CLASS OF 1926 FELLOW, SENIOR FELLOW

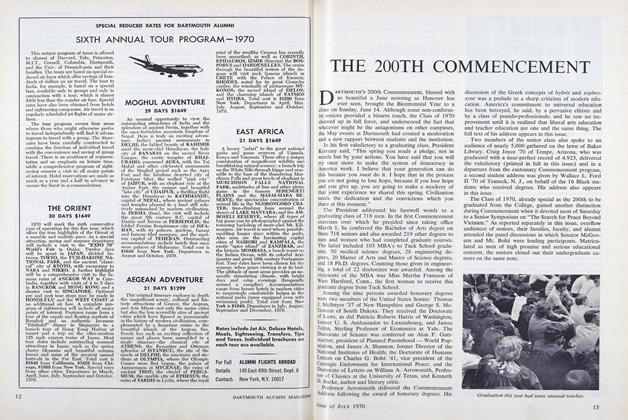

UNDER the Class of 1926 and Senior Fellowship programs, I had the opportunity of spending the past summer and fall working with a teen-age gang on the streets of the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Having been employed as a Street Club Worker with the New York City Youth Board, which is the City's official agency for the prevention and control of juvenile delinquency, I was able to gather a first-hand account of the pattern of delinquent behavior manifested by a small, anti-social group. The Dragons, the street gang to which I was assigned, provided excellent source material for the fascinating and challenging empirical research project which I had chosen.

Since the newspapers in almost every section of the country gave comprehenseve coverage to the bloody street warfare on the Lower East Side during the past summer, it would be superfluous to review here the series of unfortunate tragedies resulting from the inter-gang conflict. Instead, I consider it more appropriate to inform the reader about the particular type of work I had to perform and perhaps reflect upon some extremely interesting personal experiences. In this way, the reader will be acquainted not only with some aspects of my work but also with the phenomena of delinquency itself and some of the methods utilized by the City of New York to deal with the problems of anti-social youngsters.

It is important to examine the Youth Board's philosophy on anti-social teen-age gangs in order to fully appreciate the rationale for the role of Street Club Worker. Let's take a look at some of the principles developed by the Youth Board staff as a basis for their work with street gangs.

Social scientists would generally agree that participation in a street gang, or club, like participation in any other natural group, is a part of the growing-up process of adolescence. However, the average teen-age gang member differs in many significant respects from the normal adolescent. Although the gang member certainly has needs which are common to all normal youngsters, these needs are often highly intensified by the pressures of life in his neighborhood, his home, and his general environment.

The gang member joins a group of his fellows, or "peers," most of whom have similar backgrounds; so does the average teen-ager. However, because of the pressures, the deprivations, the group for the troubled youngster becomes all too often his only outlet. As a member he gains almost the only satisfactions out of life possible to him. Furthermore, the group as a whole, having few skills, little sociability, and less direction and guidance, attempts to gain stature - to be important - in the only way it can: by fighting and winning, by doing things which are not acceptable to society, by being the "baddest."

In some way, then, it devolves upon us to sublimate the energies of these youngsters into more constructive channels. Accepting the gang as a reality and working within the framework of the natural group structure, we must somehow reach out to these young gang members and help them achieve in more socially acceptable ways the recognition, status, and emotional fulfillment they so desperately need and crave. We must make them aware of their responsibilities not only to their families and the community but also to themselves. Their horizons must be broadened, individual personal and social adjustments must be improved, and democratic participation within the gang itself must be encouraged.

How is this done? The Youth Board's Street Club Project "reaches out" to teen- age gangs by sending workers - "Street Club Workers" - directly to the gangs themselves. The worker, who is assigned to one particular gang, works wherever his group may be. There is no central community agency involved; the gang members do not come to the worker.

Of course, in any specific neighborhood where there are several "bopping," or fighting, gangs, one Street Club Worker must be assigned to each of the existing groups there. This principle, called "saturation," is one of the most important concepts behind the Youth Board's street club work; for to service just one gang in an area where conflict may arise between two or three fighting groups . would unquestionably prove to be useless.

I would regard as the primary goal of the worker the achievement of such a real, sincere, and meaningful relationship with the gang and its individual members that, in time, he will be able to influence the group for the better. This, naturally, cannot be accomplished in a short time. It takes years of hard work, tolerance, and intelligence to rehabilitate an anti-social street gang. Even then, success is never guaranteed.

Recognizing the fact that my tenure with the Youth Board was only temporary, the supervisor of my unit wisely decided to assign me to a fighting gang that was already being serviced by another worker on the staff. In this way, I did not have to face the problem of locating the group myself. Also, the process of making contact with the gang was appreciably accelerated. My major trouble started as soon as I attempted to gain the acceptance of my group.

