An important aid to student and teacher is the little known botanical collection honoring the late Prof. Henry Griswold Jesup

PROFESSOR OF BOTANY, EMERITUS

MR. WEBSTER, not Dartmouth's Daniel but Yale's Noah, defines an herbarium as "a collection of dried and pressed specimens of plants usually mounted or otherwise prepared for permanent preservation and systematically arranged." Or the word can also be applied to "the room, building or institution in which such a collection is kept, or to which it belongs."

That definition is cited for the benefit of any reader who may have little or no understanding of what an herbarium is, and this article is written because it has increasingly come to my attention that there are those in the Dartmouth community, even some faculty members in the science departments, who are not aware that there is such an institution on the campus.

The herbarium at Dartmouth is housed in a number of steel cases in one of the larger rooms on the second floor of Silsby in the domain of the Department of Botany. It is composed of two collections, the Jesup Herbarium with over 55,000 specimens of ferns, conifers, and flowering plants, and the Lyman Herbarium with about 5200 specimens of the lower forms of plants such as mosses, lichens, fungi, and algae.

A publication with the title Index Herbariorum, a register of the herbaria of the world, lists over 1100 herbaria of recognized standing. Included are about 150 in the United States which contain 10,000 or more specimens. Among the largest collections in this country it lists the U.S. National Herbarium in Washington, D.C., with 2,700,000 specimens, the New York Botanical Garden in Bronx Park with three million, the Gray Herbarium and associated herbaria at Harvard University with about three and a half million, the Academy of Science in Philadelphia with a million, and the Chicago Natural History Museum (Field Museum) with about two million specimens. In addition many state universities maintain large herbaria.

Of the various branches of botanical science one of the most fundamental is taxonomy, which is concerned with the identification and classfication of plants, and an herbarium is the principal tool of the taxonomist. After plants for an herbarium have been pressed and dried for preservation, each is mounted on a sheet of heavy paper by means of strips of gummed tissue, plastic strips, or other adhesive. Its identity is indicated by an attached label on which is recorded its Latin or scientific name, the date and place of collection, the name of the collector, the name of the person who identifled it and, preferably, additional information as to the habitat in which the plant grew.

After proper preparation the specimens are filed in the herbarium cases in accordance with their classifications into such large groups as ferns, conifers, and flowering plants, and within these categories into families. These groups are arranged according to some accepted system of relationship. The lesser groups within each family, such as genera, species, and variety, are filed in heavy manila folders either according to phyletic sequence or sometimes in alphabetic order. Whatever system is adopted, the important principle of arrangement is to make it a simple matter to locate any group or any specimen. Most herbaria are largely composed of wild plants, although in certain institutions concerned with horticulture or floriculture, herbaria of cultivated plants are maintained.

The Jesup Herbarium was named in honor of Henry Griswold Jesup who was appointed to the Dartmouth faculty as Instructor of Botany in 1876, and in the following year was named Chandler Professor of Natural History. He was born January 23, 1826 in Westport, Connecticut. After early education in private boarding schools, he entered Yale and graduated with an A.B. degree in 1847. After two years of travel and teaching in Georgia, he attended Union Theological Seminary. Following his graduation in 1853 he began preaching in Stanwich, Connecticut, and was ordained and installed as pastor of the Congregational Church the next spring. He resigned his pastorate in 1863 because of poor health, and after a year of residence in Minnesota located in Amherst, Mass. He resided there until the time of his appointment at Dartmouth.

I have found no record of just how he made a living during those fourteen years at Amherst, but his carefully prepared and accurately named herbarium specimens collected during that period indicate that he had achieved a good training in taxonomy. Clark L. Thayer, Professor of Horticulture, Emeritus, at the University of Massachusetts, has very helpfully called to my attention a volume published in 1875 with the title, A Catalogueof Plants Growing Without Cultivationwithin thirty miles of Amherst College by Edward Tuckerman, Professor of Botany, and Charles C. Frost, M.A. In the preface, following several acknowledgements, Professor Tuckerman writes, "and, last but not least, to Rev. H. G. Jesup of this town, who has recently gone over the larger part of the ground afresh, with unsurpassed care, and added, as these pages show, a very considerable number of new things. It is to the same gentleman that the College owes the foundation and the building up of its new North American herbarium." The "new things" were plants collected by Jesup which had not previously been recorded for the region. There is no record that Professor Jesup at any time had any official connection with Amherst College.

