Following is the text of the address delivered by President Dickey, January 22,at the formal dinner held in the Commonsin conjunction with the Hanover meetings of the Board of Trustees and theAlumni Council. The dinner celebratedthe successful completion of Dartmouth'sCapital Gifts Campaign, in which$17,574,794 was raised, and of the firstthird of the fifteen-year program leadingup to Dartmouth's bicentennial in 1969.

WE meet to celebrate an achievement. It is an achievement of which even as devoted a ship as that of Dartmouth can be proud without any great danger of falling prey to that false vanity which softens men and institutions when they mistake conspicuous good fortune for earned accomplishment.

So long as life remains, no achievement is ever the end of any truly significant human business. This is why commencements are the beginning rather than the end of education and, in a more pervasive sense, it is the truth caught and taught in the words of Robert Frost when he reminds us that the reward of daring is to be allowed to dare again.

We have glanced back tonight at some of the things that have been done during the past five years as all Dartmouth responded to the opportunity to use the final fifteen years of Dartmouth's second century as a period of sustained rededication to the pursuit of pre-eminence in the service of liberal learning, man's most civilizing enterprise.

As we pause at the third-of-the-way mark both to glance back over the course we've come and to gather ourselves for the task ahead, I am sure we and our effort will be the better for reminding ourselves of two things that often get lost to sight in the stress of great efforts.

First, let us never forget that every great effort stands on the shoulders of those who served the same cause earlier. The very possibility that our effort on behalf of Dartmouth can be significantly great is an inheritance of a past that was itself great in significance.

Secondly, as we prepare to move forward into the next stage of our effort, let us be clear in heart and mind that no effort, or fight, is ever more significant than the purpose that gives rise to it.

The purposes of liberal learning are not the contrivance of some agile intellect; they are fashioned out of the only thing man ever really created, namely, his own experience with life. It is out of his experience with life that man learned both his need and his capacity for liberating himself.

The liberal arts in their breadth and depth are at once both the story and the generating spirit of man's liberation from the meanness and the meagerness of mere existence. The testimony to this liberation is found in man's art, his literature and his way of living; these remnants of his experience bear witness to what he did, what he thought and how he felt as he strove, life by life, to make his lot more comfortable on earth and more meaningful in the universe of his expanding awareness. The human story is overlaid with the dust of spent time; our understanding of it at any particular moment will ever be partial, but that does not invalidate the story. The point is that man's experience with his own liberation is what he is all about. We can reduce but presumably never banish the infinite ignorance that stands between man and the ultimate Creator. But even if knowledge must always be finite and ignorance infinite, the tension of man's on-going struggle to be liberated is what holds the finite and the infinite together. That struggle is necessary to us because it is us. Without it we can only know we would be something less than human.

I make no apology for thus stating the mission of liberal learning in large terms. It is either man at his largest seeking to be larger or it is less than liberating.

The story of man's liberation from ignorance of the mind and the spirit has a majesty that we do well to acknowledge. At the same time, we also do well to remember that the primary work of education is not in celebrating the past, however glorious it may seem when smoothed out by that greatest of all levelers, time; the work of education must always face ahead to a rough, lumpy terrain simply because the human plight is packaged man by man and only thus can it be treated by education.

When we come down to cases in organized education we come to institutions as well as to individual men, and it is about Dartmouth as one of the historic American liberal arts colleges that I would speak briefly now.

Even though this is no time for wasting breath or softening our resolution with words of self-satisfaction, we are entitled to the confidence that goes with knowing that we go forward from a strong situation, that the critical fronts of the College are more strongly held than they were five years ago, that we see more clearly where we need to go and, perhaps above all, that we have it in us to mount and sustain the kind of total effort that brings reality to great aspirations.

There is no mystery about the foundation that must sustain any great enterprise of higher education. It has three parts: primarily, an institution-wide sense of adequate purpose; secondly, teachers who personify that learning which goes higher because it is both broad and deep, and which is education because it teaches the self to learn; thirdly, students who are able, ready and willing to work for a truly higher education. No edifice of educational pre-eminence can be erected if all these elements are not present and strong.

The next five years will test these elements of our strength as they have not been tested on an American college campus for a long time. It is not merely that we have set ourselves no little plans; nor is it entirely a matter of moving from plans into that stage of an undertaking where action becomes the great clarifier, the inescapable arbiter between being good and good enough. When we launched this effort we chose to submit ourselves to that kind of testing and I see no evidence that we will not be ready to meet such a judgment on even terms.

What worries me most now is that the terms by which we judge ourselves and will be judged cannot be remotely "even" in any previously predictable sense. The terms against which any educational effort will be judged five years from now, let alone in 1969, are rushing away from our reach on the astronomical scale of an expanding universe. The explosive, chain-reaction expansion of knowledge and the expanded range of potential human experience for millions of people, actually as well as vicariously, have reached a point and a pace where the very strategy, let alone the pedagogy, of traditional classroom teaching must be re-thought and re-fashioned if what is taught is to remain relevant to what is known, as well as what was known, let alone, what is yet to be known.

I have no new grand strategy to lay before you tonight. I do have a few convictions about, as the slang-phrase puts it, "which way is up" for us.