Even though the other worker explained to the members of the Dragons that I was performing a job exactly similar to his, the youngsters remained uncomfortably suspicious in my presence. Gaining the gang's acceptance was a slow and painstaking process which deepened only through testing and retesting.

For almost the first month of my contact with the Dragons, the boys were intensely suspicious of me. Some of the members were absolutely convinced that I was either a "cop," F.B.I, agent, or some other undercover police official. During this time, no verbal assurance from me was effective in changing their opinions. The fact that the Dragons were actively engaged in a conflict, or "rumble," with the Sportsmen, another Lower East Side gang, and were under close surveillance by the police obviously aggravated the problem of gaining acceptance.

Nevertheless, by the second month on the job I recognized definite signs of being slowly accepted. For example, I knew I had some of the gang's confidence when the boys began to recount in my presence specific information about their present and former anti-social activities. Subsequently, when many of the youngsters involved me in intimate discussions about their families, girl friends, their hopes and their troubles, I knew that they believed in my legitimate role with the Youth Board.

At the point when the relationship had been fairly securely established, I was able to interpret fully my particular position with regard to the group. I emphasized that I liked the group very much and genuinely wanted to help them, but I explained that my work compelled me to report to the police any knowledge of their possessing weapons or planning to "go down on," or attack, their immediate enemy, the Sportsmen.

It might be thought that my explanation of the duty of informing the authorities would destroy whatever confidence the gang had in me. On the contrary, it definitely did not; and it could even be argued that the newly defined relationship provided some very real benefits to the members of the gang. It will not be at all difficult to explain why this was so.

In retrospect, it seems to be an incontrovertible fact that almost every member of the Dragon gang with whom I made contact was unquestionably afraid of taking part in a gang fight. Nevertheless, not one youngster ever did, or could, express openly to the group his very real fear of fighting. "Punking out," Or staying out of a fight because of fear, was considered by the group to be an unpardonable violation of their code. Consequently, the only way in which a youngster could assure himself that he would not have to fight was to approach the worker privately and reveal to him that there was going to be a "bop" at a certain time in a particular location. There was, therefore, no loss of "rep," prestige or reputation, within the group as a result of his confiding this to the worker. In addition, the false bravado of the group could continue unblemished and unchallenged.

The utility of such a relationship described above is supported by the fact that in the summer of 1959 (according to figures published by the research department of the Youth Board) there were 425 reported contacts by Street Club Workers in New York City with the police who were subsequently responsible for averting what otherwise would have been tragic teen-age terrorism.

As I mentioned earlier, during the time that I was assigned to the Dragon street gang they were actively engaged in a conflict situation with their traditional neighborhood rivals, the Sportsmen. Consequently, much of the work I was required to do during the summer involved helping arrange some resolution of the problem of constant inter-gang warfare.

Recognizing the fact that most of the members in both gangs really preferred to stay away from the dangers of daily gang fights, our staff contacted the leaders of both the Sportsmen and Dragons and suggested that they get together at a Youth Board-supervised mediation meeting. At this session, it was explained, both sides could present their sides of the story and perhaps agree on some kind of peace settlement, the provisions of which could be entirely determined by the gang leaders themselves. After a series of initial setbacks, the staff was successful in persuading the leaders of the two groups to agree to a meeting.

Before entering the building which our staff had chosen for the meeting, each one of the five representatives from each of the two groups was searched thoroughly. I was delegated to search, or frisk, the Dragon members. It immediately became clear that the "shake down" methods employed by our Hollywood actors in gangster films are woefully inadequate in real life, for although the youngsters proved to be unarmed, they were quick to point out that my cinema technique was quite ineffective. Fortunately, the occasion for using a weapon did not present itself during the evening.

In a manner that was surprisingly parliamentary, the two groups of leaders thrashed out the history of their three- year conflict with each other. The story that evolved from their discussion is testimony to the often ludicrous conditions that occasion many inter-gang wars.

It seems that a third group of youngsters who had called themselves the Viceroys started fighting the Dragons several years ago. Since the Viceroys lived in a section of the Lower East Side which was located next to the Sportsmen "turf," or territory, the Viceroy leaders requested that the latter join them in their struggle with the Dragon street gang. After a series of initial protestations by the Sportsmen that they were not interested in fighting everyone's battles, they were ultimately convinced that only in the union of the Sportsmen and the Viceroys would there be some safety in their territories. Subsequently, the Sportsmen began to fight the Dragons.

Shortly thereafter, the Viceroys engaged in a street fight as a separate group. During this "rumble" several of the Viceroys fatally injured a boy from the opposing side, not the Dragons in this particular instance. The police summarily arrested and incarcerated the Viceroy members responsible, and the gang as a unit slowly disintegrated. In a matter of months, there was no indication that a group of Viceroys existed in the neighborhood. Nevertheless, the Dragons had developed a hatred toward the Sportsmen as a result of the recent struggle with them and the Viceroys. Here was a perfect case where a group, namely the Sportsmen, was left holding the proverbial "bag."

