the risk of offending these, has set up clinics in various parts of India to propagate extensive knowledge about birth control and distribute contraceptives free of any cost. We have about 1800 such clinics now and by the end of our next five year plan - in five years time - we hope to have about 8200. I agree that this is merely the fringe of the problem. But with our limited resources it is not possible to do more at present. One very satisfactory feature of the situation is that people, by and large, are cooperating with Government in this scheme. The poor people are beginning to realize what a burden and a curse a large family can be. They are even going in for sterilization. Government has authorized every hospital to perform this simple and painless operation but on condition that a person wishing to undergo it must have at least three children. This, you will agree, is much too drastic and irrevocable a remedy. But the very fact that people are resorting to it in large numbers shows the gravity of the situation.

To my mind, the real solution of this problem in India is a cheap oral contraceptive - a contraceptive as cheap and as easily available as aspirin or quinine. We can flood the market with such a contraceptive - and in twenty or thirty years we will have a social and economic revolution in India which will change the face of the country. The mechanical contraceptives we now have are expensive and uneducated people cannot be easily induced to use them.

What can this country do to help us? I want to make it clear that we do not want any money for this purpose. All that we want is science and technical knowledge being fully utilized in this country to discover the oral contraceptive I have referred to. Many private institutions here are working at it - but that is not enough. We have here magnificent national institutions of health which are working full time on research into many diseases and maladies - not only those which are prevalent here, but in any part of the world. Why ignore one of the most serious afflictions from which the world is suffering? I know that it is very often not considered respectable here to talk of birth control or family planning. It used to be the same about venereal diseases. Thousands of patients used to die because they dared not disclose the nature of their ailment. But that is a matter of the past. Medical science and medical conscience have advanced since then. A further great advance is necessary. It is for modern medicine to realize that this is one of the great issues of conscience today. And it is for scientists and doctors to preach the gospel of more knowledge and more research in this rather neglected department.

I am not unaware of the fact that there is one other remedy for increasing population and that is raising the standard of living. If we in India can overnight by magic raise our per capita income from $6O a year to anything approaching $2000 of your country, the population will be automatically controlled. In the last ten years we have been able to increase our per capita income by 20% - and if we succeed in doubling this effort in the next ten years, the results would still be pitiful. We have to fight poverty in India on both fronts on the economic front by industrialization and on the population front by devising ways and means for reducing the birth rate. America has given us generous aid to carry on the fight on the first front. We want your great scientific, technical and medical knowledge and experience to wage an equally effective war on the second front. It is only when the conscience of the people has been roused that the war will be successfully waged.

Speaker: ALDOUS HUXLEYAUTHOR

I THINK it is one of the frightening facts of the modern world that we see these appalling subrational drives of aggression and militarism and nationalism being implemented by the most advanced technology produced by systematic reason. So that I would answer Doctor Dubos' question by saying that both these states - the sleep and the dream - are equally dangerous, and that somehow we have to temper the dream with this element which he himself was speaking about yesterday when he quoted the saying of Montaigne that Science sans conscience n'est que rien deI'ame. Science without conscience, without the barriers of compassion and the heart, is the ruination of the soul; that we have to work all the time as entire human beings, not as subrational creatures, and not merely as rational creatures, but as creatures acting from the totality of the soul-body-spirit.

And now let me say how touched I am by what the Ambassador said about wishing that I had not abandoned poetry. Well, I'm afraid the reason I abandoned it was that I simply don't have what it takes. I would like nothing more than to be a poet, but unfortunately I do not have that special gift. I'm a moderately good versifier, but not much beyond that. And let me point out that even if I were a very great poet - even if I were Shakespeare - I would probably find it virtually impossible to write about the subject which we are talking about tonight. I really would defy Shakespeare to write a sonnet or a tragedy about the population problem.

This is really a very serious problem. Here we are faced by something which, as Ambassador Chagla pointed out, is, next to the hydrogen bomb, the most important issue of our time, and we as artists - the people whose business it is to reflect the world and pass on ideas to people at large - we simply cannot do anything about it, because this kind of subject matter is simply unsuitable both to the lyric and to the drama, and even to the novel. I very much doubt whether even Sir Charles Snow could make much of a novel about the population problem. And this is a most unfortunate thing inasmuch as we see that one of the most important issues of our time is actually beyond the scope of those people who should be telling the world how serious the matter is....