Professor Jesup remained as a resident of Hanover until his death on June 15, 1903. He retired from the faculty in 1899 because of poor health, although he was over 73 years old at the time. It is evident from his earlier retirement from his pastorate, and from occasional excerpts from his correspondence, that he was never very robust, and that he carried on his teaching duties under this handicap. One of his letters, written in 1894, is concluded with the sentence, "Wish I might do as the Sea-slugs that can throw out their old stomachs from time to time and get new ones." Even in his later years of teaching, however, he was still able to do some botanizing. In the late summer of 1895 he wrote, "In order to see if I could get some strength for my autumn work I accepted an invitation from Balch '94 to visit him in Jonesville. He took me to Mt. Mansfield with his own horse . . . though it was a fatiguing jaunt I was much benefited. The air was so bracing that with Balch's air I climbed to the nose and afterwards went to the chin."

In December of the following year he wrote, "I now wish my health were better and I was twenty years younger. Dr. Tucker is ambitious to enlarge the Biological Courses and give them the chance that they have never had before." In February 1895 he wrote, "It is not easy for me to give up but I suppose that I must acknowledge the fact that I have reached a point where the little vigor I once had is largely gone." He continued to teach through the spring and summer of 1898, however, but in March of 1899, the year in which he retired, he wrote from the hospital in Hanover, "I am again in the Hospital and have been here a month or more. I fell down in the street one night going home from supper with what I suspect was a slight paralysis." His later letters indicate that his teaching days were over by the time he was taken to the hospital, and that he was unable to carry on his activities, even in his herbarium, to any great extent thereafter.

In the Chronicles of the Class Day exercises in the eighties, Professor Jesup is sometimes referred to as "Auntie Jesup." From those who knew him, however, I learn that he was not an effeminate person. He was slight in stature, somewhat prim in bearing, and he never married. The sobriquet "Auntie" may have resulted from some of the aspects of his personality, or perhaps it may have been in part due to the fact that he taught botany in a day when that subject was frequently looked upon as more fitting for young ladies in a seminary.

Professor Jesup would merit a niche in the D.O.C. Hall of Fame, if such an institution existed. In an article "Dartmouth Out of Doors in the Eighties" (DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE 16:218-219, Jan. 1924) Charles Sumner Cook of the Class of 1879 writes, "Oddly enough the first advancement in mountaineering during the eight years considered, was due to a man who was totally unfit for any hiking expeditions; for it was Professor Jesup who discovered Happy Hill. The professor was indeed an all-round nature lover, and was interested in all things out of doors, from mountains to diatoms. Unfortunately he was physically unable to tramp about the country, but he was a liberal patron of the livery stable. He had come to know all the interesting features along the roads of the neighborhood as no one else did." After describing his first trip to the hill with Professor Jesup. the author continues, "It was this discovery that gave much pleasure to many of us; and I am still proud of being the first to share this pleasure. Several weeks after the discovery I was stopped on the street by some friend who announced that 'Professor Jesup's hill' had been given a name; and that it was now 'Happy Hill'."

In the resolutions on the death of Professor Jesup read before the Dartmouth Scientific Society, it is recorded:

"He took a deep interest in this society and engaged in its discussions. He was elected to membership, April 18, 1877.... Twice he acted as President in 1880 and 1895.

"He took up the study of Botany first that he might have some diversion in the midst of his bodily ailments. He founded the Connecticut Valley Botanical Society, and was a member of the Vermont Botanical Club and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

"When he ceased to be connected with the department of instruction he presented to Dartmouth College a scholarship to the value of $1200. - Afterwards he bequeathed to the same his Herbarium of Phanerogamia and Ferns — which is chiefly made up of the plants of New England."