I suggest we must remain devoted to a sense of institutional as well as personal purpose. Specifically, I believe we must at least redouble our efforts to restore the relevancy of moral purpose as an essential companion of intellectual purpose and power in any learning that presumes to liberate a man from a lesser to a larger existence. There is simply no civilized alternative to having personal power answerable to conscience. Manifestly, this is not the end of the matter in a modern, complicated society of communities and governments, but let's not make the "impossible" unnecessarily difficult by confusing the end of the matter with the beginning. We are agreed it is not the end, but are we equally clear that the answerability of personal conscience is still a pretty fair starting point?

With the perspective of fifteen years on this job I am not, I assure you, suggesting that even liberal learning at its best can alone do the work of educating a neglected conscience. I am increasingly clear, however, that if liberal learning rejects the relevancy of this task to its concern for the whole of what a man may be, so too will it soon be rejected by the society where that learning has traditionally been the trusted beacon light of direction and significance in human values.

Many thing's are necessary to have and to hold teachers whose lives and work will exemplify liberal learning at its vigorous best. Here again, while compensation is not the end of the matter, it is not a bad place to start. It is in this spirit that I gladly tell you that the Dartmouth Trustees have accepted the challenge of enabling our top teacher-scholars to achieve an annual total income, including benefits. in the $25,000 range well prior to 1969.

The first decisive step on our way toward that goal will be an Alumni Fund that progressively exceeds one million dollars.

Finally a word about what is ahead for the student on whom all these efforts and these dollars are ultimately spent. What we want most is that he should want what is here. The strategy of ever-higher education - and that's just what any real higher education must be - will increasingly place on the student the responsibility for girding himself with the knowledge necessary to his learned capacity for thinking. The classroom, in all forms and sizes, must increasingly be primarily a point of stimulation to intellectual adventure rather than a pond - to borrow a fisherman's phrase - for catching stocked trout. And if the goal of Dartmouth's new educational program is to be ever more richly realized, the classroom itself, on the campus as in the follow-through of adult living and learning, must more and more be treated as the above-water portion of the iceberg beneath which there is a foundation of independent learning that is campus wide, all day deep and strong enough to bear the burden of our purposes and our praise.

It is the privilege of each one of us whose life is entwined in the destiny of Dartmouth, whether as beneficiary, worker or benefactor, to teach himself the truth that the foundation stones of this house of learning, as with those of any other great house, must be mended by each of us in his time and measure with both dollars and devotion.

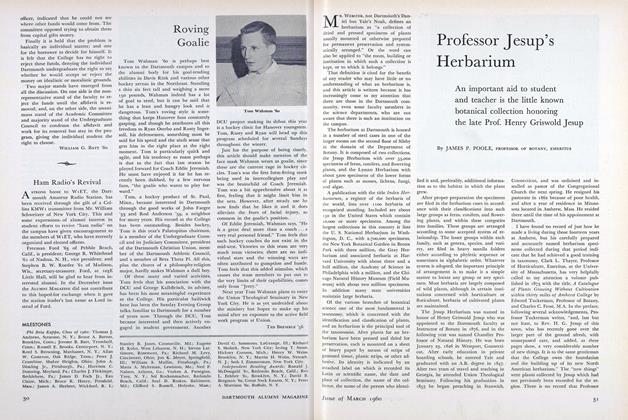

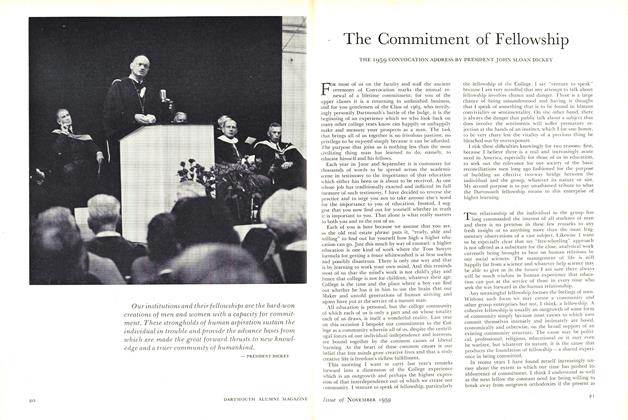

President Dickey speaking at the dinner of the Trustees and Alumni Council. The fifteen shields behind him symbolize the years of the program leading up to Dartmouth's bicentennial.

Chairman Charles J. Zimmerman '23 reveals the Capital Gifts Campaign total.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureProfessor Jesup's Herbarium

March 1960 By JAMES P. POOLE -

Feature

FeatureFraternity Discrimination Faces a Deadline

March 1960 By THOMAS E. GREEN '60 -

Feature

FeatureAre Marriage and College Compatible?

March 1960 By MARGARET MEAD -

Feature

FeatureLife with a Teen-Age Gang

March 1960 By ROBERT I. POSTEL '60 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1960 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, ROBERT FISH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

March 1960 By RICHARD W. BALDWIN, IRA L. BERMAN

PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY

-

Article

ArticleValedictory to 1953

July 1953 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Article

ArticleValedictory to 1954

July 1954 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Article

ArticleEducation: Creator of Centennials

October 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1961

July 1961 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1965

JULY 1965 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE OLDEST ALUMNUS

November, 1025 -

Article

Article1897 Secretary Illustrates His Point

March 1949 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Nominees, District II

May 1949 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah!

April 1954 -

Article

Article1977-1978 Bequest Program

October 1978 -

Article

Article'40 Rediscovers Dearie McGowen

FEBRUARY • 1988 By Dick Bowman '40