Now, to get down to my subject... let me begin with a few figures. The Ambassador gave some of these figures. I will take the figure which deals with the time that it takes for a population to double. Demographers tell us that the population of the planet at the time of the birth of Christ was probably about 250 million - that is to say, less than half of the present population of China. When the Mayflower landed on these shores, the population was about 500 million. That is to say, it took 1600 years for 250 million to double their number on this planet.

Today we have approximately three thousand million inhabitants and as demographers have shown us, by the end of the present century - in about forty years, we shall probably have six thousand million. So that we see, whereas a relatively short time ago it took 1600 years for a very small population to double, it now takes less than half a century for a gigantic population to double. And this obviously shows us what underlines the fact that many people have touched on in the course of these discussions, that we are faced with an entirely unprecedented situation....

I was struck this afternoon by what Dr. McDermott said about the inefficacy of public health measures in regard to the reduction of population. Quite indubitably it had an immense effect upon the increase of population in Europe and this country. It is, after all, only within the present century that the over-all rate of population increase in the world reached 1 % per annum. And the European increase is undoubtedly due, to a very considerable extent, to the application of public health measures. It's extremely simple, and cheap, to apply some elementary public health measures, even to extremely backward people. Two years ago I was in Brazil and the Brazilian Government put a miniature transport at our disposal and flew us up into the jungles of Mato Grosso and set us down at an airstrip belonging to the Indian Protection Service (they have an admirable Indian Protection Service in Brazil), where we came across a literally Neolithic tribe - a tribe of savages who had not yet invented pottery or agriculture, who wore absolutely nothing (they are one of the few tribes of the world who go about stark naked), who live mainly by shooting fish with bows and arrows, and I noticed that these people all had vaccination marks on their arms.

This, of course, leads us to one of the major ethical problems of our time. We've been told for many, many years that a good end does not justify bad means, but in this particular concept we find a paradoxical situation that may lead, among other things, to a very bad end. There's this tragic thing, that we do what is obviously intrinsically good - save people from malaria, save people from smallpox, and so on - but then we find we keep many more people alive and that their last state may be worse than the first. What is the answer to this problem? Obviously we can't stop health measures. We can't refuse to give these people protection against horrifying diseases.

The only answer, it seems to me, is that science should take one further step, exactly as Ambassador Chagla has suggested, and attempt to bring into balance the birth rate with the death rate. And here in this whole problem of ethics, I think it would be very important to bring up children with the idea that many of the ethical principles of civilized life do go right down into these worlds of non-human nature. After all, the Golden Rule goes clown into the world of inanimate nature. "Do as you would be done by." If you want nature to treat you well, you must treat nature well. If you treat nature in such a way that erosion sets in, nature will treat you extremely badly. And in the same way the whole idea of Greek morality - the idea of balance, the idea of moderation, the idea of nothing to excess — is really paralleled by the natural system of checks and balances which goes throughout the whole of animate life and nature. The system of checks and balances is enforced by nature in ways which we cannot accept. They're enforced by mutual devouring and by disease and famine, and our problem is to find humane equivalents for these checks and balances in order to produce this state of equilibrium, which is the natural condition under which animal species can live and under which alone they can live satisfactorily....

Now let us come back to the consequences of the rather rapid population increase which is going on in this country. One of the consequences, as Professor Spengler of Harvard has pointed out, is undoubtedly that the rise in the standard of living will certainly not be as great, in consequence of the population increase, as it would have been had the increase been less substantial. A great deal of the resources made available by increased productivity will simply have to go as part of the replacement of obsolete, houses and instrumentation, and also simply to satisfy the needs of the new population which has come into existence. Then, there is another very serious and difficult problem. It is the problem of education. The difficulties we've already seen in the last few years - the overcrowding of schools and insufficiency of teachers, the fact that in many elementary schools there had to be several shifts of the children; and what we're going to see in the 60's is the same thing happening on an even larger scale in the high schools and universities....