In his obituary in the Hanover Gazette of June 19, 1903, he is referred to as "a man of great industry, singularly kindly and generous of disposition, an enthusiastic and successful instructor. Of all the members of the faculty none was more thoughtful and generous in his gifts and words."

In 1882 Professor Jesup published "A Catalogue of the Flora and Fauna within Thirty Miles of Hanover." The list of Vertebrates included under "Fauna" was contributed by Professor T. W. D Worthen, at that time Instructor in Gymnastics and Mathematics, later Cheney Professor of Mathematics. This publication was revised in 1891. In the Report of the Forest Commission of the State of New Hampshire for the year 1885 Henry Griswold Jesup is listed as one of the Commissioners, and a section of forty pages on "The Trees and Shrubs composing the New Hampshire Forests" was written by him. In 1887 he published "Edward Jesup and his Descendants." In the preface he wrote, "The present work was begun in 1879 at the solicitation of Morris K. Jesup, Esq. of New York City, and has been prosecuted during intervals of leisure up to the date of publication, a period of nearly eight years." The records of the Treasurer of the College indicate that presumably Morris K. Jesup contributed to the fund which established the Henry Griswold Jesup Scholarship.

Although Jesup was the first Instructor in Botany to be appointed to the faculty, botany was not new to the curriculum at the time of his appointment. The first mention of such a course occurs in the catalogue of 1822. In the portion devoted to Medical Instruction is listed "A course in Botany commencing in May." Except as a part of the Medical School curriculum the subject was not offered until after the Chandler School of Science and the Arts was established in 1851. In the catalogue for 1852-53 the Chandler School curriculum included a course Elementsof Botany for the summer, term of the junior year. It was first offered in the Academic Course as Natural History-Botany in the 1866-67 catalogue. The New Hampshire College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts was established by an act of the Legislature in 1866. Its location in Hanover was authorized by the Legislature and, by agreement between the Trustees of the two institutions, it became part of Dartmouth College. It opened in 1868 and in the three-year course in Agriculture three botany courses were offered. Botany was not listed as a separate department until 1894. In the catalogue for 1894-95 Jesup was fof the first time listed as Professor of Botany and head of the department.

In the catalogue for 1870-80 under Prizes was the announcement, "Prizes in Botany - Professor Jesup offers two prizes amounting to $20 for the best two herbariums." In 1885 the announcement was changed to read, "Two botany Prizes - 110 to the Sophomore in Systematic Botany who shall present the best herbarium, and $15 to the Junior who shall present an essay, of not less than a thousand words, which shall give the most complete account of the anatomy and physiology of any plant or class of plants as a result of his own investigations." These prizes were continued until Professor Jesup's retirement. This change in wording is interesting as a reflection of the gradual broadening of botany from a narrow systematic discipline to the comprehensive plant science of the succeeding years.

As stated above in the Dartmouth Scientific Association resolutions on the death of Professor Jesup, his private herbarium did not become the property of the College until after his death. The origin of an herbarium at Dartmouth, however, antedates Jesup's appointment. In 1874 Professor Charles H. Hitchcock, Hall Professor of Geology and Mineralogy, and also State Geologist, published the first volume of Geology of NewHampshire. This publication was preceded by a geological survey of the state. In this volume is the statement, "Work has steadily progressed, during the continuance of the survey, upon the Museum." He had reference to a museum being organized at that time, and housed in Culver Hall which was built in 1871. That building, now long gone, faced on East Wheelock Street about opposite where Topliff Hall now stands. It was built to accommodate some of the Agricultural classes, and the departments of Chemistry, Geology, and Natural History. The upper floors were set apart for use as a museum.

