Many people cling to the odd notion that in this case the group somehow differs from the sum of its parts

THE POPULAR VIEW of you, an alumnus or alumna, is a puzzling thing. That the view is highly illogical seems only to add to its popularity. That its elements are highly contradictory seems to bother no one.

Here is the paradox:

Individually you, being an alumnus or alumna, are among the most respected and sought-after of beings. People expect of you (and usually get) leadership or intelligent followership. They appoint you to positions of trust in business and government and stake the nation's very survival on your school- and college-developed abilities.

If you enter politics, your educational pedigree is freely discussed and frequently boasted about, even in precincts where candidates once took pains to conceal any education beyond the sixth grade. In clubs, parent-teacher associations, churches, labor unions, you are considered to be the brains, the backbone, the eyes, the ears, and the neckbone—the latter to be stuck out, for alumni are expected to be intellectually adventurous as well as to exercise other attributes.

But put you in an alumni club, or back on campus for a reunion or homecoming, and the popular respect—yea, awe—turns to chuckles and ho-ho-ho. The esteemed individual, when bunched with other esteemed individuals, becomes in the popular image the subject of quips, a candidate for the funny papers. He is now imagined to be a person whose interests stray no farther than the degree of baldness achieved by his classmates, or the success in marriage and child-bearing achieved by her classmates, or the record run up last season by the alma mater's football or field-hockey team. He is addicted to funny hats decorated with his class numerals, she to daisy chainmaking and to recapturing the elusive delights of the junior-class hoop-roll.

If he should encounter his old professor of physics, he is supposedly careful to confine the conversation to reminiscences about the time Joe or Jane Wilkins, with spectacular results, tried to disprove the validity of Newton's third law. To ask the old gentleman about the implications of the latest research concerning anti-matter would be, it is supposed, a most serious breach of the Alumni Reunion Code.

Such a view of organized alumni activity might be dismissed as unworthy of note, but for one disturbing fact: among its most earnest adherents are a surprising number of alumni and alumnae themselves.

Permit us to lay the distorted image to rest, with the aid of the rites conducted by cartoonist Mark Kelley on the following pages. To do so will not necessitate burying the class banner or interring the reunion hat, nor is there a need to disband the homecoming day parade.

The simple truth is that the serious activities of organ- ized alumni far outweigh the frivolities—in about the same proportion as the average citizen's, or unorganized alumnus's, party-going activities are outweighed by his less festive pursuits.

Look, for example, at the activities of the organized alumni of a large and famous state university in the Midwest. The former students of this university are often pictured as football-mad. And there is no denying that, to many of them, there is no more pleasant way of spending an autumn Saturday than witnessing a victory by the home team.

But by far the great bulk of alumni energy on behalf of the old school is invested elsewhere:

Every year the alumni association sponsors a recognition dinner to honor outstanding students—those with a scholastic average of 3.5 (B+) or better. This has proved to be a most effective way of showing students that academic prowess is valued above all else by the institution and its alumni.

Every year the alumni give five "distinguished teaching awards"—grants of $1,000 each to professors selected by their peers for outstanding performance in the classroom.

An advisory board of alumni prominent in various fields meets regularly to consider the problems of the university: the quality of the course offerings, the caliber of the students, and a variety of other matters. They report directly to the university president, in confidence. Their work has been salutary. When the university's school of architecture lost its accreditation, for example, the efforts of the alumni advisers were invaluable in getting to the root of the trouble and recommending measures by which accreditation could be regained.

The efforts of alumni have resulted in the passage of urgently needed, but politically endangered, appropriations by the state legislature.

Some 3,000 of the university's alumni act each year as volunteer alumni-fund solicitors, making contacts with 30,000 of the university's former students.

Nor is this a particularly unusual list of alumni accomplishments. The work and thought expended by the alumni of hundreds of schools, colleges, and universities in behalf of their alma maters would make a glowing record, if ever it could be compiled. The alumni of one institution took it upon themselves to survey the federal income-tax laws, as they affected parents' ability to finance their children's education, and then, in a nationwide campaign, pressed for needed reforms. In a score of cities, the alumnae of a women's college annually sell tens of thousands of tulip bulbs for their alma mater's benefit; in eight years they have raised $80,000, not to mention hundreds of thousands of tulips. Other institutions' alumnae stage house and garden tours, organize used-book sales, sell flocked Christmas trees, sponsor theatrical benefits. Name a worthwhile activity and someone is probably doing it, for faculty salaries or building funds or student scholarships.

Drop in on a reunion or a local alumni-club meeting, and you may well find that the superficial programs of yore have been replaced by seminars, lectures, laboratory demonstrations, and even week-long short-courses. Visit the local high school during the season when the senior students are applying for admission to college—and trying to find their way through dozens of college catalogues each describing a campus paradise—and you will find alumni on hand to help the student counselors. Nor are they high-pressure salesmen for their own alma mater and disparagers of everybody else's. Often they can, and perform their highest service to prospective students by advising them to apply somewhere else.

THE ACHIEVEMENTS, in short, belie the popular image. And if no one else realizes this, or cares, one group should: the alumni and alumnae themselves. Too many of them may be shying away from a good thing because they think that being an "active" alumnus means wearing a funny hat.

Behind the fun of organized alumni activity—in clubs, at reunions—lies new seriousness nowadays, and a substantial record of service to American education.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe TPC Planning Program

April 1960 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Feature

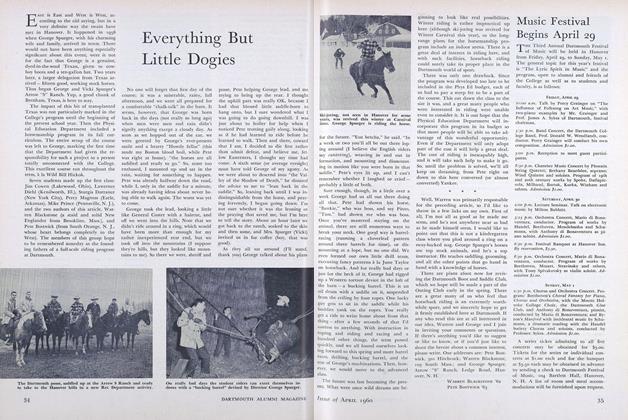

FeatureEverything But Little Dogies

April 1960 By WARREN BLACKSTONE '62, PETE BOSTWICK '63 -

Feature

FeatureTHE ALUMNUS/A

April 1960 -

Article

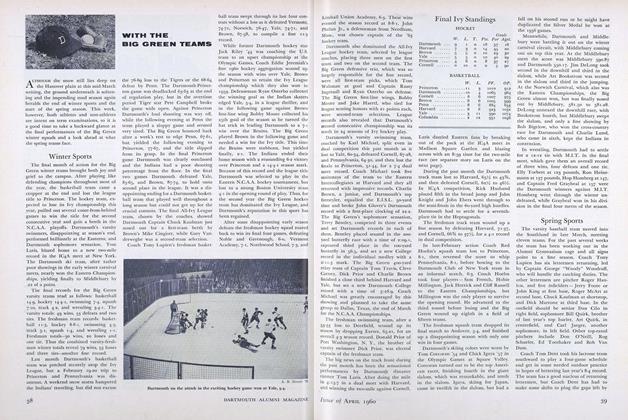

ArticleWinter Sports

April 1960 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

April 1960 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1951

April 1960 By LOYE W. MILLER, JAMES V. ROBINSON