Another peculiarity which this increased population will have in this country, and indeed in most countries, will be this: the great increase of population will be in the cities. There will be an enormous increase in urbanization and something like three-quarters of all the inhabitants will live in cities of more than one hundred thousand, and some immense number (I forget what it is) will be living in one or another of the ten super cities which demographers have seen for the end of the present century. It's worth while enumerating what these super cities will be and what numbers there will be. There will be a super city in Florida at Miami-Palm Beach of about nine million; there will be a super city at Washington-Baltimore, also about nine million; there will be an eight million city around Philadelphia; there will be a 23 million super city of New York; about an eight million super city of Boston; there will be a baby super city around Cleveland of only about six million; about ten million around Chicago; twenty million around Los Angeles; and about eight million around San Francisco.

You may well ask what sort of effect will this immense increase in urbanization have on the quality of individual life? Only too frequently people talk about increases of population solely in terms of the available food supply. The United States will certainly have plenty of food for a good time to come. But after all, it has been said that man does not live by bread alone; he has to live by many other things. And the question arises - what quality of life will there be in the heavily congested urban areas? I, myself, feel it already. It seems to me extremely bad for children to be brought up in these immense urban areas where they are totally out of touch with nature....

Then, of course, numerous sociologists and psychologists have spoken of the strange psychological effect of living in these great cities, which have no real community sense at all. Baker Brown Nails, for example, has written on it; Arthur Morgan has written on it; David Riesman in TheLonely Crowd has written on it; Erich Fromm has written on the same theme. I think some of these complaints may be exaggerated, but nevertheless it does seem quite likely that this bringing-up in totally non-natural conditions, with atomized individuals in only a functional and not in a personal relationship with one another, may produce very serious psychological effects....

In recent years the F.A.O. has reported some evidence that in certain countries the amount of food and goods available to individuals today is actually less than it was forty years ago, and quite recently UNESCO published figures showing that in spite of the immense efforts which are being made all over the world to combat illiteracy, the absolute number of illiterates is greater than it ever was before. Here, again, we see a picture of running as fast as possible in order not quite to stand in the same place....

When we look at this situation and ask ourselves what is to be done, we see that, in fact, there are only two alternatives: one is that the underdeveloped country that wants to develop and raise its standard of living must be supplied with capital from the outside, from countries which have a surplus of capital; or, alternatively, they must do what the Ambassador of India is trying not to do (and thank God is trying not to do), make use of forced labor as capital, because you can use human beings as expendable counters in lieu of capital to a very considerable extent. And the great problem which confronts the world is whether the underdeveloped countries can achieve this improvement in their way of life without resorting to this substitute for capital, which is totalitarian control and the forced labor of the masses....

Lord Orr is probably right in saying that there is about a 50-50 chance of getting over this terrible problem of raising the standard of living without resorting to forced labor. Of course, even under the most favorable circumstances it's not at all certain that there will be a success, and I think that what we shall see is this Alice Through the Looking Glass picture of desperate running resulting only in standing the same place....

Needless to say, this state of affairs is likely to have very serious political consequences. With the frustration of the extremely high hopes with which all the newly independent nations have come into existence, there will grow up a sense of horrible disappointment. I think the consequences of this will be social unrest at home and intense envy and dislike of more fortunate nations abroad, and in certain circumstances a tendency toward aggressive action toward nations held to have greater resources than the ones feeling this pinch of frustration. And it's worth while pointing out that we are discovering now that it is perfectly possible for an underdeveloped country, provided it gets a certain amount of aid from abroad and provided it can impose forced labor upon its millions, to remain a country mainly peopled by men and women on a subsistence level and yet become a first-rate military power. It is possible to put the entire emphasis of industrial development into heavy industry and the creation of armaments. And this possibility, which I don't think was ever understood or realized until quite recently, poses an appalling fact, particularly in the context of the Cold War. And nobody has any idea of the consequences it may have.

Now, finally, what can be done? Speaking of the matter in ethical terms, you can ask the question: How can biological effects be reconciled with such a humanitarian ideal? Can we find humane and acceptable substitutes for nature's method of balancing non-human population by means of hunger, disease and (among certain species of ants and among human beings, as these are the only creatures that make war) also by war. Can we find these more humane substitutes? This is the problem.