In his description of the museum collections, Professor Hitchcock included, "fifth, the plants of the White Mts., collected by the survey, and the local flora of Hanover, the latter gathered and presented to Dartmouth College by Miss Mary Hitchcock." In the College archives is the record that Mary Hitchcock was the sister of C. H. Hitchcock with whom she lived for many years, that she helped in the Botany Department, and that she died in 1899. Baxter Perry Smith, in the appendix of his History of DartmouthCollege, published in 1878, lists the contents of Culver Hall. After listing the collections on the fourth floor, he continues, "In the story below is one room devoted to an excellent herbarium." In the Jesup Herbarium at present there are specimens with the label, "Alpine and Sub-alpine Flora of the White Mts., N. H." The collectors were Wm. F. Flint and J. H. Huntington, and the dates of collection in the 1870's. In Volume I of the Geology of New Hampshire, Chapter XII, The Distribution of the Plants of New Hampshire, was written by Wm. F. Flint. Other specimens now in the Jesup Herbarium were collected by Mary Hitchcock in the early 1870's. Apparently it was these collections which formed the nucleus of the present herbarium.

In the College Museum of today is C. H. Hitchcock's "Day Book or Journal designed to record the donations, and various acts performed for the benefit of the Natural History Museum at Dartmouth College, commencing January 1, 1889, under the Curatorship of C. H. Hitchcock." In this book Professor Hitchcock recorded numerous gifts and pur- chases of specimens, as well as many received in exchange. In the Jesup Herbarium files there is a checklist, printed in 1887, with the species then represented in the herbarium checked off, and also a ledger listing in Professor Hitchcock's handwriting many pages of the names of plants. On the first page is written, "Catalogue of Plants in the Herbarium of Dartmouth College, made out in February 1890, arranged in the order of Bentham and Hooker's Genera Plantarum." George Bentham and Sir Joseph D. Hooker, British botanists, were recognized authorities in systematic botany at that time. In the Hitchcock Day Book is the record, "A census of the Herbarium, June 1890, shows present 3916 species." Through the next few years various purchases and exchanges are recorded, some from foreign countries including New Zealand, Brazil, and Mexico. In 1893 is the notation, "There are 4752 specimens in the Herbarium after revision."

Following legislative action, the College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts was moved to Durham in 1892. Although Hitchcock's Day Book gives a list of geological materials and minerals taken to Durham from the Museum, there is no mention of herbarium material. It seems certain, however, that there must have been some division of the specimens at that time. Professor Albion R. Hodgdon, Chairman of the Department of Botany at the University, has written that when he began his work on the herbarium there in 1930, there was a collection of about 1500 specimens that were said to have been with the "College" since its removal from Dartmouth. Included were collections by Jesup, Flint, and Huntington among others.

For the year 1896-97 is the record, "Additions were made to the Herbarium in the early summer of 1896. .. and the collection then turned over to Professor Jesup. The Herbarium has been moved to the new building." The "new building" was Butterfield Museum built in 1895-96 to house the Departments of Geology and Biology, and the Museum collections. It was demolished in 1928 to make way for Baker Library. On vacating Butterfield, Biology and Geology were installed in Silsby, built just before Butterfield was torn down, and the Museum was moved to its present quarters in Wilson Hall, which had previously housed the library. Professor Hitchcock's Day Book was kept up until his retirement in 1908, but the only other notation with any reference to the herbarium was in June 1897. At that date he recorded a brief statement of the objects in the Museum. Among them he listed, "5000 species Herbarium, and Jesup's private collection of everything in Gray's Manual." Inasmuch as Gray's Manual of the Botany of theNorthern United States, at that time in its sixth edition, included all the flowering plants known for the region covered, this description of Jesup's collection was clearly something of an overstatement.

Professor Jesup's private herbarium was evidently kept in his own living quarters during, his first years at Dartmouth. In the herbarium files is a printed checklist with Jesup's name and "Catalogue of the Herbarium, 1874" written on the cover in his own handwriting. On the inside of the cover he wrote, "This herbarium was saved uninjured from the fire which occurred Feb. 1, 1881 and consumed the dwelling in which it was at that time. Its present existence is a memorial of the prompt and energetic action of the student-friends of the owner, and henceforth has attached to it a double value." Below this statement he wrote, "There must be 4000 sheets." As to whether he moved his plants to Culver Hall after that fire, there is no available record, but it is clear that they were in Culver by 1895. In February of that winter, Jesup wrote one of his former students, "When I last wrote I promised a few additional notes when the weather so moderated that I could get at my herbarium in Culver Hall."