With the passing of time, the two groups continued to fight, but almost no one could remember exactly why. Soon, however, each battle became a virtual caususbelli for a return match. Apparently, this was the situation up to the present.

When the facts were made clear to both groups of representatives, it was not difficult to persuade them that their present animosity toward each other was ridiculous. After a brief discussion of terms, each side agreed to sign a peace treaty and thereby resolve the senseless gang wars between the two groups.

One by one, each of the ten gang members signed his name to the treaty. Some had difficulty in writing their names, and one seventeen-year-old boy, after signing the treaty, even . exclaimed, "Man, like now I feel like General Custer at the Alamo!" The historical validity of this personal impression is, of course, highly questionable, but the fact remains that it was uttered in a way which reflected a complete change in attitude taken by both sides. Fortunately, for both the individuals concerned and the community as a whole, there has not been even one act of violence committed by a member of either gang upon a member of the other since the day of the agreement. And all the kids admit that it's better this way.

I have described one instance in which intelligence, perseverance, and concern were all responsible for the resolution of what had previously been considered an insoluble problem of delinquent gangism. The experience which my internship with the New York City Youth Board afforded me leads me to believe that the approach taken by this city-financed agency, which is admittedly far from perfect in either its organization or operation, is nevertheless an extremely effective step forward in the attempt to deal competently with the problem of juvenile delinquency.

In concluding, I would like to express my appreciation for having the opportunity of consummating, so to speak, my studies at Dartmouth College with an invaluable personal experience. It was an inestimable part of my education.

The author with some members of the Dragons, the gang with which he worked closely all last summer and fall as a temporary Street Club Worker with the New York City Youth Board.

Postel talking at night with gang members onthe corner of Henry and Gouverneur Sts., aspot within the territory of the Dragons.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureProfessor Jesup's Herbarium

March 1960 By JAMES P. POOLE -

Feature

FeatureFraternity Discrimination Faces a Deadline

March 1960 By THOMAS E. GREEN '60 -

Feature

FeatureAre Marriage and College Compatible?

March 1960 By MARGARET MEAD -

Article

ArticleThe Mission of Liberal Learning

March 1960 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1960 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, ROBERT FISH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

March 1960 By RICHARD W. BALDWIN, IRA L. BERMAN

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHE 200TH COMMENCEMENT

JULY 1970 -

Cover Story

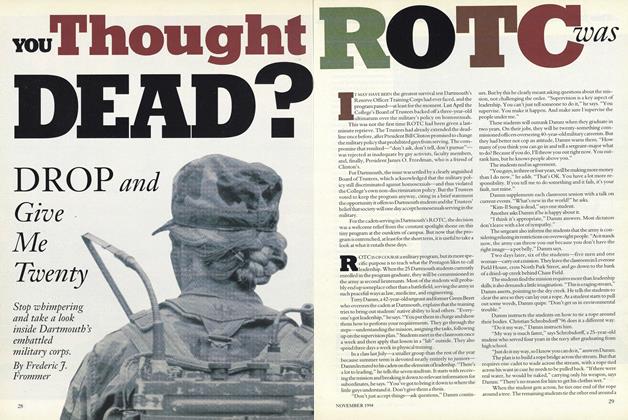

Cover StoryYou Thougnt Rotc was Dead?

November 1994 By Frederic J. Frommer -

Feature

FeatureThe Image of the Educated Man

July 1960 By HARRISON CASE DUNNING '60 -

Feature

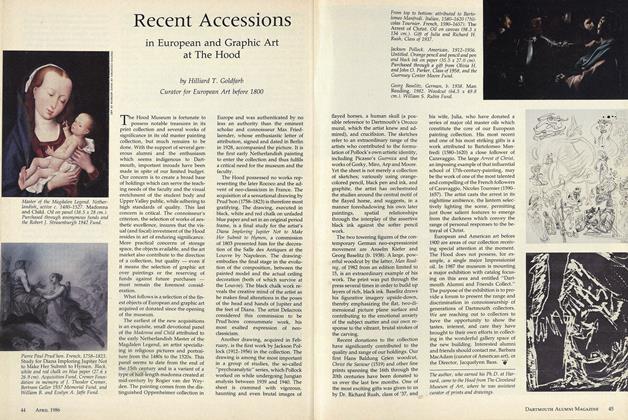

FeatureRecent Accessions in European and Graphic Art at The Hood

APRIL 1986 By Hilliard T. Goldfarb -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Bunch Of Characters

JANUARY 1997 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report THE 1955 ALUMNI FUND

December 1955 By Roger C. Wilde '21