Now, quite obviously, two things can be done. One is to do everything possible to increase production, of both food and industrial resources. It is quite obvious that while the more prosperous parts of the world are spending about a hundred billion dollars a year on armament, the problem of the underdeveloped countries cannot be solved. I would like very much to see a Gallup Poll conducted among all the inhabitants of the earth, asking the question: Which do you prefer - to have enough to eat or to have nationalism and armies? And I think that if this question were honestly asked, I think the majority would say that they probably prefer to have enough to eat. But it would have to be stressed that they're not going to be able to have both. I don't think they are going to be able to have both. And as long as the nations, in the words of Lord Orr, remain insane, it's very unlikely that this 50-50 possibility of solving the overpopulation problem will be realized. Then, it is quite clear that whatever efforts are made to increase production, they will never, if the rate of increase continues indefinitely as it is, be sufficient to catch up with the enormous increment of human birth over deaths, and therefore it will become necessary, as the Ambassador pointed out, to introduce some system of birth control....

But when you come to, first of all, the problem of increasing p roduction, and then the problem of decreasing the birth rate, you find that you are up against the problem of educating enormous numbers of people. To increase the production of food you have to educate millions of peasants, change their habits and introduce new forms of technology. And in order to change the reproductive habits of a great number of people, you have to have an educational campaign. It is perfectly obvious that this is an extremely difficult and arduous problem, but unless it is faced and faced with some degree of success, we shall see, as Lord Orr said, chaos in the world within 50 years. We shall probably not see it before then. But, as has been pointed out on several occasions in these discussions, it becomes increasingly necessary for us to become aware of the remoter future and to do something about that future.

And clearly, what is required, as the Ambassador points out, is, if possible, the production of an oral contraceptive or what is called in popular language "the pill." But unfortunately the production of the pill and the administration of it is a multiple problem. It is first of all a problem in chemistry, then it's a problem in medicine, then it's a problem of psychology, sociology and education - and even in theology. So that we have to attack this problem on many fronts at once. And incidentally, the pill isn't here! The only oral contraceptives that are here are very expensive, have to be taken every day, and have unpleasant side effects in many cases. So, that we are still quite a long way away from this ideal method of family planning.

Another thing that has to be remembered is that even if we get the pill and even, if by some miracle the birth rate were reduced overnight, say by 20%, there would still be in the next generation or so very formidable increases in population for the simple reason that the number of people in the reproductive age group is so very great at the present time. Even if their birth rate were 20% less than the birth rate at the present time, this great number would produce vast numbers of children. So nobody must imagine that this campaign of family planning is going to produce immediate results. It will not produce results, probably, in less than about a generation.

But unless it is adopted, the consequences (and I think most demographers would agree) will be completely disastrous. And here we have to remember that time is against us. We have to act with the greatest possible speed in this matter, otherwise the future fate of mankind may be completely disastrous and we shall then see what Lord Orr calls "chaos" and what I would call, in the context of this talk, a serious deterioration of the whole quality of human life due to this breakneck increase in quantity.

Dr. Dubos: This is my last occasion to appear before you as chairman of this conference, and I should therefore take occasion of these few minutes to thank Dartmouth College for having organized a meeting which unquestionably has been stimulating to all the participants and we hope to all of you. But I should also try, not to summarize what has been said, but to tell you some of my personal reactions to it. But to do this as chairman of the conference would demand that I be able to be objective and detached, and I can assure you I am not an objective person. I always take sides. . . .

This afternoon, at the end of the panel, there came to me many representatives of the medical press and of the Boston and local press. And they were very much puzzled by the fact that out of our discussion this afternoon there did not arise any clear conclusion - something that could be stated as a set of beliefs on which all of us agreed. And I couldn't be more in agreement with them. There sure was nothing that we agreed on. And I tried to make clear to them that this was the very purpose of our meeting; that we are not assembled here to solve problems. Our purpose is to air problems. Our purpose is to learn to state our problems and to state them as clearly and thoughtfully as we can, so that they can be better analyzed by the scientific community and so that the community at large - lay people - can struggle under our guidance to form its own opinions, often to be based on judgment of values.