When moved from Culver to Butterfield Museum, the herbarium was stored in wooden cases in the basement. Due to Professor Jesup's enforced inactivity, and his retirement in 1899, it apparently received little care. The cases were not insect- or dust-proof and, even more unfortunately, they were located where the specimens were subject to damage by steam and drip from pipes. Mounted specimens were perhaps used to some extent in teaching, but bundles of unmounted material remained in quite unprotected storage, a prey to molds and insects for the next thirty years.

When Silsby was built a room was designed for the herbarium and modern, insect- and dust-proof, steel herbarium cases were installed. The resuscitation of the herbarium from that time on stands to the credit of Professor Arthur H. Chivers who graduated from Dartmouth in 1902 and, following graduate work at Harvard, returned to teach in the Department of Botany in 1906. Under his direction, during the decade following the move to Silsby, the specimens from the College Herbarium and from Professor Jesup's private collection, together with several other collections which had accumulated, were incorporated to form the herbarium to which the name Jesup Herbarium was then given.

One of the important accessions was received as a gift from Willard W. Eggleston who graduated from Dartmouth in 1891 and eventually became a government botanist in the Bureau of Plant Industry. He was a student under Jesup and one of the winners of the Jesup Prize during his undergraduate days. The excerpts from the Jesup correspondence previously quoted are all from letters preserved in the Eggleston file in the Baker Library archives. Mr. Eggleston's work entailed visits to many parts of the United States, and his collections, together with specimens which he accumulated by exchange with other botanists, constituted a very valuable addition, both in number of species and in geographical distribution. Part of his herbarium was sent to the Botany Department in 1929, and the remainder some time after his death in 1935. In addition, in 1930, he contributed $50 toward the preparation of his specimens, and in 1940 Mrs. Eggleston presented to the College a fund of $2500, the income to be used for two Willard W. Eggleston Memorial Prizes to be awarded annually by the Botany Department for student treatises on original investigations, with the additional provision that any surplus might be used for the upkeep of the Jesup Herbarium. The Eggleston collection amounted to over 15,000 specimens, among which were over 700 specimens of Crataegus (Hawthorn), a genus to which he had devoted many years of study, and in the identification of which he had became a recognized authority.

With the aid of Mr. Eggleston's contribution together with funds contributed by the College, Professor Chivers was able to secure material and technical assistance to begin the work of cleaning the dust and mold from the old mounted specimens, of repairing the damages suffered through the years of inadequately protected storage, and to initiate the task of preparing and mounting the unmounted specimens. Continuation of this task was greatly advanced during the decade of the 1930's by a grant of funds from the Federal Emergency Relief Administration which made it possible to hire student help. Later, student labor for this purpose was made available by a grant from the National Youth Administration. These two agencies, commonly referred to at the time as the F.E.R.A. and the N.Y.A., constituted a portion of the Federal Assistance efforts which were devised in the days of the depression. These grants, which amounted to a total of ?3,000, made it possible to continue the project until 1940. They were of inestimable value to the herbarium, and doubtless they were of great assistance to a number of students in that decade when funds for a college education were provided with great difficulty by many families.

In directing this work it was necessary for Professor Chivers to teach the students the required techniques and to watch that the work was performed with due care that specimens should be properly prepared and mounted, and that there should be no confusion of specimens and labels. After this part of the work was completed, the task of classifying the sheets for orderly filing required the professional knowledge of a trained botanist. To this task, and to the direction of the student projects, during the whole decade and for some years beyond, Professor Chivers devoted a large part of whatever time he could spare from his teaching and his departmental commitments. The time and effort involved are best measured by the fact that over 50,000 specimens were prepared, classified, and filed. That the Jesup Herbarium of today is a workable taxonomic collection is due almost entirely to his patient and accurate effort. Professor Chivers continued to serve as Curator of the herbarium until his retirement in 1950.

The Lyman Herbarium was named in honor of George Richard Lyman, Professor of Botany at Dartmouth from 1901 to 1915. It was organized in 1928, after Professor Lyman's death, when several of his former students and friends contributed funds to purchase his private herbarium. At the time it was installed at Dartmouth it included about 3,000 specimens. During the years since its purchase it has been increased to its present size largely by collections by some of the members of the Botany Department, particularly by Professor Chivers and by Professor Frederick S. Page, who has continued to add to it since his retirement in 1957. It is housed in the room with the Jesup Herbarium in steel cases outfitted with drawers adapted to contain the packets and boxes in which the specimens are filed. In addition to this material there are over 1500 specimens of ferns, conifers, and flowering plants from Professor Lyman's collection in the Jesup Herbarium.

In the years since the retirement of Professor Chivers the Jesup Herbarium has been increased in size by several accessions amounting to over 3600 specimens. Among these are some valuable foreign collections, one by Professor Carl L. Wilson of plants collected in Australia in 1957, one of plants from Japan received in exchange for duplicates from the Wilson Australian collection, and a collection from India received in exchange with the University of Delhi. Other important foreign collections are from Guatemala, Sweden, and Turkey.

Among the collections are several of interest to the Dartmouth Northern Studies program. These include Labrador plants from the McMillan-Bowdoin Expedition in 1934; plants from Greenland collected by David C. Nutt, Research Associate in Geography, during the Bartlett-Bowdoin Expeditions in the summers of 1940-43; plants from Ungava purchased in 1953; plants from the Coronation Gulf region in the North West Territories collected in the summer of 1955 by the late Dr. Ralph E. Miller of the Medical Faculty; a small collection from Cornwallis Island, North West Territories, by Ellsworth H. Wheeler of the Class of 1957; and plants from Alaska collected by Professor F. H. Bormann in 1953.

The Jesup Herbarium is used in a number of ways in both teaching and research. For both of these activities the specimens are available to illustrate the characteristics of various plants or groups of plants, to demonstrate the types of plants which inhabit certain environments or geographical regions, or for confirming the identification of new collections. To detail all its uses is beyond the purpose of this article. It should be emphasized, however, that neither the Jesup nor the Lyman herbaria are collections of plants in dead storage. They are in constant use by faculty and students in teaching and research, and research botanists from other institutions frequently consult them.

With adequate protection and proper care in handling, the specimens are practically imperishable. For this reason they furnish an interesting record of the periods and the places in which the older botanists have made their collections. I have no record of the oldest sheet in the Jesup Herbarium but I know that some date back to the 1820's. This historical interest plays no vital role in the use of the herbarium as a taxonomic tool, yet the collections dating back through the years may prove to be of great value in the newer, rapidly expanding field of experimental taxonomy. As the findings of the sciences of genetics and cytology have been applied by the taxonomist, the understanding of the species has changed from a concept of a rigidly fixed entity to one of a variable population, and with this basic change in philosophy, herbaria have acquired new and important values, for the old collections constitute a significant source of information for comparison with new collections.

For any herbarium to be of maximum utility it must be kept up-to-date. Although ]every plant has been assigned a Latin name, unfortunately these names are often subject to change. The reasons for this are valid but any explanation for them is beyond the scope of this article. This means, however, that someone must attempt to keep up with the literature of taxonomic botany in order to make the needed revisions. For the author of this paper this work, together with the preparation and accession of new collections, has been, a self-assigned project, and it has proved, to be an interesting and pleasant occupation for the years of retirement.

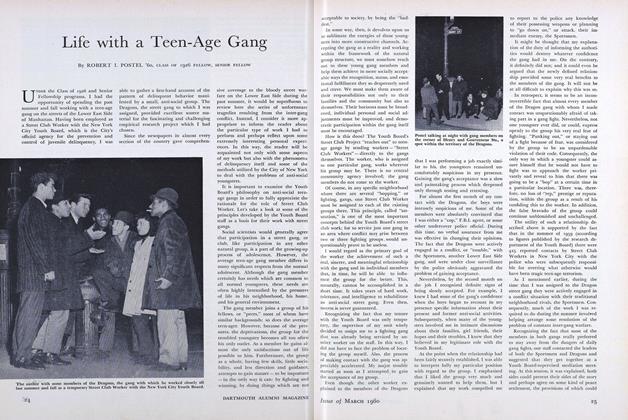

Professor Poole, author of this article, shown working with Jesup Herbarium specimens in Silsby Hall. Cases such as the one behind him contain over 55,000 catalogued specimens.