Now this is a very difficult task for the press and the lay public. If I were to illustrate how difficult it is, even when each and every one of us tries to tell the truth as we see it, I need only take one example. And here I abandon any pretense of objectivity. You may have noticed that this afternoon Dr. Walsh McDermott casually made the statement that, "After all, it is not proven that medical technology has been as influential as people believe in bringing about the increase in population that we see all over the world." I now and then hinted at such things. Now you have seen the result: Dr. McDermott was qualified in the most dignified form of English language with the word "blarney."

Now, it happens that there were on that panel two members from the field of infectious disease, Dr. McDermott and I. We are the two specialists. Both of us, specialists, do not believe that medical technology is the main factor responsible for this increase in population, and the rest of the panel does not believe us. Or perhaps it is not the rest of the panel but is merely an expression in disguise - an expression of that very profound suspicion of the wisdom of scientists, which is prevalent all over the world, and even among the most distinguished thinkers in the world. . . .

I should like to continue in my French pattern, not aschairman of the committee, to quote one of the panelists this morning, who said that not so long ago it used to be thought that there is something peculiar, something unique to man, that makes man different from the rest of creation. And the way he said it, there is no doubt that in his mind, and he tried to convey to you his conviction, that now we are much wiser and much more learned and that we no longer believe that there's something unique to man.

Well, ladies and gentlemen, in my opinion if you start from the assumption that there's nothing peculiar to man, we have been wasting our time. Because what we have been talking about is not a kind of statistical morality that applies to living things at large. It's a kind of statistical morality, and a kind of individual morality, that has meaning only if we are referring to man as a very special living thing. I am not pretending for a minute that there is any scientific evidence that man is unlike the rest of living things. But certainly, in the most pragmatic sort of way, in an operational sort of way as a scientist, I know full well that each and every one of us has thought and has acted as if man were something peculiar, because if he were not, what Dr. Warren Weaver discussed about statistical morality, where he introduced a one-to-ten-million chance, would not apply at all.

There is, ladies and gentlemen, in my opinion, something peculiar to man and I think that if there has been any difficulty in our discussion during the past two days, it is that we have never been quite willing to say very forcefully that what we are speaking about is not just about living things but about man - whether man is something very special because of some act of Divine Creation, or whether man is something very special because we, being men, have so decided. So whatever happens tomorrow, I do hope that each and every one of us keeps clearly in mind that what we are talking about is not about life, not about living things, but about man who has created human civilization.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIt Was A Dartmouth Jinx All the Time

November 1960 By AMOS N. BLANDIN '18 -

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Year in France

November 1960 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Feature

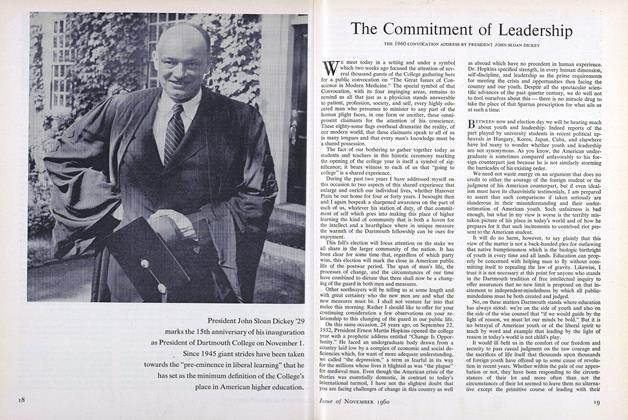

FeatureThe Commitment of Leadership

November 1960 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

Feature"The Era of the Shrug"

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleSecond Panel Discussion

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleFirst Panel Discussion

November 1960

Article

-

Article

ArticleSCHOLARSHIP OF THE COLLEGE

April, 1912 -

Article

ArticleL. D. WHITE '14 REAPPOINTED AS GUGGENHEIM FELLOW

APRIL 1928 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah!

June 1954 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

October 1992 -

Article

ArticleA Tribute tO W.F.T

April 1939 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS '01 -

Article

ArticleTEACHING IN VACATIONS

DECEMBER 1929 By Professor Edwin J. Bartlett