Henry Griswold Jesup taught botany at Dartmouth from 1876 to 1899 and was the first faculty member appointed in that subject.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFraternity Discrimination Faces a Deadline

March 1960 By THOMAS E. GREEN '60 -

Feature

FeatureAre Marriage and College Compatible?

March 1960 By MARGARET MEAD -

Feature

FeatureLife with a Teen-Age Gang

March 1960 By ROBERT I. POSTEL '60 -

Article

ArticleThe Mission of Liberal Learning

March 1960 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1960 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, ROBERT FISH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

March 1960 By RICHARD W. BALDWIN, IRA L. BERMAN

JAMES P. POOLE

Features

-

Feature

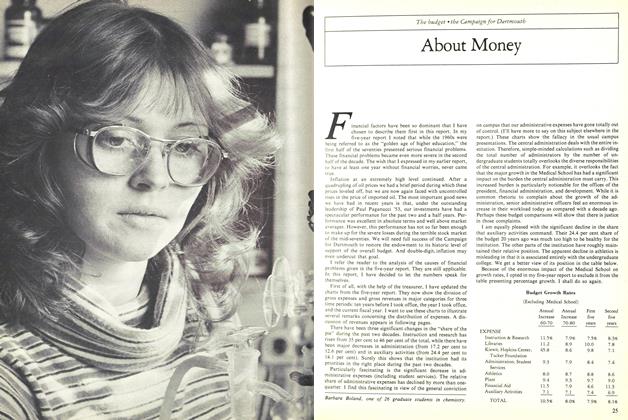

FeatureAbout Money

June 1980 -

Feature

FeatureModern Family

September | October 2013 By ALEC SCOTT ’89 -

Feature

Feature...AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

March 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

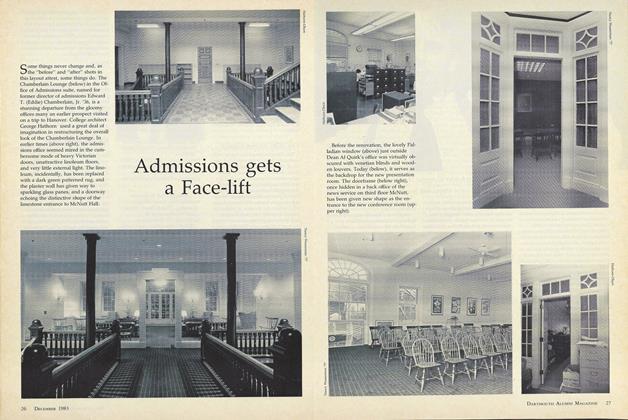

FeatureAdmissions gets a Face-lift

DECEMBER 1983 By Nancy Wasserman -

Feature

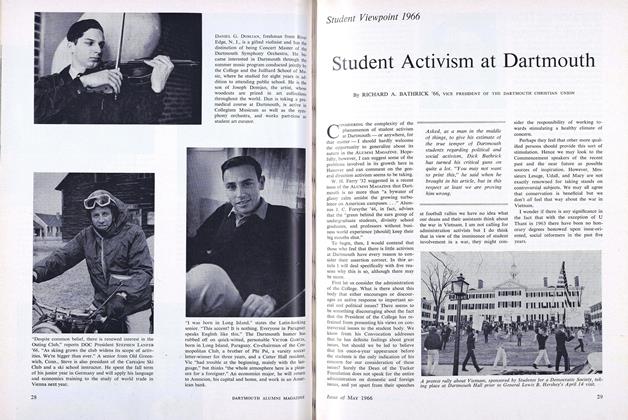

FeatureStudent Activism at Dartmouth

MAY 1966 By RICHARD A. BATHRICK '66 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2006 By Rodger Ewy '53, Rodger Ewy '53